Then and now: a palimpsest

A Place Called Cumberland

by Rhonda Bailey (ed.) and The Cumberland Museum and Archives

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2024

$25 / 9781773272511

Reviewed by Loÿs Maingon

*

As Rosslyn Shipp, the Executive Director of The Cumberland Museum and Archives notes in her introduction to this short, well-illustrated volume: “A Place Called Cumberland is a journey through personal accounts, dialogues and a palimpsest of memories, all representing different experiences and times of discovery.”It brings together the work of twelve BC contributing writers who at some point in their careers have had an association with Cumberland.

Some people affectionately refer to it as “the Republic of Cumberland.” “The Village of Cumberland,” sometimes referred to in this volume as “the City of Cumberland,” has played an important, if outsized, role in the history of British Columbia. As contributor Andrew Findlay points out: “to understand where Cumberland is today, you need to understand where Cumberland was yesterday.” Unlike its neighbours in Comox who have largely destroyed their heritage, Cumberland has cultivated its historical heritage and, as a consequence, is better placed today to address future challenges. As the village has literally risen from the ashes of its coal-mining past which came to an end in the mid-sixties, it has renewed itself over the past two decades when it became a haven for creative, alternative, and progressive minds, and has been reinvigorated by the environmental movement and the community-building work of The Cumberland Forest Society.

Waterworks in July 1897. Lewis Mounce, lumberman and future first mayor of Cumberland, is standing third from the right in the back row beside two ladies in hats. Euphemia, Irene, and Leland Mounce are also present. Photo courtesy Daryl Calnan

In that sense, with one of the province’s youngest demographics, like a velum scraped for re-writing anew, Cumberland has become a palimpsest for new generations to rewrite. Generations inherit their progenitors’ suppressed anxieties and aspirations. They reiterate the best of their predecessors’ aspirations, only if they know them. Without a clear memory of that history, they inevitably repeat some errors, and yet inexorably move the dial to improvements in social justice.

That is an important point to bear in mind when reading these journeys in an age of climate change. Increasingly, science reports remind us that the most important key to addressing and surviving climate change lies in social justice.1 Climate change is not just a factor of atmospheric carbon concentrations that politicians and corporate mouthpieces tell us will be solved by a miraculous “net zero.” (In fact, approaching climate change that way has met with the failure to address it for the last thirty-five years, possibly by design.) Beyond its technical understanding in atmospheric chemistry, climate change is really just an expression of a failing capitalist economy’s excessive reliance on endless cheap energy to mine the planet and its inhabitants. Even if we were to solve the carbon problem, the continued destruction of biodiversity and the biological processes that sustain life on earth would continue to drive climate change. Climate change is endless, if our social and ecological relationships remain tied to a capitalist economy and its assumptions remain unchanged. In Cumberland, those assumptions have been challenged for the past two centuries, and they continue to be challenged.

Cumberland Museum & Archives Collection

Some have suggested that transformative change appears to be coming with the very millennials and Gen Z’ers who have settled in Cumberland over the past twenty years.2These generations have grown weary of elites and the old top-down, left-right centralized democracy that has sustained capitalism over the past three centuries. They seek a more direct involvement in community democracy by cultivating a greater sense of personal relationships in their communities, and demand greater social justice in all aspects of their lives. However awkward the woke movement may seem to previous generations, it is the bottom-up backbone of social change that will get us out of the planetary crisis we have created.

Tracy Skuse initiates the journey with “Circa 1999” with an exploration of relationships to place, as her biography indicates “in an age of climate change.” She provides readers with an informative insight of a young woman’s predicament in twenty-first century rural BC, and how in many ways it repeats the experience of nineteenth-century miners’ wives. It presents a continuity, and also a change, begging the question “where do you fit in?”

Where people fit in – or don’t – is addressed by Lynne Bowen in “Birds of a passage” which traces the history and continuity of families of Italian miners who were brought to Cumberland by James Dunsmuir, because they were known “strike-breakers.” Then over time they too evolved and came to be integrated in the community as they built families. Many of them, like the Lewis family, remain cornerstones of the Comox Valley. And pointedly, the obligations that come with raising families shift our relationships to people and place, so as Lynne Bowen points out: “Italians’ love of la familia was mainly responsible for ending the Italian connection to strikebreaking.”

The question of fitting in is as central to the history of Cumberland, as it is to the history of colonialism in Canada. With “Tides of Time,” an exploration into the reporting and inquest into the great Trent River train disaster, Kim Bannerman explores the system of erasure that discriminated against Asians, even in death. She recounts the collapse of the 100ft trestle bridge which caused a train to plunge down into the canyon and resulted in the death of six people, four Caucasians who were named in all reports, and two Asians who for long remained anonymous, “simply lumped together in a category based on race.” This raises the question of what is really meant by “the sympathies of the entire community.” Were the two Japanese men K. Nanko and Osana not part of the community? How do we really define “community”? There are always scapegoats, needed to bind community. As Bannerman concludes: “by discussing the darkest acts of Cumberland’s diverse history we can learn to create a more welcoming and resilient future, where the contributions of each individual are equally celebrated and remembered, regardless of class, status, gender, or race.”

The question of inclusivity raised by Bannerman dovetails into Rod Mickleburgh’s essay “Joe Naylor: Worker’s Rights and a Better World,” which anchors the entire collection and draws heavily from Roger Stonebanks’ memorable 1997 account “Joe Naylor: A Man of Principle.” Mickleburgh does an excellent job reviewing who Joe Naylor, BC’s 1917 president of the BC Federation of Labour was. Like Stonebanks before him, Mickleburgh makes the case that Joe Naylor was historically overshadowed by his friend Ginger Goodwin, but deserves more attention as a central figure in BC history. Today Naylor remains more relevant than ever as the tenacious spirit that best epitomizes progressive Cumberland of the past two decades. As Stonebanks famously pointed out, Naylor was the most radical union leader on Vancouver Island. It is its most radical elements that continue to make Cumberland interesting today, in a province smothered by golf courses and shopping malls. Unlike many union leaders he opposed racism and defended Asian miners. He understood that it was not people who were to be opposed, but the inherent intolerance of “this damnable system” and that capitalism endangers humanity and needs to be dismantled. Mickleburgh makes a good case of pointing out that after the great mining strike of 1912-1914, (which is normally rightly referred to as the “Coal War of 1912-1914”) Naylor remained a social outsider who found unions after 1920 “too compliant.” Naylor would be quite attuned with today’s Gen Z’s contempt for top-down centralized democracy, which is rarely democratic.

Dave Flawse in “Springing the Trap: The Tale of the Flying Dutchman”, takes us to Union Bay’s 1913 General Store robbery and shootout which put an end to one of BC’s few modern pirates, Henry Ferguson, who lived and operated out of Lasqueti Island. The conclusion of the tale bears some surprises that put in question the entire sense of law and order in BC at the beginning of the twentieth century, and perhaps even today. In practice, the divide between thuggishness and respectability is thin in BC. Just as an embezzling real estate agent, the future Sir Arthur Currie, led the largest deployment ever of the Canadian militia in what remains a violent expression of respectable thuggery to brutally repress the miners’ strike of 1912-1914 in Bevan, Flawse discovers that “BC Provincial Police constables were indistinguishable from the criminals they arrested.” This is a point which should not be lost on all British Columbians who witnessed, just two years ago, the RCMP’s conduct at Fairy Creek and at Wet’suwet’en. That this was conduct acceptable to BC’s ruling NDP government and the BC Appeals Court should be edifying for all British Columbians concerned with social justice. The early twentieth century was an era of ruthless class war meeting the needs of a damnable system, which still finds echoes today.

Within the characteristically difficult, and often brutal, circumstances of the 1890s to 1930s, Bevin Clempson in “One Stout-Hearted Entrepreneur” still finds it possible to celebrate the life of a remarkable woman, Diana Pickard Day Piket. Diana Piket owned and ran The Cumberland Hotel with her eventually estranged husband, and then ran a successful boarding house, “Belvoir Vila.” A successful woman entrepreneur, she would become a central figure in Cumberland’s social landscape, raising money for charitable causes. As a “farmer, then as a businesswoman, philanthropist and mother” she set out a historic precedent for the important central community-building role that independent women to this day continue to play in Cumberland culture.

So, it is no surprise that in celebrating “Cumberland Chinatown: My Hometown,” Dr. Tom L.Q. Wong takes time to celebrate “The Kindness of Mrs. Finch.” Lydia Katherine Finch, the Anglican teacher, who together with the school principal, Mr. George Apps, took time to teach Chinese children English. They gave marginalized Chinese children the tools to overcome segregation. This helped them form connections and integrate into BC’s mainstream, to move away from the ostracism in which the Chinese community found itself, “a community loathed and marginalized by dominant society.” Dr. Wong provides insights into the brutality of human beings, regardless of ethnicity, towards their fellow humans with the story of his own mother, Lee Cow. She was first sold to the wealthy Yip family in China, and then in 1923 at the age of thirteen was again sold to Dr. Wong’s father. Widowed early, with no formal education and little or no literacy, she proved extremely resourceful and industrious. She successfully raised six children through The Great Depression. Dr. Wong’s story is a story about “fitting in,” and overcoming exclusion.

Exclusion resurfaces in Dan Copeman’s short biography of Dr. Irene Mounce, one of Canada’s foremost mycologist after whom “The Red-belted conk” (Fomitopsis mounceae) is named. The name was chosen by fellow mycologists to partially atone for her professional and social exclusion as a result of her gender. Although she came from a wealthy Caucasian family, Irene Mounce was throughout her career discriminated against professionally, notwithstanding her brilliance as a plant pathologist working in Ottawa’s Department of Agriculture. In 1945, she was forced to resign because of a rule stipulating that female civil servants could not be married. Although men could marry, women were ostracized if they did the same. As the record shows, from there she slipped into oblivion.

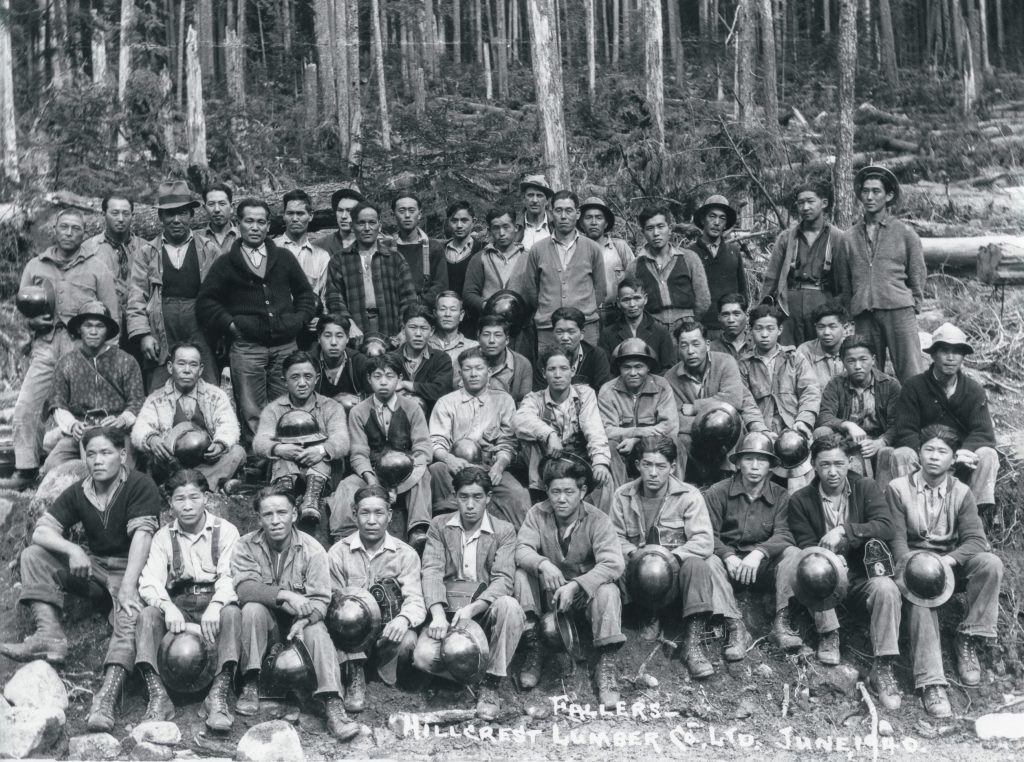

As Russell Sakauye witnesses from Toronto, in “Cumberland Chow Mein,” exclusion took a tragic turn for Japanese communities in BC. He pieces together an account of the successes of the Ogaki logging family in Cumberland before the Second World War, thanks to archival material gathered by the University of Victoria’s “Landscapes of Injustice Project.” After Pearl Harbor, the Ogaki family would be scattered to Japan and Ontario. Interestingly, throughout the period from 1942 to 1948 they found support from “compassionate individuals who believed in the Japanese Canadians’ right to call Toronto home.” They rebuilt in Toronto “with like-minded individuals who believed in fostering inclusivity,” but never resettled in BC.

With “Working Title,” Matt Rader introduces the last three journeys which bring us back to the present iteration of Cumberland and raises important questions about Cumberland’s current trajectory. Rader uses the “movie script” technique to present a kaleidoscopic series of stills reflecting on his experience, flashing back to the beginning of this century when “run-of-the-river projects” associated with First Nations were all the rage and were being sold to the public by the Campbell government as “environmentally friendly,” to a movie project focused on Goodwin. It reviews the complexity of Cumberland’s history and its association with resource industries exploiting First Nations territories that trigger pollution and a subsequent environmental consciousness. Fundamentally, Cumberland becomes a “black box we can fill with content for potential investors” scripted by “two-pale-skinned men sitting in Tenison’s house doing our own men’s group for the purpose of making money.”

It’s this same ambiguity that is brought forth again in Andrew Findlay’s “Tales from the Trail” which presents a good account of the anarchist building of North America’s fifth most-used trail-bicycling network, and the birth of UROC (United Riders of Cumberland). A product of the Dunsmuir land grant, Cumberland is surrounded by private land owned by a variety of logging companies. Over the past couple of decades UROC together with the Cumberland Forest Society has been able to buy back large forestry blocks surrounding the village, and has been able to negotiate agreements with MOSAIC to have access to build trails through forestry lands. This has turned Cumberland into a Mecca for trail-bike enthusiasts. This is not without mixed up and down sides. It has brought successful “green capitalism” from the bike, beer, and yogurt industries, and grown local champions in trail riding. That’s “success” if you believe in the fairy tale that capitalism can actually be ‘green.’

Ironically, Cumberland today, after all is said and done, remains more capitalist than ever. Somewhat metaphorically, the main avenue aptly remains “Dunsmuir Avenue,” and is nowhere near being renamed “Naylor Avenue,” as it should if social justice were more than a byword. In a starker reality, with the closing journey, “Welcome Poles,” Grant Schilling reminds readers that Cumberland’s main industry remains a soaring real estate market and taxes that put basic housing out of reach of many young people and have caused older ones, who created what Cumberland is today, to move out. Green capitalist investment in Cumberland has led to the gentrification of Cumberland over the past decade. The trail bike Mecca is also a developer’s proverbial little house in Nevada. Stunningly and dismayingly, for a village that revels in the memory of Ginger Goodwin and its progressive values, Cumberland has never developed a co-housing project. It now struggles with social housing, and has instead enabled the sprawl of energy inefficient big-pipe developments of big “little boxes” that are locally unaffectionately known as “Little Alberta.”

Grant Schilling closes the volume with a defining question for this excellent book, that should inspire British Columbians to collectively reflect on the social and environmental challenges we all face today. He provides two reality checks on that question to reflect on. Did Cumberland, as one councillor purports, “do things right” and is now “a victim of its success?” If the objective was consistent with the Naylor/Goodwin heritage, the outcome is not a success. As Bob Dylan said: “There is no success like failure, and failure’s no success at all.” Success by what measure: unsustainable growth of a social cancer that talks of inclusivity, but that in practical terms excludes and marginalizes the average young person and pushes older residents out? That’s a confirmation of actual failure, not success.

As with corporate market-based approaches to climate change pushed by all levels of government, Cumberland Village council was mesmerized by a top-down economic model that guided poor urban planning. They increased real estate sales and grew property taxes to pay for gentrification, but in doing so they have endangered the spirit and ferment of socio-economic change and social justice, which remains essential to what makes Cumberland different. Schilling is right: “the forces that displaced Indigenous people – the endless wheel of capitalism, colonialism and an emphasis on growth – have us all in a hammerlock. It’s hard to be economically inclusive in a capitalist society. We still need what Joe Naylor and Ginger Goodwin fought for.”

As long as that is said publicly, and it stimulates an open conversation within the community, as this book should, there is still hope for social justice in Cumberland. There is hope yet for Naylor’s generous vision in the choices that new generations will have to make. Rhonda Bailey is to be congratulated for her excellent editorial work on this volume for the Cumberland Museum and Archives.

*

Regular contributor Dr. Loÿs Maingon would like to point out, from his home on the Tsolum River near Merville, that he pays taxes in Cumberland and revels in his grandchildren’s future there, particularly that of Atla. He is an avid naturalist and a registered professional biologist, past president of the Comox Valley Naturalists, and webinar host for the Canadian Society of Environmental Biologists. Arrested at Clayoquot Sound in 1993, Loys remains a strong advocate for social, economic, and environmental change. He contributed a chapter to Clayoquot & Dissent (Ronsdale Press: 1994), and authored Field Guide to Basic Lichens of Strathcona Park (Strathcona Wilderness Institute Press: 2022). [Editor’s note: Dr. Loÿs Maingon has reviewed books by M.V. Ramana, Arthur S. Reber, Frantisek Baluska and William B. Miller Jr., Peter R. Grant, Joel Bakan, Melissa Aronczyk & Maria I. Espinoza, William K. Carroll (ed.), Philippe D. Tortell (editor) for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

- Charles Fletcher et al. (2024). Earth at Risk: An Urgent Call to end the age of destruction and forge a just and sustainable future. PNAS Nexus: 3: 1-20. ↩︎

- Ross Barkan (2024) “Gen Z’s politics are hard to categorize – and a harbinger of a new political order”. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/dec/23/gen-z-millennial-politics-new-order ↩︎