An ‘ever-loud, ever-tempting world’

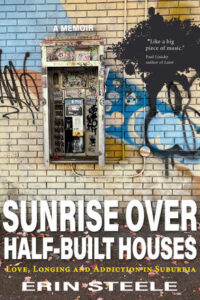

Sunrise Over Half-Built Houses: Love, Longing and Addiction in Suburbia

by Erin Steele

Qualicum Beach: Dagger Editions, 2024

$26.00 / 9781773861500

Reviewed by Carellin Brooks

*

Bestselling addiction memoirs follow certain rules. The protagonist’s struggle must be evident from the very first page, and the stakes must be high from that page—but higher with each subsequent misadventure. The reader races through the book with her heart in her mouth, rooting for our narrator, however unreliable. Will she make it? We want her to—it’s the nature of our human experience and of story. We know she’s still alive because—spoiler alert!—after descending to the depths of despair, she’s here to pen this deceptively workaday description of how far down she went, and how she clawed her way back from the pit. In these types of books the story itself takes over, driving the narrative with a propulsive plot.

Sunrise over Half-Built Houses, subtitled “Love, Longing and Addiction in Suburbia,” takes a different tack. In her debut book, Erin Steele chronicles a typical middle-class suburban upbringing in Surrey’s Fraser Heights. The writer’s parents are no monsters: the worst that can be said of them is that, like billions of us the world over, they would rather not delve into the murky depths of their less pleasant emotions.

Clearly, though, something’s wrong in the life of young Erin. She nicknames her real self Little Me, a mouse so timid it barely ventures into visibility even with her closest intimates. Another girl in school fascinates her, so Erin begins writing the girl creepy anonymous letters. These instruct the girl to be nice to Erin: the anonymous letter writer claims to have done something terrible to her. The police become involved and eventually discover that Erin is sending the letters herself. The remainder of her high school year turns into a predictable hell. As with every time the young protagonist is asked to account for herself, however, the answer to why she did it? “I don’t know.”

That’s true to life: we very often don’t know why we do what we do, and only afterwards—especially in the teen years, when our thinking doesn’t project much into the future—do we realize that we should, perhaps, have foreseen the undesirable consequences of our actions.

When Erin later discovers that she’s a lesbian, it explains her fixation on her classmate. By then, the narrator has already run the predictable gamut of mind-altering high-school experiences: port stolen from her parents’ liquor cabinet, mushrooms, grass, hash, E. Her burgeoning sexuality gives rise to another kind of addiction: Erin recognizes her longing for certain women as essentially unhealthy, less about them as people than her own sense of needing something to fill the existential void within. Music helps, sometimes. So do unhealthier behaviours. During a brief bout of anorexia, Steele notes: “Sometimes the space inside pulls, hard—a black hole. Sometimes it’s rambunctious, like a drunken extrovert at a funeral. Most of the time it just aches. Filling it with food blurs its sharpness; then, paradoxically, so does taking away food completely.”

Where does the void come from, though? Kelowna resident Steele never gives us a definitive answer. There’s no one incident that leads her from the usual teenage pantheon of drink and drugs gradually into the harder stuff. She flunks university and takes a series of dead-end jobs, ending up in a Zellers break room where a co-worker asks her a fateful question: “Are you coming down off crystal?” Why yes, yes, I am. A few pages farther along the two are shacked up together in a run-down apartment and Steele’s new girlfriend is initiating her into the dubious joys of heroin.

The addict’s trajectory Steele sketches here feels familiar from other addiction memoirs: run-ins with the police after squabbles over the few dollars needed to buy the next hit; hours of waiting around for the dealer to show; considerations of what’s left of value that could be converted to cash. At a particularly low point, Steele has been kicked out of her parents’ house, and some acquaintances allow her to stay at their place. Alone in the apartment one day, she hocks the nine-year-old daughter’s DVDs for drug money. Little wonder that she often returns to a temporary bolthole to find her belongings bagged on the porch.

Steele is lucky, if that’s the right word, that her addiction seems to have run its course before the worst of our current fentanyl-riddled opioid crisis. But even in less predictably lethal times, the life of her high school boyfriend and later friend David is a cautionary counter-narrative. At first, David seems more mature and less attuned to the undertow than Steele; one day, when she asks him to buy drugs, he nonchalantly replies that he doesn’t feel like it. But David’s lack of dependence proves an illusion, and soon he’s as hooked as everyone else. David’s parents fund multiple treatment centre visits, including a ruinously expensive last-ditch attempt to get their son clean. Steele is in a restaurant when the call comes from David’s phone, not from him as she expects, but from his mother. The news is not what she expects.

Is this the wake-up call that finally inspires our narrator to get clean? Not really. There’s in fact no one precipitating incident for her turnaround, and that reversal, unlike those depicted in more conventionally structured bestsellers, isn’t particularly quick or decisive. It’s merely that Steele, not notably introspective before this point, looks at her life and ponders which she’d rather be: the addict fixated on the next opportunity to get high, or a person with a lot more to experience?

Even then, she’s unable to fix on the backstory of her addictions:

But what’s it really about? I’ve soothed myself with so many things throughout my lifetime. Does it go back to sucking my thumb? Is there something underneath all that soothing that needs looking at? That needs love? Or is this just a by-product of how we’re all hurtled from the warm provider of the womb into an ever-loud, ever-tempting world where we’re left ever-searching for fulfillment?

In the end, Sunrise Over Half-Built Houses charts the author’s halting steps towards redemption on her own terms. There are no surprises here: feeling your worst feelings, substituting ruinous addictions with healthier ones like the marathon-running she takes up to replace getting high, getting involved with yourself rather than succumbing again to the quick fix of another girlfriend, another drug, another distraction. It’s called growing up, it’s how we all survive, and it’s a far more human, if far less sensational, story than the truncated version in those beguiling if misleading bestselling memoirs.

*

Carellin Brooks is the author of Learned and four other books. Her reading habit, begun in childhood, continues to this day. [Editor’s note: Learned (Book*hug, 2022), a poetry collection about Brooks’ time at Oxford and in the fleshpots of London, was reviewed in BCR by Linda Rogers. Brooks has reviewed Jes Battis, Jen Currin, Daniel Zomparelli, Dina Del Bucchia, Mx. Sly, Debbie Bateman, Michael V. Smith, Buffy Cram and Maryanna Gabriel for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “An ‘ever-loud, ever-tempting world’”