#264 From John McCrae to Morrison

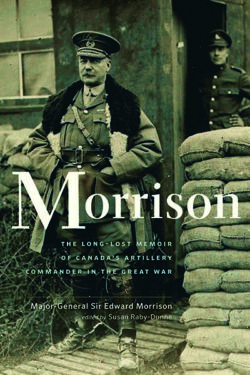

Morrison: The Long-lost Memoir of Canada’s Artillery Commander in the Great War. Major-General Sir Edward Morrison

by Susan Raby-Dunne (editor)

Victoria: Heritage House Publishing, 2017

$22.95 / 9781772032147

Reviewed by Michael Sasges

First published March 15, 2019

*

Edward Morrison was one of no more than fifty general officers who directed Canadian Corps battlefield activities in the Great War under either Julian Byng, the Briton who was the corps’ first General Officer Commanding (GOC), or Arthur Currie, the Canadian who was its second, and last, GOC.

Edward Morrison was one of no more than fifty general officers who directed Canadian Corps battlefield activities in the Great War under either Julian Byng, the Briton who was the corps’ first General Officer Commanding (GOC), or Arthur Currie, the Canadian who was its second, and last, GOC.

Morrison: The Long-lost Memoir of Canada’s Artillery Commander in the Great War is also a rarity. The memoirs of only one other Canadian Corps general officer have been published. These figures are drawn from an article published fifteen years ago by Patrick Brennan, “Byng’s and Currie’s Commanders: A Still Untold Story of the Canadian Corps.”[1]

The number of first-hand memoirs might have changed in the last few years owing to the flood of publications marking the Great War centenary, but surely not enough to deny the preciousness of this book and its unsung author.

Edward Whipple Bancroft Morrison (1867-1925) was a London, Ont. native. He was a newspaperman and militiaman who joined the Army, then called the Permanent Force, in 1913 as director of artillery. The Great War was his second war; he had also served in the Boer (South African) War.

In South Africa, Morrison and another Canadian artillery officer, John McCrae, either started or continued a friendship. They went to war together in 1914, Morrison as commander of a brigade of artillery and McCrae as his brigade major, or chief administrative officer. Morrison (and Currie) stood with Bonfire, McCrae’s horse, at the physician-poet’s funeral in 1918.

Susan Raby-Dunne, the editor of Morrison, is also McCrae’s biographer (John McCrae: Beyond Flanders Fields, Heritage House, 2016). “The more I learned about Morrison and the Great War, the more astonished I became that he was relatively unknown by anyone other than some artillery personnel, a few war historians, and the most avid military history buffs,” Raby-Dunne writes in her introduction.

She eventually learned that the grandchildren of Morrison’s wife possessed a “300-page typewritten memoir-in-progress” that she received permission to prepare for publication with the assistance of interested military officers.

Morrison is a terrific read because it advances multiple understandings and appreciations of personhood and nationhood.

For example, the 1917 that the author remembers and recreates here is the year Canadians, symbolically, closed out their country’s nineteenth century and opened up its twentieth. In that year the Canadian Corps captured three pieces of elevated countryside in France and Belgium, Vimy Ridge in the spring, Hill 70 in the summer, and Passchendaele Ridge in the fall.

At two of the three, Vimy and Passchendaele, they seized countryside the Germans had denied other Allied armies. Morrison, as GOC, Royal Artillery, Canadian Corps from December 1916 to May 1919, commanded the artillery contribution to the success of all three assaults.

Meanwhile, on the domestic front, in the 1917 election women (mainly nurses) serving in the armed forces received the federal franchise. Worried about this development, Morrison thought they might vote to end Canada’s participation in the war by voting against Prime Minster Borden’s conscription program. This was a wrong appreciation: they voted for Borden and conscription, which contributed a momentous quality to the extension of the franchise, which was extended federally to Canadian women in 1919.

Morrison’s frequent demonstrations of the courage and fortitude of the “Other Ranks” provide important social commentary in The Long-lost Memoir – and an important corrective to his wrongheaded view of the franchise extension in 1917.

A Sunday morning trip up one of two roads under construction before the Passchendaele assault produced this expression of admiration from Morrison:

I had never had a higher respect for the pioneers than I did for those troops working on the road. They had absolutely no cover, not a shelter, trench or dugout to go to, no matter how heavy the shelling became, but they worked steadily on with their officers sauntering up and down the road, and there was not even the possibility of getting an ambulance to them to pick up the wounded.

At Vimy and Passchendaele, the Germans in their high position daily shelled the Canadians below as they prepared for the assaults. Morrison witnessed this. “Through the smoke we saw them scattering across country out of the danger zone,” he wrote. A halted column of transports, mules, and trucks was also shelled in his presence. “Six men who were immediately beside me were killed or wounded.”

In such scenes are the “blood and mud” origins, once more, of Dominion government allowances for the wives and children of soldiers and pensions for the widows and orphans of dead soldiers and lifelong medical care for the wounded and pensions for the permanently disabled.

Morrison’s memories of alliance difficulties unearth the battlefield-autonomy roots of the pursuit of Canadian leaders, after the Great War, of an international presence for Canada independent of the British Empire.

Before Hill 70, his first battle as Canadian Corps General Officer Commanding, Arthur Currie had to “battle” a British high command preference for an assault elsewhere. Morrison provided artillery intelligence and concerns that won Currie the day. Below Hill 70, the “rolling ground” and industrialized villages offered what Morrison termed “cover for batteries and observation of the enemy’s position.”

At the preferred British target, equivalent cover did not exist. Before Passchendaele, artillery considerations again forced Currie to stand up for Canada. The commander of the 1st British Army’s artillery refused to approve part of the artillery scheme Morrison prepared for the assault, “and made it almost a personal matter.” Remembers Morrison:

At my request the Corps Commander strongly recommended to the Army Commander that the Canadian Corps Artillery should be allowed to adopt its own methods, which had proved so successful … and he finally secured immunity for us from interference. This is worth noting in view of the slow progress on the northern front, in the months just proceeding, notwithstanding the immense force of artillery [that] should have been sufficient to blast away all opposition to the Infantry.

A general officer’s war is not a private soldier’s war. Immediate circumstances are different; challenges and their resolution are different; staying alive or whole is less likely and more likely; keeping dry and warm is more difficult and less difficult. Edward Morrison appreciated the differences, and honoured them.

*

A retired Vancouver newspaper editor and reporter, Mike Sasges notes that the only other book by a Canadian Great War gunner that he has read is Harold Innis’s The Fur Trade in Canada (1930). For The Ormsby Review Mike has written two essays, “From Quilchena Creek to Flanders” (#39, November 7th, 2016) and “Grappling with Indian Apples (#124, April 25th, 2017). Mike Sasges has an MA in Graduate Liberal Studies at Simon Fraser University. He lives in Merritt.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] See Patrick H. Brennan, (2002) “Byng’s and Currie’s Commanders: A Still Untold Story of the Canadian Corps,” Canadian Military History 11:2 (2002).

Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh/vol11/iss2/2