If you can keep it

On Canadian Democracy

by Jonathan Manthorpe

Toronto: Cormorant Press, 2024

$19.95 / 9781770867543

Reviewed by Matthew Downey

*

Canadian politics are a mess, and it is obvious in the words of our parliamentarians. The fact that the Loyal Opposition party is running with the slogan ‘Canada is broken’ speaks to the appeal of this assessment. It is also indicated by the Prime Minister’s recent appearance in New York on the U.S talk show Late Night with Stephen Colbert, in which he described how Canadians are struggling to an audience that ostensibly believe Canada to be a mythic land of unicorns. There is an irony to the way that politicians seek to utilise rhetoric indicating major issues with our political system. Like Peter Finch’s character in Network exhorting his primetime television viewers to get ‘mad as hell’ at the system in order to get better ratings, Members of Parliament namedrop crisis for political purchase without giving any indication of the true cause. In On Canadian Democracy, Jonathan Manthorpe, one of the country’s most prominent journalists, uses his decades of experience as a hands-on observer to elucidate what is truly going wrong.

The enduring image provided by Manthorpe – one that bookends On Canadian Democracy – is the comparison of the state of Canada to that of the official home of its Prime Minister. The reader is brought to ponder the neglected crumbling façade of 24 Sussex, overgrown by weeds, infused with mould, and seemingly abandoned by its caretakers. There are significant blockages in the political will to go about the repair of the Prime Minister’s residence – likewise with his country. To Manthorpe, the crux of the problem is that Canadians do not feel represented by their elected government; they have neither trust nor interest in Canadian institutions. Of particular concern is the state of Parliament. It is easy enough to observe the degradation of this institution by simply viewing the histrionics mislabelled as debate displayed in the House of Commons. Manthorpe’s strength is in drawing connections between general degradations in the grand scheme of Canadian constitutional politics to what many see as simple misbehaviour exhibited by grandstanding politicians. Many may be surprised to hear about such fundamental problems with Canadian democracy – the country is consistently ranked high by groups charting the health of democracy worldwide. However, as Manthorpe states, such rankings are based on elections, not what they produce. A nice façade may obscure walls riddled with asbestos.

Canadians have long derided the American tendency toward celebrity politics; both the entry of Hollywood actors into elected office and the treatment of lifelong politicians as glamorous stars in their own right are seen as examples of unserious politics. As Manthorpe characterises it, Canada has its own problem with celebrity in politics. Of major concern is the Canada’s particular methods of electing our political party leaders. Whereas in other Westminster parliamentary systems, such as the UK and Australia, the elected MPs belonging to a party – called the Caucus here – have a central role in appointing their leader, in Canada this is not the case. Here, party leaders get a ‘popular mandate’ from party members, an incredibly small percentage of the overall population, which might nonetheless be held over the heads of Caucus. To Manthorpe, Canadian politics has been turned into a sport in which teams are constantly preoccupied with gaining points and winning the electioneering game. While it only natural that politicians want to win as many elections as they can, when the only measure of success is the number of years a government has in power it is clear that any motivation for honourable conduct in parliament is rapidly degrading.

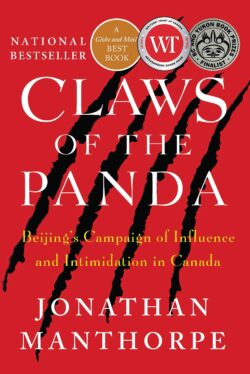

(Cormorant Books, 2020). As reviewer Matthew Downey writes: “To Manthorpe, Canadian politics has been turned into a sport in which teams are constantly preoccupied with gaining points and winning the electioneering game.”

Of all of Canada’s idiosyncratic troubles, perhaps the most encompassing crisis is the powers of the leaders of its political parties. Party leaders have a degree of dictatorial prerogative in Canada that is unheard of in other countries. In British Columbia, we witnessed this manifested in a strange way when BC United leader Kevin Falcon was able to effectively dissolve his party without consulting his caucus. Manthorpe endorses the idea that the leader should be accountable to the caucus, who are elected representatives, rather than the party membership, which represents an incredibly small percentage of the population. Indeed, a seemingly popular mandate directly awarded to the party leader, as can be observed in current political circumstances, increases the degree to which MPs are beholden to an agreeable personality cult. We may roll our eyes at the successive slew of Prime Ministers the UK has seen since Brexit, but ultimately it represents a degree of party accountability that can only be hoped for here. Scandals today are shrugged off where once they would trigger a resignation. This is rooted in the hubristic assumption that the leaders have been given a ‘popular mandate’ to wield over their colleagues.

