‘Mutual respect among neighbours’

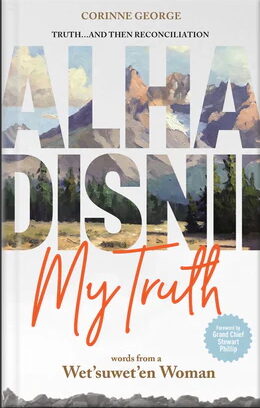

ALHA DISNII – My Truth: Words from a Wet’suwet’en Woman

by Corinne George

Calgary: Medicine Wheel Publishing, 2024

$19.99 / 9781778540417

Reviewed by Sage Birchwater

*

“Truth…and then Reconciliation!” That’s the order things must go Corinne George says in her memoir ALHA DISNII – My Truth: Words from a Wet’suwet’en Woman. Reconciliation between Canada and Indigenous people must begin with truth. After that we can reconcile, she says. ALHA DISNII nails down the truth part.

George starts off by sharing her family genealogy and her connection to the land in the Bulkley, Nechako, and Skeena river watersheds. She explains how the Wet’suwet’en and Gitksan oral history traditions and balhats (potlatch) system defines territorial ownership and mutual respect among neighbours.

This was a system fully in place before European colonizers arrived to change the way things were done on the landscape more than 200 years ago.

While fully Indigenous, George grew up non-status in the predominantly white settlements of Telkwa and Smithers. She explains how her father and his family lost their status by living off-reserve on preempted land, and how her mother lost her status when she married her dad. After that she wasn’t allowed back on the reserve to see her own family.

George benefited from being classified non-status because it shielded her from enforced confinement in Lejac Indian Residential School in Fraser Lake like her mother endured. So she avoided the overt degradation and humiliation that residential school heaped on Indigenous kids. Things like being shamed for their culture and being punished for speaking their Wet’suwet’en or Dakleh languages. Perhaps most important, she wasn’t locked away for ten months of the year in an institution separated from her family and culture.

Instead George got to spend time growing up with her parents and grandparents immersed in the Wet’suwet’en way of life. She got to watch her grandmother work with leather and prepare traditional foods for their meals, and take part in the oral history and balhats traditions. “My Grandma made moccasins and buckskin coats to navigate both the Wet’suwet’en and Western economies,” she says.

But growing up off-reserve, she was one of few Aboriginal students in the predominately white preschool, elementary, and high school environments. So it was sometimes hard for her to fit in and be accepted, and she felt invisible to some of her peers. Yet she acknowledges the kindness and generosity shown to her by kids who treated her as an equal and accepted her as a friend.

And with a foot in both worlds she sometimes dealt with poverty that arose from her family being outside the mainstream economy.

George introduces us to terms we’ve heard lots about recently, but may not be something we fully understand. Cultural genocide, systemic violence, lateral violence, generational trauma, and that persnickety term, reconciliation.

She speaks of the Balhats system and the oral history protocols Wet’suwet’en society is founded on. This constrained some of her truth-telling because the oral history stories are intended to be spoken not written. “Once something is written down it changes the integrity and nature of the oral tradition,” she explains.

She says her parents and grandparents guided her to keep one foot in her cultural traditions while striving for success in the Western world. “So we strived for the best of both worlds.”

One thing that makes George’s story interesting is her relationship to the Catholic Church. When she entered elementary school her parents decided to send her to Saint Joseph’s Catholic School in Smithers, about 15 km down the road from her home in Telkwa. This was a day program where she traveled back and forth to school every day. And unlike the public school in Telkwa which had very few Indigenous kids, the Catholic school had an equal number of Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

Very quickly she got to experience the systemic violence the Catholic school tradition is noted for. After watching an injured student get taken into the school, she got a severe strapping for peering in the window to see if he was okay.

Despite this extreme punishment, George remains positive in her outlook toward the Catholic Church. While acknowledging the pain and trauma suffered by many Indigenous children across the country at the hands of the priests and nuns, she says her relationship with the Church was fostered by her friendship with Bishop Fergus O’Grady who gave her the Sacrament of Confirmation when she was nine years old. She and the Bishop continued to stay in touch many years afterwards. “Bishop O’Grady was kind, compassionate and caring,” says George, “And he always acknowledged and respected me.”

Many years later on her healing journey, George felt compelled to reconnect with her spirituality and faith. Particularly poignant was her memory of singing Carrier hymns as a child.

After graduating from high school in Smithers in 1989, George set off for Vancouver to pursue post secondary education. She admits as a naïve 18-year-old from a small town she made bad choices and got caught up in the darker side of the party scene. Then she got involved with a man 14 years her senior who started to abuse her. Her life quickly spiralled out of control with alcohol fueling the toxic violent relationship she was caught up in, and it took her five years to break free from it.

George describes how she hit rock bottom, and credits the kindness of certain people who helped her get back on her feet. But it was her own inner strength that ultimately pulled her through.

Reconnecting with her Wet’suwet’en culture was key to her recovery. “I knew it was critical for my physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual survival to reconnect with my ancestral ways,” she says. “I started to make drums and to sing as often as I was able.”

She took a job working with youth in Vancouver, and she says that instilled hope.

Five years into her healing journey George’s father passed away, and she flew home to Smithers to be with her mother. When she arrived at her parents’ home, it was full of Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs and members of the community. “I was deeply touched by this expression of love and unity,” she says.

This was the point George felt drawn to reconnect more deeply with her ancestors and culture.”This meant spending time on Niwh Yintah (her traditional territory) and also at the Balhats Hall.”

She also reconnected to the faith-based aspects of the Catholic Church, though she admits she struggled with this in light of the Church’s colonial history of abuse on Indigenous people. She recalled how her ancestors connected strongly with Uttigai (the Creator) through the Church. Particularly dear to her was her memory of singing Carrier hymns.

Back in Vancouver George started to regain her physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual health.

A year after her father’s death, she met John, a former Catholic priest, and they formed a close friendship. Soon their friendship blossomed and they got married.

George went back to post secondary school at the University of Lethbridge with the goal to becoming a high school history teacher. With every history course she made the point of viewing the narrative through an Aboriginal lens.

Recognizing the need to connect more fully with her physical and spiritual well-being she took up the martial art of Aikido. This is something she and John did together, and he encouraged her to stay with it when she felt like quitting.

After acing her Bachelor of Arts degree, George continued her studies by enrolling in a Master of Arts degree in history at the University of Calgary. She credits her mother for encouraging her when she had doubts, by telling a story of her grandfather overcoming his fears packing horses through narrow precipitous canyons during construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. “We must not give up,” she advised her.

Once again George aced her academic studies and earned her Masters degree. Then she started pursuing a PhD on British Columbia history at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. Her focus was on the Wet’suwet’en oral histories as they pertain to the Indian Act and the Wet’suwet’en hereditary system.

Once again, she aced her coursework and began studying hard for her comprehensive exams. “I put in 15-hour days and read 150 books,” she says.

She felt on top of the world and ready to write her exams, but she was also aware that if she didn’t pass, that would be the end of her academic journey.

It’s hard for the reader to understand exactly what happened. George got an email advising her to call her supervisor. In their conversation she was told she didn’t pass.

“Our conversation felt harried and my supervisor didn’t seem interested in giving me any more time than was necessary,” George says. “My heart shattered. At that point my dream of completing my PhD in history was completely gone.”

She says her supervisor’s level of support was minimal at best, and George felt her Wet’suwet’en world view was not honoured. “The subjective results of my comprehensive exams were based on Western understandings.”

Discouraged, George felt she needed to go back to work. She got a job with the Union of BC Indian Chiefs as a researcher in Vancouver and stayed physically active regularly climbing the Grouse Grind and continuing her practice of Aikido.

In 2015, she and her husband moved back home to Wet’suwet’en territory to spend time with her aging mother. In the process she reconnected with the trails of her ancestors and became more fully immersed in the Balhats traditions.

She started working for the College of New Caledonia as the regional principal in Burns Lake teaching Wet’suwet’en culture and history. Gradually the reconciliation process became more evident to her. She says her roles at CNC shifted and changed with time. “But regardless of my roles, my vision and focus remained the same: to highlight the voices of Aboriginal people and do whatever I can to enhance relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the community.”

ALHA DISNII – My Truth is well written and well edited. A lot gets said in just a few words.

I look forward to a future volume by this author. I’m anticipating a book where Corinne George will tell us the story of how she achieved her PhD. That’s the one thing missing from this narrative.

*

Sage Birchwater, a long-time resident of the Cariboo-Chilcotin, has written several books about the area including Chiwid (New Star, 1995). Born in Victoria in 1948, Birchwater was involved with Cool Aid in Victoria, travelled throughout North America, and worked as a trapper, photographer, environmental educator, and oral history researcher. Sage served as the Chilcotin rural correspondent for two local papers for 24 years while raising his family south of Tatla Lake. He has also lived in Tatlayoko, where he was a freelance writer and editor, and Williams Lake, where he was a staff writer for the Williams Lake Tribune until his retirement in 2009. His other books include Williams Lake: Gateway to the Cariboo Chilcotin (2004, with Stan Navratil); Gumption & Grit: Extraordinary Women of the Cariboo Chilcotin, (2009); Double or Nothing: The Flying Fur Buyer of Anahim Lake (2010); The Legendary Betty Frank (2011); Flyover: British Columbia’s Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2012, with Chris Harris); Corky Williams: Cowboy Poet of the Cariboo Chilcotin (2013); Chilcotin Chronicles (2017), reviewed here by Lorraine Weir; and Talking to the Story Keepers: Stories from the Chilcotin Plateau (Caitlin Press, 2022), reviewed here by Richard T. Wright. Editor’s note: Sage Birchwater has recently reviewed books by Sandra Hayes-Gardiner, Lorraine Weir, with Chief Roger William, Trevor Marc Hughes, Hamilton Mack Laing, Mykhailo Ivanychuk, and Adrian Raeside for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “‘Mutual respect among neighbours’”

Thank you for this engaging review. It raises a number of points I was previously unaware of. I will get the book and read it with interest.

Meanwhile let me offer the following observation on what can sometimes happen at graduate school.

As an undergraduate I did quite well until it came to my honours thesis. The same pattern was true in graduate school. No one ever told me I was ill-prepared to meet the professional standards required.

Looking back now as a sometime law professor, that is a difficult conversation to have with a student, and a difficult message for them to hear—“Why are you only telling me this now?”

It is even harder when the professor is an old, white, male of privilege and the students are young or gender diverse or persons of colour, each having invested so much and with their entire futures on the line.

So professors , however well-meaning, become increasingly risk averse and students then unfairly suffer the consequences when it comes to the crunch.

Thanks for sharing your insight Richard. I appreciate that.