#295 Cinderella Campaign revisited

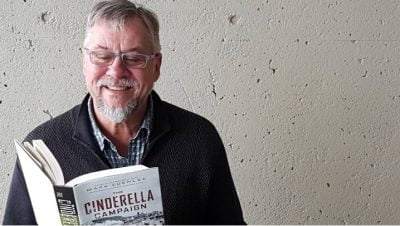

The Cinderella Campaign: First Canadian Army and the Battles for the Channel Ports

by Mark Zuehlke

Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2017

$37.95 / 9781771620895

Reviewed by Norm Fennema

First published April 30, 2018

*

Prolific historian Mark Zuehlke describes how battle-hardened but “woefully understrength” Canadian soldiers chased retreating Germans north towards the Seine River in The Cinderalla Campaign, reviewed by Norm Fennema.

Prolific historian Mark Zuehlke describes how battle-hardened but “woefully understrength” Canadian soldiers chased retreating Germans north towards the Seine River in The Cinderalla Campaign, reviewed by Norm Fennema.

Mark Zuehlke’s newest book on the Second World War reminds us that the story is as much about clashing egos as clashes with the enemy. Harry Crerar comes off particularly badly in this department; aged 56 when given command of the Canadian First Army, the Ontario-born veteran of the Great War already had an impressive military C.V. when his second war began.

Canadian historians associate him with the devastating last minute defence of Hong Kong, where green Canadian boys were sent to an outpost Churchill himself considered indefensible. Later, having led First Canadian Corps in the Italian campaign, Crerar was brought to England to lead the Canadians in the long-delayed invasion of France.

Here Zuehlke picks up the story, and gives us a portrait of a diminutive, insecure career soldier whose ego reminds us of what military historian (and notorious Holocaust denier) David Irving called The War Between the Generals (Congdon & Lattes, 1981), where command decisions are motivated by competition among army brass. Whatever the case, we’re reminded that in the Second World War, boys were losing their lives while generals focused on petty grievances – including, in Crerar’s case, jealousy bordering on obsession over a rival’s living quarters.

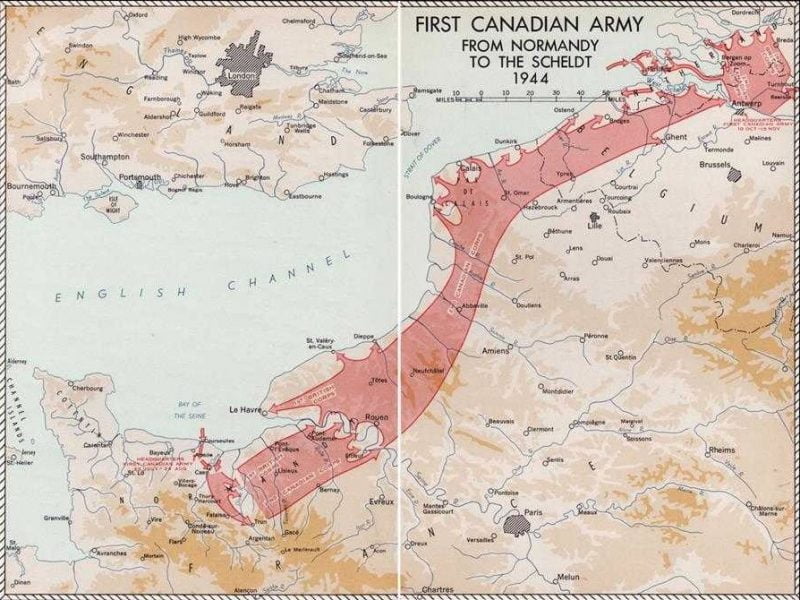

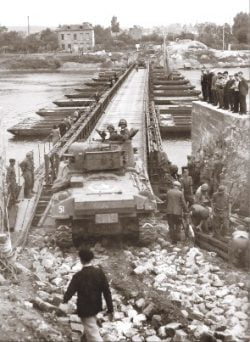

Divided into three sections, Zuehlke first dives headlong into an incredibly detailed accounting of the Canadians’ race north to the Seine River. Dropped into the battle two months after D-Day, we join the First Canadian army and its confusing array of divisions as the Falaise gap was closing on 100,000 trapped Germans. War weary and reduced in strength but battle hardened, the Canadians are tasked with chasing the retreating Germans north, clearing out pockets of resistance in the dozens of French towns.

As it turns out, the Canadians – and the Polish, British and Dutch forces under their command – faced far stiffer resistance, and losses, than Allied command had anticipated: based on losses in North Africa, the anticipated infantry casualty rate was woefully optimistic. Shortages from staggering casualties — up to 78 percent in one four day period in Normandy — were not easily solved (Zuehlke cites bureaucratic delays here), and consequently the First Army would “continue to march into battle woefully understrength.”

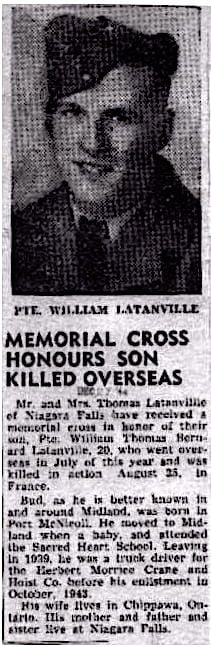

The heroic efforts that follow, each village yielding a potential episode for a Zuehlke version of a Band of Brothers mini series, are belied by the tragic waste of friendly fire and operational confusion of war. Zuehlke describes twenty year-old Private William Latanville and Private Charles Tait driven over and killed in their sleep in a pointless repositioning of their battalion’s vehicles. (Editor’s note: please see the message from Latanville’s grandson in the comments section below and the adjacent images). We read of five Canadian tanks disabled in turn by one 88 mm gun in an ill-conceived assault. Of six men needlessly killed in an already secured stand of trees by German land mines; of more by American bombers. A particularly bad day for the Calgary Highlanders occurred when the rare appearance of several Stuka bombers ended with 120 casualties.

Through the fog of war the author invites us into the continual weighing of acceptable losses when the overriding mandate was speed – and continual disappointment in amount of ground covered by day’s end. Tragedy was offset by the joy and relief of liberated civilians bedecking the Canadians with flowers and food and wine, helping them believe that “those boys left along the hedges, in the grain fields … might not have fallen in vain.”

But not everywhere: a regimental war diarist writes of a pro German French village where the Canadians received a colder reception than the Germans they captured.

From here we gain by fits and starts the broader picture: Montgomery’s preference for a combined Allied assault along the coast to free much-needed channel ports while enjoying overwhelming superiority in numbers, against Eisenhower’s divided, “broad front” strategy of supporting Patton’s thrust into Germany in tandem with the British-Canadian assault towards Antwerp. Monty lost because Eisenhower would not countenance the public opinion backlash if he “snatched the ball” from Patton’s 3th Army in what amounted to a “stunning football game” that was carrying Patton to glory. This is well known — though Zuehlke, better than most, depicts the attendant supply and manpower problems that fueled the Eisenhower/ Monty debate.

The book’s title explains its basic thrust. Cinderella Army, we learn, is a self-chosen moniker of the men of the First Canadian for the thankless and miserable work they were assigned while, in Zuehlke’s words, “its American and British cousins headed for glory with a bountiful supply of all that was required for the task.” And slog they did, getting over the Seine and capturing the well fortified ports of Dieppe, Bruges, Le Havre, Boulogne, and finally Calais.

With several chapters on Calais and the nearby Cap Gris Nez, we gain an exhaustive appreciation of this difficult assignment. The book ends here, with the White Cliffs of Dover now secure from German bombardment (the last of more than 1,000 German artillery bombardments killing five British civilians on September 29); Crerar lauding his men from his sick bed, and the Canadians marching to the next task: clearing the maze-like Scheldt estuary to open the port of Antwerp — what Monty called “the main business.”

Meanwhile, Montgomery’s planning had brought increasing attention to our Cinderella soldiers: with the planning and then failure of Operation Market Garden (A Bridge Too Far), conclusion of the war in 1944 became less likely, and the importance of the channel ports and their role in supplying the Allied armies more apparent.

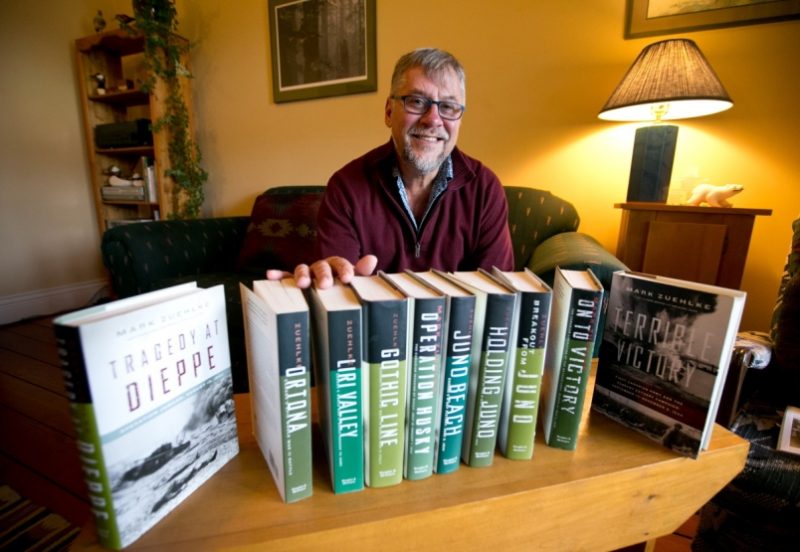

Thorough and incredibly well researched, Zuehlke weaves a multi-layered story that reflects the multiple primary sources he mines, including a heavy component of Canadian regimental war diarists, Canadian, British, and American military operational reports, the Crerar Papers, records of Bomber Command, and veterans’ interviews.

As one volume in the Canadian Battle Series, and the third by this author on Canadians in the Second World War, the writing will thrill the specialist even as it frustrates the general reader. Unlike the more accessible military history of the Stephen Ambrose-Citizen Soldiers (Simon & Schuster, 1997) genre, some foreknowledge of the events is assumed. The story here is an exhaustive day by day, hour by hour accounting, the first chapters filled with dozens of regimental names, platoons, companies, and military terms.

Familiarity with military language (recce troops, etc.), military hardware and organization is helpful (though there are helpful appendices), and a basic understanding of preceding events is critical to appreciate what the author has pulled together. Taken in chunks, with a search engine handy, the non-enthusiast may well learn more about the war here than from a university level course. Without that kind of commitment, the reader may want to begin with Chapter 6, before working back to that point, as it offers useful background context.

In the end, The Cinderella Campaign is an exhaustively detailed and important contribution to our understanding of the critical months of August and September of 1944; a narrow window that opens onto a wide historiography that includes allied strategy, inter-allied co-operation, allied combat effectiveness, the role of bomber command, individual heroism, troop morale, and much more.

*

Norm Fennema received his doctorate in Canadian history in 2003, with a field in American history. In 2007 he was happy to return with his wife and family to Vancouver Island, where he finds himself a continuing sessional lecturer, dividing his teaching between the History and Canadian Studies programs at UVic and working as an Open Learning Faculty member at Thompson Rivers University. Norm’s teaching load has included a heavy dose of World War Two courses, a lifetime area of interest informed by his parents’ experiences during the occupation of the Netherlands. Inspired by retired UVic scholar Brian Dippie, Norm enjoys teaching courses in North American history including religion, the twentieth century, the American West, Canadian social policy, the history of British Columbia, environmentalism, African American history, American history in film, the history of the automobile, and the history of sport. A recent member of the fifty plus cohort, he still runs – slower — and is learning to adjust to the reality that his adult offspring no longer need his advice.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#295 Cinderella Campaign revisited”

Mr. Fennema, my wife found this post while Googling my name. I’ve searched my name before (who hasn’t?!) and never had this come up in my search results, but I’m glad it did. My grandfather was Private William T.B. “Bud” Latanville. He died, as you know from reading this book, in August of 1944. That was 7 months before his only child, my father, William F. Latanville was born. Bud never knew he was going to be a father. My father never knew his dad. When I was born, in 1969, my parents decided to name me directly after Bud — I got all of his names: his first, middle two, and last names. Because my Dad was also “William” (Bill), they chose to give me Bud’s nickname, too. I have been William Thomas Bernard Latanville, “Bud” to all who know me, for 51 years, and this is the first time I’ve heard HOW Bud died. If my Grandmother, his widow, knew, she never told me, nor do I think she told my father. The death notice she received from the Canadian Government (I’ve seen it) didn’t mention HOW he died. I can’t say I’m happy to hear it was the result of an error, and a needless one at that. But it is good to know, finally, how it happened. Thanks for this review. I will be looking for a copy of Mark Zuehlke’s book.

Great to hear from you, Bud, with this poignant story of your grandfather’s tragic and accidental death. I’m delighted to put you in contact via email with Norm Fennema and Mark Zuehlke.

Wow, thanks so much for that William! Your story really brings it all home. And thanks for the documents as well. You will definitely get a lot out of Zuehlke’s book.

Comments are closed.