An exercise in futility

The Futility of Aboriginal Law Reform

An Essay by Richard Butler

*

Introduction

Former government lawyer and author Richard Butler writes that there must be a better way than trying to implement the principles of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) through law reform. He sees it an exercise in futility and potentially risky for reconciliation.

Until recently, the main developments in Aboriginal law have been through the courts.

Now, in addition, we have the BC Declaration Act1 and UNDRIPA2 (collectively, the UNDRIP Acts) as quasi-constitutional instruments of Aboriginal law reform.

The UNDRIP Acts provide that our governments must take all measures necessary to ensure the laws of British Columbia and Canada are consistent with the Declaration. In doing so, they must “consider the diversity of the Indigenous peoples in British Columbia, particularly the distinct languages, cultures, customs, practices, rights, legal traditions, institutions, governance structures, relationships to territories and knowledge systems of the Indigenous peoples in British Columbia.”

Some have described the UNDRIP Acts as merely aspirational. If only that were so.

The thesis of this article is that actually using them as formal instruments of Aboriginal law reform in British Columbia is both impracticable and politically improbable. Any such initiative is ultimately bound to fail and, in consequence, would be harmful to the prospects of reconciliation. We need to find a better way.

Braiding Laws

The two UNDRIP Acts would seem to require a comprehensive review of the laws of each level of government, enactment by enactment, to ensure they are consistent with UNDRIP principles. In doing so, they must consider the diversity of Indigenous people who may become subject to those new laws.

Reviewing the relevant Crown laws would itself be a massive task. Add in all the laws of all First Nations across the province, and the task would be multiplied beyond imagining.

But there is a more fundamental problem with the notion of amending individual laws to conform with UNDRIP. That problem lies not so much in how law is designed or operates but in what law is. Here is what I mean:

- The Anglo-Canadian common law tradition involves rights and wrongs. It is focused on individuals. It includes both private rights and wrongs inter se and public rights and wrongs vis à vis the group. In terms of process, the goal is certainty, and the enemy is ambiguity. In terms of results, the outcomes are binary—either guilt or innocence, punishment or vindication, or one or the other party bearing the civil loss.

- At the risk of over-generalizing, Indigenous legal traditions seem to be more about the principle of what’s right and what’s wrong in relation to the natural world and its inhabitants (all my relations). They appear to be about how to conduct oneself in a good way in those relationships, not only at the moment of potential conflict or dispute but also both before and afterwards (seven generations either way). As exemplified in traditional stories, Indigenous laws engage a dynamic process of dispute resolution, embracing ambiguity because it allows for flexibility; and they evidently prefer outcomes that are restorative of both the wrong-doer and the community.

Those differences appear insurmountable in any sort of UNDRIP-generated law-by-law review. Such an approach would be akin to braiding strands of razor wire with streams of water.

Braiding Legal Systems

Perhaps recognizing the problems of attempting a piecemeal approach to the braiding of laws, the B.C. Law Institute (BCLI) has announced a process for braiding legal systems based on the principle of pluralism.

BCLI’s Reconciling Crown Legal Frameworks Program has developed a number of primers to that end. Those primers discuss various legal mechanisms by which pluralism could be advanced.3 In Primer 3, I was surprised to read a quotation taken from an article by Indigenous scholar Gordon Christie which, standing alone, seemed to support the possibilities of pluralism.4

The quotation from Christie’s article sent me scurrying back to his 2019 book, Canadian Law and Indigenous Self-determination.5 As BCLI is exploring pluralism, Christie’s book should give them pause, for a number of reasons.

In the book, Christie’s larger message to Indigenous Peoples is to avoid being pulled into the Canadian legal system if they wish to preserve their self-determination. His article reiterates that same point: engaging a braiding process led by the Canadian state and its courts “is to move directly into a world where the colonial project has been completed.” 6

To elaborate:

- The premises of Canadian Aboriginal law, as it is being practiced in Canada’s contemporary legal and political landscape, are an attempt to bring Indigenous Peoples under the jurisdiction of Canada’s liberal democratic legal and social order. They define Aboriginal rights and title without connection to Indigenous laws or social order.7

- [It is a] process of forcing one kind of conception of legal interests into forms defined within another legal system … [which is] then further confined … [to limit the scope of any Aboriginal rights] that might touch on non-Aboriginal interests.8

Christie argues that one of the “pulls” in Canadian law as it applies to Indigenous people is institutional. The Supreme Court of Canada is created within a liberal democratic social order. The authority of the court system is predicated on uncontested Anglo-Canadian sovereignty. Courts are drawn to answer to the interests of that sovereignty. They are naturally inclined—if not to maintain the status quo—then at least to protect it as much as possible, jurisprudentially.9

Yet contested sovereignty has always been at the heart of Indigenous resistance to the colonial project.10 Pluralism would therefore seem to require, at the least, shared sovereignty. It would then have to find ways to address inevitable jurisdictional overlap. Under Canada’s present constitutional doctrines, when all else fails, the federal law is paramount. The trouble with paramountcy in any possible three-fold division of powers is the premise of a so-called “senior government.” That returns everything back to the question of who is ultimately sovereign.

Toward the end of his article, Christie proposes that law reform must work from what he terms “strong pluralism.” That kind of pluralism would allow First Nations to assume the “broad powers of governance that would permit them to fashion their own institutions and work out their own solutions to social, economic and political problems.”11

Having read his book and article now twice, I am persuaded Christie is right in this respect.12 Independent Indigenous self-government is a necessary corrective to past and present injustice and inequality, as well as the only principled way forward.

Implementing the UNDRIP Acts through strong pluralism would therefore result not only in a braiding of legal systems but the creation of a series of parallel legal systems, each with its own court, First Nation by First Nation, right across the province.

Public policy

There would be howls of protest along the way, such as those which greeted the now-aborted BC Land Act amendments.13

There would also be a myriad of practical difficulties given the sheer number of Indigenous Peoples in British Columbia.

But the most difficult challenge may lie in the overwhelming plurality between, among, and within Indigenous groups themselves—and in the fact that their present-day social and political ordering and consequent financial aspirations reflect a broad range of often-conflicting views.14

One example of intra-Indigenous contention is the Haisla Nation’s decision to work toward healing and restoration of the well-being of their people by investing in a liquified natural gas partnership in their territories. As Dallas Smith, chair of Coast Funds, points out in his foreword to a remarkable recent book of stories of Indigenous leadership, resilience and connection to homelands,15

… many Indigenous Peoples, including the Gitga’at, the Hailzaqv Nation, and the Council of the Haida Nation, have fought strenuously against oil and gas development in or potentially affecting their [own] homelands. They have done so both in court and on the front lines of protests against heavy industrial development in their territories. The painful consequences of [such] opposing forces continue to be writ large in terms of damaged relationships and disputes between the Nations and individuals involved.

Many other examples come to mind, most prominently in relation to the gas pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territory. Damage and pain.

The underlying conflict is this.

On the one hand, it might well be said that having a pro-development mindset brings to completion the colonization project and constitutes the ultimate psychological assimilation into an Anglo-Canadian world view.

On the other hand, there are elements of human reality in all of this. Like anyone else, Indigenous people naturally want the benefits of material wealth, and who can blame them? Few would realistically advocate a return to a subsistence culture, living off the land, rebuilding villages instead of high-rises on the traditional lands next to the Burrard bridge. Why should anyone—and in particular, non-Indigenous Canadians—expect some sort of artificial cultural purity, with Indigenous people who wish to honour tradition having to eschew the efficiencies and advantages of contemporary life.

The BCLI’s pluralism project would thus have to reconcile a plurality of pluralities.

Politics

I frankly wonder if anything close to the strong pluralism posited by Professor Christie could ever gain acceptance among Canada’s and British Columbia’s elected legislators. Yet, once started down that road to Aboriginal law reform, there would be huge harm to credibility and the prospects of reconciliation if BCLI or the government resiled from its seeming promises.

The latter has already started happening, in a smaller way on another front. In February 2024, John Rustad, leader of the revived BC Conservative Party and its sole MLA, proposed that British Columbia repeal its UNDRIP Act and seek a definitive answer on the issue of Aboriginal title through the courts. That may have been prompted by the Land Act amendments; and it also may have been a desperate attempt to achieve electoral advantage by appealing to a nascent anti-Indigenous backlash among British Columbians of a certain persuasion.

Since February, there have been political developments. The present NDP government has re-invigorated its movement toward the implementation of UNDRIP by (among other things) confirming Indigenous title to Haida Gwaii. Mr. Rustad is now leading a party that may become His Majesty’s Official Opposition, if not the new government.16

Repudiating UNDRIP principles and by necessary implication the human rights and dignity of Indigenous people will only serve as an accelerant to fear, uncertainty, racism, and hatred in our province. There is a real risk to all parties in allowing UNDRIP to become a wedge issue in the upcoming 2024 provincial election.

De Facto Indigenous Sovereignty

For some time, I have been vacillating in my own thinking between and among the various possible ways to give effect to Aboriginal law reform in British Columbia. I have now come to the view that our best hope lies outside the realm of reform pursued through an Anglo-Canadian legal lens, with all its challenges and divisive dangers.

I think there can be a better way, through recognizing a common humanity and commonality of interest between and among Canada, the provinces, Indigenous Peoples and all the various groups and individuals affected by their respective acts of governance.

That better way involves using Indigenous conceptions of law to inform the meaning of sovereignty: that is, determining what’s right and what’s wrong in relation to the natural world and all its inhabitants; and conducting oneself in a good way in those relationships, for as long as the sun shines, the rivers flow, and the grass grows.17

In case that seems romanticized and unrealistic, let me offer two tangible examples of what I mean.

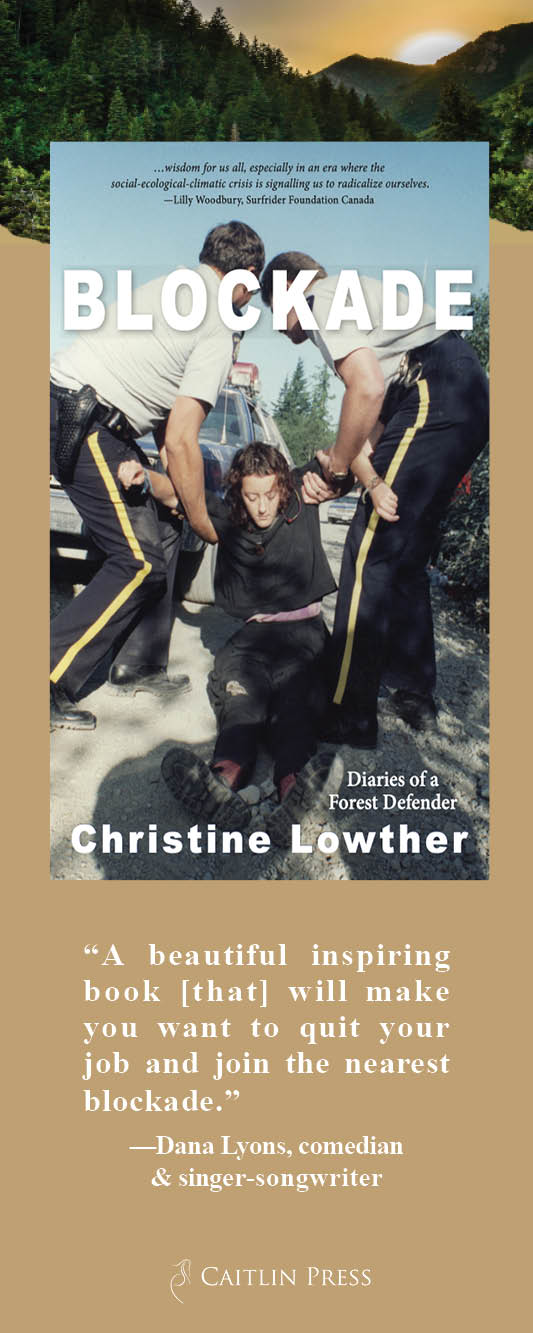

Fairy Creek

The first example is what happened in response to the dispute over old growth logging at Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island.

In August 2020, environmentalists set up a blockade to stop the logging of old growth cedar by a joint venture that included local First Nations.

According to media reports, the Pacheedaht First Nation, in whose traditional territory Fairy Creek lies, was internally divided on the issue. “It would devastate the economy if we lost old growth,” one worker said, referring to environmentalists’ calls to ban the practice. “You’re not going to find a $31-an-hour unskilled job on the island without forestry.” On the other hand, Pacheedaht elder Bill Jones supported the blockades and said protesters were there at his invitation. He accused the band council of “thinking the forest is a commodity.”

Protests wore on. In early June 2021 came two substantive acts of Indigenous governance.

First, the three Nations involved signed the Hišuk ma c̕awak Declaration, asserting that third parties must respect their governance and stewardship responsibilities, their sacred principles, and their right to economically benefit from the resources within their ḥahahuułi.

The following day, the three Nations gave formal notice to the Province of British Columbia to defer old-growth logging for two years.

The Fairy Creek example, along with others, shows how some First Nations have a remarkable aptitude for the cut and thrust of modern governance. Moreover, based on that example, affected British Columbians can seemingly be confident that an Indigenous counterpart to the “honour of the Crown” will apply.

The story of Snxakila

What really animates the drive for Indigenous sovereignty is the desire of human beings to reconnect with traditions and values inherent in the land itself—to heal themselves psychologically and not only financially.

The story of Snxakila (Clyde Tallio) in chapter 1 of This Place is Who We Are provides my second example of how to achieve that goal without the formalities of law reform.18

Snxakila was born in the Bella Coola valley and raised in the reserve village of Q’uml’uts in Nuxálkmc, the traditional territory of the Nuxálk Nation.

The chapter tells of his nineteen-year personal journey toward stl’mstaliwa’—coming to be physically, emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually balanced, not only within himself but with the environment around him. It is a way of understanding who he is “as a Nuxálkmc human being [and] the landscape in which he and his fellow Nuxálkmc citizens and their ancestors have lived and thrived for millennia.”

When Snxakila now goes out into Nuxálkmc as a working adult, he sees all that history and feels it within himself—part of a

continuous connection … that only a Nuxálkmc can truly understand: that connection we feel to our lands, our waters, our territory, and the responsibility that goes with it…. Walking that path with our traditions, our teachings, our world view, and our language allows us to understand what it means to have that full human experience, stl’mstaliwa: to be Nuxálkmc and what it means to walk in this world.

Snxakila says he is determined to do whatever he can to help restore the well-being of Nuxálkmc from the depredations of colonialism and “help his Nation regain self-determination, regain their rights and their connection to their land in ancestral terms, free of non-Nuxálk interference and control, and to exercise original, ancient stewardship roles and responsibilities in Nuxálkmc.”

His personal journey toward stl’mstaliwa’ has become a platform for work to gather the Nation’s collective knowledge, laws and practices, in particular relating to sputc (eulachon). That knowledge was collected in a 2017 book, Alhqulh Ti Sputc, which describes ancestral governance roles and practices in relation to sputc and all aspects of community and territorial well-being connected to its care, harvesting and use.

The book had its origins in 1997 when, after successive years of plenty, the sputc runs dramatically declined in the local rivers. For the ensuing decades, no fish at all returned. There was no help from government. That spurred a call to action in the mid-2010s to put back into active practice the laws, ceremony, roles, and stewardship regime that had always been the foundation of the Nuxálkmc management and use of the sputc. As Snxakila says, “Everyone firmly believed that the sputc would return in their former glory one day. This work would be vital to ensure that people would be ready when they did….” And, starting in 2018, they did begin to return.

According to Snxakila, the book was “momentous and empowering” — the first literary encapsulation of Nuxálk oral tradition “undertaken by Nuxálkmc for Nuxálkmc … [providing] a foundation for upholding Nuxálkmc stewardship authority, learning about sputc practices and applying Nuxálkmc knowledge to restore and protect.”

It was also an impetus for a new broader governance project, including the collection of other Nuxálkmc foundational teachings and laws, to “give more strength to all the work we want to do to regain our autonomy over our territory, and our sovereignty. …[U]sing western governance is not helping us reach the results we want. What we need to survive and function as a community, as a Nation, is to be rooted in our traditions and our world view.”

Snxakila clearly means “sovereignty” viewed through an Indigenous lens. He explains that

[while Canadian law] is very unnatural and very forced [,] Nuxálkmc law is livable. It is a way of encouraging the good things in life to appear and to be prepared for the bad things, and to have preventative measures and awareness. … [It also requires] being good caretakers … having a culture based on sustainable resource management practices.

He continues:

Embracing stl’mstaliwa means we must live with purpose. We must take care of ourselves and of our lands and waters and sustain them for the next generation. We call that work nuyalcalhlayc and putl’alt, which translates to ‘clearing the path’ and ‘to think of those not yet born.’ How do we as Nuxálkmc live our traditions and by doing so clear the path and help support the next generation?

The opportunities, he says, “are brilliant:”

Applying our traditional practices in this way is part of reaching that balance as human beings. It validates our collective ancestral rights as a people. It helps us understand our connections to the land and our culture and history and gives us strength to withstand all the other issues we still face as a result of colonization: the systemic poverty, the encroachment by industry on our sacred lands, and the healing we need to do. If we apply this kind of approach to everything we do, it will be the medicine that heals us.

Those are powerful thoughts and inspiring prospects. Could the same reasonably be expected as the likely outcome of formal Aboriginal law reform based on Anglo-Canadian legal principles and uncertain notions of pluralism? As previously noted, I have my doubts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, and in answer to the potentially dangerous futility of pursuing Aboriginal law reform solutions through the UNDRIP Acts, what happened at Fairy Creek and is happening in Nuxálkmc and elsewhere in BC suggests there may in fact be no need to resolve nice points of legal jurisdiction, now or ever.

Those examples of principle, pragmatism, and a lived vision of constitutional law show how to give effect to Indigenous self-government through honour and mutual respect, without the need for formal legal re-ordering.

The examples should give us all confidence enough to grasp the nettle of de facto Indigenous sovereignty and get on with what really matters—alleviation of Indigenous people’s poverty and accelerated enhancement of Indigenous Peoples’ opportunities for healing both themselves and our shared world.

*

Richard Butler lives on the traditional territory of the lekwungen-speaking Peoples, a retired lawyer and sometime law professor, and more recently a writer on various Indigenous subjects. He is the author of Taking Reconciliation Personally, I Dare Say… Conversations with Indigeneity, and the new title What Is This? Who Am I?: Culturally Informed Appreciation of Coastal Peoples’ Artworks, published through A & R Publishing, and recently reviewed the published work of Karen Duffek, Bill McLennan, Jordan Wilson (eds.), C.P. Champion and Tom Flanagan (eds.), and Aaron A.M. Ross for The British Columbia Review.

- Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act SBC 2019 c. 44. ↩︎

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act SC 2021 c. 14. ↩︎

- [i]https://www.bcli.org/latest-reconciliation-primers-explore-legal-pluralism/ . ↩︎

- Gordon Christie, “Indigenous Legal Orders, Canadian Laws and UNDRIP,” in John Borrows, Larry Chartrand, Oonagh E. Fitzgerald and Risa Schwartz (eds.), Braiding Legal Orders: Implementing the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Centre of International Governance Innovation (2019), pp. 47 ff. (“Christie article”). ↩︎

- Gordon Christie, Canadian Law and Indigenous Self-Determination: a Naturalist Analysis, University of Toronto Press (2019) (“Christie book”) ↩︎

- Christie article, p. 48. ↩︎

- Christie book, p. 75. ↩︎

- Id. p. 79. ↩︎

- Id. pp. 110, 115, 126. ↩︎

- For further reading on the issue of sovereignty, see Michael Adams, “Towards Reconciliation: A Proposal for a New Theory of Crown Sovereignty,” 2018 CanLIIDocs 11052; Kent McNeil, “The Source, Nature, and Content of the Crown’s Underlying Title to Aboriginal Title Lands,” 2018 CanLIIDocs 176; Mitchell v MNR, discussed in the Christie book, at p. 241 – 242; and Ryan Beaton, “De facto and de jure Crown Sovereignty: Reconciliation and Legitimation at the Supreme Court of Canada,” 2018 CanLIIDocs 11052. ↩︎

- Christie article, p. 50. ↩︎

- The essentials of his argument may be extracted from the following pages of the Christie book: 85, 88, 126, 133 -135, 153 – 154, chapter 5, and especially 326 – 332, 345 – 347, 353 – 354, and 360 on modern treaties. ↩︎

- https://www.timescolonist.com/opinion/comment-much-ado-about-nothing-land-act-amendments-are-small-step-on-a-long-path-8214895 ↩︎

- See “Turning Away from the State: Cultural Appropriation in the Shadow of the Courts,” in John Borrows and Kent McNeil (ed.), Voicing Identity: Cultural Appropriation and Indigenous Issues, University of Toronto Press, (2022), chapter 9. Christie also notes the divergence between and among different Indigenous collectives, not only in forms of governance but also in concepts and understandings of such things as sovereignty, governance, nationhood and territory which are “unique and peculiar to Indigenous understandings (and widely variant across time and place)” Christie book., p. 122. ↩︎

- Katherine Palmer Gordon, This Place is Who We Are: Stories of Indigenous Leadership, Resilience and Connection to Homelands, Harbour Publishing (2023), p. 13. ↩︎

- In April 2024, the BC government entered into an agreement recognizing that the Haida Nation had aboriginal title to all Haida Gwaii. That seems to have been an act of political courage, contradicting what I would have predicted. Yet it is still uncertain exactly what will be involved in ceding title. The Devil will be in the details. But it will certainly not involve a ceding of sovereignty; and it may turn out to be a version of what Anthropologist Elizabeth A. Povinelli, referring to recognition laws respecting Australian Aboriginal Peoples, described as “the cunning of recognition”: see Jennifer Kramer, “Fighting with Property: the Double-edged Character of Ownership,” in Charlotte Townsend-Gault et al (ed.), Native Art of the Northwest Coast: a History of Changing Ideas (UBC Press, 2013). ↩︎

- See John Borrows et al (eds.), in Braiding Legal Orders: Implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples supra footnote 4,p. 2.; “Earth-Bound: Indigenous Resurgence and Environmental Reconciliation,” in Michael Asch et al (eds.), Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings University of Toronto Press (2018), chapter 2 and p.53 – 56. ↩︎

- Palmer, supra footnote 15, chapter 1 ↩︎

2 comments on “An exercise in futility”

An excellent summary of the reality of aboriginal law reform. I would only remark that there seems to be an incomplete understanding of the complexity of the Western legal tradition. When Aldo Leopold formulated his famous ethical dictum: ‘A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise,’ he does not do so in a vacuum. He does so from a long western tradition. If we are to reconcile, “settlers” have to recover that overlooked common cultural ground, which they share with First Nations.