The wars: before, between, after

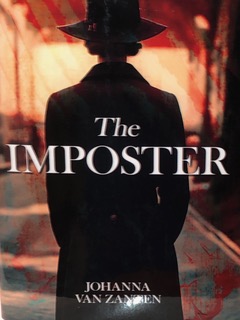

The Imposter

by Johanna Van Zanten

Las Vegas: Histria Books, 2024

$29.99 / 9761592113767

Reviewed by Valerie Green

*

Johanna Van Zanten has created an intriguing story spanning two World Wars in Europe in her second novel The Imposter.

Like her first novel (Between a Rock and a Hard Place) The Imposter explores the overwhelming decisions that must be made when one’s true heritage can destroy family relationships and cause pain and division between a mother and her children.

The story begins when the protagonist, Johanna, born in Germany in 1881, is now lying on her death bed and approaching one hundred. Her confused mind is looking back over her long life and acknowledging the mistakes she made along the way.

As the daughter of Friedrich (Fritz) and Friederike Manske, Johanna lived in Osterode, Germany where her Vati was a shoemaker. To help with the family income, Johanna’s Mutti worked in a funeral home.

Fritz, however, had been born in Pomerania, then part of the Prussian Empire on the Baltic Coast, and because of this Polish ancestry, Johanna found herself looked down upon. She was not “pure German” as she longed to be and from school age, she discovered that Polish people were often scorned. She could not understand why she was called a “dirty Polak” by schoolmates. So, as a curious child, she set out to ask her parents numerous questions and why her father had tried to hide his background. She continued this questioning when her Ur-Opa (great-grandfather) came to live with them. She already knew that her father had changed his name when he came to Germany at the age of sixteen, to make it sound less Polish and more German. She had been told never to talk of the name change.

As the story of Johanna’s early years unfolds, we also learn more about her family—she shares a bedroom with her older sister, Rieke, and her younger sister Hannah. She also has two brothers, August and Wilhelm (Willi). Watching how hard her parents worked every day to make a living and raise their five children, Joanna decides she was not “cut out for having children and working from morning till evening. That’s no life.” “How did her parents put up with it?” she wondered.

Her parents were tough people and rarely showed their love for the children. On one occasion, the author mentions when Friederike briefly touches Johanna’s face: “it was an unusual gesture. She wished Mutti would touch her face more often.” A simple sentence that gives the reader insight into the hard character Johanna is perhaps forced to become as she grows older and continues this coolness with her own children.

On her sixteenth birthday, Friedrich tells his daughter something else about her family. But she pushed it “deep down and filed it away as irrelevant information.” All her life she “professed to be one-hundred percent German, an Aryan….” and she had ached to be treated as such with respect. She tried hard to ignore the stigma of her father’s mixed heritage. And later she also realized her mother’s ancestors were Jewish. All of this she ignored in her need to be considered pure German.

Though Johanna wants something more from life, she is forced to accept a job as a housemaid. She loses this job when the master of the house tries to rape her, and she spurns him. By the time she is twenty-three, she accepts an unusual job as a concession shop operator with the railroad. The job enables her to leave home and travel. She sets up a concession shop for the rail yard workers, and her future home in an empty passenger railcar.

Up until that point in the story, we are told much of the history of the German Empire through Johanna’s observations that, although interesting, often reads more like an historical non-fiction book. Now, however, the story really picks up when she meets the love of her life, Hendrik, who is Dutch and the construction superintendent on the railroad. They fall madly in love and, although she had vowed not to settle down and have children and live a hard life like her parents, Hendrik and Johanna marry. Through lack of adequate birth control, she and Hendrik soon welcome five children.

During that time, the growing family stayed in their make-do carriage home alongside the concession shop for the workers. But the situation soon becomes untenable. While Hendrik continues to promise they will soon move to his family farm in Holland and settle down, when that doesn’t happen Johann makes the decision to move with her children into town. Hendrik keeps his job and visits only on weekends.

Eventually with war approaching in 1914, Hendrik finally realizes they must escape to Holland and now Johanna’s loyalty is really put to the test in a powerful way. Which side is she on? Is she Polish, German or Dutch? Or is she just an imposter?

Kelowna resident Van Zanten’s characters are all strong and she enables her readers to see all sides of the coin during those troubled European war years. The invasion and occupation of Holland by the Germans in World War II is perfectly portrayed in this book, as are the conflicting feelings of Johanna and Hendrik and Joanna’s family back in Germany. Following the death of her beloved Hendrik, she must make her own decisions even though she took Dutch citizenship.

With Germany’s economy foundering after the First World War, it is easy to see how Adolph Hitler’s dream for a superior Germany could dazzle his followers. Even Johanna was inspired by his words. But by 1939, with her own children being adults and fighting with the Allies, her own family fighting for Germany, and her younger son, Robert, helping her to supply farm supplies to the Nazis occupying their country, life becomes unbearable for her. She learns that some members of her family might even be part of the Resistance. But where does she belong?

To help her cope with loss and the confusion of her life, she begins to drink more. The occasional schnapps or glass of sherry becomes a daily occurrence to enable her to sleep and get through each day. Johanna’s character will convey both anger and compassion to readers. They will feel both emotions as they follow this pathetic, arthritic, alcoholic woman through the last years of her life as she finally realizes that Hitler’s horrific “Final Solution” was the most odious event in history.

*

Valerie Green was born and educated in England, where she studied journalism and law. Her passion was always writing from the moment she first held a pen. After working at the world-famous Foyles Books in London (followed by a brief stint with MI5 and legal firms), she moved to Canada in 1968 and embarked on a long career as a freelance writer, columnist, and author of over twenty nonfiction historical and true-crime books. Hancock House recently released Tomorrow, the final volume of The McBride Chronicles (after Providence, Destiny, and Legacy). Now semi-retired (although writers never really retire!) she enjoys taking short road trips around BC with her husband, watching their two beloved grandsons grow up and, of course, writing. [Editor’s note: Valerie Green has recently reviewed books by DL Acken and Aurelia Louvet, Carly Butler, Daniel Kalla, John Delacourt, Laurel Dykstra, Andrea Warner, and J.T. Siemens for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “The wars: before, between, after”