Of Nature, and human nature

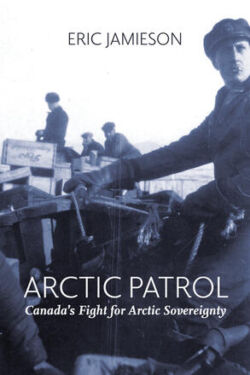

Arctic Patrol: Canada’s Fight for Arctic Sovereignty

by Eric Jamieson

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2024

$28.00 / 9781773861333

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

“The True North Strong and Free”? Most Canadians are very aware of the way in which Canada’s national identity has been linked to the evocative power of the word “north”. This resonant concept of “the north” lies at the heart of Arctic Patrol: Canada’s Fight for Arctic Sovereignty, by Eric Jamieson, award-winning author of several books of history. As any reader of this gripping history discovers, however, the far north was long an undefined territorial principle and something intensely physical: this is a book not just of boundaries and ideas, but of ice, animals—and people.

As our current news media make painfully clear, claims and counter claims over national boundaries often lead to devastating violence. It is a prompt to reflection, therefore, to consider the border disputes in the past, distant world of this book. No doubt, for most Canadians, Canada’s northern boundaries may seem somehow “natural.” Isn’t it obvious that all of the (almost 37,000) Arctic Islands between Alaska and Greenland—not to mention, of course, the northern parts of the North American mainland—should naturally be part of Canada?

Well, apparently no. In fact, virtually every page of this history is charged with the fact that, for many—both countries and individuals—the answer was for a long time a vehement “No.” How this “No” plays into a labyrinth of political manoeuvres and counter manoeuvres and how these in turn led to some astounding human feats is the fascinating stuff of Jamieson’s book.

Many readers, understandably, are likely to question the very claim of Canada’s northern “sovereignty” and land ownership, when, after all, it was the home of vital and capable aboriginals long before Europeans hoved into shivering, teeth-chattering view. For the purposes of Jamieson’s history, though, the Inuit come properly into focus only in the final—hugely important—part of the book, however crucial to many of the stories that precede it.

The word “stories” is, in many ways, an apt one. Jamieson is not just hugely knowledgeable but deft in his use of stories. In addition, rather than arranging his materials chronologically from the first days of European adventuring, Jamieson places at the core of his book stories about a special kind of “patrol” that took place most memorably in the 1920s and ‘30s.

Amongst these stories, some of them are likely to be especially fascinating to readers who know only the general outlines of this part of history of the far north. One group, for example, involves Americans—their whalers and muskox hunters, their implicit claims to large chunks of some of the largest islands, and the related question about whether Hudson’s Bay was a “closed” or “open sea.”

British Columbians who have always been irked by the American possession of the “Alaskan Panhandle” will be especially interested in the stories enlivened with colourful personalities, conflicts between Americans en route to the Yukon gold rush, and—most dramatically—good, old-fashioned “betrayal” from a Britain motivated by expedience and the desire to curry favour with the U.S.

Add to these a colourful, dubious, and self-asserting Manitoba-born American called Vilhjalmur Stefansson. His search for a “lost continent” more or less north of Alaska and, amongst other things, the deaths resulting from his ill-prepared adventuring, could hardly be better calibrated to grip modern readers.

Crucial to the way readers will respond to such information, of course, is the authorial voice. Careful, methodical, and measured, the tone Jamieson employs works because he achieves a strong sense of both reliability of judgment and depth of knowledge. In fact, as he reveals in the acknowledgements, this book is built in part from enormous amounts of original research through diaries, letters, documents, and interviews. To reflect this research, Jamieson riddles the book with endnotes and quotations from contemporaries: the author, and, in turn, the reader, benefit hugely from the fact that he has such rich sources of written material, not just official statements and unofficial comments, but also firsthand accounts from “ordinary” police officers working in the north.

Occasionally, but just occasionally, Jamieson inflects his factual writing with his own—sometimes dire—views of some of the prime players. Prominent amongst them are Stefansson, explorer Joseph-Elzéar Bernear, and Norwegian prime minster Mowinckle. Of Bernier, for example, Jamieson writes dryly of the “grandiose proclamation” he made in claiming territory for Canada, his “hubris,” and his parallel desire to have his “ego stroked.” Of the Norwegian, similarly, the author writes that the prime minister’s “jab at Canada smacked of nothing more than sour grapes” and adds that “Norway’s thirst for small foreign islands was unquenchable.” It is Stefansson, though, who stirs the author to his strongest language, and especially about the “trail of controversy and tragedy” he created. As he argues of an especially disturbing event, “The whole…fiasco was a tragedy that could have been easily avoided.”

Thus armed with an assured historian’s voice, Jamieson places at the core of his book two main types of history. One is the Byzantine world of international diplomacy, which, at one point, he describes as a “nasty mess.” Primarily involving, first, the United States and later Norway, this is a world of astoundingly complex memos, speeches, letters, and announcements, almost all of them carefully toned or even evasive. The almost complete absence of overt sabre-rattling is remarkable. As the author writes at one point, “The Norwegian government would persist with their inquiries regarding the Sverdrup Islands, and in diplomatic fashion, the Canadian government would continue to politely fend them off or to ignore them altogether.”

The reference to the “Sverdrup Islands” here is particularly important for much of the latter part of the book. Astounding for many readers will be the fact that this group of large islands, directly north of mainland Canada, was the focus of intense land claims— from, oddly, far distant Norway. Why? As the author makes clear, during that historical period, territorial claims could be based on any one of three principles—first, the date of “discovery,” second the so-called “sector principle,” and, third—and crucial for a major part of the book the principle of “use and administration.” The fact that different principles were used at different points, often inconsistently, and driven by expedience, apparently added wonderful confusion and uncertainty. All of these, in turn, were complicated by the fact that, initially at least, even when Canada laid claim to land between various coordinates (thereby employing “the sector principle”) no one was very sure about what land actually existed there.

For many readers, no doubt, it was the increasingly important third principle—that Canada had to demonstrate to “the world” that “their” lands were being occupied and administered—that leads to the most arresting parts of the book. This is the second main type of history, far from the world of political manoeuvres. This is the world of hair-raisingly difficult conditions encountered by the small number of hardy souls who experienced enormous “isolation, hardship, cold and deprivation … in challenging environments.” Take the instance, where the weather was so cold that attempts to wash a floor even next to a roaring fire were impossible because the water kept freezing on the floor. Or the near disaster when, in the middle of a terrifying snow storm, the “shack” housing the men caught fire, forcing desperate attempts to salvage what could be saved and to find shelter in nearby outbuildings.

Jamieson knows both how to fascinate his readers and, simultaneously, to pay homage to the knowledge and skills necessary for survival. He makes vivid a life where conflicts over duties, injuries and boredom—especially during the darkest days—are intensified by lack of two-way communication with the outside world. Fascinatingly, messages, such as they were, came through transmissions, especially via a radio station in the U.S. To these general details he adds information that few readers are likely to have encountered—the facts, for example, that officers took to trapping Arctic fox (somewhat illegally) “to supplement their meagre wages,” or that, when not in uniform, “the men wore what the Inuit men wore, clothing made from caribou skins that had to be sewn by the [Inuit] women, the skins softened by them as well.”

The Inuit influence didn’t stop there. The officers struggle to learn how to handle dog teams and sleds, for example, and, important for their survival on missions from the detachments, to build igloos.

Igloos? Igloos, indeed. It is not just life on the detachments that Jamieson makes vivid, but life (and, indeed, near death) away from the detachments—all in the name of establishing a Canadian presence or “quiet penetration.” The author gives full reign to first person accounts of survival of, for example a short patrol where two teams were separated in a blizzard, one of them forced to spend the night under an overturned sled. And so on. An accidental harpoon wound, snow blindness, food poisoning, frostbite, dangerous encounters with walruses and bears— it seems what could go wrong did go wrong.

It is one particularly long patrol, though, that gives most resonance to the book’s title—a patrol involving Inspector Joy, Constable Taggart, and an Inuit, Nukappiannguaq. 1800 miles and 81 days, an epic trip away from supplies or communication, is the stuff of white-knuckle survival. Even the fact that the men had to hunt food for themselves and their dog teams added danger. As Taggart writes in his diary, “if our luck fails and we get no more bears we are going to be up against it.”

Of many recurring difficulties in all the patrols, arguably two stand out—those involving ice and dog teams. Far from being a swift glide over snow or ice, as Jamieson repeatedly shows, the ice was often a huge impediment:

Here repeated pressure from the sound had built up a wall of ice varying from twenty to one hundred feet high, all along the shore line. Huge cakes of ice had been forced over the wall and lay thick and loose in the narrow passage between the ice-wall and vertical cliffs forming the coastline, where we had to travel.

To get over the jagged ice walls in sleds that seem to be constantly breaking, cue—the dogs. A whole separate book waits to be written about the dog teams, given some of the details the author selects. At one point, for example, the hungry team devour a litter of newborn puppies. At another, a dog breaks its leg and needs to be shot. At another a dog dies from cold and exhaustion.

Wisely, though, the author saves the most telling subject matter—the Inuit—for near the end of his book. In one context, he documents some perhaps surprising awareness in the government of the need to respect Inuit wellbeing. At one point, for example, O.D. Skelton, Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs, warns:

Unless further steps are taken to protect the areas reserved as hunting and trapping preserves for the sole use of the aboriginal population of the North-West Territories, there is grave danger that these natives will be reduced to want and starvation through the wildlife being driven out of said preserves by the exploitation…by white traders and other white persons.

Repeatedly Jamieson selects incidents in which Inuit, women as well as men, are shown to be quietly and undramatically the backbone of the detachments and patrols. Nakappiannguag especially comes across in Jamieson’s treatment as the Tensing Norgay of the much-celebrated Longest Patrol. In his words, “Fortunately, the Inuit were close at hand at these remote detachments, for, given the worst-case scenario, they would know how to survive.”

It is only in the last part of the book, however, that more disturbing issues start to surface, what the author describes as “one of the darkest chapters in Inuit relationships with the Canadian government.” As he shows, a lot of apparently peaceful connections with the Inuit, whether involving relocation or physical work, were actually coercive. He even suggests (without being explicit) that coercion may have been involved in sexual relationships with Inuit women.

One of those relationships, though, whether coercive or consensual, becomes the basis of a final chapter, set initially in 2013. It says a good deal about Jamieson’s interest in the human element of the whole Arctic story that he dedicates a chapter to a web of ancestor-tracing that revealed, in the end, long-hidden relationships between descendants of an Inuit woman, Elisapee, and Corporal Taggart, one of the heroes of the “Longest Patrol.” This moving story of discovery seems an especially suitable endnote to this memorable and affecting book.

After all, while this history is from one perspective, about vast external forces—whether the natural phenomena of an often-savage Arctic, or national governments at loggerheads—most important for Jamieson, it seems, and most affecting for most readers, is the fact that the book is really about human nature, individuals exposed for their humanity by the very stuff of history and geography.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at UVic and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, UVic, and finally Lester Pearson College in Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at Banff School of Fine Arts and UVic. He lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here. [Editor’s note: Theo Dombrowski has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has reviewed books by Adrian Markle, Tim Bowling, Lisa Brideau, Brady Marks and Mark Timmings, Darrel J. McLeod, and Max Wyman for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster