#130 The making of Making Room

Making Room: Forty Years of Room Magazine

by Meghan Bell (editor) and curated by the Growing Room Collective: Meghan Bell, Terri Brandmueller, Candace Fertile, Taryn Hubbard, Chelene Knight, Lindsay Glauser Kwan, Cara Lang, Alissa McArthur, Navneet Nagra, Bonnie Nish, Rachel Thompson, Kayi Wong, and Lisa Xing

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2017

$24.95 / 9781987915402

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

First published May 23, 2017

*

When I began to think about reviewing this book, a Canadian historian expressed amusement at the mere idea of 1970s feminism in Vancouver as a serious topic, let alone an episode in real history.

When I began to think about reviewing this book, a Canadian historian expressed amusement at the mere idea of 1970s feminism in Vancouver as a serious topic, let alone an episode in real history.

Thus challenged, I felt compelled to charge ahead and write this review; otherwise I must conclude that the word “history” is not as I have assumed a derivation from Greek ἱστορία, historia, meaning “inquiry, knowledge acquired by investigation” (The Handbook of Historical Linguistics, 2005) but instead a compound of “his” and “story” distinct from the equal and opposite discipline called “herstory.”

1970s Vancouver feminism liberated us from more than lipstick and foundation garments. Something happened that has not finished yet. We had read Betty Friedan and Simone de Beauvoir, but more kept coming: Kate Millett, Gloria Steinem, Germaine Greer, Judy Chicago. We had our own Canadian talent: among them journalists Doris Anderson and June Callwood of Chatelaine, Eleanor Wachtel (who wrote the foreword to this book) of the CBC, Florence Bird, a.k.a. Arlene Francis, chair of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada.

In Vancouver, Pauline Jewett of Simon Fraser University was the first female president of any Canadian co-ed university. Enough women insisted on being addressed as Ms instead of Miss or Mrs that the form stopped being weird and began to appear on official forms. We had Kinesis, the publication of the Vancouver Status of Women. And we had Room.

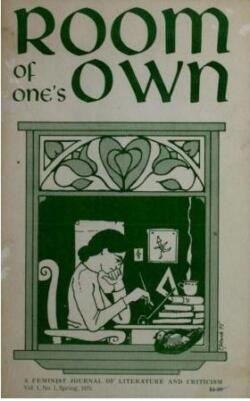

The founding members of the Growing Room Collective named their quarterly literary journal Room of One’s Own in homage to Virginia Woolf who, in her 1928 essay of that title, asserted that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write….”

Woolf, who recognised her own privilege, lamented that “privacy and free time were luxuries denied to all but a very small minority of women.”

In their 1975 inaugural editorial the Collective — Mary Anderson, Laurie Bagley, Pat Bartle, Penny Birnbaum, Lora Lippert, Gayla Reid, and Gail van Varseveld — expanded the meaning of “room” beyond physical and economic space to include access to publication: “The woman writer needs not only a private place in which to create but also ‘room’ in publication where she can communicate her ideas and feelings to others… a forum in which woman can share and express their unique perspectives on themselves, each other, and the world.”

The founding seven converged from a non-credit evening course on women in literature that Reid taught at Vancouver Community College. It was not a creative writing course, and none of the editors were “creative” writers, at least not yet. They were not planning to publish their own work; they were planning to enable others.

Reid explains: “At the time, writers typically got started by publishing in a little literary magazine (usually edited by men). So, Room would be a place where women could get started.”

And Reid continues: while Room “belonged in the feminist landscape, … there was no requirement that submissions should explicitly address sexism. We wanted to publish writing by women that was good writing, and we were convinced that there would be a lot of it around — and there was.”

Room’s founders called themselves a “collective” because they “believed we should work collectively as opposed to hierarchically. Collectives were the feminist norm: there were daycare collectives, health collectives. The impetus came from the left and it was very much part of the times.”

Nevertheless, the magazine has had a succession of strong managing editors, whose voices as spokespersons relate the narrative behind this anthology. For the editors as much as for the writers, Room offered a unique opportunity to prove themselves.

Room’s four decades frame the collection’s four sections, each opening with an interview between an editor of that era and a predecessor.

I made the mistake with the First Decade (1975-1987) of trying to read straight through before deciding that this is not the best way to read any anthology.

The great Dorothy Livesay, mother poet of them all, set me straight in her essay “Women as Poets,” written to review her own editing of Forty Women Poets of Canada:

One reviewer complained that ‘with few exceptions … the poems are wry, agonised, despairing. The subjects chosen are suffering, dark, hurt, lonely. There is very little joy. One wonders why.’ I think one knows why. This is the world we live in, the world from which one must free themselves.

These women wrote what they could not have written before they found a safe haven for their stories.

So I skipped around, dipping in here and there, taking a break, rereading some and finding quite a lot of joy, after all. The joy may be elegiac, as in Sandy Frances Duncan’s “Was that Malcolm Lowry,” later picked up for republishing in Vancouver Short Stories (1985), and in Marian Engel’s “The Smell of Sulphur.”

There is wryness, if not despair, in Audrey Thomas’s deconstruction of “grass widows” and “old maids” in “Untouchables: a memoir.”

We are closer to despair in “Ten Sketches” by Carole Itter, who recently received the 2017 Audain Prize of Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts. These writers, and others of that decade — Leona Gom, Daphne Marlatt, Lorna Crozier, to name a few — had not yet achieved their present status in Canadian letters.

The editor interviewed for the Second Decade (1988-1997), Mary Schendlinger, co-founder of Geist magazine, recalled that Feminism was still regarded as something for white middle-class women, but proponents of diverse issues were finding their voices, gender and race were in the mix, and “there was all this stuff flying, flying, flying around.”

With politicism came schism: Rape Relief vs WAVAW [Women Against Violence Against Women], “people ripping people’s guts out.”

When she arrived in Vancouver in 1970 with a student husband and a baby, Schendlinger was refused a credit card because her husband was not working. It was irrelevant that she had a job.

Things began to change a little. There was a movement and issues that were new “and still quite embryonic, and we had kids to raise and husbands to leave and communal houses to live in.”

Some laughter mixes with the tears, in selections as different as Carol Shields’ comic story “Orange Fish” and the stunning photo-essay “The Cancer Year” by Dorothy Elias and barbara findlay [sic].

The section for the Third Decade (1998-2007) kicks off with Lana Okerlund and Meghan Bell asking “Are we feminist enough?” and the arrival of new technology, a database, even a website. Does “feminism” allow “trans-inclusive”? Was colour a factor?

The Collective rebranded with a formal change of title to Room, the name everyone had always used informally, and an effort to take more risks. “So whether we still need this women-only space, I don’t know, but we certainly need a space for that conversation.”

They found space for Anna Humphrey’s poem sequence about the Montreal Massacre, December 6, 1989, when a lone gunman killed fourteen young women, “Because you were there,” and room for “My Hero” by Ivan Coyote, whose very name evokes edginess, and for Elizabeth Bachinsky’s “Skin,” which addresses some unexpected consequences of our body-conscious culture (“What upsets Candace most about losing one hundred and seventeen pounds is that no one tells you what, exactly what, happens to your skin when you lose weight.”)

By the fourth decade (2008-2016), Rachel Thompson tells Kayi Wong about “translating intention into action,” the deliberate effort to invite diversity and explore language, exemplified in a Women of Colour issue and a translation issue. They refer to Souvankham Thammavongsa’s poem “Pregnant” which expands on the Laotian words and perceptions around childbearing.

Transgender writers and themes are now a natural part of the mix, and explorations of violence against women reflect contemporary headlines.

Such intentional reaching out to specific interests and communities risks diluting quality, but not so here. Thompson talks about maintaining “integrity yet flexibility.” While I preferred some selections to others, I found none that were not compelling.

Current managing editor Chelene Knight wants to continue “these never-ending conversations” with a wider and more diverse audience without losing sight of the founding principles.

In the predominantly urban Canadian landscape of Room, the adage to “Never judge a man until you’ve walked a mile in his moccasins” is transformed by Anishinabe poet Marie Annharte Baker to “Walk a mile in her Red High Heels.”

Baker’s stilettos are more challenging, more dangerous, more tragic, and more contemporary than those comfortable moccasins.

But this is not a contest about which gender can be the more challenging, dangerous, tragic, or contemporary. Lana Okerlund worries that “increasingly, in our world, everyone’s just talking to themselves and the people who already believe them.”

Apparently after all these years they still need to convince some potential readers that, as Mary Schendlinger proclaims, “This is not Chick Lit.” Readers of His Story beware.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. Recently she wrote the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola. She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website: https://sites.google.com/site/phyllisreeve/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster