#262 Lillooet pithouses revisited

The Last House at Bridge River: The Archaeology of an Aboriginal Household in British Columbia During the Fur Trade Period

by Anna Marie Prentiss (editor)

Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2017

$59.00 (U.S) / 9781607815433

Reviewed by Bob Muckle

First published March 9, 2018

*

Editor’s note: While the coastal Indigenous people of British Columbia lived in longhouses made of cedar slabs or boards, residents of the Interior devised traditional semi-subterranean winter dwellings known as pithouses or kekulis.

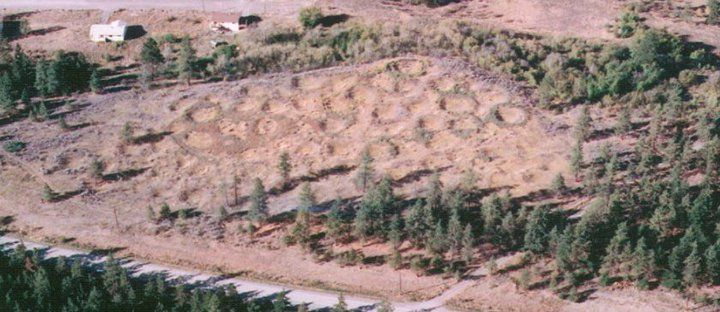

Archaeologists have excavated two major pithouse village sites in the territory of the St’át’imc (Lillooet) Nation: Keatley Creek and Bridge River.

The Bridge River Site is in the territory of the Xwísten First Nation (Bridge River Indian Band), whose name for pithouses is s7ístken in the Interior Salish language.

Containing 80 identified s7ístken, the Bridge River site has been excavated by archaeologists from the University of Montana led by Anna Marie Prentiss, whose Ph.D is from Simon Fraser University.

Reviewer Bob Muckle welcomes Prentiss’s The Last House at Bridge River: The Archaeology of an Aboriginal Household in British Columbia During the Fur Trade Period as “the only comprehensive archaeological investigation of a historic period occupation of a pithouse in the mid-Fraser River region.”

Xwísten First Nation have recently built a replica of a s7ístken which, along with the Bridge River site itself, is open for public visits. – Richard Mackie

*

Considerable archaeological research has been undertaken in recent decades at large prehistoric village sites in the mid-Fraser River region of British Columbia. These villages consist primarily of semi-subterranean homes, usually with a circular depression dug into the ground that serves as the floor and the base for a wooden structure supporting a roof covered with earth.

Considerable archaeological research has been undertaken in recent decades at large prehistoric village sites in the mid-Fraser River region of British Columbia. These villages consist primarily of semi-subterranean homes, usually with a circular depression dug into the ground that serves as the floor and the base for a wooden structure supporting a roof covered with earth.

There are various names for these kinds of homes, with those First Nations associated with them usually having a name in their own language. Archaeologists typically refer to them as pithouses. Once abandoned, the roofs collapse and all that remains visible is the large depression that served as its base, partly in-filled with roof debris. Archaeologists call these depressions housepits.

The Bridge River site, near Lillooet, is one of the largest of such villages in the province, with eighty documented housepits. Anna Marie Prentiss’s edited collection, The Last House at Bridge River: The Archaeology of an Aboriginal Household in British Columbia During the Fur Trade Period, a collection of essays edited by Prentiss of the University of Montana, focuses on the most recent occupation level in one of these housepits — Housepit 54.

The Last House at Bridge River provides the only comprehensive archaeological investigation of a historic period occupation of a pithouse in the mid-Fraser River region.

Investigations at Housepit 54 add to our understanding of Indigenous peoples and cultures in the mid-Fraser region in the early and mid nineteenth century, support oral history accounts, and provide new data and insights. The particular focus of Prentiss’s analysis is the era between the 1830s to the 1850s, immediately prior the Fraser River gold rush.

Most of what is known about life in these pithouses in the late prehistoric and early historic period has come from Indigenous oral history, including recollections or stories passed to anthropologists in the late 1800s and early 1900s, long after the houses had been abandoned.

Anna Marie Prentiss reveals that Housepit 54 had been used for at least 1,000 years before the final occupation, and that in this period the house may have been inhabited by two extended families.

Prentiss, who has a long history of doing archaeology in the mid-Fraser region, brought together the book’s 24 contributors and coordinated its thirteen chapters. She is also the sole author of three chapters, including the Introduction and Conclusions, as well as a co-author of four others.

At 267 pages, The Last House at Bridge River has the high production values of a scholarly monograph. It is well illustrated with 107 figures, 31 tables, and an extensive list of references for each chapter. The figures include multiple maps, graphs, sketches, and photos. They are black and white, but of high quality and well-chosen. The tables are also well chosen, providing key data without the need to resort to appendices.

The first three chapters situate the Bridge River Archaeology Project. Chapter 1 provides describes the location of the site, the dimensions of Housepit 54 (it is about thirteen metres in diameter), and a thorough overview of relevant archaeological and ethnological work in the region.

Chapter 2 provides overviews of the environment, prehistoric Indigenous resource use, and the impacts of Euro-Canadians on Indigenous peoples. The archaeological background is provided in Chapter 3, including an outline the history of the Bridge River Archaeology Project, which is a collaborative effort between the University of Montana and the Bridge River Band (also known as the Xwísten Nation). This chapter also summarizes earlier work at the site, explains that the focus on Housepit 54 is the third phase of this long-term project, and provides an overview of excavations, stratigraphy, dating, and features of the housepit.

The following five chapters focus on descriptions and discussions of material recovered from excavations: chapters 4 and 5 focus on lithics (stone tools), providing evidence that lithic technology remained an essential part of the culture for the household during this final occupation; Chapter 6 describes the historic period artifacts that form part of the assemblage, including glass beads, metal arrowheads, a metal finger ring, and a horseshoe; chapters 7 and 8 concern animal and plant remains.

Bones recovered include those of salmon and deer for food and those of coyote and weasel, presumably harvested for pelts. Bone artifacts include those used in woodworking and hide preparation. Food plants, identified by pollen analysis, include Saskatoon berries and another taxon suggested to be elderberry. Several other kinds of plants were presumably used for technological purposes such as manufacturing baskets, lining pits, insulating the roof, and covering the floor.

The next three chapters concern spatial analyses. Chapters 9 and 10 focus on standard scientifically oriented spatial analysis, which indicate designated activity areas within the house and suggest an egalitarian household strategy. Chapter 11 focuses on spatial analysis using an Indigenous framework, using cultural categories informed by local First Nations, and taking into account age, gender, and situation.

Chapter 12 concentrates on cultural change between the late pre-colonial and early colonial periods in the Bridge River area, comparing the nineteenth-century occupation layer of Housepit 54 with a late pre-colonial occupation revealed by a pithouse excavation in a village a few km away.

Chapter 13 summarizes key findings, outlines the significance of the investigations, and reflects on theory – that is, on the analytical frameworks that inform the study. This includes the insight that the occupants “sought to maintain a highly traditional existence, yet they were fully aware of the challenges and opportunities emerging in the world around them” (p. 253). The project was not guided by a single theoretical paradigm but common themes emerged including Indigenous agency and persistence.

I like several things about this book. It is a useful contribution to understanding processes of change in nineteenth century British Columbia, especially in the mid-Fraser River region. It significantly expands the scope of historic period archaeology in the province by focusing on First Nations, who have received scant previous attention. The book also provides a useful model for incorporating Indigenous frameworks into archaeological analyses and offers interesting data and insights for comparison.

I have few, and only minor, criticisms. I wish the book didn’t have the word “Aboriginal” in the title. While favoured by provincial and federal governments in the past, it was never fully adopted by First Nations peoples themselves and began to go out of use some years ago. In my view, a preferable word choice would have included “First Nation” or “Indigenous.”

I also wanted to know more about the archaeologists’ collaboration with the Bridge River Band (Xwísten). The book also lacked more explicit consideration of how the investigations extend the scope of historic archaeology in the province.

The book should find its way on the bookshelves of many people with an interest in B.C. archaeology, history, and First Nations. The primary readership is likely to include archaeologists, especially those with interests in the southern interior regions of the province, but others are sure to find value in the book as well, including those more broadly curious about both Indigenous culture and settler history.

With its scholarly apparatus – its methodological and theoretical context and considerable data — the book is clearly aimed at academics. But this doesn’t necessarily mean it will not find a larger readership. Its accessible style means that non-specialist readers of B.C. archaeology, history, and First Nations will deepen their knowledge of an Indigenous household and village site during British Columbia’s fur trade period in the southern interior.

*

Robert Muckle teaches archaeology and anthropology at Capilano University in North Vancouver, and is currently writing a book on a historic period archaeology project he has directed in the Seymour Valley. Previous books include Introducing Archaeology, 2nd edition (University of Toronto Press, 2014), The First Nations of British Columbia, 3rd edition (UBC Press, 2014), and The Indigenous Peoples of North America (UTP, 2012). He has also co-authored (with Laura Gonzalez) Through the Lens of Anthropology: An Introduction to Human Evolution and Culture (UTP, 2016).

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#262 Lillooet pithouses revisited”

This review is fascinating. I am looking forward to studying this book more.

Comments are closed.