#204 Climbing bard of Maurelle Island

At Home in Nature: A Life of Unknown Mountains and Deep Wilderness

by Rob Wood

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2017

$22.00 / 9781771602518

Reviewed by John Gellard

First published November 20, 2017

*

Rob Wood might have saved my life … or at least my left foot.

Rob Wood might have saved my life … or at least my left foot.

Some years ago I fell off a log bridge into Cottonwood Creek in the wildest part of the Stein valley. I broke my leg. I was alone. I swore desperately and dragged myself and my pack up onto the bank. Surely time to panic.

“If you are ever in a seemingly impossible situation in the wilderness, stop and make a cup of tea. If you can do this, you know you’re going to be all right.”

Rob Wood had said that to my Grade 8 students in 1984 on an excursion in Strathcona Park, a place he has protected by helping get rid of mining.

Must make a brew, then. What else was there to do? Focus. Drag out camp stove. Light it. Boil water. Put in a tea bag. I sat back, sipped my tea and calmly assessed my hopeless situation.

That moment of “mindfulness,” of living in the present, settled me down for my long wait. I was discovered and rescued five days later.

“Mindfulness,” being “In the Zone,” knowing that we are part of nature like whirlpools in the rip tide of “universal consciousness” are central themes in At Home in Nature.

*

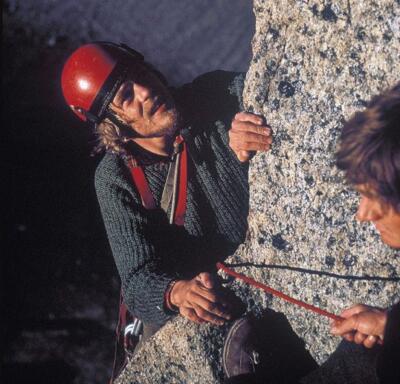

Rob Wood leaves the metaphysical discussion to the end. First he pays his dues by taking the reader on some extreme adventures. It’s a story of a life lived to the fullest, from rock climbing on the crags of his native Yorkshire, to studying architecture in London, to mountaineering and ice-climbing in the Arctic and the Rockies, to starting an off-the-grid co-op, to creating a magnificent homestead on Maurelle Island.

There’s a compelling structure to the book. It’s rather like a long and detailed “Proust Questionnaire” — 38 questions beginning with “What made you choose to leave the old country and come to Canada?” probing ever more deeply into breathtaking adventures, and ending with “What exactly is ‘universal consciousness?’” asked by a party of young skiers at Rob’s sixtieth birthday celebration.

The group had struggled through a blizzard to find a tiny cabin buried in deep snow 4,000 feet above Bute Inlet. They find the cabin, dig themselves down to it, light the wood stove, unpack the cobbler, and make a brew.

Then it’s story time.

*

The reader is swept along by the forces that propelled Rob and his comrades on their quest for “the freedom to detach ourselves from society’s umbilical cord” and establish a relationship with nature. The quest guides him from the Yorkshire crags, “pushing internal and external limits” through to an “outer island” in the storm-tossed rip tides on the outer edge of the Salish Sea on B.C.’s West Coast.

Let’s visit a couple of the adventures along the way.

With Mick Burke, he climbs the Nose of Yosemite’s El Capitan in 1968. It took five days of supreme psychological and physical effort in the sweltering heat to scale the 3,000-foot granite wall. That feat inspired others to complete a climb that seemed impossible. By the way, just recently a climber was killed when a giant slab of granite fell off El Capitan.

Rob and his friend, the famous British climber Doug Scott, rope their way up Mount Waddington, the “Mystery Mountain,” forty miles up the Homathko River beyond the head of Bute Inlet (“Canada’s Grand Canyon, only better”), with its unpredictable violent freezing katabatic winds and snow squalls. Rob’s wife Laurie and friends wait overnight at the base camp with “brew.”

The homesteading idea arises in its own good time. “My woolly-headed idealism seized the moment to ask ‘why don’t we quit our jobs in the city and find ways to live permanently somewhere out in the wilds?’”

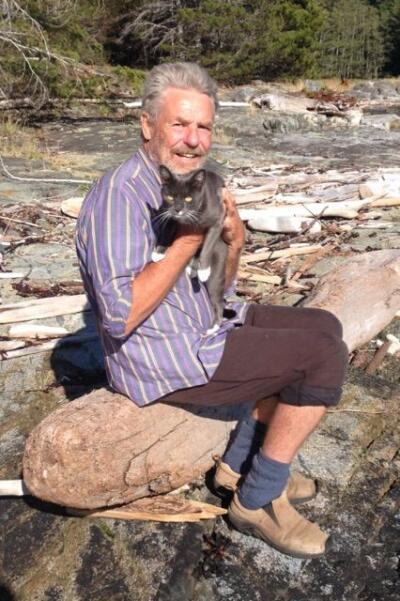

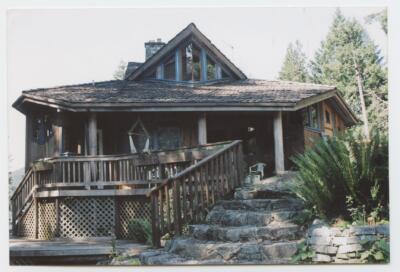

And so the mountaineers, including Laurie’s daughter Kiersten and a founding member of Greenpeace, buy a 160-acre clear-cut on the south shore of Maurelle Island. Ten families move there and live “off the grid,” helping each other build “cosmic shacks” and make gardens. They acquire animals — chickens, pigs, and a horse. Rob builds a sturdy catamaran needed for trips up and down stormy and tide-ripped Hoskyn Channel to Heriot Bay on Quadra, their access to the wider world. The “free range” children grow up fearless and resourceful. Kiersten finds a way to get the horse onto the catamaran. They do remarkably well in the community school, a short boat ride from Maurelle.

Some of the families move away over the years, but Rob and Laurie remain. They build a magnificently “organic” house — granite fireplace and all, generate their own hydroelectricity, and create a computer-irrigated garden that produces sixty percent of their food, with a surplus to sell in town.

Rob gets as much off-island work as he needs – carpentry and wilderness guiding, and runs a designing business from home. Their “community” is a loosely knit assortment of “boat people” who help each other through various ordeals, like being stuck in a snowstorm.

A few remarkable characters stand out. There’s Kayak Bill (Billy the Bolt) who travels the B.C. coast living on the land and the sea.

There’s Dean Potter, who jumped off the 9200-foot summit of Mount Bute in a wing suit, making a three-minute flight into the valley. Rob guided the filmmakers up Bute Inlet and the Homathko valley, and helped rig Dean’s launching platform.

To go through the air like a flying squirrel would of course require the ultimate of the “mindfulness” that informs Rob Wood’s guiding philosophy. He calls it “Relational Holism.” As individuals, we cannot exist apart from our relationships with other people and with Nature any more than a whirlpool in a riptide or a bird in a gyrating flock can exist independently. We are nothing if not part of nature.

And of course it follows that that the natural world was not “put there” for us to exploit and commodify and destroy by turning “resources” into money. We are not a separate creation, so let’s disabuse ourselves of that idea.

Wood ends by exploring the metaphysical underpinnings of this view. He finds clues in quantum physics. An electron can be either a wave or a particle, and it can change from one to the other. Can it choose? Who knows? What would that mean? By extension, we are made of waves and particles. The particles are our physical bodies, and the waves are our connection to the outer word.

Thus, we are truly “At Home in Nature.” I have grossly oversimplified Rob’s analysis, so I would urge a careful reading.

My aforementioned 1994 Stein disaster ended when I was discovered by Brooks Hogya and his Wilderness First Aid team out on a long training trip. Splinted and safe, I thanked Rob Wood for his advice. How’s that for “universal consciousness”?

Time for a brew. “More cobbler, anyone?”

*

John Gellard spent his childhood in England and Trinidad, donated his adolescence to an English boarding school, earned an MA in Philosophy from the University of Western Ontario, and taught English and Drama in London, Ontario, for seven years. In 1973, he arrived in the West Kootenay where he felled and peeled pine logs on his “wild land” property and built a log cabin. Gravitating to the city, he taught drama for thirty years at Vancouver Technical Secondary School and Kitsilano Secondary. He still helps run writing workshops for students, notably (since 1993) an annual overnight retreat on Gambier Island. His articles have appeared in the Globe and Mail and the Watershed Sentinel. He takes an active interest in environmental issues and travels extensively in B.C. He lives among friends in Kitsilano and on Hornby Island, has two grown sons, and retired from teaching English and Writing at Kitsilano Secondary School after being named Canada’s “Best High School Teacher” in a Maclean’s poll in August 2005.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster