#194 Lill Emerson: Raincoast educator

MEMOIR: Lill’s Story: Reminiscences of a Country Schoolteacher

by Lillian Emerson

Edited by Mary Novik and Ned Young

First published Nov. 4, 2017

*

We are delighted to present these memoirs of Lillian Emerson (1913-2003), a Vancouver Island teacher in the 1930s who became the mother of award-winning novelist Mary Novik.

Born in Victoria to English parents, Lillian (Lill) Maud Young spent a year training as a teacher at the Provincial Normal School (now Camosun College) in Victoria before landing a job in 1933 at Bloedel, a logging camp at Menzies Bay, ten miles north of Campbell River. Lill’s memoirs are set in schools, camps, and communities in Campbell River and Comox until 1940, when she married logging company surveyor Gerry Emerson.

These memoirs were made possible by Lill’s younger brother Ned Young (born 1920) of Thetford Mines, Quebec, who describes their genesis:

During the summer of 2000 I spent a few weeks visiting my sister, Lill Emerson, in her Langley, B.C. home. As she was approaching her eighty-seventh birthday, I persuaded her to record on tape some memories of her eventful life. As a teenager who had never been away from home, she had been suddenly thrust into the daunting job of teaching simultaneously all eight grades in a small, one-room school in an isolated logging camp. When I handed her the microphone, she sat back and closed her eyes, then proceeded to recount the adventures which I have transcribed on the following pages.

Mary Novik noted in an email to The Ormsby Review that many of the people in the story “are B.C. pioneers in their own right. In particular, I’m amazed at all the mountain climbing, backcountry skiing, and driving in ‘prehistoric’ vehicles that those young schoolteachers did. They were way ahead of their time. I was always glad that my mom, who went on to have six children, had many adventures before she settled down.” – Ed.

- Getting to Bloedel.

When Normal School was over, I had to face the problem of finding a job. This was in 1933, at the depths of the depression, and there were few schools available, especially for new teachers without experience. Whenever there was a job advertised in the paper everybody applied. I used to write applications on an old typewriter, using carbon papers to get additional copies. Of course, the main application was done in my own, very best, MacLean’s Method handwriting.[1] I wrote over sixty-five applications, but received no acknowledgements, let alone a job.

One day at the end of the summer I was walking in town and met Eleanor Anderton, the sister of an old friend who had been with me at Public School. Eleanor, who had been teaching during the year at a school in the interior of B.C, was looking very sad, and explained that she was on the way to the telegraph office. She had just been offered a job much closer to home, but, being after an August 15th deadline and too late to cancel her present job, she was obliged to refuse it.

I got very excited, and persuaded her to wait until I was able to get some money from my father who worked at the Canadian Pacific Railway machine shop on Belleville St. and go with her to the telegraph office. Then, as she sent the message refusing the new offer, I sent one saying I would accept it. A reply soon arrived saying I was appointed, and that they would expect me to report the following Monday at Bloedel, at the north end of Vancouver Island. I had never heard of the place before and called it “Blow-ee-del.” This was a Saturday morning, to be followed by Labour Day on the Monday, and I had to be there ready to start teaching the following day, September 4th, 1933.

I had a very busy weekend, getting clothes and books ready. Mom let me have the old trunk she had brought over from England twenty years before, and I had a little suitcase as well. Then on Monday morning I went to the bus station and asked for a ticket to Blow-ee-del. Nobody knew where it was but the agent looked at a map and said there was a logging camp with a similar name, ten miles north of Campbell River. He said he could not sell a ticket up to there, but could sell one to Nanaimo, another from there to Courtenay, and a third to Campbell River which was as far as the stages went. He added that I would have to find my own way from there to Bloedel.

Fortunately there was a taxi which picked up passengers at Campbell River and took them further north. As it was a long weekend, the loggers had been down to Campbell River for a good time, and the taxi soon filled up, with my suitcase and trunk tied to the back. On I went for ten miles over washboard roads, down a steep hill to the end of the road at the waterfront on Menzies Bay, arriving there at 7:00 P.M. That was the Campbell River Timber Company site, called Garrett. My destination, the Bloedel camp, was still further along the bay, and the only way to get there was to walk.[2]

It was pouring with rain, and the taxi driver, Joe Zanatta, offered to help me get there. We had to go around the Campbell River Timber camp and cross a floating bridge over the mouth of a river. This bridge consisted of four lengths of pairs of logs with planks nailed to them, and with a small, shaky railing on one side.

The tide was out and the logs were all uneven as they partially rested on rocks on the river bottom. Joe helped me across and carried my bags for me. He got a couple of the lumberjacks to carry my trunk across the river and left it at the side of the tracks, saying he would get them to bring it up on a speeder later.

After walking up the logging tracks on the other side of the river we came to the Bloedel camp. By this time I had learned the correct pronunciation — “Blow-del” — although at times I thought “Blowed t’hell” to be more appropriate. The lower camp, where I was to be stationed, had a cookhouse, bunkhouses for the men, a machine shop for repairing the rail equipment, a two-story office for the bigwig of the camp with a “store” on the ground floor.

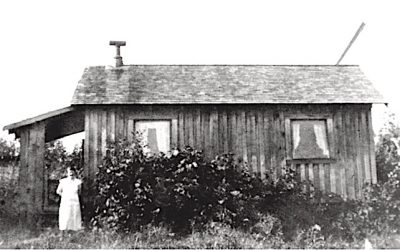

The few houses for the family men were on a bit of a hill beyond the machine shop. Joe spoke to a man in the office, a Mr Porter, who took me up to my little cottage. We had to go around a number of logging cars lined awaiting entry into the shop the next day, then up a big hill and along a boardwalk. It started with four planks, and then went to two planks until we got to the cottage that was to become my home. Of course it was locked, and it was now dark and late at night.

- Living quarters.

Fortunately Mr Porter knew the official trustee, a Mr Atkins, and went off to search for him. Mr Atkins had been away with his family all day, and had just arrived back. He was very surprised to find me there and came up, unlocked the door, and welcomed me to Bloedel.

There were two rooms in my little cabin. The front room, eleven feet square, had a wood-burning kitchen stove in it, a camp cot, built-in cupboard, good-sized sink, and three windows. The second room, eleven by seven-and-a-half feet, had a big double bed, a nice ivory dressing table, a chair, and a library table. The floors were painted, and there was a linoleum square in the kitchen and two small rugs in the bedroom.

It was a very nice, cosy place, and I liked it there. There was electricity available, but only from seven-thirty in the morning until ten o’clock at night. There was running water to a sink, but of course it was cold. Warm water was obtained by heating it on the wood stove. An outhouse nestled in the woods behind the cabin.

Each room had a window with a lovely view looking out over Menzies Bay. I never tired of looking out and watching the boats passing through the Narrows and past Ripple Rock. Sometimes they were not able to get through because of the strong tidal flow, and had to back down. One time when I looked out, I saw my Uncle Charlie’s boat, stuck and unable to get through the passageway. Of course I couldn’t get in touch with him or get out to see him.

I enjoyed living in that little place, but it was very difficult to get the stove to work. I received wood to keep it going — big blocks that they brought in — and I hired one of the schoolboys to chop it for me.

On my first day in the camp I went down to the store to buy some groceries. There I discovered that they only sold a little canned food, along with Copenhagen snuff, leather shoelaces, candy bars and logging supplies, but no groceries.

Although Mrs Atkins gave me a loaf of bread and a can of milk I practically starved all that first week, not having the food nor the time to cook it. One of the pupils brought in some muffins, and Mrs Atkins invited me for dinner at Friday noon, so I was a little revived.

A government scaler heard I was having trouble with the stove and knocked on my door to offer his help. Although I had by that time overcome the problem I was thankful for his visit. He thought the local people could have been a little more thoughtful and helped me through that first week. He went away, but came back a short time later with three parcels. He was on the good side of one of the cooks in the cookhouse, and scrounged for me a loaf of bread, some slices of roast beef, some cookies, some shortbread, and a huge lemon pie.

A little later Mrs Blakely sent two of her children over with some venison meat for my supper. The hunting season had just opened and I saw one man go out with his red cap, and in less than fifteen minutes he was back carrying a deer.

The families in the camp used to send down to Woodwards store in Vancouver for groceries. The supplies were sent on the Union Steamships boat, the Chelosin, which stopped at Menzies Bay twice a week with the orders. I soon learned how long a loaf of bread would last before it went mouldy, that fresh meat would only last two or three days, and that when canned milk and sugar ran out, black tea didn’t taste too bad. I finally learned to order once a month using mostly canned goods, meat, and vegetables.

One of my favourite meals was to put some water in a kettle on the stove to boil, put an egg in the water, and place a tin can of spinach alongside. By the time the water was boiling, the egg was cooked, the spinach was hot, and there was enough water for hot tea. I put it all on a plate, and that made a good supper.

- The school.

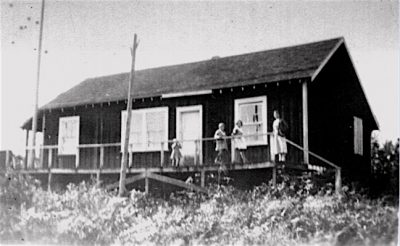

The school itself was right next door, about six feet from my cabin. Two outdoor toilets were a little walk out the back, one for the boys, and one for the girls, which was also for the teacherage. The school was an old house that had been converted into a school and had been brought from another location, the same as all the other cottages in the village. They were all built on big skids of huge logs so that they could be dragged from one place to another when the camp was relocated. They would either be floated away on barges or put on a rail car.

The stove in the classroom was a big Lumberman boiler-type thing with a piece of flat metal welded on top, and with some two-by-fours to hold up the chimney. This not only heated the building, it also enabled the teacher to put on a kettle, and the students to toast their sandwiches at noon hour. The school bell was just an iron bar bent into an open triangle hung up by a cord, with a metal rod to bang it with when calling the children into class.

The desks in the classroom were nailed to two-by-fours, and placed in rows. This made it very difficult to clean, as the broom had to go down under the desks to sweep from one side to the other. Of course the teacher was also the janitor, and it wasn’t exactly an easy place to clean. The wooden floor was oiled, and at least it kept the dust down.

Twenty-four children arrived for school that first morning. I didn’t know where they came from, because I had only seen about five houses on the tracks. I learned later that there were some who came from the Campbell River Timber Company camp, and another half dozen from the Lambs Logging Camp on the other side of the bay. Their ages varied from six to sixteen. There were two in the grade one class and one each in grades seven and eight, with the others spread out in between. I had no idea how I was going to cope. Finally I managed by spending a lot of time with the little ones, teaching them their lessons, and typing out instructions for the older children. This gave the older children something to do while I was busy with the younger ones.

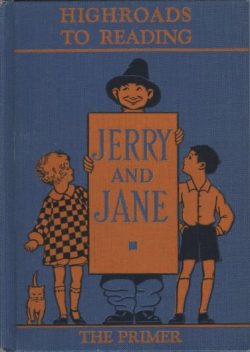

There were no library books, just the small issue of texts from the government education department down in Victoria. If the previous teacher had not ordered enough I was just out of luck. Fortunately I had brought along some of my own books and was able to use them.

The only way I could work with the class was to double up on some of the lessons. For instance, with the geography and science lessons I could teach two or three grades at one time. It was important that they know the geography of Canada, of England, and of the world, but it was impossible to do it all in one year. Consequently I arranged to cover one area each year. Eventually they all got the curriculum covered.

With arithmetic, spelling, and reading all the pupils had to have their own books, and it was very difficult to get the work done. I used to spend hours after school writing out exercises on the board for them to copy. In those days there were no workbooks to accompany the texts. They had to copy an exercise from a hardcover book onto a paper, and then to do it and get it all correct.

It was very difficult for the children. Half the time they would copy it incorrectly, so it was impossible for me to correct them all at the same time. For the grade one and two students it was very important to get the exercises ready for them on the board. For their reading I considered phonics to be important. Teaching with phonics was later deleted from the school curricula, but I found that children who studied by using phonics learned to spell well.

I always got a kick out of one little boy, Clayton Calder, who had come along the tracks from Lambs Camp, along with two or three other little children. He always seemed to have his gumboots on the wrong feet. When we said the Lord’s Prayer in the morning and I opened my eyes to see if everybody had theirs closed, I would see this little chap with his boots on the wrong feet, looking like Charlie Chaplin. It was difficult not to laugh.

I thoroughly enjoyed teaching at Bloedel, but I never worked so hard in all my life. I got paid ninety-five dollars a month. That was good pay for the time, because it was a big class, and there were three camps supporting us. Most teachers in their first year got seventy-nine dollars, which was the minimum wage. [2b] In addition, I received furnished lodgings rent-free, although I did have to provide my own food. The salary now seems minimal, but must be placed in perspective. Fifteen cents worth of T-bone steak that Mrs Atkins brought me from Campbell River lasted for two days, and the remainder had to be thrown out on the third day because it was going bad. Another time, for twenty-five cents I received five lovely lamb chops. To avoid the problem I had with the steak I ate two chops at noon one day and two for the evening meal, then the last one the following day. There was no refrigeration.

- Teaching.

The class itself was very difficult to handle, especially for a teacher who was only nineteen and away from home for the first time. However I was kept so busy trying to get things lined up for the next day that I didn’t have time to get homesick. A lot of the little children in that class were simply delightful. I still remember some of the names, like Clayton Calder, like the little twins who came all the way from Lambs Camp, like the little Japanese girl, Yayeko Adachi and her big brothers, Roy and Harry, and their friend Hirohiko. They were lovely children, and really well behaved. The children in the class knew they had to put their hands up to ask or answer a question, and at first it seemed that all I could see was waving hands. During the first week I dreamed of waving hands, and thought I would never get over it.

The teacher in the upper camp, Camp 5, some distance up the tracks, was an old hand after five years. He came down to see me. Harry Parker was such an odd fellow that the children laughed at him, but they never laughed at me. They always stood beside me – they were good kids. Some of them were very bright, and, of course, some were not so bright. I taught them as best I could, and the students got whatever they could out of the lessons.

One of the most difficult challenges in that first term was that the two students in the Grade 7 and 8 classes wanted to go on to High School. This required that they pass a government examination called the Entrance Exam. All year round, therefore, I made sure that these students received all the necessary instruction. Since grade seven students were going to have to do the same history and geography the next year, I taught both grades together, and that cut down the workload a bit.

The other classes were average groups and we did our best to get through the curriculum for each grade. It was not all work, and we had lots of fun there. We studied Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, written in 1820, in the Grade 8 English class, and the students enjoyed it so much that they played horse and rider and jousting outside in the field later. Of course the field was just a little patch of roughed-out ground which had been logged off, with stumps sticking up all over the place.

- Accident in the schoolyard.

One recess several boys came rushing in crying and shouting that Eugene Weber had fallen and broken his leg. He had been jousting with his young brother on his shoulders, stepped on a root and fell over. With the additional weight, he went down awkwardly onto the ground, and when I got out I found him with his left leg strung over his right shoulder. I didn’t know what to do, so put a blanket around him and sent one of the boys down to the machine shop to get help from the men there. They arrived with a stretcher and saw that the young lad had a dislocated hip and a spiral break of the leg bone. Although I had previously had first aid training at school as well as from my father, there was no way I was going to touch that boy.

The men phoned over to the Campbell River Timber camp for Eugene’s father who was the engineer on one of the small boats that pushed the logs around. They decided that the easiest way to get the lad to the hospital in Campbell River was to put him on the boat. Eugene was in the hospital for a long time, and I didn’t want him to miss out on his school year.

When he was recuperating at home I used to go over to his home on Saturday nights to give him some instruction and assignments for the following week, and pick up his work from the previous week. I would have supper there, and, after Eugene was put into bed, his mother and father would invite a couple of people up from the camp to join us in a game of cards. Although the boy eventually got over his injury and he grew to become a tall man, one of his legs was always a bit shorter, and he had a little limp.

One Saturday I had a surprise visitor, Ben Sivertz, a chap who had been at Normal School with me, called in to see me.[3] He hadn’t got a school but did find a job on a tugboat. They were stopped because the tide was against them at the narrows and they had to wait till the tide turned. He came over with me to see Eugene and we had a pleasant time together. Another time a friend of my brother, Ed Roskelley, who also worked on the tugs dropped in to say hello.

I had some interesting experiences while I was at Bloedel. One Saturday afternoon I had been doing my housework and saw one of my pupils, Dodge Parker, sauntering up the path. He was about ten. In his hand he was swinging a duck which he proudly presented to me. He had just shot it in the water, and was obviously very pleased with himself. He was such a nice kid.

I feathered it with great effort, lit the stove, and put the bird in the oven to cook. I kept testing it until I was sure it had been in long enough to have been cooked right through two or three times. I also cooked some potatoes and prepared some gravy, then sat down to eat the thing. I couldn’t get the knife through it and had to resort to tearing it off with my teeth. What juice did come through was so fishy it almost made me sick. Of course I thanked little Dodge very profusely, and never told him the true results.

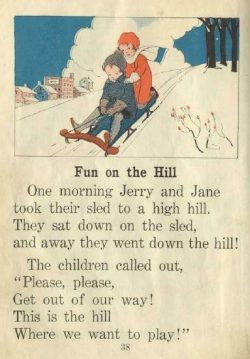

I recently found a copy of an essay which Dodge Parker wrote when he was in grade six. It was dated Oct. 24, 1934, and bears repeating here, not only as a representation of his work but also as an indication of the conditions which the students had to face in attending school.

A Composition by Dodge Parker Grade 6. A Rainy Day

- Rain in the City. Some people do not think much of rain, especially the city people. The children go to school in cars or streetcars if it is any distance away. They can play games or many other things in buildings specially made for them.

- Going to School. In the country here, we go to school by boat or by walking. In winter we go by boat because we can’t cross the floating bridge in the mouth of a river, because the sea comes so high that the ends of the bridge don’t come close enough to land to let us pass without getting wet. If we go by boat we usually get our feet wet from getting in and out. When we are safe on the rail-road track the train usually has to pass, so we have to move into the wet bushes for another soaking.

- The Games. By the time we get to school we are as wet and miserable as anyone could wish to be. The teacher brings in a few games and we have as much fun as possible in our condition. This just describes one rainy day, but that is enough, I should think.

*

The two school toilets were at the back of the school. I knew what the girls’ toilet was like, but I had never been into the boy’s toilet. In those early days young ladies just didn’t go into the boys’ toilets, but by Easter I started wondering who looked after it, since I was the janitor. When I finally went in I was so shocked that I immediately went down to the store and got some lye. I poured it all over the place, and, when I was finished with that toilet, a two-holer plus a urinal, it was quite clean. After that I told the boys how to behave, and always inspected it to make sure that it stayed clean.

You never knew what problems you were likely to face as a one-room schoolteacher. There was a definite lack of books, especially workbooks. In order to provide the students with work sheets I had to prepare them on a jelly pad. This was something that was made with a gelatin from a drug store. The melted liquid was poured onto a cookie sheet, and, when gelled, permitted the reproduction of perhaps ten sheets of the same exercise out of one pad, using a hectograph pencil or hectograph ink and newsprint paper. Of course it was necessary to get copies for all the students, and we had to wait until the next day before getting more sheets off the same pad. I had made two pads so was able to get four exercises at a time.

- Visit from Mother.

During that first month on the job I was so busy that I had little time to write home. Of course there were no phones, and there was no other way to contact the folks at home to let them know I had arrived or how I was coping. Although my brief letters were upbeat my mother, Maud Young, was very worried and decided to go to Bloedel to check on me.

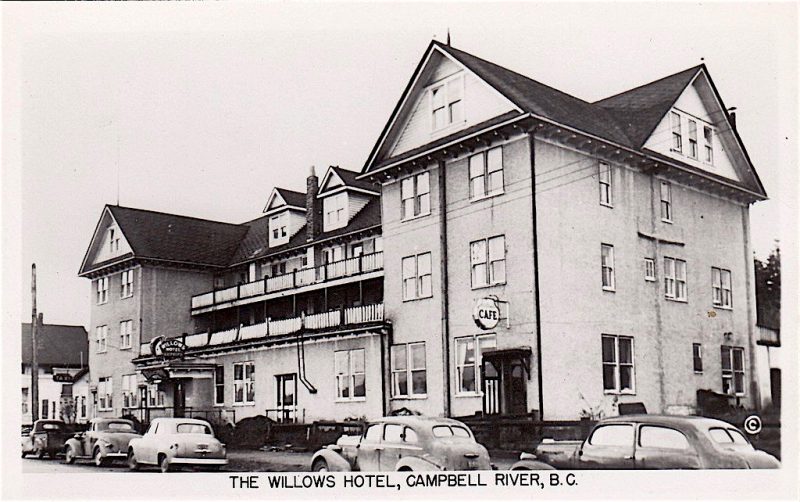

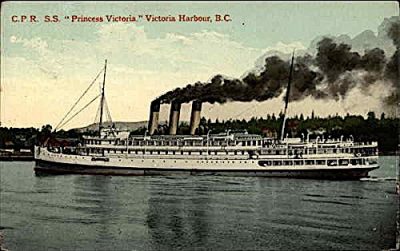

In order to save the bus fare – Dad got passes on the CPR boats – she went by boat from Victoria to Vancouver, then on another CPR boat to Campbell River, where it arrived at 3 a.m. She carried her grips over to the Willows Hotel where she got a room for the night. There was quite a storm blowing but Joe Zanatta was still driving his taxi and he took her the remainder of the trip to Bloedel, as he had with me.

She was absolutely scared stiff crossing the little floating bridge and walking up the tracks to my little cabin. It was September 21st when she reached Bloedel, about two and a half weeks after my arrival. When she arrived in the early afternoon she realized I was teaching, so, like the good English mother she was, she swept the floor, made the bed, built a fire, and made herself a cup of tea while she waited for me.

At recess time I dashed into the hut to get a drink of water and was amazed to see my mother standing there. She said I looked like I had seen a ghost. I was just preparing to give a singing lesson, but it certainly put a damper on it, because I couldn’t sing a note. By the time she arrived I had not met anybody except a few of the close neighbours, and at first I think she was ready to pack me off home again.

While she was there, the parents of one of the Grade 6 students, Dorothy Probert, invited us down for the evening. We walked back along the tracks in the dark, and Mom heaved a big sigh of relief when she got in safely. She stayed with me for a week. Before she left I heard there was to be a dance on the following Saturday in the community hall that was beside the schoolhouse. My strict instructions from Mom were that I was to close and lock the door, pull the blinds down, and to go to bed. I was not to go to that dance. As I was used to obeying my parents I didn’t go to the dance, and went to bed.

About 12:15 a.m. on the night of the dance a man came banging on my door, trying to get in. Mr Blakely saw him and shouted at him to leave. He did, but only after puking all over my back steps. Later on, I am told, I had another caller, but I was too dead to the world to notice. The dance lasted until after 4 a.m. and many there got pie-eyed. There were three or four small fights in the hall, and one big one, according to the children in class later. They knew all about it. Edna and Sonny even told me about the fight between their mama and daddy.

Two men walked into Atkins’ place, took seats on the chesterfield, and made themselves at home with a case of beer – until Mr Atkins chased them out. Another man went to Mr Blakely’s house after the dance and Mr Blakely had to threaten to “fill him full of lead” before he would leave. A short time later he returned, saying he had forgotten his hat. He thought their place was the dance hall.

The few rowdies had come from the other camps in the woods. Actually, by staying home I missed a good time, as well as the opportunity of meeting some of the parents and many young people from those logging camps who were just out to have some fun for an evening. There were some very fine people at Bloedel and the neighbouring camps. I don’t remember ever having another dance in that hall. The only time it was used was when I put on a Hallowe’en or Christmas party, or something of that nature.

Mom took the taxi back to Campbell River and the CPR boat to Victoria, happy in the knowledge that there were no serious problems and that I was going to be safe. Although I was very busy all the time, I still tried to write a letter home at least once a week.

- Techniques of teaching.

When we were teaching the other classes the grade ones had a very busy time. We had what we called letter cards. The students had to pick out the letters and make them into the words that they saw in the book. They would usually have a page done by the time I finished with the higher classes. For the arithmetic lessons they had number cards that were placed together to form little equations. We also had some pegboards, each with a hundred pegs. By the time they had all the pegs in I managed to complete a lesson in another class.

To teach writing I put the little ones at the blackboard drawing pictures, and later copying letters. Eventually they learned how to print, how to write, and how to make their numbers properly. After that they were able to work on paper.

Not having much paper to use I bought plain newsprint paper from Clarke & Stuart’s in Vancouver. I would copy the letters and characters on paper from the jelly pads, then it was not too difficult for them, for they had something to follow. The problem was that I did not have enough jelly pads for all the grades. I only had two, and each of those I divided into two halves, enabling me to get exercises for four classes. The teachers today certainly have it easy with their photocopiers, when compared with all the nonsense we had to go through.

There was a blackboard stretching across the front end of the building where my desk was. I would write a few arithmetic sums or problems onto the board and have them copy them into their scribblers. I soon discovered that it was a very difficult task for the children to copy from the vertical board to the horizontal papers on their desks, but eventually they learned how to do it.

All the classes from grade three to eight had silent reading lessons where they studied from ancient readers. Those readers were the same old green books, called Canadian Readers, from which I had learned to read at Oaklands School. Unfortunately there were no workbooks to go with them, although some arrived after my second year on the job. All instructions had to be written on the blackboard for each of the eight different classes. It wasn’t easy to get enough work lined up ahead to keep them all busy at the same time. That was when the hectograph pads came in handy.

At Normal School we were required to learn how to make a timetable, dividing the day into ten-minute intervals. Each class was supposed to get a ten-minute assignment, but with eight different classes it meant that in that ten minutes I had to give them enough for the ensuing seventy minutes to be done on their own. Nevertheless that first class of pupils was the best I ever had, because they really wanted to learn. We had lots of fun as well.

All the subjects were taught in the same way. Whenever possible I grouped the classes together if they could be given similar assignments. For instance I would put the grades two and three together for spelling and phonics. Grades 4 and 5 frequently worked together, and grade six worked either with the grade five or the Grade 7 seven class. The sevens and eights always went together. There was a small space at the back of the classroom where the sevens and eights sat together, using their own blackboard. In the evenings I would put instructions on that board for them to follow throughout the following day, so that I did not have to stop continually to tell them what to do.

Since the students had to work so much on their own it meant my checking and marking it later, and the job was horrendous. It was impossible to do it all during the class and I had to work at it after school when the children were no longer there.

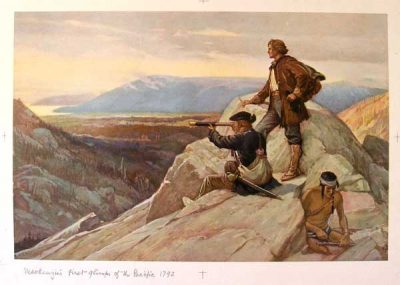

I loved teaching geography and Canadian history. For that I did a lot of studying of the explorers of Canada and recounted their exploits to the students. I would copy out maps and have the pupils trace the routes followed by the explorers.

Artwork was fun, as I was able to group everyone together. All the classes did similar art projects. The senior group had to have their work kept in special folders, so that it could be handed in for their High School entrance examinations. The smaller children, however, were always proud to take their work home with them. We used to shellac the drawings and paintings so that they shone and were quite brilliant. We used a lot of poster paints for that, and it was all good fun.

During the first month the storekeeper’s wife, Mrs Marden, arrived back from a trip to England. I remember her wearing a brand new dress to that dance. It was a gorgeous, bright red dress, and she was the belle of the ball. Some time later I got to know her quite well, and she invited me to have dinner with her and her husband on Friday nights. While there I was able to have a proper bath in her bathtub, instead of in the little tin thing I had in my cabin. They had a car and often when they were making a trip to Campbell River or Courtenay, or some other town where there were dances and other entertainment on the weekends, they would take me along with them. I used to enjoy that.

Mr and Mrs Marden were very good to me throughout my stay at Bloedel. On one trip to Courtenay to see a show they decided to go into a beer parlour for a drink. After much hesitation I agreed to join them but requested a glass of water. It was my first time in a beer parlour, and it was quite an experience. I remember one woman who had probably imbibed a little too much noticing my glass and exclaiming to all within hearing, “Well that’s the weakest beer I have ever seen!” much to my embarrassment. However I had a good time and it was nice to get away from the camp.

- The school inspector.

One time we went to Courtenay and saw Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald in the movie Rose Marie. I was terribly impressed, and the next morning I lay in bed thinking of that wonderful show and the lovely music. Later I was singing the famous song, “Oh Rose Marie I love you” out loud when somebody knocked on the door. There was Mr Gower, the school inspector. He had arrived earlier, let himself into the school, and went through my desk and all my papers. He checked my workbooks and plans for the next week to make sure I had everything in order. It was one of the meanest things anyone could possibly do.

Mr Gower was an old-style school inspector, one who considered it his job to criticize everything he saw. For example, he had a little Grade 2 student read to him. When she read the sentence, “I have been to the store to buy some candy”, he severely criticised her for pronouncing the verb as “been,” with the long “ee,” instead of “ben,” or “bin.” I thought it to be terribly mean of him to hold that little girl up to ridicule before the twenty-three other students in the class. Luckily I did manage to get a fair report from him, and, by the end of my four years in Bloedel I was getting good reports.

I was really quite annoyed with Mr Gower, the way he was coming in all the time, but my back got stiffened up a little, and I got used to him. He was probably a bit angry when he arrived, because he lived in Courtenay and had to drive the forty miles up to Bloedel over that terrible road.

I had much pleasure teaching music. The older children didn’t mind singing the nursery rhymes with the younger ones, and also enjoyed the songs from the Coney-Wicket text we had used at Normal School. I had a little wind-up gramophone with some old Caruso and Galli-Curci records, as well as a series of records about the instruments of a symphony orchestra. We would listen to the different instruments on our few orchestral records to see if we could recognise them. Mr Gower was so impressed he later asked me to give a talk at a teachers’ convention at Nanaimo on the subject, “How to teach music in an eight-grade school.”

While in the class we would often hear the whistle of the trains coming down the tracks from the upper logging camps. If they gave four blasts it meant, “Clear the tracks we are coming in to the boom.” If there were six, or seven, or eight blasts it meant to get the first aid man, as there had been an accident. The students were always worried when they heard that warning, wondering whose father it would be who had been injured. It was always disruptive, and I never knew quite how to handle that situation. Fortunately it was never one of their fathers while I was there.

- Life in a logging camp.

One night I had a visit from a Miss Bowron who worked for the Education Department. She arrived at my doorstep and explained that her job was to check that the teachers were comfortable and were not being maltreated by the people in the district.

I had never heard of her before. She talked on and on, until it came time to go to bed. I explained that I had no place for her, but she said she would be satisfied to sleep on the couch in the front room. Then she asked for a hot water bottle to keep her feet warm during the night, saying it would also provide tepid water to wash with in the morning. It was the only time she ever came to visit me, and I believe the job was later cancelled. As I recall, she was the daughter of one of the former B.C. Premiers, but I am not sure.[4] Of course I had to feed her, and, although I had next to nothing in the house, I managed.

There was always very little food left in the house at the end of the month when I sent down my order for groceries. At first I wondered how one could possibly order enough for a complete month, but I learned quickly. If I ran out of milk I had to make do without. It was then that I adapted to taking my tea without milk or sugar. I would always buy vegetables, but there were few that would keep for an entire month. Many of the large families ordered twice a week. The supply boat, the Chelosin, arrived on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and when the kids heard the whistle blow they would get all excited, wondering what their parents had ordered for them.

I didn’t have much chance to learn how to cook while I was at Bloedel. The wood stove was a terrible nuisance; I had to make do with the top, as the oven had practically no heat in it at all. That stove was the only supply of heat for the cabin, and it was very cold in the winter, especially overnight. Eventually the trustees provided me with a little round wood-burning heater, and by adjusting the draft, I was able to keep it going for most of the cold nights. As the heater was on the opposite side of the room to the stove the smoke pipe had to cross over the room to join into the chimney.

- The joy of winter.

The first winter was very severe, with lots of snow. The logging camp was closed down, but the school continued on as usual. One day when I looked out I noticed the snow was all pink, and there was a terrible roar in the house. I dashed outside and found that the chimney was on fire. I was scared to death, as a general fire would have burned all the adjacent buildings: the school and half a dozen nearby houses. It would have been a disaster. I shouted to my neighbour, asking what to do. He said there was nothing to be done except wait until it burns out. It was the creosote in that long pipe across the kitchen that was burning.

The following winter was worse than the first. I still have letters that I sent home in which I described the conditions. It started off with heavy floods, and when I returned after the Christmas holidays, I found the floating bridge was turned over. Then several weeks later there was a heavy snowstorm and school had to be cancelled for fear of the roof caving in. Along the paths the snow was shoulder high, and, since the pipes were frozen, I had to pack water from below or melt snow. When the school re-opened there were only fourteen children present. Some came in boats, some along the track through five feet or more of snow. The school stovepipe was full of snow, and when we lit the fire it filled the room with smoke. Mr Smith came to help and knocked the pipes down while the fire was lit. When he got them back up, the snow melted and poured into the room. I had pots and pans scattered all around to catch the water. Then the roof began to leak at the back.

A month later, in another letter I wrote:

Boy! Has it been cold! I just about freeze every day. I’m cuddled up now beside the fire with my hat, coat and scarf on, trying to keep warm. Everything is frozen up. In school at 9 o’clock this morning the thermometer registered fifteen degrees F, and the fire had been on for nearly an hour. The icicles have grown to about five feet long. The snow is about three feet deep when you get off the path. I have to wear gumboots just to go the ten feet across from my cabin to the school. I have given up trying to thaw pipes, and have to carry water from the Mardens to last me through the day. The other day I took my hot water bottle to bed, but during the night kicked it onto the floor. In the morning the bottle was full of ice and remained that way till night. It struck me as amusing – a hot water bottle full of ice.

But there were bright spots, for, as I wrote on the following Saturday, “At 8:15 this morning Mrs Marden came in, lit my fire for me, and gave me coffee in bed. With her oil burner furnace she has tea at four o’clock in the morning, and, as it was so cold, she thought of me in my icebox.” She was a good friend.

- Yayeko Adachi.

There was a Japanese family in my class: Yayeko Adachi was a little girl in grade four, and her brothers, Roy and Harry, were in grades seven and eight. They were a very nice family. They lived down near the log booms, a long way down the tracks, and we saw very little of them except when they came to school. One day when it was raining very hard I placed my hooded cape over the little girl when she went home. The parents must have appreciated it, because the next day, when she arrived at school and handed me the cape, I found it wrapped around a lovely big cabbage.

One day Yayeko came to school dressed in her native costume: a kimono with a big band around the middle, little wooden shoes, and a parasol. She looked delightful. She was the youngest child of a large family. Forty-four years later, in 1976, after we had moved out to Langley, I had a phone call from Yayeko asking if she could come to visit me. She was living in Lethbridge with her husband who had a Japanese garden there. She was visiting friends on the coast with her husband and thirteen-year-old child. We had tea out in the back of our little old house, and had a very nice talk together. She told me about her life in Lethbridge and about the other members of her family. She had had six children and most had gone to university.

She told me all about the hardships her family had suffered during the war when all the Japanese people on the coast had been sent to camps in the interior of B.C. She met her husband there. I feel that interning those Japanese was a terribly black episode in our Canadian history. They were such lovely people.[5]

- The Atkins boys.

Mr Atkins, the school trustee, had two sons in the class, Douglas and his little brother Dean. The father arranged for Douglas and Harry Adachi to light the fire in the school early in the morning with four-foot lengths of logs. This meant that the school was always warm when the other children arrived. At lunchtime they would put their sandwiches on the side of the big stove and toast them, and often I would make them cocoa. The children who lived close enough went home for their lunch.

Douglas was a bit of a problem. He was about fourteen, and, of course, I was only five years older. One time when he gave me trouble I put my strap on the desk and warned him that I would use it if he kept up the nonsense. I had never used a strap before and was not sure what to do. However when he continued the nonsense I had to learn how quickly. The problem was that, when I swung the strap, he pulled his hand away, and I gave my own leg a big wallop. I finally managed to hit him twice on each hand. He went back to his seat a little bit sore, but I think I hurt more than he did. I did not like to use the strap, but often put it on the desk and threatened to use it if a child didn’t behave.

Dean Atkins was a quiet little boy, just a little sweetheart, but Douglas his older brother, was just at a tough age for a kid and was always feeling his oats. One day I saw him outside smoking, showing off before the other kids. That was too much for me to handle so I sent him home to his father.

- Gerry Emerson.

One time the company decided to extend their logging area and brought in a group of surveyors to mark off the property. They stayed at the base camp and were transported to the upper camp every day. My good friends, Mr. and Mrs Marden, decided that these young fellows should meet the teacher, and invited them to visit at the same time that I went for my weekly dinner.

Alf Bucklin, the leader of the group, was engaged to be married, as was Les Coles, and they both declined. The other two fellows, Alan Stewart and Gerry Emerson, did accept. Evidently Mr. Marden had told them that the teacher went to his home every Friday night for a bath. He said there was a knothole in the bathroom wall and they could have a treat. It was Gerry who told me later that this was how Marden had persuaded them to make that initial visit.

Alan and Gerry became rivals and they used to draw to see who would visit the young teacher in her cabin. I would entertain them with my gramophone, an old wind-up thing that made an awful noise. Alan said he wanted to learn how to dance, and we tried. He had attended the Royal Military College at Kingston and knew how to march, but he was a terrible dancer. Gerry, on the other hand, was not as interested in dancing as he was in looking through my microscope. It was one that had been loaned to me by Mr Chandler, a friend of my parents, and I used it in school for science lessons every now and then.

Gerry had never seen a microscope before – he had only had a grade eight education and there were few resources available in the little country town of Bradner in the Fraser Valley where he grew up. We viewed a variety of things under it, anything I could find around the kitchen. When I examined some old cheese I became really excited and started sketching the little bugs which came crawling out. Gerry, on the other hand, was aghast, and vowed he would never again eat cheese.

One day Gerry was walking over the logs where the booms were being made up, and fell in. Alan kidded him about it and sent him up to me with a letter pleading for me “to let this aquatic monster in.”

Les Coles, Gerry and I used to go on long walks. One time we went beyond the Lambs Camp and over the hills where we could look down on the fast tide streaming down the Seymour Narrows past Ripple Rock. It formed such a great eddy at the rock that logs that escaped the booms would be sucked down vertically into the swirling water, and be stuck there until the change of tide.

Ripple Rock was left in place for a long time as a possible platform for a bridge across from the mainland to Vancouver Island. Eventually [1958] it was blown up, however, as it was too hazardous for the ships passing by, and a bridge was deemed impracticable.

- Driving lessons.

In March, 1935 I experienced what I called in a letter home, “the most exciting weekend I think I’ve ever spent.” A friend invited me to go with him to Courtenay in his car and, as I wrote:

from about six miles out of Courtenay to Campbell River I drove all the way. Einer praised me like the dickens and could hardly believe it was the first time I had driven. I was fine while there was no car in sight, but suddenly I thought I saw headlights flash ahead. I said, “Oh golly, Einer, what will I do?” He replied “Och, you ninny, that’s not a car, that’s Cape Mudge lighthouse.” Next day I drove to Garrett and back to Campbell River, then we drove to Courtenay, had supper, and I drove all the way back to C.R.

That was a spark that inspired me, and encouraged by Mr Marden I began looking for a good second-hand car.

By summer I had saved up enough money to become really serious about it. Then one day I saw a car advertised for sale in the paper. It was up on blocks and had been since the owner had died, and now his widow was ready to sell. I went around to the place and found the MacMurchie brothers drooling over it, but they didn’t have enough money. The previous owner had taken such good care of it that he would drive around the block to find a place in the shade to park. It was taken off the blocks and for $400 the car was mine. It was a 1929 Dodge coupe. Dad asked a friend of his to give me some lessons, and two weeks later I drove the hundred and seventy-five miles back to camp.

Life became much easier then, as I could drive into Campbellton for my groceries. I often spent the weekend with the teacher in Campbell River and we would attend the dances together. We even joined the badminton club on a Friday night, and Mary would often return to spend the weekend with me.

I soon found out that owning a car was not all honey. Winter came and I had to drain the radiator after each use. Then next time out I would get a bucket of warm water from Weber’s house to fill it. Of course it required a crank to get started and that was more than my strength could manage. I used to stand on it to push it down, then pull to bring it up again until the oil warmed up enough for me to turn it over and get it started. I always carried a bucket of sand and a shovel to get me out of the snow, but I loved that car.

These days we take rapid, clear communication for granted, but one letter I sent home in June 1935, shows how far we have advanced. I had just placed a long-distance call home. It was such an unusual occurrence in those days that I immediately wrote: “How did you like me phoning? I didn’t know whether to or not; thought maybe you’d think I’d hurt myself. What did you think when you heard Bloedel calling? I couldn’t hear Nahdin very well.[6] Mom’s voice sounded the clearest, but she sounded nervous. What did I sound like? Was my voice clear or muffled? I’ll bet I sounded like a foghorn.”

Gerry Emerson and I became good friends, and it was a disappointment for me when he moved away to a new logging camp near Alberni. However it was not long after that I also moved away to take a teaching post at the school in Comox, a larger community sixty miles south of Bloedel.

- A new job.

When I went down to Comox to apply for the job a good friend, Mary Abercrombie, accompanied me. She was a teacher at Campbell River. I remember that on the way down we got a flat tire and I had to change it on the side of the road. I was interviewed by one of the school board members. When he asked my religion I did not know what to reply, as I didn’t know his, so just answered that I was Christian. That evidently satisfied him, as I got the job.

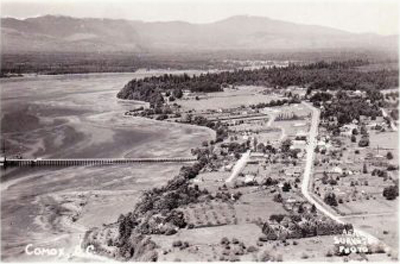

When I arrived at Comox in the fall of 1937 it seemed as if I had arrived at civilisation after living in the logging camp for four years. It was a very pleasant place. I boarded with a Mrs Piket on the corner of the main road into the town. She was a Scotswoman who had come to Canada many years previously. She went originally to Cumberland, where she met Mr Piket, and they subsequently moved to Comox.[7]

They made room in their home for several teachers to board with them. Miss Elderkin, from the High School, had the front room downstairs, and I another teacher each had a room upstairs. Our elementary school, which was only a block away, was a big school with four rooms, although there were only three classes of students. At the start I had grades four, five, and six, with forty-six pupils in the class.

I was kept very busy, but I enjoyed the experience very much. The principal of the school was May Hogben, a good principal and a good friend.

One of our projects at the Comox school was building birdhouses. Can you imagine the din, with forty-six students banging away making those little houses? Dad provided me with a little drill which was just the right size for drilling the entry hole for the birds. The students were very pleased with that project, and we had a photo taken of them, each holding his own birdhouse.

The other teacher taught the Primary room with three grades and forty-six pupils until she took a leave of absence, and Bud Feeney took over the primary class. On her return, she only stayed another year then left to get married. I took over her class and Reg Kelly was hired for mine. The following year another teacher was hired, thus reducing the size of the classes, and each of the four teachers handled two grades.

Mrs Hemming, the new teacher, drove from Royston each day. There was a piano in my room so I started a girls’ choir with practices during the noon hour. It was a fun thing both for the students and for me. A local music teacher used to come up to accompany us on special occasions. One year we took the choir to the Music Festival in Nanaimo and did very well, taking second place.

The second year I was at Comox I moved to the home of Mrs Carthew. She had come over from Scotland as a nursemaid when she was twelve. She made the trip on a sailing ship around the Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America. She remarked on the terrible experience of rounding that Cape during heavy storms with everyone sick. Although she felt terrible herself she still had to look after the children in her charge. The family settled in Cumberland, and she stayed with them until she met Mr Carthew who had a livery stable. He was a very prosperous young man, and they eventually moved to a large acreage in Comox where they raised cattle and a lot of hay.[8]

There was a short path through the fields from the Carthew home to the school, and I used to enjoy running back down that path to get my lunch.

On the flats below the house was an old Indian fighting ground. When their son, Jack, ploughed that field he used to turn up a lot of old Indian artifacts. He worked at a logging camp of the Elk River Timber Company, living there in a small cabin with his wife, Jenny.[9]

After a while Mrs Carthew, who was about seventy, decided she wanted companionship during the day as well as in the evenings, so I moved in with another young woman. She had two young children, and used to teach dancing in her home to make a bit of a living. I believe her husband had been killed in a logging camp accident. It was fun having the children at home as well as in the class, and we did lots of learning as well.

- Outside activities.

At Comox there was a bit of a library with lots of books, making it interesting for the students. While there I joined a ladies’ choir as well as a pro-recreation class. I also joined a hiking, mountaineering, and skiing club that had a cabin on the top of nearby Mount Beecher. Whenever I had an opportunity I went up to the club and I met many friends there, some who remained fast friends for many years. One was Mia Schjelderup. In the summer we would climb the mountain and in the winter we would ski. This, of course, was long before the development of ski tows and lifts on Mount Washington.

One September Mia and I went up with big buckets and collected wild blueberries. I sent a bucket of the berries with a twig on the top down to my mother. She had never seen a blueberry before, and really enjoyed them, especially with the twig on the top.

In 1938 I drove up to Courtenay from Victoria with a friend, Eleanor Peden. There we met with Mia Schjelderup, May Hogben, and Effie Guthrie, a local teacher, and all went on a six-day hike up to the Forbidden Plateau. We took a load of supplies on our backs as well as a tent. At the lake where we pitched our tent we met the man who was in charge of a camp up there on the lakeside, a Mr Tait. He took us under his wing and acted as a guide on our hikes over the mountains. We climbed nearly all the mountains on the plateau, even climbing Mount Albert Edward, reaching up 8,000 feet. As we approached the peak it was all shale, and it meant stepping two feet forward and sliding one foot back. At the summit there was a cairn, so we all wrote our names on a paper and put it in a bottle at the base of the cairn. We returned to Courtenay just in time to catch our pre-arranged pick-up at the beginning of the Dove Creek trail.

When I took over the primary class Reg Kelly took over my old class. He was a full-blooded Haida Indian. His mother and father – Rev. Peter Kelly — were very modern people, running a little mission boat that ran up and down the coast stopping at the little villages along the way.

In September of 1939, Reg Kelly, May Hogben and I rented several rooms at the Elk Hotel, down at the waterfront. The apartment was fixed up with a kitchen, one long bedroom which May and I shared, and a bedroom and sitting room in the next apartment. We would pick up food on the way home from school and share our meals and expenses. I was the only one with a car, so it was easy for us to get back and forth to the school, although it was not far and we walked most of the time.

Later, May Hogben moved on and Doug Fairbairn replaced her as principal. Doug was a local boy and a very pleasant chap. When the war broke out he joined the Air Force and was subsequently shot down and was never recovered. He had just married before joining the forces.

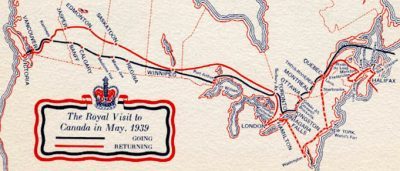

- The Royal visit.

It was in the spring of that year that the new king and queen, George VI and Elizabeth, visited Canada and Victoria. Naturally all the people up and down Vancouver Island wanted their children to see the distinguished visitors. A special Esquimalt & Nanaimo train was arranged to collect all these children, along with their teachers, starting at Courtenay and picking up groups all the way down the island.

From the railway station at Victoria we all marched the mile-and-a-half to Beacon Hill Park, where the royal visitors were expected to pass. There were so many locals already lined up that I advised my students to crawl through at the feet of the adults to reach the front for a better view. I managed to find a box to stand on, along with two other teachers, but it was not much use, as the royal car whizzed past in seconds. We then had to march back to the station to catch the train where box lunches were awaiting us. On the ride back up the Island we had a great time, with singing and group activities organized by the teachers.

While I was at Comox we put on a little operetta: Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel. I, along with some of the parents made the costumes, and the performers looked so sweet. One parent made a batch of gingerbread for all the participants after the performance. I felt that was a wonderful gesture. I think that putting on that operetta was my proudest achievement while at Comox.

I was asked to accept a little five-year-old into my class, Christine Cameron. Although the official starting age was six, her mother felt that she was so advanced it would be a shame to hold her back for another year, and I had no objection as long as she fitted in with the other students. Well she was such a bright little thing that, during a show-and-tell one day, she decided to sing a song for us, and sang it all in German. She was certainly ready for school, and was no trouble whatsoever. It wasn’t until years later that I saw her photo in the newspaper announcing she had won a scholarship to university to study chemistry. I was so proud to know that I had had a part in the start of her career. Her father was the CCF (Co-operative Commonwealth Federation) member of the provincial parliament for the Comox area.

While at Comox a number of interesting things happened. Living at the Elk Hotel we had quite a bit of fun. I think we scandalised the district by having both women teachers and a male teacher in the same cottage without a chaperone, however, I never heard anything of it.

- Marriage.

During 1938 Gerry Emerson and I got together again, and went over to visit his people at Bradner. When we returned Gerry got a job at Franklin River, a long way away. Not long afterwards I received a phone call from Mr Stewart of the Provincial Topographical Survey Department in Victoria, trying to trace Gerry.[10] I hastily phoned all the hotels in the Alberni area, finally locating him and passing on the message. It was as a result of that call that he joined the Survey Department in Victoria.

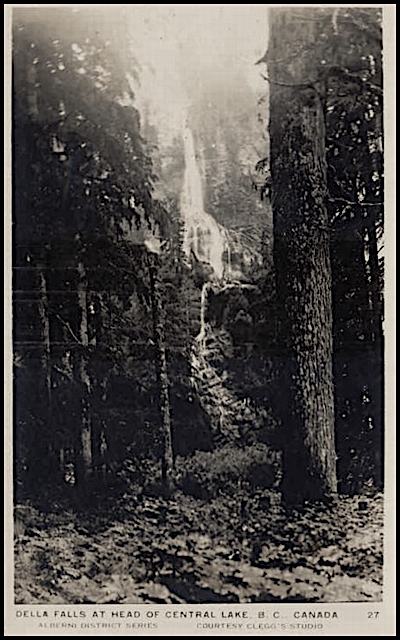

I think it must have been the Labour Day weekend of 1938, that Gerry invited me and my younger brothers for a hiking trip to see Della Falls in the interior of Vancouver Island. He was working in that area with MacMillan and Bloedel’s Logging Company at Franklin River. Ted, Ned and I left Victoria on the Friday afternoon. We had my car packed with our food supply and camping gear and drove through Nanaimo, branching off at Parksville to the Alberni road. This was new territory for me and the road was very narrow in those years. We passed through Alberni and turned off on the logging road to Great Central Lake.

Time was running short as Gerry had arranged for the camp motor boat to delay its departure till seven o’clock, just giving us time to drive from Victoria. About quarter to seven, and just a short distance from the lake, we got a flat tire! The three of us worked like a practised team to change the tire and get back on the road, arriving just in time to find an anxious Gerry pacing the dock, and the boat ready to leave. We unloaded and parked the car, then ran back to the dock and boarded the small boat. Great Central Lake is about twenty miles long so it was dark by the time we arrived at the north end. The boys put up the tent while I made some supper, and we settled down for the night.

Next morning we put our sleeping bags and a little food in our packs and started up the ten-mile trail through the big trees and thick underbrush, following the Drinkwater River up to the base of the Della Falls. Gerry had brought a canvas sheet that he put up as a bit of a shelter for us and made a fire to cook a meal. He showed us how to bend a forked stick to hang a can over the flames to heat some water for tea and heat a can of beans. We spent a cold night huddled together to keep warm as the wind blew right through the shelter. The boys put me in the middle so I was warmer than they.

We were up early Sunday morning to cross the creek and climb up the face of the cliff. The old prospectors who had mined for gold in the area had installed a steel cable alongside the path which helped them carry their ore down the steep slippery rocks, and this assisted us in our upward climb. Della Falls, with a 1500-foot sheer drop, is the highest waterfall in Canada. After the strenuous climb we were glad to sit down at the top and eat our lunch on the rocks by Della Lake. We couldn’t waste time as we had a long trek back to meet the boat to take us back down the lake. Needless to say climbing down was no easier and we had to break camp and hurry down the ten-mile steep trail to meet the boat for the return trip down the lake.

But the journey was not over yet. We left Gerry at the dock on the south of the lake, found our car and drove the one hundred and thirty miles back to Victoria. Next day I had to drive back one hundred and fifty miles to Comox to start another year of teaching. It may not seem far now, but it was a 1929 car and the roads limited the speed to forty or fifty miles an hour, and that only in the few good spots.

Gerry and I became very good friends, but it was a difficult arrangement, because all summer he was away in the mountains surveying, and in the winter I was away teaching. In any case, we became engaged in December of 1939. The trouble was that he was away all summer during the time that I was home having my holidays. We decided, therefore, to plan for the wedding to take place during the Christmas holidays, and were married on December 30, 1940.

*

Mary Novik is a Vancouver novelist. Her first novel, Conceit, is the story of Pegge, the daughter of the English love poet, John Donne. Conceit was chosen as a Book of the Year by both Quill & Quire and The Globe and Mail. As well as being long-listed for the Scotiabank Giller Prize, it won B.C.’s top fiction award, the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize in 2008. CBC’s Canada Reads named Conceit one of The Top 40 Essential Canadian Novels of the Decade. Mary’s second novel, Muse, is set in Avignon during the fourteenth century, when the popes resided there. Muse is narrated by the mysterious woman who was caught up in a love triangle with Francesco Petrarch and Laura. Muse was also published in French (Muse) and Italian (L’amante del Papa). Mary belongs to the Vancouver writing group SPiN, which includes novelists Jen Sookfong Lee and June Hutton. For more information, visit her website at: <http://www.marynovik.com> www.marynovik.com

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] The MacLean Method of Handwriting originated with a Victoria school principal, Henry Boyver MacLean. See Tom Hawthorn, “Millions of Canadians followed B.C. principal’s script,” The Globe and Mail, May 4, 2010. See https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/millions-of-canadians-followed-bc-principals-script/article4352963/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

[1] The MacLean Method of Handwriting originated with a Victoria school principal, Henry Boyver MacLean. See Tom Hawthorn, “Millions of Canadians followed B.C. principal’s script,” The Globe and Mail, May 4, 2010. See https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/millions-of-canadians-followed-bc-principals-script/article4352963/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

[2] This was Camp 1 of the Bloedel company. As Lilian’s future husband Gerry Emerson recalled, “I worked at survey work at Bloedel. It was for Bloedel that I was working. It eventually turned to Bloedel, Stewart & Welch, and then MacMillan Bloedel. It was Bloedel at that time.” On the Menzies Bay logging camps, see Jeanette Taylor, River City: A History of Campbell River and the Discovery Islands (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 1999), pp. 124-25.

[2b] “The annual salary of an elementary teacher at this time was about $780 and for a senior secondary teacher $1,100. There was no common or agreed to salary grid and women were paid less than men for the same work. The average class size was 45 with some classes in the high 50s. When women teachers married, they were asked to resign.” According to an article by Ken Novakowski, “1939-40: The Langley Affair,” Teacher Newsmagazine (BCTF), 24: 5 (March 2012).

[3] This is Ben (Bent Gestur) Sivertz (1905-2000), teacher, sailor, soldier, and Commissioner of the Northwest Territories in the 1960s.

[4] Bowron was secretary to Premier Richard McBride. On her career, see J. Donald Wilson, “`I am Here to Help if You Need Me:’ British Columbia’s Rural Teachers’ Welfare Officer, 1928-1934,” Journal of Canadian Studies 25: 2 (Summer 1990).

[5] On Yayeko Adachi and her family see also Peggie Law, “Old Friends,” James Bay Beacon (May 2016), http://jamesbaybeacon.ca/?q=node/1826

[6] Lill refers here to her younger brother Harold Nahdin Young (Ned), born 1920 and now (November 2017) living at Thetford Mines, Quebec. For a sound clip of his voice see: http://www.thememoryproject.com/stories/1806:harold-nahdin-young/

[7] For John Piket see Richard Mackie, The Wilderness Profound: Victorian Life on the Gulf of Georgia (Victoria: Son Nis Press, 1995), p. 252.

[8] For the Carthew family see Mackie, The Wilderness Profound, 163-165, 197.

[9] For Jack and Jenny Carthew and their farm see Richard Mackie, Island Timber: A Social History of the Comox Logging Company, Vancouver Island (Victoria: Sono Nis Press, 2000), 92, 94, 100.

[10] Norman Stewart, the Surveyor General of British Columbia.