A tragedy of generational trauma

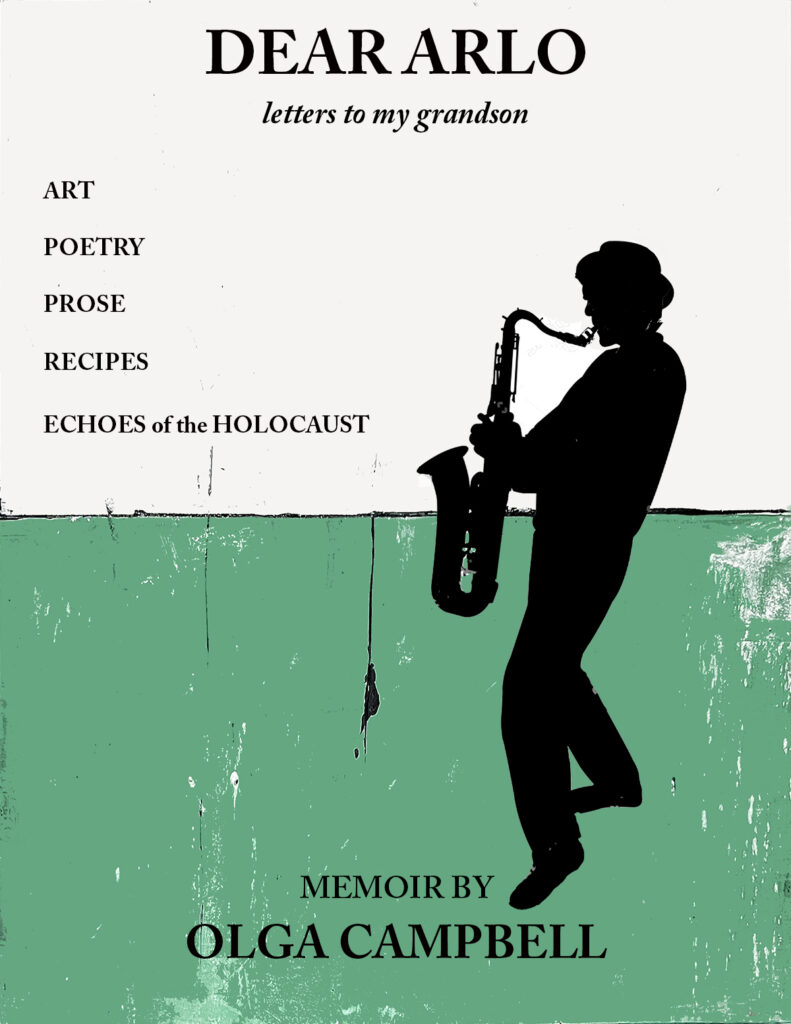

Dear Arlo: letters to my grandson

by Olga Campbell

Vancouver: Jubaji Press, 2024

$21 / 9789981291130

Reviewed by Valerie Green

*

This memoir by Olga Campbell is a mixture of prose, art, poetry, and recipes interspersed with letters to the author’s grandson, Arlo. It tells the tragic story of a legacy of trauma.

Campbell herself is a second-generation holocaust survivor born to a woman who lost her entire family in the holocaust in Poland during the Second World War but survived the horror herself. Her mother’s pain of survival and all that she had witnessed had a profound effect on her and lived on through her daughter into another generation.

However, the intimate story that Campbell shares with her readers is in essence a healing tool for families who have also experienced generational trauma. It is the story of her survival expressed through her art, her poetry, and especially through the letters she writes to her grandson telling him stories of where his ancestors came from while hoping for a brighter future for him.

I found the book very moving from the very first letter to Arlo to the last page. The images of her own art and of others are breathtaking.

Her first letter to her grandson begins:

I am writing this book as a legacy for you. A multidimensional memoir. A compilation of my writing, my art and a few family recipes. These writings and art are my responses to events in my life. Losses, trauma, grief . . . and the joy, happiness and love ….

I will begin by telling you my parents’ story, your great grandparents’ story,

Love, Babi

That story is heartbreaking. Campbell’s parents, Tania and Klimek Dekler, were a young couple living a happy life in Warsaw before the war. Then in 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland from the west, and the Soviets from the east, life was never the same again.

The author’s artwork, poetry, and recipes are peppered throughout her memoir Dear Arlo

Although antisemitism existed in Poland already, Tania and her twin sister, Mania, had never experienced it themselves but in 1939 it became rampant, so Mania decided to move. It seemed to be safer to live under Soviet rule in the east rather than under the Nazi regime. She wanted Tania and Klimek to join her which they did in 1940 and settled in Eastern Poland (Bialystok). The family had always been secular and had previously had both Jewish and non-Jewish friends.

The author’s father, Klimek, however, soon wanted to return to Warsaw where he had been a successful lawyer, but when they journeyed home, Klimek was arrested at the border and sent to a concentration camp. Only Tania, who was pregnant at the time, was allowed to return to Warsaw. When Tania went back to the border later to search for her husband she too was arrested and put in a concentration camp.

Her experiences and those of her husband Klimek were devastating to say the least. Many of those experiences stayed with her for the rest of her life. The author describes how her parents spent two years in concentration camps forced to do hard labour, during which time the author’s mother lost her baby due to poor nutrition when the baby was only four days old. Eventually her parents found one another again through the Red Cross and were sent to Bagdad, Iraq, where the author was born in 1943.

Sadly, Tania Dekler never found out what had happened to her sister, Mania, her parents or any members of her family. Despite searching records, she did not find out where or how they might have died. Having a strong connection to her sister, she felt sure she knew she had died.

The trauma of losing so much of her life stayed with her even after the war when she and her husband emigrated to Canada and lived in Vancouver. There they worked hard raising their daughter. But Tania never talked to her daughter (Olga) about those heart-wrenching memories probably “because it was too intense for her. My mother was active and involved. She worked (as a practical nurse), she participated in life, she laughed, and she danced, but at night in her room, she cried.”

Tania died from cancer at the young age of 52 leaving all the trauma and sadness behind in the heart of her daughter. But although her parents never forgot the past, they had moved on, and had taught their daughter “lessons of resourcefulness, resilience and flexibility. This was their gift to me,” writes Campbell.

Olga Campbell’s own life was also marked with loss and deep sorrow. Having to experience the loss of both her parents, she also lost her own beloved husband, Chris, who died of a stroke at the young age of 49. She describes this loss through some beautiful poetry in words such as:

“. . . the silence resonates throughout the echoes of the solitude that fills me . . . where is the joy and laughter? The myth remains.”

Or – “the empty silence of the world around me seems to fill my tomorrows.”

Campbell tries valiantly to not think about all the happy times with Chris when she writes: “I am not thinking about all this because it hurts too much.”

And yet she has managed to get through all the pain and loss and that of her parents by expressing hope to her grandson Arlo as she writes of all these life experiences, both her own and those of her parents. It is important to her to let her grandson know where he came from because her memoir is a legacy of hope both for him and for all those who have suffered through loss and generational trauma. This is a beautiful story of renewed hope.

*

Valerie Green was born and educated in England, where she studied journalism and law. Her passion was always writing from the moment she first held a pen. After working at the world-famous Foyles Books in London (followed by a brief stint with MI5 and legal firms), she moved to Canada in 1968 and embarked on a long career as a freelance writer, columnist, and author of over twenty nonfiction historical and true-crime books. Hancock House recently released Tomorrow, the final volume of The McBride Chronicles (after Providence, Destiny, and Legacy). Now semi-retired (although writers never really retire!) she enjoys taking short road trips around BC with her husband, watching their two beloved grandsons grow up and, of course, writing. [Editor’s note: Valerie Green has recently reviewed books by Beka Shane Denter, Kate MacIntosh, Rosemary Neering, Winona Kent, Michael L. Hadley, Jason A.N. Taylor for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “A tragedy of generational trauma”