Searching for a better life

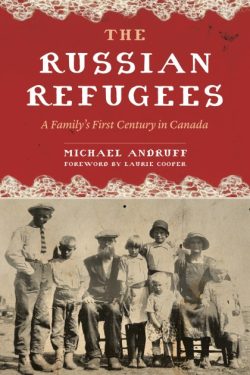

The Russian Refugees: A Family’s First Century in Canada

by Michael Andruff

Vancouver: Heritage House, 2022

$26.95 / 9781772034196

Reviewed by Duff Sutherland

*

In The Russian Refugees: A Family’s First Century in Canada, the late Michael Andruff (who passed away in December 2023) chronicles the story of three generations of his family in Canada. In the early 1900s, Andruff’s great grandfather, Gregory Andriev, moved his family from Staraya, north of Moscow, to the Amur Valley in Siberia. The Russian government’s efforts to colonize the eastern part of the empire in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese war (1904-05) through offers of land to peasants led to the move. The Andrievs, who were part of a community of “Old Believers” of the Russian Orthodox Church, valued land ownership and religious freedom. In the aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution, the family fled to Harbin, China, along with 16,000 other Russians. In 1923, with the support of the colonization department of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Russian Red Cross, and the Russian Refugee Relief Society of America (RRRSA), the Canadian government granted visas to a chosen group of twenty-one Russian families (116 refugees) to settle in Canada.

Initially the group settled in a colony called Homeglen south of Edmonton. By 1929, however, a group of the Old Believer families, including the Andrievs (Canadian officials and family members anglicized the family name as Andreeff, then Andruff), started homesteads near present-day Gage, Alberta. Andruff points out that the Canadian government took the land for settlers from the Beaver Indian Reserve Number 152. On these lands, Andruff’s father, Nikifor (“Mike”) grew up on the farm of his parents, Phillip, and Elena, and their ten children.

After 1945, socio-economic forces that transformed Canada had a profound impact on subsequent Andruff generations. Andruff’s father and mother, Mike, and Natalie (Sidoroff), left the farm to work and raise their family in expanding resource and, later, service industries in Alberta and British Columbia. Mike worked as welder in the construction of Macmillan Bloedel’s kraft mill in Port Alberni. Later, he operated a machine shop in northern Alberta. In 1955, a serious accident left Mike permanently disabled. After his accident, Mike worked for forest industry companies in Port Alberni, for a manufacturer in North Vancouver, and as manager and labourer for a family real estate investment club. Founded in 1966, the investment club relied on the skills and “sweat equity” of Mike and Natalie to renovate, sell, and manage properties in New Westminster, Surrey, and Castlegar. The investment club had success but eventually folded partly due to the “management by chaos” of Mike and Natalie. In the 1970s and 1980s, Mike and Natalie worked as building managers for a Travel Lodge, and for apartment buildings in Surrey and Vancouver.

As was common during the era, alcoholism and domestic violence blighted the lives of Andruff’s parents and their three children. Andruff describes a prosperous family life in the 1950s and 1960s that included a comfortable home with a television, camping and fishing trips, father-son Scouts banquets, and family picnics and reunions. He also describes regular, violent fights between Mike and Natalie, Mike’s beatings of Natalie and his children, child neglect, and ongoing financial problems. Andruff notes that his younger sister, Laurie, experienced the worst of his parents’ bouts of drinking, violence, and “depravity.” Although not detailed, Andruff’s account of his family life during these years points to a darker side of Canada’s postwar economic expansion.

Andruff describes his own life experiences and those of his daughter, Thea, in the latter part of the book. Andruff escaped the violence and alcoholism of his home through going to work, junior hockey, university, and marriage. By the 1970s, the expansion of university education and a strong work ethic combined to help Andruff to a University of British Columbia commerce degree and CGA designation. Andruff went on to work for several large British Columbia forest industry corporations for almost two decades.

In the early 1990s, Andruff began a further career as a real estate agent in Vancouver. He eventually owned his own company. His wife Claire (Brewster) raised their three children and then joined her husband as a realtor. Andruff describes a prosperous family life as the Vancouver real estate market exploded from the late 1980s on. His family enjoyed sports and the social life of the Arbutus Club, summers at the family property at Crescent Beach, a spacious house in Dunbar, and trips across Canada and around the world. With a commitment to family, Claire, and Michael devoted attention to each other, to their children and grandchildren, and to the care of Mike and Natalie in their final years. Andruff’s daughter, Thea, attended the Point Grey Mini School, took an extended gap year to travel, and went on to university where she completed a graduate degree, taught at Douglas college, and began to raise her own family. Andruff is proud of his own successes and those of his family since their arrival in Canada as refugees in the 1920s. He is not boastful. Rather, Andruff’s goal is to demonstrate the struggles and achievements of refugees.

The Russian Refugees is a compelling story of three generations of a refugee family in Canada. Andruff sensitively describes the challenges of his parents, with limited education and resources, to make the best of the opportunities of a growing Canadian economy from the 1950s on. His father’s traumatic accident contributed to a family life of violence, and addiction. Andruff himself succeeded as he fully assimilated, achieved education and training, and took advantage of the increasing opportunities and prosperity of Canada from the 1970s on. Andruff recognizes that Canada’s selective immigration system favoured his family in the 1920s. He also describes how his family’s initial settlement in Alberta was part of a process of settler colonialism that displaced Indigenous peoples from their lands. With The Russian Refugees, Andruff desires to educate Canadians about past and present refugee experiences. He also offers information and encouragement for private, individual, and group sponsorship of refugees. This social message adds to the impact of an impressive, and honest work of family history. Andruff’s work is well worth reading.

From left, Kay, Mike, Laurie, Natalie, and Michael Jr. Courtesy Andruff Family Album

*

Duff Sutherland has taught undergraduate history courses for over twenty-five years. At Selkirk College at Castlegar he teaches history of the West Kootenay. As well as many book reviews in The Ormsby Review, BC Studies, and elsewhere, Duff has published articles on Newfoundland labour history and the relations between settlers and Indigenous peoples in the West Kootenay. [Editor’s Note: Duff Sutherland has reviewed books by Jean Barman and Kyle Kusch for The British Columbia Review.)

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster