#248 Kaho’olawe; 8th Hawaiian island

Journey to Kaho’olawe

by Hans Winkler and Cease Wyss (T’uy’t’tanat)

Vancouver: Grunt Gallery, 2017

$20.00 / 9781988708027

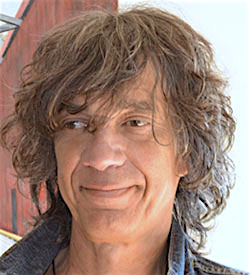

Reviewed by Chris Arnett

First published Feb. 13, 2018

*

Stories of BC-Hawaiian connections have a certain allure to those of us in the temperate rainforest in that by some past association we may have something in common – and it’s certainly not the weather.

The Gulf Islands Driftwood, Salt Spring Island’s community newspaper, once boasted on its masthead that it was published on “Canada’s Hawaiian Islands.” Wishful thinking, perhaps, but Native Hawaiian men — former employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) known as Kanakas and Sandwich Islanders — did settle on the island in the 1870s and some descendants remain, proud of their heritage, on Salt Spring. Other Kanakas found work in the gold rush, when Kanaka Bar was named, and in the early sawmills of Burrard Inlet, and settled on the mainland.

This is all because the HBC had opened a commercial agency in Honolulu in 1833 as an entrepot point between the North West Coast of North America and Chinese and larger Pacific markets.

Barreled salmon, sawn lumber, potatoes, and flour went one way, while rice, salt, sugar, molasses, tobacco — and Kanaka sailors and labourers — went the other.

Salt Spring Islander Tom Koppel, in Kanaka: The Untold Story of Hawaiian Pioneers in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Whitecap, 1995), and Jean Barman, in Maria Mahoi of the Islands (New Star, 2004), have added substantially to our awareness of the Hawaiian connection.

The latest contribution to this historiography is a slim, illustrated book Journey to Kaho’olawe based on a five-day multi-media performance /presentation at the Grunt Gallery, Vancouver, in May 2017.

The book and the exhibition juxtapose the social memory of Coast Salish people of Hawaiian ancestry and their return to Hawaii with the struggle by Hawaiian people to return to Kaho’olawe, the smallest of the eight main volcanic Hawaiian Islands and a place long used, and abused, by the US military as a bombing range.

The project was realized by Squamish media artist Cease Wyss (T’uy’t’tanat) and German conceptual artist Hans Winkler, who document in text and images their experience with Kaho’olawe each by way of their distinct backgrounds.

An introduction by Vancouver-based curator Glenn Alteen and a concluding chapter by Jean Barman and Bruce McIntyre Watson frame the work in its historical and colonial context.

Winkler, fascinated by the island and its history, became involved with Hawaiian people in the long process of reclamation and restoration of Kaho’olawe after years of environmental abuse. Through activism, four photo essays, and photography, Winkler probes the subject via different levels of awareness, citing the indifference of newcomers to the island’s rich heritage, their impact on the sensitive island ecosystem — beginning with the introduction of goats by none other than Captain Vancouver — subsequent cattle and sheep raising, and the accumulative destructive impact on a sensitive ecology.

With the advent of the Second World War, the island was appropriated by the US military and used as a bombing range for the next fifty years. During the Vietnam War, some 2,500 tons of bombs were dropped on the landscape, and in 1965 simulated atomic explosions using 500 tons of TNT cracked the island’s aquifer, turning it into a lifeless saltwater pond.

Once known as a place of great spiritual power, Kaho’olawe became “the most bombed island in the Pacific” (p. 16). In the 1970s the Project Kaho’olawe Ohana (PKO) began occupying the island to halt the bombing. After a protracted legal battle, the bombing ceased and Hawaiian people were once again allowed to access the place.

While Winkler situates the story in its colonial context he then moves into more abstract interpretative forays drawing on early twentieth century Russian Kazimar Malevich’s use of “square” iconography to conceive of the “disappearance of culture and art” (p. 27).

A series of outlined and filled-in square “blanks” (and a white silhouette of the island on black) evoke for Winkler “the symbolic cartographic disappearance of the island” (pp. 26, 30-31); and concomitant concepts of “blank space,” “vanishing art and culture,” “cosmos and silence,” “death,” and whatever else arises when thinking about the island, leave us with rhetorical questions such as “Has not the blank itself become the most consequent of all artistic practices?” and “Does not the very act of vanishing eventually become itself a form of art?” (p. 27).

One can suppose, but Winkler’s other images of bomb craters, landscapes, street references to Hawaiian sovereignty, and the people returning to the island have more resonance.

Things begin to lose focus somewhat in the last essay “Navigation, Cupstones and Tatoos,” with photographs of Hawaiian petroglyphs and tattooed Polynesians from various cultures around the Pacific.

Winkler is clearly attracted to the material culture of the island, and mentions the thousands of archaeological sites and artifacts, yet he muses on similar patterns elsewhere in the world as a means to emphasize the significance of the island.

His offhand statements about the rock art — “They show a remarkable connection to ancient cultures from around the world” (p. 40) — given without explanation, unfortunately dredge up Western notions of diffusionism to account for something Kaho’olawe doesn’t need, given its demonstrable agency.

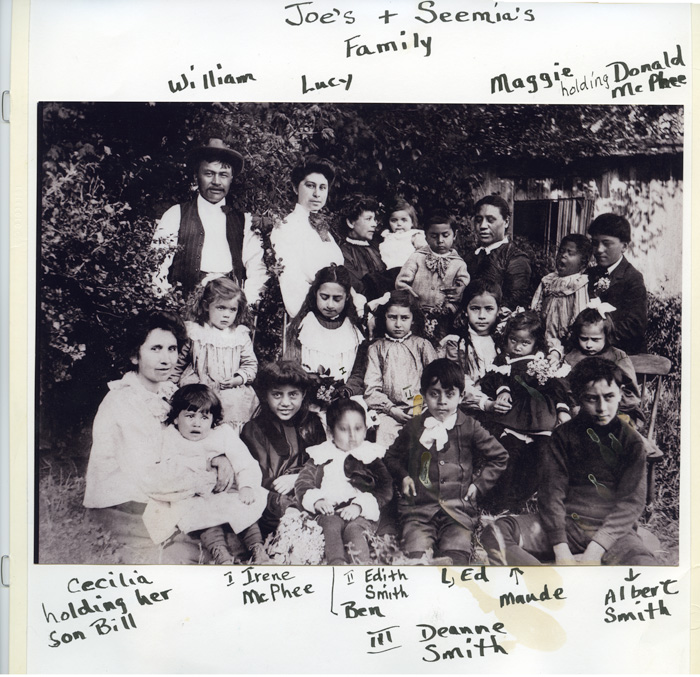

Cease Wyss, as a descendant of a male HBC employee and a Coast Salish woman, situates her contribution in her genealogy, and thus her journey is a very personal one.

This is most evident in her contribution, a family history and a 38-page collection of colourful genealogical charts, family, places, and animals, not unlike a precious family scrapbook with memories pertinent to her identity, be it Hawaiian or Squamish.

In “Leaving Paradise,” the concluding chapter, historians Barman and Watson ground this early twenty-first century oral history and art show in the context of Hawaiian colonial history and the late eighteenth and early twentieth century fur trade of the North West Coast.

Surprisingly–contrasting the contribution of Cease Wyss–Barman and Watson conclude that relationships between Hawaiian men and native women were not successful despite a common Indigeneity. “While many Hawaiian men cohabited with Indian women they did not become Indians,” they assert (p. 11), despite the fact that many of their children identified as Indigenous and that their descendants certainly did.

Indeed, the most powerful native leader in Victoria in the 1850s was Chee-al-thluc (King Freezy) of the Songhees, the son of a Kanaka and a high-ranking woman.[1]

Barman and Watson seem unaware that Hawaiian men and their offspring integrated into Indigenous societies if circumstances warranted, which is why many among the Squamish, Hul’qumi’num, and Saanich people have Hawaiian ancestry.

I was reminded that — with similar histories of colonization, land alienation, and loss of income (resources) — people from different Indigenous communities around the world have a lot in common.

Of all the contributions to Journey to Kaho’olawe, Cease Wyss’s multi-layered series of text and imagery is both a personal view and a universal one. Not often do Indigenous people share Indigeneity with places other than their traditional homes. It is in this context that Journey to Kaho’lawe is, as she puts it, “a powerful interwoven story of reclamation” (p. 65).

*

Chris Arnett is an author, artist, archaeologist, musician, historian, and heritage consultant who lives on Salt Spring Island and in the Vancouver area, where he is currently a sessional instructor in the Department of Anthropology at UBC. His parents, grandparents, and great grandparents instilled in him a keen interest in North American history and in the people and culture of his ancestral homelands of New Zealand, Cornwall, and Norway. He continues his ongoing self-directed and institutional ethnographic, archaeological, and sometimes musical research in British Columbia. With Annie York and Richard Daly, Chris wrote They Write their Dreams on the Rock Forever: Rock Writings in the Stein River Valley of British Columbia (Talonbooks: 1993). He also wrote The Terror of the Coast: Land Alienation and Colonial War on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, 1849-1863 (Talonbooks: 1999), and he edited Beryl Cryer, Two Houses Half-Buried in Sand: Oral Traditions of the Hul’q’umi’num’ Coast Salish of Kuper Island and Vancouver Island (Talonbooks: 2008).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] For Chee-al-thluc see Grant Keddie, Songhees Pictorial: A History of the Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790-1912 (Victoria: Royal BC Museum, 2003).

Comments are closed.