‘Ache towards rectification and inclusivity’

We Oughta Know: How Celine, Shania, Alanis and Sarah Ruled the ’90s and Changed Canadian Music

by Andrea Warner

Toronto: ECW Press, 2024

$24.95 / 9781770417748

Reviewed by Catherine Owen

*

It’s my birthday. I’m reading Andrea Warner’s We Oughta Know: How Celine, Shania, Alanis and Sarah Ruled the ’90s and Changed Canadian Music and thinking about time and era and how they shape identity (and I’m just now pondering a titular predilection for calling women by their first name and men by their last or full name). Warner, slightly younger than I, indubitably had more Canadian women playing music to look up to during her teen years. I, an overall metalhead, thought I was a feminist for being the only girl who listened to WASP in my Grade Nine class. Guided, in part, by a father who gave me positive attention mostly for not displaying feminine traits, I imagined that the best kind of woman I could become was a male-tinged one, a being both capable of masculine-cool intellectual discourse and a certain raw strength that seemed dude-like. Even in the ‘90s I recall the closest I came to liking “chick music” was Ani DiFranco. It was all very confusing. And, as Warner elucidates, sometimes rather wordily, it was for her too. And it still is for young girls today. Who should they mimic? Rock out to? Honour? Should female performers be lauded for showing skin or reviled? Can one be a romantic and still be fiercely independent? Should we pay attention to any “shoulds” at all?

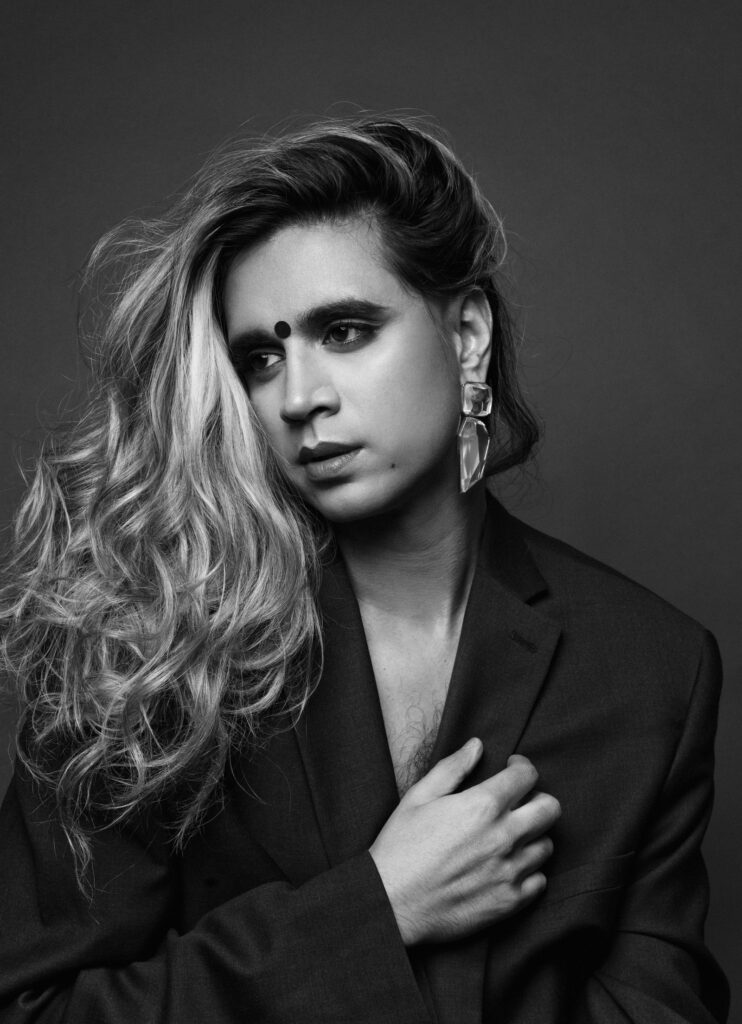

The book (a re-release and partial updating from its initial 2015 publication, including the addition of a Vivek Shraya preface to widen the definition of womanhood even further) focuses on four female musicians who came to serious prominence in the ‘90s: Celine Dion, Shania Twain, Alanis Morissette, and Sarah McLachlan. Warner presents this quartet has having been firmly binarized in her mind when she was an adolescent, with Dion and Twain rejected for their respective sappiness and sluttiness (at least wardrobe-based), and Morissette and McLachlan wholly embraced for their anger and inclusivity of a deeper, darker, female experience. Of course, this text is meant to rectify Warner’s (and by extension other young women’s) early black and white blanket judgements, to turn Dion and Twain into more empowered visions and to shade Morissette and McLachlan with certain reconsiderations regarding their complexity and community.

We Oughta Know (the title derived from a Morissette tune) begins with a personal introduction by Warner that overviews her position within ’90s culture and attitudes towards female performers, her main concern being to confront her own “complicity” within a misogynistic society in which women can be one thing but not another, and if they show their bellybuttons then, hey, they are instantly to be disregarded for their intellectual or artistic talents. Concluding this part with the direct statement: “Actually, fuck it. We’re beyond apologies. It’s time to atone,” Warner then offers up four chapters, each dealing with the individual artists in question and focusing not only on aspects of their lives and careers, but on how the songs on their top-charting albums elucidate attitudes about love, sexuality, rage, empowerment, and other key issues.

Along the way, and especially regarding Dion and Twain, she’s exceedingly honest about both her appraisals of the music (“There’s passion in Dion’s songs, but it’s a sexless passion, like a Ken doll’s beige genital wasteland” oooooo!) and her cutting assessments of herself at an age when she was “secretly conservative” and had the tendency to minimize the achievements of a singer like Twain due to her “damned bare midriffs.” In her aim to acknowledge her nascent judginess, she can go a bit over the top, and also make seemingly contradictory statements like “Shania Twain is, at long last, queen of herself,” (when who is anyone to define that exalted state), but her energy is captivating. The segments on Morissette and McLachlan are tame by comparison, but this is because she was (and is) a fan and it’s much harder for her to critique her consistent heroines than to strike a balance with her former nemeses. Her deeper intent in these chapters is to position these latter two artists within their contributions to the bigger picture of women in music, and particularly through the three-year run of Lilith Fair, instantiated by McLachlan. Here’s where Warner’s critique is honed, via Alanis and her successes being deemed a “huge part in opening that door” to the creation of such “all-women music festival(s),” even though she can see now that these visions of achievement were still narrow, as these were only wins for “white, straight, cis women” as a “general sexism and misogyny persisted.”

In the subsequent chapter (which might have been placed first as an era’s overview?), Warner imagines a new kind of Lilith Fair that’s as racially, sexually, and et cetera, much more inclusive, listing a wide range of artists and genres that could be on a more essential bill (I was wondering where Toronto all-female powerhouse group The Beaches was in this re-issue!). She also touches on how grief, sexual incursions and other growing senses of injustice can connect one to music in a truly vital way. For Warner, her sense of herself as a feminist and her love of music (and even other aspects of culture like The Baby Sitters’ Club books and Miss Piggy, the Muppet) were intertwined. Probably my favorite chapter is “Adventures in Sexism: Media, Music and Mucking up the Boys’ Club,” which begins, “It’s hard to pinpoint the first time I realized I mattered less to somebody because I was a girl.” She then carries on beyond her own personal experience to pastiche media critiques of her main four female musicians, demonstrating the cruel extent to which they had to combat multiple forms of reductionism, from being compared to other women performers, to being dismissed as mere puppets of their Svengalis. The final two parts attend more to the Canadian context and the 90s revival, sketching the immense success these musicians had (“Bigger than the Beatles” in terms of charting), underscoring the impact of sexism on artists from O’Connor to Spears, and gesturing towards the need to enlarge the voices of Black, Indigenous, and other liminal-ized artists. The appendix then provides a much more conclusive compendium of crucial female musicians who started their vocations around the ’90s, including Bif Naked, Mecca Normal, and Diana Krall. Andrea Warner’s We Oughta Know, in its 2024 instantiation, is perhaps overloaded with its ache towards rectification and inclusivity, but overall it does what it set out to do, celebrate these four powerhouse creators with a deeper sense of the larger context, both of Warner’s individual self, and of our Canadian society as it was then, as it is now, and within the potential it can have for a fiercer embrace of a more just future.

*

Catherine Owen was born and raised in Vancouver by an ex-nun and a truck driver. The oldest of five children, she began writing at three and published at eleven—a short story in a Catholic school’s writing contest chapbook. Since then, she’s released fifteen collections of poetry and prose, including essays, memoirs, short fiction, and children’s books; her latest are Moving to Delilah (Freehand Books, 2024) and The Weather Says (Carbonation Press, 2024). She also runs Marrow Reviews, the podcast Ms Lyric’s Poetry Outlaws, the YouTube channel The Reading Queen, and the performance series, 94th Street Trobairitz. She currently teaches at Concordia University and NAIT. [Editor’s note: Catherine Owen has also reviewed books by Minelle Mahtani, Eve Joseph, Julie Paul, Sharon McCartney, Andrea Scott, and Tom Wayman for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “‘Ache towards rectification and inclusivity’”

Thought-provoking review of Warner’s work. What do you think sets his storytelling apart from other contemporary writers?