‘Of statistical importance’

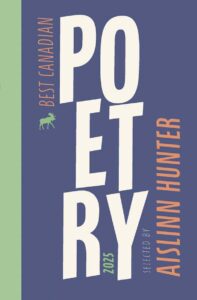

Best Canadian Poetry 2025

selected by Aislinn Hunter

Windsor: Biblioasis, 2024

$23.95 / 9781771966320

Reviewed by Mary Ann Moore

*

The goal of Best Canadian Poetry 2025 is “to offer a series of glimpses that morph into a fairly coherent overview of the current state of poetry in Canada: who is writing, and what, and how?” Anita Lahey, editor of the Best Canadian Series 2025, says as much in the Foreword to the collection.

Among the poets included whose names are well recognized are: Karen Solie, Anne Carson, Erin Moure, and Sue Goyette. Also, Molly Peacock, who inaugurated the Best Canadian Poetry series in 2008 with Tightrope Books. A dozen British Columbia poets also made the “best” list as chosen by Vancouver-based novelist, essayist, and poet Aislinn Hunter, guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2025.

To come up with her selection of fifty poems, Hunter read “a year’s worth of literary magazines” from The Adroit Journal to yolk. She has some wonderful reflections on poetry in her introduction, such as: “In poetry you have your hand on someone else’s heartbeat.”

Hunter (The Certainties) believes that “poems behave like living things.” She found that the “most impactful poems [she] read were sites of feeling–which is to say sites of inquiry, resistance, resilience, regret, provocation, play, grief, desire, glee… the poems [she] dog-eared felt confident and necessary.”

Hunter orders the poems alphabetically by title, and Billy-Ray Belcourt’s poem starts things off. An assistant professor at UBC’s School of Creative Writing, Belcourt is from the Driftpile Cree Nation in northwest Alberta.

His poem also has the volume’s longest title: “According to the CBC, Indigenous Peoples Are Demonstrably More Vulnerable to Illness and Disease, Live 15 Years Less Than Other Canadians.” It begins solemnly—“In my country,/death is a door/that swings open.” It ends with these lines:

Every day they don’t die

isn’t of statistical importance.

And so, every day they wake up

they invent another way to be

unconquerable.

Belcourt says his poetic response to the CBC article released during one of the Covid-19 lockdowns was his attempt “to grieve the loss of the years I won’t be able to live, the years my kin have already lost. I couldn’t help but register my longing for a country that doesn’t generate the conditions in which we died sooner than we should.”

Ancestry and ancestors as well as grief (personal and planetary) are among the subjects that appear frequently in the collection.

In “December’s End” Lorna Crozier writes about her “dead husband.” “I am wintered/with woe,” she says in her writing of the garden that Patrick Lane left behind.

Kayla Czaga offers surprise and unexpected turns in her poem “Safe Despair,” inspired by her rereading of Emily Dickinson’s poetry. The poem’s concept sprang from Dickinson’s famous poem “Because I could not stop for Death.” Czaga wondered why the poem’s speaker “might not be able to stop for Death.” Her curiosity led her to some light and quirky humour—

Because she could not stop for Death,

Death drove alongside, shouting —

Emily, get in the car.

. . . .

Death said dead girls didn’t understand him.

Only Emily could understand him.

Only Emily and her meters of lace,

museum of ceramic feelings, her breath

flogging the pane and long trembling

fingers could understand him.

Yes, the poem says “flogging”!

While Death drives a car and even gets a job in Czaga’s poem, Robert Bringhurst writes of language in “Life Poem.” It begins with an epigraph: “in memoriam Stan Dragland, 1942-2022.” Not that Dragland, “one of the best friends Canadian literature ever had,” needed a lesson on the nature of language, Bringhurst says. It was that language and “the perils of bad ecological behaviour” happened to be among the topics Bringhurst is always thinking about, including at the time Dragland died. He writes, “Life has been married to language so long that you/might think the two could finish or begin each other’s/somersaults and sentences. They don’t. It only seems/as if they do.”

Bringhurst’s beguiling poem about language, what it is and what it is not, as well as a state in which there is no language at all, provokes as well as amuses—

Life heard us coming and will be here watching closely,

hungry, wary, wounded, wordless, like the snakes

of Fukushima and the lynxes of Chernobyl,

when we go–but will not speak of us or curse us

or have any name to give when we’re gone.

In the midst of despair, Evelyn Lau writes of “an attempt to call attention to the startling moments of beauty that exist in the rain and the dark” she says of “Mindful (for Kurt Aydin).” On a city street “when a streetlight shone on the rain-slick hedge,” the speaker remembers to breathe, to let herself off the hook—

Let’s say tonight, this is enough–

bronze glow in the west, fog slouching south,

bridge visible again. We’ll sip priceless tea

from some forgotten village, seek notes

of sticky rice, apple pear, snow leopard

Strain it through our teeth like mud-water.

“Poetry is what I start to hear when I concede the world’s ability to manage and to understand itself,” Bringhurst is quoted as saying in the Foreword. “It is the language of the world: something humans overhear if they are willing to pay attention, and something that the world will teach us to speak, if we allow the world to do so.”

*

Mary Ann Moore is a poet, writer, and writing mentor who lives on the unceded lands of the Snuneymuxw First Nation in Nanaimo. This regular contributor to BCR has produced a new chapbook of poems called Mending (house of appleton). Moore leads writing circles and has two writing resources: Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey (International Association for Journal Writing) and Writing Home: A Whole Life Practice (Flying Mermaids Studio). She writes a blog here. [Editor’s note: Mary Ann Moore has also reviewed books by Emma FitzGerald, Susan Alexander & Lorraine Gane, Judy LeBlanc, Kayla Czaga, Christine Lowther, Jude Neale and Nicholas Jennings, and Yvonne Blomer and DC Reid for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “‘Of statistical importance’”