A departure into maritime history

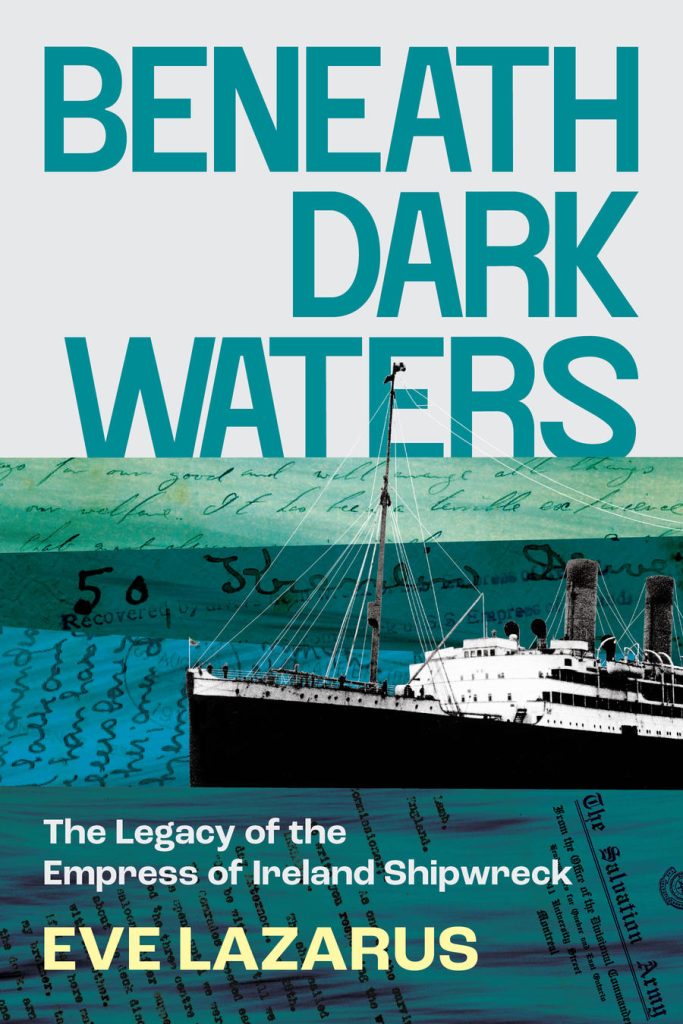

Beneath Dark Waters: The Legacy of the Empress of Ireland Shipwreck

by Eve Lazarus

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2025

$26.95 / 9781551529738

Reviewed by Ian Kennedy

*

Most readers will, I suspect, be familiar with the maritime tragedies of the RMS Titanic and the RMS Lusitania. Few will likely know much about the sinking of the RMS Empress of Ireland, the worst peacetime maritime disaster in Canadian history. Author and researcher Eve Lazarus sets out to rectify this omission, as well as challenge some of the long held myths about the sinking, in her latest book Beneath Dark Waters: The Legacy of the Empress of Ireland Shipwreck. The book delves into the tragedy that cost 1,012 passengers and crew their lives in May 1914.

Lazarus researched hundreds of historic documents related to the disaster, retrieved personal letters from the families of those who had been on the ship, and investigated the reports of the inquiries held into the catastrophe. Her extensive efforts enabled her to write a comprehensive account of the tragedy and of the lives of those involved. This is Lazarus’ eleventh book.

On May 28, 1914, in fine weather, the Canadian Pacific’s Empress of Ireland set sail from Quebec City with 1056 passengers and 423 crew bound for Liverpool, England on her 192nd Atlantic crossing. At 1.30 am off Rimouski at the widest part of the St. Lawrence, the ship encountered fog and shortly after the bridge sighted the Norwegian coal carrier Storstead, making her way up river. Somehow the ships collided, with the freighter smashing a gaping hole in the side of the passenger ship. Huge volumes of water poured into the Empress, sinking her in fourteen minutes. The crew only managed to launch four of the forty lifeboats on the Empress leaving most passengers and crew to take their chances in the frigid waters. In the end, 1,012 of them lost their lives.

Lazarus outlines the stories of many of the passengers, their lives in Canada, and their reasons for being on the ship at the time of the accident. She also follows the lives of some of the survivors, pointing out the double tragedy that a number of men who survived, then signed up to serve in the First World War, only to die in the trenches of the Western Front.

The book displays many photographs scoured from a wide variety of sources, many taken by Lazarus herself. A comprehensive appendix lists all of the passengers and crew who survived and those who perished. The ship had eight decks and the First-Class passengers on the upper decks proportionately suffered the fewest losses, while those in Third class or steerage on the lower decks, suffered the highest percentage of deaths with 578 of 714 being lost.

Lazarus questions why this harrowing calamity, with 836 passengers perishing, is not so well known as the sinkings of the Titanic — with 832 passengers lost — or the Lusitania — with 788 passengers lost — and suggests that while the Titanic carried “…big names from the New York social register, the Empress of Ireland was a comfortable workhorse filled with ordinary Canadians.” Given that the population of Canada at the time of the accident numbered around 18 million, the loss of 836 of its citizens resonated right across the country, making this a very Canadian tragedy. Also, the Empress was not on its maiden voyage, and within months of the sinking, the First World War claimed the headlines.

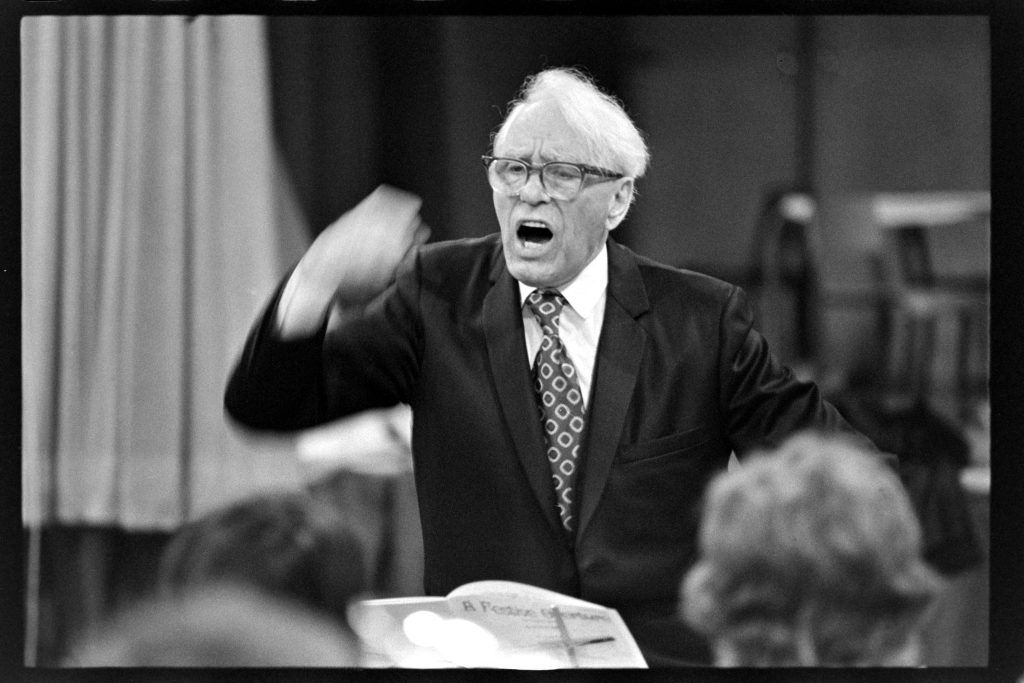

The ship carried a contingent of 161 Salvation Army faithful on their way to a Congress in England, including the Delamont family from Moose Jaw. Eldest son Leonard died in the shipwreck and the rest of the family later moved to Vancouver where another son, Arthur, formed and led the world-famous Kitsilano Boys’ Band. This gave young musicians such as billionaire Jimmy Pattison and band leader Dal Richards as well as many other young people, their start in the music world. The Governor General awarded Arthur Delamont the Order of Canada and a park in Vancouver bears his name.

Lazarus does much to root out and correct the ‘fake news’ articles written about the sinking, and the ‘racism’ against the Norwegian captain and his crew. Newspaper reporters rushed to Quebec following the tragedy seeking personal accounts from the still shocked passengers. The reporters then embellished and sensationalized those accounts playing fast and loose with the facts, distorting the story of the tragedy. Added to this, those reporters immediately implied, without evidence, that undoubtedly the ‘foreign’ Norwegian ship had caused the catastrophe. One headline heralded: “Big liner rammed and Sent to Bottom by Collier.”

At the nine-day long Inquiry that took place in Quebec City in June 1914, the Norwegians suffered from language disadvantages “…and were either supplied with an interpreter or, if one wasn’t available, were forced to plod along in broken English.” In the end, the Norwegian second officer, Alfred Toftenes, who had been in charge of the bridge of the Storstead at the time of the collision, took the blame. The official finding of the Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry found that: “Mr. Toftenes was wrong and negligent in keeping the navigation of the vessel in his own hands, and in failing to call the captain when he saw the fog coming up.”

Lazarus details the poignant stories of unselfishness, heroism, and kindness that accompanied, and followed, the sinking. Once the people of Rimouski and Quebec City became aware of the accident, they stepped up to clothe, feed, and house the unfortunate survivors in true Canadian fashion.

As a point of style, the author’s constant incursion into the narrative often seems unnecessary. Writing Style Guidelines once insisted that authors avoid using the first-person voice when writing non-fiction books. This, however, appears to have gone by the board and authors can now choose to use the first-person voice or not. Call me a curmudgeon, but I still find using the first-person voice in non-fiction writing irritating. For example, on p. 39 Lazarus writes: “I contacted the CPR’s archives to see if they had a train manifest… but they do not exist.” Write: “The CPR archives do not have train manifests in its archives.” Or, on p. 259 “… I’ll be flying to Quebec City tomorrow, but first I’m stopping over in Edmonton and making a two-hour drive to Stettler, Alberta.” Not needed!

This is an intriguing story and Lazarus is to be commended for her thorough research into this tragic Canadian event. It is worth noting that this tragedy is also the subject of some fifteen other non-fiction and fiction works going back to 1914 and one wonders what prompted Lazarus to write yet another.

*

Ian J.M. Kennedy of Comox was the recipient of the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize at the 2024 BC and Yukon Book Prizes for his book The Best Loved Boat: The Princess Maquinna. Born in County Donegal, Ireland, came to Canada in 1954 where he attended Burnaby North High School and earned a B.A. from UBC. Later he did post-graduate work at Queen’s University, Belfast, and on his return to Canada taught geography and history at Steveston Secondary School for thirty years. Following his retirement in 1999, he moved to Comox and became a rugby journalist, travelling the world and writing about a game he never played very well. Widely published in many magazines, his journalism also includes numerous articles about history, travel, motorcycling, cottage living, and pubs. His books include his recent The Best Loved Boat: The Princess Maquinna, Guide to the Neighbourhood Pubs of the Lower Mainland (Gordon Soules, 1982), The Pick of the Pubs of B.C. (Heritage House, 1986), Sunny Sandy Savary: A History of Savary Island 1792-1992 (Kennell, 1992), The Life and Times of Joe McPhee, Courtenay’s Founding Father (Kennell, 2010), and Tofino and Clayoquot Sound: A History (Harbour, 2014), co-authored with Margaret Horsfield. [Editor’s note: Ian Kennedy has also reviewed books by Chris Brauer, Patrick Taylor, Jon Stott, Glen Mofford, Glen Cowley, and Peter McMullan for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster