#81 Portraits of Fenwick Lansdowne

J. Fenwick Lansdowne

by Tristram Lansdowne (editor)

Portland, OR: Pomegranate Communications, 2014

US $65.00 / 9780764966705

Reviewed by Briony Penn

First published Feb. 7, 2017

*

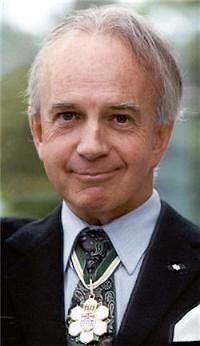

A fixture of Victoria’s artistic, cultural, and natural communities for five decades, James Fenwick Lansdowne (1937-2008) is now the subject of a book edited by his son Tristram, featuring seven essays and more than 160 illustrations.

A fixture of Victoria’s artistic, cultural, and natural communities for five decades, James Fenwick Lansdowne (1937-2008) is now the subject of a book edited by his son Tristram, featuring seven essays and more than 160 illustrations.

Reviewer Briony Penn, who knew and interviewed Lansdowne in the 1980s, reviews J. Fenwick Lansdowne and intersperses her assessment with her own recollections and quotations from the celebrated artist — Ed.

*

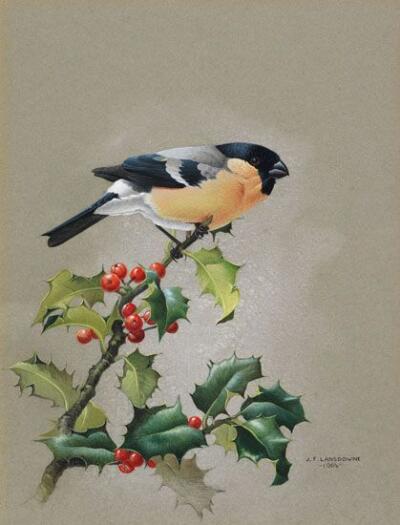

When I was growing up in Victoria, two prints that I loved hung in my room; one was of a hare by Albrecht Dürer, the other was of juncos by Fenwick Lansdowne. Both are exquisite, gentle watercolour paintings of small creatures. I had a vague notion that Dürer belonged to the Germans and their rural landscape, but a strong sense that the juncos and Lansdowne were quintessentially Victorian.

Juncos are the small, dark-headed birds with white tail feathers that flash around feed tables during our mild west coast winters. Because the two pictures hung side by side, I thought the artists must be compatriots of spirit. Two gentle men had painted the best of their places. Surely that was the way to grace — for Lansdowne has indeed been graced.

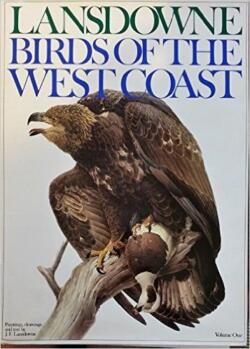

By 1977, Fenwick — pronounced with a silent w and shortened to Fen for all his friends and family — Lansdowne, was already a household name in Canada. He and his paintings had been on the cover of Maclean’s Magazine, he had been appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada, and his books Birds of the Northern Forest, Birds of the Eastern Forest (2 Vols), and Birds of the West Coast (2 Vols) had all been best sellers across Canada.

His forty-one paintings for Rails of the World, commissioned by the Smithsonian Institute, which took him ten years to complete, were heralded throughout the scientific world. His paintings were regularly chosen as gifts to royalty and hung in galleries from New York to London, and his prints hung on the walls of my parents’ and their friends’ houses, in hotel rooms, and in municipal halls, and his books seemed to be on every coffee table.

Until his death in 2008, Fen was our own little piece of royalty in this corner of the colonies that still cultivated the peculiar traits of the English: a strong Victorian artist-naturalist tradition, a dose of eccentricity, a quiet modesty, and a love of the outdoors with a scholarly bent.

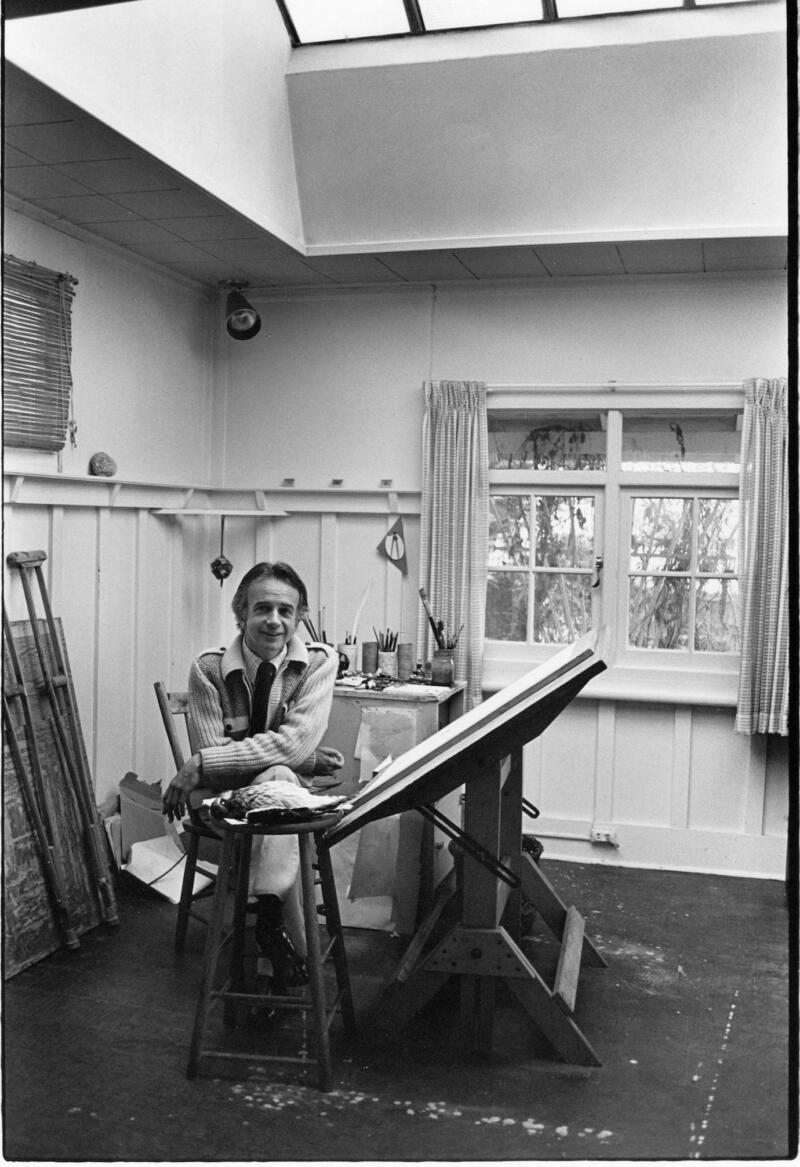

Interested in his life and career, in the 1980s I arranged for an interview with Fen. His home, where we met for tea, was packed with books, paintings, and the quiet rhythm of teatime devoid of any intrusions from the electronic age. He was dressed for the interview in tweeds and an elegant tie.

He admitted that he belonged back in the late nineteenth century, in the Golden Age of the naturalist-artist-gentleman tradition. “I am a little tweedy sort of guy, who loves birds and books but doesn’t want to rough it.”

Victoria has changed so much since then that these traits are barely discernible now amongst the new waves of impassioned tree huggers, high-powered bird-watchers, rugged wilderness enthusiasts, and big-canvas activist wildlife painters.

*

Fen Lansdowne has finally found his way back into our shelves and coffee tables after a quarter century hiatus with this comprehensive overview of his life, J. Fenwick Lansdowne, edited by his son Tristram and published in 2014 by Pomegranate Communications in Portland. The book contains forewords by Tristram and by Graeme Gibson, and essays by Tristram, Robert McCracken Peck, Robert Genn, Patricia Feheley, Nicholas Tuele, and Tony Angell.

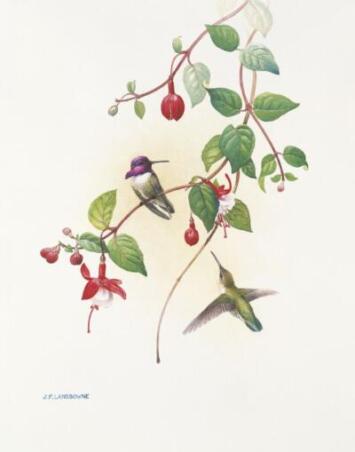

Fen’s fans can be assured that they are getting the best of his paintings from his seven books, including the rarely-seen Rails of the World and Rare Birds of China, and a body of unpublished work from the two decades before his death.

For a new audience, this is an excellent introduction to the artist and to the art that gained him admirers from royalty to radicals.

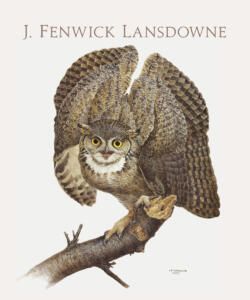

The back cover of J. Fenwick Lansdowne describes him as “a humble man, yet with a commanding presence,” while the front cover offers a hint of what is to come with Lansdowne’s painting of a (commanding) Great Horned Owl staring defiantly at the reader from a branch, mantled wings framing yellow gamboge eyes.

Delving deeper into the book, readers will find Fen’s humbler qualities manifest in his pencil sketches drawn from life that capture, according to contributor Robert McCracken Peck — a natural history consultant to David Attenborough — “the beauty and, if possible, the spirit of his subjects.”

Peck’s excellent essay, “Not another Audubon,” locates Lansdowne in the rich and colourful lineage of great naturalist painters of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including Canadian artists Allan Brooks and Ernest Thompson Seton, British artists Edward Lear and Archibald Thorburn, and Louis Agassiz Fuertes and John James Audubon in the United States.

Peck tracks Lansdowne’s long and successful art career, starting at the age of twelve when he was encouraged to paint birds by his artist mother, Edith, a watercolour artist in the Chinese tradition.

Born in Hong Kong in 1937 to British parents, Lansdowne was only ten months when he contracted polio. He thought the virus might have been in the sand he reportedly stuffed in his mouth on the beach at Deep Water Bay. His parents tried to find some cure for the disease, which took them from London to Victoria in pursuit of the newly pioneered practice of physiotherapy.

Lansdowne and his mother ended up at the Brentwood Solarium near Victoria in 1940. His father, in the meantime, had returned to Shanghai with his company, only to be interned there until after the war. During the next five years of getting treatment for a collapsed lung and atrophied muscle in his legs, Lansdowne and his mother lived around the Mill Bay and Cowichan areas.

In the 1940s, Mill Bay was an exceptionally rich place for wildlife, with seabirds over-wintering in huge numbers in the bay and songbirds moving through the mixed forests of maple, oak and fir, as Fen told me. “I remember every bird encounter at that age, the hummingbird nest outside my window, the house wrens, the pileated woodpecker and the ruby-crowned kinglet we found frozen in the woodshed.”

Confined to crutches with post polio syndrome, Fen was educated at St. Michaels University School and Victoria High School but, as he told me, “I was unteachable. I was an autodidact and all I wanted to do was draw.”

A friend’s mother suggested that he go and see Clifford Carl, the director of the Provincial Museum. Carl, along with Charles Guiguet, the museum ornithologist, and Frank Beebe, the technician/artist, opened up the collection to this budding young artist:

I went to see Guiguet weekly and he would lend me birds from the collection. Beebe was an excellent naturalist as well as an artist and he taught me everything he knew about specimen preparation and illustration. Who today could just walk into a collection and take the specimens home to draw? They even employed me for two summers to prepare specimens, although I mostly just drew. I owe a lot to these men.

At the time, the bible of Canadian bird books was Percy Taverner’s Birds of Canada, with illustrations by Allan Brooks. “I can still remember Brooks’s junco and jay on the page,” recalled Fen.

I asked him who his other influences were and he told me, latterly, Louis Agassiz Fuertes and Archibald Thorburn. “What about Audubon?” I asked, since he is commonly described as Audubon’s successor, and since he had Audubon prints hanging in his house. “I found his paintings very dark as a child and they weren’t as familiar as Brooks’s,” he told me.

While finishing his last year at Victoria High School, Lansdowne started to hone his skill to the admiration of his classmates and teachers. Spotting Lansdowne’s talent, Mr. Heywood, the school counsellor, sent off some paintings to a friend in Toronto in the publishing business who showed them in turn to John A. Livingston, executive director of the National Audubon Society of Canada.

Livingston, a well-known naturalist and radio broadcaster, took them to the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), and still only nineteen, Lansdowne’s career was launched: the ROM offered him a public exhibition with forty watercolours of west coast birds.

He then made it into Maclean’s magazine in 1957 with big colour insert spreads of his paintings. He never looked back, enjoying not one but two patronages: Livingston and businessman-agent Budd Feheley, whose daughter Patricia brings to life, in her essay here, the long relationship between the two men through letters and fruitful collaboration on publishing projects.

Robert Genn, artist and naturalist, adds a perceptive essay on their childhood friendship and subsequent road trips through the province and down into the desert states. Genn captures the vital characters they meet along the way, feathered and otherwise, and evokes the playful pedantry of Fen in his early years in Oak Bay, when he sported his pipe and binoculars. Fen’s trademark olde-world cravat came later.

Genn also describes the serious side of Fen, the naturalist who witnessed change: someone who was “disdainful of ugliness and destruction.” “Fen so much lamented the decline of some species and the extinction of others. It was to become one of the major causes of his life. ‘We should always have such things,’ he said.”

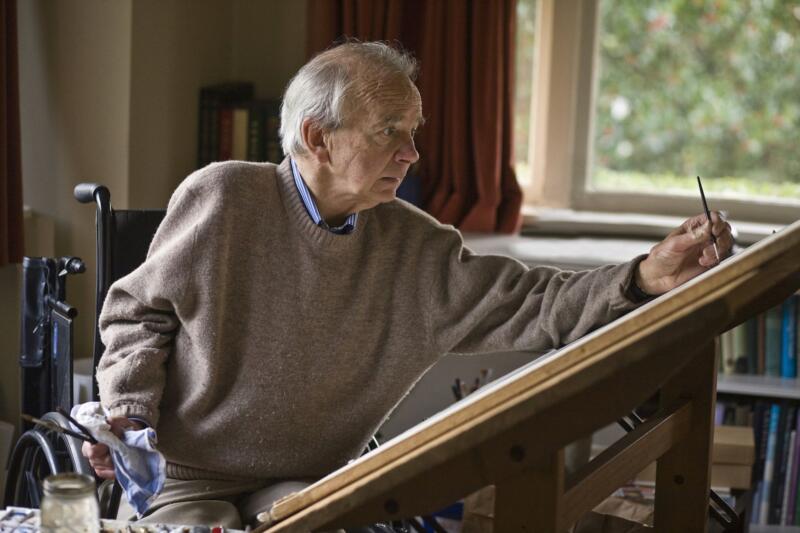

One of Fen’s later friendships was with the Seattle sculptor-author Tony Angell, who provides the final essay of the book. Best known for his books on crows and ravens, Angell found a surprising friendship in Fen, whom he describes as “the most articulate, quiet man I have ever known.” He also notes Fen’s rare ability to capture “the fullness of his subjects, augmented by his sense of touch.” Fen captured the life of the subject in his pencil sketches and then used skins from museums to render the plumage accurately.

An artistic purist, Fen disdained photos with the same passion as ugliness. Photos might “interrupt the flow of his sensory, emotional and intellectual response to the subject.”

Of Fen’s handling of a Northern Shrike, Angell writes, “he cradled the bird in his open right hand, and with the other hand — the painting hand — he opened and closed each wing, traced the shape of the bird’s beak and stroked the feathers across its brow and down over the back and flanks.” In these ways every bird of Lansdowne’s was “felt” as well as seen in his bird portraits.

The warm and intimate portraits of Lansdowne are celebrated in the Preface by his son Tristram, who describes his feelings as “complicated” when asked to write about his father. Also an artist, Tristram describes Fen as a “private person,” “so singularly dedicated to his work that it cannot be fully extricated from his personality.”

The only essayist who disappoints is Nicholas Tuele, former Chief Curator of the Victoria Art Gallery, who contributes a surprisingly dull account of a marvellous exhibition of Fen’s Rare Birds of China, which he curated in 1998. In his rambles into symbolic bird iconography, Tuele fails to address an obvious question: Why did it take the Victoria Art Gallery so long to have a public exhibition of Lansdownes?

The ROM was showing Lansdownes in 1956, the Vancouver Art Gallery mounted a one-man show in 1981, but it took Victoria Art Gallery – in his hometown — 42 years to follow suit.

Tuele was curator on much of that watch and might have provided some insight into why the institutional segment of the Victoria art community was so slow to recognize this locally treasured and internationally renowned artist of wildlife.

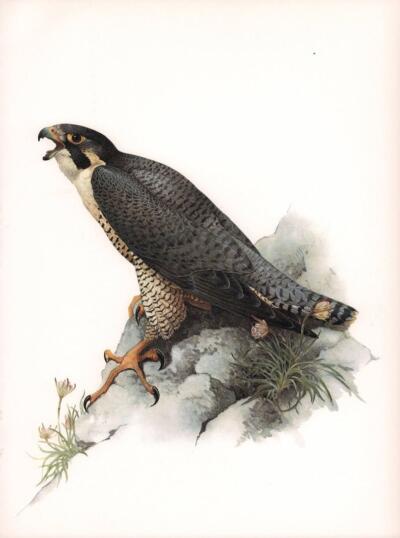

Fen’s bird portraits, of course, are the greatest value of this book. Here is a fine selection in all their plumaged complexity. The last image in the book is Fen’s final painting, of a peregrine falcon that is looking ambivalently over its shoulder at the reader. Is it prey or predator? This is a good question for a world that, having nearly pushed this bird into extinction, can also produce the likes of Fenwick Lansdowne to peer into its soul.

*

A fifth-generation Vancouver Islander, Briony Penn was born in Saanich in 1960 and educated in Victoria; at UBC, where she studied geography and anthropology; and the University of Edinburgh, where she received her Ph.D in geography in 1988. She is known for her long-running Wild Side column for Monday Magazine (Victoria), A Year on the Wild Side (TouchWood, 1997, reprinted 2019); Islands in the Salish Sea: A Community Atlas (TouchWood 2005, foreword and contributor), and The Real Thing: The Natural History of Ian McTaggart Cowan (Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2015), which won the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize and was shortlisted for the Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize at the 2016 BC Book Prizes. She lives and works on Salt Spring Island. Editor’s note: Briony Penn has also reviewed a book by Russell Cannings & Richard Cannings for The British Columbia Review. Her book A Year on the Wild Side is reviewed by Luanne Armstrong and her books Stories from the Magic Canoe of Wa’xaid and Following the Good River: The Life and Times of Wa’xaid (both with Cecil Paul) are reviewed by Charles Menzies.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#81 Portraits of Fenwick Lansdowne”

Comments are closed.