Appreciating where we are

Fried Eggs and Fish Scales: Tales from a Sointula Troller

by Jon Taylor

Madeira Park, Harbour Publishing, 2024

$24.95 / 9781990776656

On the Trail: 50 Years of Engaging with Nature

by Langley Field Naturalists

Surrey: Hancock House, 2023

$19.95 / 9780888397591

Gumboot Guys: Nautical Adventures on British Columbia’s North Coast

by Lou Allison and Jane Wilde (eds.)

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2023

$26 / 9781773861180

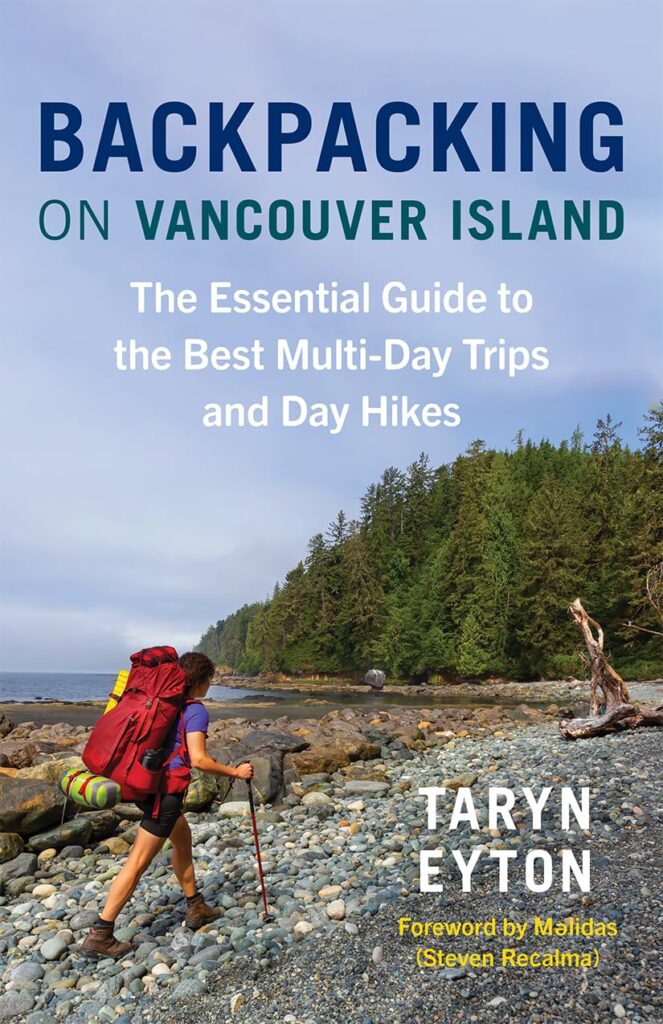

Backpacking on Vancouver Island: The Essential Guide to the Best Multi-Day Trips and Day Hikes

by Taryn Eyton

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2024

$26.95 / 9781778400100

Review omnibus by Stephen Hume

*

Raymond Patterson, who died in Victoria in 1984, had been cued for a banking career but left London a hundred years ago to spend his life personally exploring and writing about the vast and remote British Columbia interior.

One of his tales mentions how one morning paddling an overgrown northern snye – that’s the back channel of a river where it curls behind a small island – he heard singing. Around a bend, poling his own canoe, came a Vancouver Sun reporter in search of a story in the Omineca gold rush camps.

That anecdote contrasts with an aphorism from Dene trapper Ted Trindell, who took me up Patterson’s “Dangerous River,” the Nahanni. He commented on what he called “the 99-50 club” – the 99% of urban folk who never get more than 50 yards (yes, yards, Ted never cottoned to metrics) from the paved road.

As a long-time Vancouver Sun reporter myself, and one who had the lifelong joy of chasing stories beyond the end of the pavement, often beyond the gravel and frequently beyond the end of the marked footpath, Ted’s observation resonated.

So many of us travel the world to see its wonders yet seem curiously ambivalent to the wonders that begin just beyond the city limits.

I suspect this is a cultural and social artifact of the colonized mind in a colonial culture; the archetypal certainty that elsewhere is always superior to here and that even those of us who were born into settler culture here can’t escape the sense that our ancestral origin thereis more valid and validating in some way.

The architectural landscape we inhabit, for example, is saturated with the iconic imagery of elsewhere, a pervasive colonizing of the native landscape with otherness.

Buildings – official, commercial, private – hearken back to Greek temples, Roman pantheons, Confucian gardens, Japanese tea houses, Italianate courtyards, Georgian mansions, Irish pubs, Spanish haciendas, Russian villages, Bavarian beer gardens, Indian domes, and Swiss chalets. There are Ionic columns and Bauhaus blocks, crenellated faux-medieval armories and schools, Gothic church spires, Cape Cod dormers and American colonial revivals, plantation porticoes, and Victorian gingerbread.

Thus, it was that I recently found myself digging through the fascinating statistics compiled recently by one of B.C.’s leading vendors of travel insurance – want to find out what’s really happening, turn to the actuaries – where I came across one of those small facts that reverberates with the anecdotal assumptions.

If, as Ted Trindell so wryly observed, looking up from the drift anchor he was fashioning for our canoe with a camp axe and a rusted-out bucket, it seems like most Vancouver-dwellers have seen little of their province and don’t much care to go to the trouble, the researchers tabulating who buys travel insurance for what destinations confirm it.

They found that 76 percent of Vancouverites planning vacations in 2024 plan to travel outside British Columbia. Also, while 82 percent expressed an interest in ecotourism, it wasn’t here they were interested in experiencing, it was somewhere else. Preferably an add-on to the orthodoxy of trips to soak up exotic culture, history, hike pilgrimage routes, visit religious shrines, and collect trophy destinations from the Amazon to Zanzibar.

Each year, Canadians make about 28.5 million vacation trips to the United States, Europe, Central America, and Asia.

Yet surrounding those of us who can’t wait to hike in a Costa Rican cloud forest, to overrun Greek islands or so-flood the street cafes in Barcelona and Provence that locals are rising in revolt, is a landscape that’s as vast, unique and saturated with marvels as anything we’ll find on a curated tour in Paris, a walking tour in Wales or an ad hoc trip to Kyoto, Hong Kong, or Rome.

British Columbia is roughly the size of France, Germany, and England. It’s three times the size of Italy. It’s a third the size of India. It’s bigger than California, Oregon, and Washington – the entire West Coast of the Lower 48 states of the USA – combined.

It’s home to 10,000 years of rich human history. There are more than 200 First Nations in B.C. each with a profound legacy of art, history, legend, and myth. For all those who journey to see the battle sites at Hastings or Agincourt, few visit or even know about Dimlahamid or Maple Bay. Camino de Santiago in Spain gets 250,000 hikers a year, the hike to Della Falls, eight times higher than Niagara Falls, a few.

B.C.’s astonishing landscape is one of the most complex, complicated, and diverse both within Canada, on the continent, and in the wider world.

There are 16 bio-geo-climatic zones in B.C. Six of these represent the maximum global range for the plants, animals, and geological features of the individual zone. Some of them – for example, the dry belt coastal Douglas fir habitat on the east coast of Vancouver Island and the adjacent Gulf Islands – are among the rarest on the planet and yet they sustain the most diverse web of life in Canada.

B.C. has the greatest range of animal, insect, and plant species in the country – 50,000 species – and that’s excluding single-celled organisms. Of these, only about 3,800 have been assessed to determine conservation status and 43% of those warrant concern. Of the species found in B.C., almost 100 represent largest global range for that species.

It’s been said that Dolomite Narrows in Haida Gwaii is one of the most biologically diverse places on earth for different species found per square metre. You can see cactus bloom on the arid islands between Vancouver and Victoria, watch the snowfields turn red with a rare algae bloom above Comox and, if you’re lucky, see the white “spirit bear” or watch grizzlies the size of small cars in the rainforests of the mid-Coast.

That diversity extends from the biological realm to the geophysical. Ten mountain ranges descend almost 10 kilometres from alpine to abyssal plain. These mountains are carved by vast rivers. Their drainage zones are the size of entire European countries. B.C. is the most variated region in Canada for terrain, for climate, altitude, weather. Here are found the hottest, coldest, wettest, driest, and snowiest places in the country. Hucuktlis Lake near Port Alberni recorded nine metres of rain in 1997; Ashcroft measured but 208 millimetres in all of 1938. Summer temperatures near 50 degrees – that’s the temperature at which your steak approaches medium rare on the barbecue — scorch Lytton in summer; winters at Smith River in the North, temperatures fall to near 60 below zero, cold enough that when you speak, the exhaled breath of your words falls as snow.

There is antelope desert with scorpions, oozing coastal pine bogs, alpine tundra, temperate rain forest where the trees are 120 metres high and 2,000 years old, and impassable jungles of Devil’s Club. There are lava beds and ice fields – B.C. has more than 50 active volcanoes, many of them submarine – huge seismic faults on which there are annual earthquake storms. Some of the greatest earthquakes in world history have occurred here.

Also, there’s human diversity, in addition to First Nations there are nearly 40 other distinctive ethnic groups in the province and, in addition to the 35 indigenous languages, almost 1.5 million British Columbians report a language other than English or French as their first language.

There’s an entire library of books about the marvels of a province that so many put at the bottom of their vacation bucket lists, certainly too many to cite here. But a few recent titles in the not-so-often-reviewed list caught my eye. These may seem like humble offerings in the province’s extraordinary literary pantheon, but like many of the gems in the vast, tumbled landscape and its dishevelled, contradictory and often counterintuitive social history – who’d-a-thunk stereotypically starchy Vancouver Island provided Canada’s only Black Father of Confederation, elected the first Jews to any provincial legislature (and to Canada’s parliament), and then produced the first female cabinet minister in the British Empire?

*

On the Trail: 50 Years of Engaging with Nature is a collaboration by 11 members of the Langley Field Naturalists and it’s simultaneously an eloquent celebration of the resilience, tenacity, and richness the natural world that endures in the midst of Canada’s emerging West Coast megalopolis, a call to arms for citizens determined that it prevail for future generations, and a powerful reminder that even in the controlled climate of a downtown high-rise we’re just a public transit ride from what makes B.C. such a unique and praiseworthy place.

For half a century, Langley, once a tiny trading post past which Cowichan war canoes paddled with the heads of their enemies hanging from the bows, has been at storm centre of landscape modification, from wild alluvial flood plains and gloomy forests to cow pastures to cloverleafs and condo tracts.

Into this headwind stepped the Langley Field Naturalists, a loose collection of birdwatchers worried about declining screech owl populations in the face of urban encroachment, wildflower enthusiasts excited by Hooded Ladies’ Tresses and Spotted Coralroot, both native orchids, old timers who had watched stream after stream vanish into culverts and conduits and thought some habitat should be preserved for salmon, even a couple of reporters, Larry Rogers of the Vancouver Sun and Tony Eberts of The Province.

They had informally succeeded in championing creation of the Campbell Valley Regional Park and formally organized in 1973. Their vision was preservation of what remained, restoration of what could be restored – watersheds, wetlands, lagoons, woodlands, and meadows — and monitoring the health of natural places amid the development boom. They did streambed rehabilitation and organized raptor counts – almost 9,000 over the last 25 years, including a Golden eagle and a snowy owl from the Arctic.

Half a century later salmon are once again spawning in the Little Campbell River and one of the Langley Field Naturalists’ key objectives is bearing fruit – establishing the value of these native landscapes as an educational tool for the rising generations that will inherit them.

“There are moments when naturalists feel a deep connection with nature, when time stands still, when the cold or the rain or the snow no longer matter. When your eyes suddenly, unexpectedly, meet the eyes of a hawk or an eagle or owl (that has probably been watching you for some time). Yes, that can be one such moment,” the writers observe.

So, for a reader, is the unexpected encounter with a little book like this which encompasses entire hidden worlds between its covers.

The writing is as plain and unadorned as a well-used axe handle: easy, accessible, and unpretentious as the Langley Field Naturalists and the humble yet ambitious quest the organization addresses.

*

Equally unpretentious and a thoroughly entertaining armchair adventure in B.C.’s exotic hinterland is Gumboot Guys: Nautical Adventures on British Columbia’s North Coast. This series of mini memoirs – brief self-described sketches of life aboard 40 different vessels ranging in size from cedar-strip canoes to 650-tonne steel-hulled trawlers and from sailboats that sink at dock to aluminum power boats that pound themselves to pieces in rough seas to be abandoned on the beach – is the third in a series from Prince Rupert chroniclers of coastal life, Lou Allison and Jane Wilde, who have the distinct advantage of having lived it.

The series began with Gumboot Girls, a 2012 chronicle of a demographic coming-of-age event half a century ago in which young Baby Boomers leaving behind their teens hit the road for The West, like generations before them, and wound up at the end of it – where the pavement (and in many cases the gravel) peters out on B.C.’s fog-draped, storm-lashed North Coast.

Some didn’t stop there but became deckhands, live-aboards, skippers and cabin companions on B.C.’s then vast fleet of offshore salmon trollers, gill-netters, purse-seiners, prawn boats, and halibut longliners.

Gumboot Girls told the previously untapped stories of a generation of young women that infused the traditional male narrative of Far West discovery and self-discovery. Dancing in Gumboots, published in 2018, took the narrative to Vancouver Island and the adjacent Gulf Islands. It was a place where girls on remote island homesteads would once pack their dresses in a duffle bag, row all day to Cowichan Station – which had the only sprung dance floor on the West Coast save for San Francisco – to attend a ball thrown for the crews of visiting Royal Navy warship, dance all night, then change back into their dungarees and row home.

Gumboot Guys adds the male component to the great migration from Ottawa, Toronto, the Prairies and Quebec. In these tales you’ll meet British university professors who sink their boats, ski bums looking to finance another winter at Marmot Basin or Mount Norquay, teenagers drifting in search of something, anything really, to give definition to their lives and finding wives and starting families, American draft resisters. The Tsimshian, who have been there since time immemorial, have a warmly bemused term for the newcomers – cumshewa; driftwood.

You’ll meet their boats — Argo and Azurite, Child of the Moon, and Toker II, Oona R and Pansy May – each one as much a character in the narrative as the story-tellers and their search for safe moorage, the million-dollar herring set, or just an abandoned wheelhouse they can salvage from a hulk to replace the one on the rotten boat they are eternally rebuilding.

It’s a book deeply infused with nostalgia for a time and a way of life vanishing from the coast that once sustained it and a valuable contribution to this history of what quintessential B.C. writer Terry Glavin has so aptly called This Ragged Place.

It is indeed so. The B.C. coastline that remains invisible to most residents of Vancouver except as a cloud-shrouded outline seen from 20 kilometres up on flights to and from some other place is roughly equal to three-quarters of the Earth’s circumference at the equator.

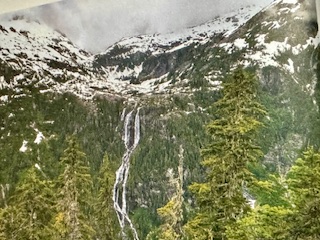

Huge tides and storm surges crash through and around this convoluted, intricate almost 30,000 kilometre maze of fiords, headlands, more than 6,000 islands and islets, inland seas, and sea mounts that tower three kilometres from the abyssal plain without breaking the surface. Frigid rivers plunge four kilometres down into the inlets from glaciers and snowfields on peaks like Mt. Waddington, Stiletto, Monarch, and Damocles.

There are tide rips and overfalls so powerful even killer whales avoid them, tidal surges like Skookumchuk Narrows where the currents reach 16 knots and Seymour Narrows where giant whirlpools can fire whole tree trunks into the air like breaching whales, and frequent Marine Bombs, sudden fast-moving storm cells like the one in 1975 that unexpectedly caught the entire Pacific herring fleet, sank 12 boats and drowned 13 crew or the one that followed in 1984 and caught the halibut fleet at sea, sinking six boats and drowning five of the 16 crew thrown into storm swells the size to two-storey houses.

*

If Gumboot Guys provides a sketchbook of life on this forgotten seascape that seems to oscillate between the disastrous and the divine, Fried Eggs and Fish Scales: Tales from a Sointula Troller provides the unredacted version, a full-on depiction from Jon Taylor.

Like many another in the great westward migration 50 years ago, Taylor was farming in Alberta when he took a trip to Malcolm Island in 1975. He’d heard about the place from his grandmother who saw and abandoned the idea of settling there in 1917.

Sointula had its origins as a Finnish socialist utopian commune founded in 1901. It foundered when the guy who started it thought introducing free love would be a great innovation. He soon discovered not everyone – particularly the women – agreed with his vision of paradise. The utopian ideal went up in smoke in 1903 when a fire burned the communal hall killing 11 of the 127 citizens and destroying all the colony’s supplies. The utopia failed in 1905. Many stayed on to fish – indeed, the drum-hauled gill-net that revolutionized West Coast salmon fishing was invented there and the oldest co-op in B.C. still operates there – or log.

Sointula remained a quirky, myth-laden outpost, a kind of eccentric and laconic alter ego to bustling, commerce-minded Alert Bay, the Kwakwaka’wakw community just across the water on Cormorant Island and to Port McNeill, defined by industrial logging, and a giant copper mine on adjacent Vancouver Island.

When I first visited Sointula more than 50 years ago, bumming a ride with a gill-netter leaving Alert Bay in the early morning mist, I was offered breakfast – half-a-litre of almost-sour milk with half-a-litre of Kahlúa poured into it. The memory of that breakfast on the stinky, slimy back end of a gill-netter in-bound from off the Nimpkish River, sprang into vivid relief when I read the comment from retired fisheries officer Randy Nelson about Taylor’s witty, charming and disarmingly frank account of settling there and going fishing: “I used to have a jaded view that some commercial fishermen were lawless, tax-evading, hygienically challenged boozers. Turns out I was right,” Nelson observes. “Jon Taylor’s collection of hilarious and thought-provoking stories would make any wharf rat proud.”

It would indeed. No spoilers from this reviewer about Taylor’s stories of pent-up demand in dockside dives, oddballs and eccentrics (including the pretty new feminist schoolteacher sent from the Big Smoke), malfunctioning heads, the penetrating stench of stove oil and Murphy’s Law as applied to fish slime’s ability to kill a romantic moment, and the perils of fishing in the fog.

Harbour’s indefatigable Howard White is to be commended for making sure these irreverent, unrepentant recollections join the more earnest accounts of a rapidly passing – and in many ways already passed – world.

Every landscape is a palimpsest, of course. Beneath the mercurial names of changing history – pre-human habitation, pre-contact, contact period, colonial, post-colonial, whatever comes next – is the place itself, the reefs of glass sponges surviving from the Jurassic; the creeks where little girls on afternoon walks with their dad may find mosasaur bones emerging from Cretaceous sediments; the striations left in rounded mountain tops by glaciers that were two kilometers deep; the immense plume of the Fraser River spilling its lens of warm fresh water across the frigid deeps of Georgia Strait to warm storied kids’ swimming beaches on Galiano and Saturna islands 30 kilometres away.

Vancouver Island, the great primordial hump that shields the Salish Sea from Pacific storms, is a place as big as entire countries elsewhere. The Island is bigger than Wales, Taiwan, Jamaica, or Israel. It’s bigger than Sicily and six times the size of Bali. It has a history as rich as anywhere with stories that reach back at least as far as the first histories of Egypt and Sumer. Yet for many dwellers on the continent, it’s a place for weekend getaways to Victoria or Parksville or a bed and breakfast off the surfing beaches of Tofino.

*

Taryn Eyton’s book Backpacking on Vancouver Island: The Essential Guide to the Best Multi-Day Trips and Day Hikes invites walkers of all ages and skill levels to direct encounters with an astonishing variety of landforms and microclimates.

There are easy trips for seniors, folks with disabilities or simply the average largely sedentary walker for whom a long stroll on the Seawall or around False Creek would push the limits. Also there are full-on adventure hikes that mean days passing through challenging terrain. Eyton’s guide outlines 35 hiking options that range from the gentle to the challenging.

The four-kilometre trail at Helliwell Park on Hornby Island starts in a Garry Oak forest and follows a rugged, stunningly beautiful coastline through undulating grasslands out into the wind-flecked Salish Sea where tides rip around craggy outcrops of St. John’s Point. The path is excellent, the maximum elevation is about 50 metres on an easy grade and you can park at the trailhead.

Alternatively, you can paddle the roughly 35 kilometres down Great Central Lake near Port Alberni then climb the 20-kilometre trail to witness Della Falls, the highest waterfall on the North American continent, where it tumbles down a series of mighty rock faces.

Or you can travel 60 kilometres west from Port Hardy at tthe north end of Vancouver Island to a trailhead on San Josef River where there was once a settlement and post office, now long abandoned. From there, you can hike 45 minutes down a well-groomed trail to San Josef Bay, a white sand crescent where the rollers boom in, unimpeded, all the way from China 8,000 kilometres beyond the horizon. If you are still feeling frisky, just over the rocky headland to the northwest is Sea Otter Bay where there’s a good chance you’ll spot one of the iconic sea mammals brought back from the brink of extinction.

If you want something to better test your mettle, though, another trail heads north though dripping rain forest to wind-blasted Cape Scott, where there was once a thriving village that ultimately perished due to its storm-bound isolation from markets. This is the true rain coast where frequent torrential downpours ride gales off the Pacific producing what some have described as the exciting phenomenon of horizontal rain. For the truly hardy, another trail leads even farther around the north end of Vancouver Island, although it is not for the faint of heart.

For those more inclined to mountains, Eyton offers a difficult – but certainly doable by amateurs, having done it myself – route up Mt. Arrowsmith, the snowclad summit that soars into the sky between Nanaimo and Port Alberni. For those who don’t like to get too far from a bed, there are wild country day hikes close to urban Victoria, like the coast trail at East Sooke Park.

Each hike included in Eyton’s useful guide is accompanied by a route map, a trip planner which details trail segment distances between key landmarks, notes about the distinctive natural and historical features of waypoints, suggestions about other walks or visits in the vicinity and further reading resources for those who want to more fully immerse themselves.

It’s an entertaining, accessible and enormously useful book for anyone who wants to experience what, despite the 20 million passenger trips booked annually between Victoria and Vancouver, remains for many The Unknown Island more than 50 years after Ian Smith’s wonderful book about it.

*

Hopefully, encountering these new books and others like them will encourage a few more of us to re-think that trip to Santorini or Mount Snowden and to instead visit The Chasm, the Nass Valley lava beds, then limestone karst caves at Horne Lake, to hike the Juan de Fuca Trail or to just stroll through the rare butterfly habitat on Hornby Island.

*

Stephen Hume was a long-time columnist at the Vancouver Sun. He has written nine books of poetry, essays and history about the landscape of B.C., the people who live beyond the city limits and their astonishing stories, including A Walk with the Rainy Sisters: In Praise of British Columbia’s Places (2010), and Simon Fraser: In Search of Modern British Columbia (2008). He was recently interviewed for The British Columbia Review Interview Series on the subject of a sense of place and storytelling.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Appreciating where we are”

I was fortunate enough to have relocated from the big smoke to the north coast in the early 70s. A whole new way of being in the world opened to me. I was happy to share a story in Gumboot Girls and in Gumboot Guys – writing for my ex-husband, dead and gone, but happily not forgotten. The 70s really should not be forgotten, I think. Deep and lasting values were discovered and continue to guide our lives as many of the boomers keep on keepin’ on. History, indeed.