Throughout On Canadian Democracy is a healthy amount of wariness of measures that on the surface seem to be progressive steps toward democratisation. Manthorpe takes great issue with our mode of appointing Governors General, being that the Viceregal head of state is essentially a patronage appointment of the Prime Minister. Likewise, the disfunction of the Senate is of importance as well. However, Manthorpe is quite discouraging of an elected Governor General, or an elected Upper House. Similarly, Manthorpe exhibits a scepticism towards reforming the First Past the Post electoral system to Proportional Representation. This might leave some more reform-minded readers taken aback – one might tend to assume the supreme virtues of democratic consultation as the fairer method of appointing our political leaders. This assumption of the benefits of a democratically elected head of state, and of the more direct methods of electing members of parliament associated with proportional representation, are countered by Manthorpe’s cautious warning of creeping dangers and unintended consequences. On Canadian Democracy recommends reform, but concurrently warns of idealistic calls for change. The prevalence of radical parties’ presence in governments elected under Proportional Representation are duly noted, as is the negative potentials of politicising the head of state.

The most powerful achievement of Manthorpe in this book is in standing firm against the teleological narrative, endorsed by many political actors including the Prime Minister, surrounding the patriation of Canada’s constitution and the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The government lauds ‘Charter values’, and according to a 2023 Angus Reid poll Canadians have been increasingly viewing the use of the Notwithstanding Clause, allowing Provincial legislatures to democratically opt out of certain Charter measures for 5-year periods, to be problematic. However, polls also indicate that only a small number of Canadians really know what is included in the Charter, with many confusing its text with that of the U.S Declaration of Independence. It would seem that many Canadians have chosen to move past the problems inherent in the adoption of the Charter, but Manthorpe is admirably hell-bent on preventing such a fall into comfortable constitutional ignorance. For Manthorpe, what the Charter did to parliamentary integrity and Provincial relations was undermining to Canada’s entire political order. As Manthorpe puts it, the Charter, attempting to illuminate in bold lettering the rights of Canadian citizens under the assumption that new Canadians less versed in parliamentary systems would not otherwise understand their constitutional protections, transferred control over social policy from the people’s representatives in parliament to an unaccountable appointed collection of judges. Likewise, Manthorpe states Pierre Trudeau’s goal in the patriation process to have been scoring and end goal on the provinces, essentially using the constitution as a weapon in the gladiatorial combat of the politics of federalism. Indicative of this is the fact that Quebec never signed on to the Constitution Act, 1982, and both attempts to bring them into the fold, first at Meech Lake and then at Charlottetown, were shut down with the public support of Trudeau the Elder. These issues have been obscured with time, but they are still lurking below every mention of ‘charter rights’ in the House of Commons and every squabble between Premier and Prime Minister. Manthorpe’s support of increased use of the Notwithstanding Clause stems from his belief that only a full-blown constitutional crisis will allow for the return of parliamentary supremacy and the ability for Canadians to truly know and identify with their democratic order.

Manthorpe’s analysis of the state of Canadian democracy is indeed extensive, but it does miss out on a more detailed discussion on two major topics. Though relating the substantial problems at hand regarding the Governor General and how the viceregal office is appointed, there is very little mention of the role of the monarch. Manthorpe is far from recommending republicanism in Canada, but he does however contribute to the decrease in visibility of the Canadian Crown, which is at the centre of our constitution regardless of one’s personal identification with the institution. The King might be effectively symbolic in the constitutional order, but symbols can be quite important in encouraging the honourable behaviour of political actors. The second topic that could have used more attention is Indigenous issues. The Royal Proclamation of 1763, which necessitates the respect of treaty relations between the Canadian governments and First Nations, is a foundational constitutional document. The relationship between the Crown and Canada’s Indigenous peoples deserves to be mentioned in a discussion of how to establish a proper democratic system and encourage widespread identification with our civic institutions.

Overall, On Canadian Democracy is greatly successful at highlighting a wide array of issues to be found in Canadian politics today. Manthorpe covers a large amount of territory – too much for me to summarise succinctly here – and yet with journalistic tact manages to provide direct and digestible analysis. Whether one is a political buff already or is simply questioning why to care about politics at all, books such as this serve a noble purpose in buoying democratic awareness through the raising of questions and the continuing of conversations. Canada might not be broken, but it is certainly neglected. While we have been focusing on the housefire across the street, we’ve been suffering water damage in our basement. Poor metaphors aside, Canadians need to get interested in their own system of government. Manthorpe’s book would be a good way to start. To misquote the estimable (though traitorous) Benjamin Franklin: in Canada we have a parliamentary democracy, if you can keep it.

*

Matthew Vernon Downey is an independent writer and researcher based out of Victoria, B.C.. He has degrees from UVic (BA hons) and the London School of Economics (MSc) [Editor’s note: Matthew Downey has also reviewed books by Robert Amos, Alan R. Warren, Gregor Craigie, Robert Crossland, Donna (Yoshitake) Wuest with Joe W. Gardner, and Mike Whalen for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster