The marriage trap

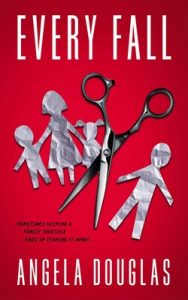

Every Fall

by Angela Douglas

Toronto: Rising Action, 2025

$25.99/9781998076819

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

As I was reading Every Fall, the debut novel by Okanagan writer Angela Douglas, I was irresistibly visited with this remixed maxim: a mother with postpartum depression needs a boorish cop husband like a fish needs a bicycle.

Bree is an overwhelmed mother who learns that she is pregnant again. After witnessing a particularly blood-splattering death in a grocery store, Bree and her husband, Jake, decide to relocate from their apartment in a “cesspool” to a more suburban neighbourhood where a backyard is possible. Bree regards the birth of her son, Riley, as traumatic, and is fearful of a second birth. The novel switches between Bree’s point of view and Jake’s, both written in first-person, which means the reader often knows more than the characters themselves do. Periodically, I fought the urge to shout, “Just learn how to communicate! Read a book by the Gottmans!”

Although Jake is sworn to serve ten years in East Bernheim, “affectionately known to locals as Burner,” he decides it is imperative to relocate after the Scaggs, well-known criminals, threaten Jake by implying they know exactly where Jake and Bree live. Jake does not tell Bree about the threat, but agrees that they need to relocate to a bigger place. The house Bree and Jake move into is perpetually cold, directly beside a women’s shelter, and, rumour has it, the setting of at least one death. Tenants don’t stay for long. Adding further insult to injury? The house isn’t dog-friendly. Bree, who has had her ten-year-old pug, Lottie, for longer than she’s been married to Jake, is distraught when she has to part with Lottie. Jake isn’t particularly sympathetic. I’m of the unsubstantiated theory that when a person is indifferent to dogs, they’re probably an unsavoury character I wouldn’t want to be stuck in an elevator with.

Bree begins seeing a ghost. Baby bottles are lined up in ways she doesn’t remember. It’s creepy! The ghost is, like Bree, also a pregnant woman. Is Bree losing her mind, or is the apparition real and trying to communicate? After a personal loss, Jake lashes out at Bree. He never calls their second child, Ivy, by name, but only as “the baby.” Instead of sharing his feelings—that would be antithetical to his character—he enjoys the flirtatious company of Amber Doyle, a constable who seems to genuinely understand him—or at least, what his cock desires. A former quasi-teetotaler, Jake relies on alcohol to assuage his despair, which Bree observes but does not comment on, for fear of his retaliation.

Jake embodies toxic masculinity, a seeming prerequisite for his career. He fears the implications of what it means to see a psychologist and worries it will cost him his reputation or, worse, his job. For Jake and the other cops, there is nothing worse than being perceived as a pussy—perhaps this is why there are so few women on staff. Funnily enough, when Jake hears a co-worker use the term pussy as a pejorative for a weak, feelings-oriented man, Jake balks—hypocrisy at its finest. It is also notable that for all his grandstanding, stereotypical machismo, he has no qualms about his best friend being a gay man, which helps add dimension to what could otherwise be one-dimensional.

It becomes increasingly difficult to imagine that Bree and Jake were ever in love with each other. In a thriller populated with criminals and, possibly, a ghost, the scariest thing in this book is their marriage. It’s not until I was more than two thirds of the way through the novel that Bree and Jake’s romantic origin story is revealed, and it is both utterly believable and totally inconceivable that their animosity, distance, and mutual unhappiness was ever sufficiently amazing as to result in prematurely headlong commitment after the fourth date. Apparently, it’s frighteningly possible to find yourself wedded to someone on the basis of blue eyes and a strong jawline. Jake’s behavior is such that their firstborn, Riley, becomes scared of him.

Bree’s maternal ambivalence is depicted with appropriate nuance for such complex subject matter that might scare less ambitious authors. Bree loves her children immensely, but also desperately fears an official diagnosis of postpartum depression in case it is used against her. Bree’s own relationship with her mother is strained—her mother is well-intentioned but consistently overbearing, thoroughly unimpressed with Jake (same as me), and judgmental. Her sister, Paige, is a reliable confidante but lives far away. At one point, Jake notices that Paige has cleaned the house during a visit and jokingly muses, to himself, that he married the wrong sister. At times, it seems that Bree’s largest personality flaw, from Jake’s perspective, is messiness and existing in his vicinity.

She later befriends another cop’s wife, Tammy, who Jake initially tells Bree to avoid. Thankfully, Bree doesn’t listen. Tammy is a much needed beacon of nonchalant wisdom, experience, and reassurance—exactly what Bree and the reader need. It’s gauche to rate characters based on that nebulous subjectivity otherwise known as likability, but Tammy is the most likeable character in the novel by a long shot, with Lottie the pug coming in second.

Every Fall is often a grisly, emotionally draining read where everyone is doing their best, with the caveat that unfortunately, sometimes one’s best still harms the people you love most. I appreciated the care given in depicting the complexities of postpartum depression, ADHD, toxic masculinity, and the sad reality that, more often than not, a heterosexual marriage embedded in the trappings of suburbia, is deeply fraught and unhappy. Cuddle your dog, call a friend, confirm the whereabouts of your child—this novel that will make you scrutinize any of the ostensible positives of a long-term commitment.

*

Originally from East Vancouver, Jessica Poon is a writer, former line cook, and pianist of dubious merit who recently returned to BC after completing a MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. [Editor’s note: Jessica interviewed Sheung-King, and recently reviewed books by Holly Brickley, Alastair McAlpine, Jack Wang, Bal Khabra, Christopher Cheung, Anne Hawk, Pat Dobie, and Giana Darling for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster