Discovering oneself in Ireland

Lost Between the Stones and the Sea: A Journey of Discovery in Ireland

by Chris Brauer

New Denver: Maa Press (Dandelion Wine Publishing), 2023

$25.00 / 9781777349745

Reviewed by Ian Kennedy

*

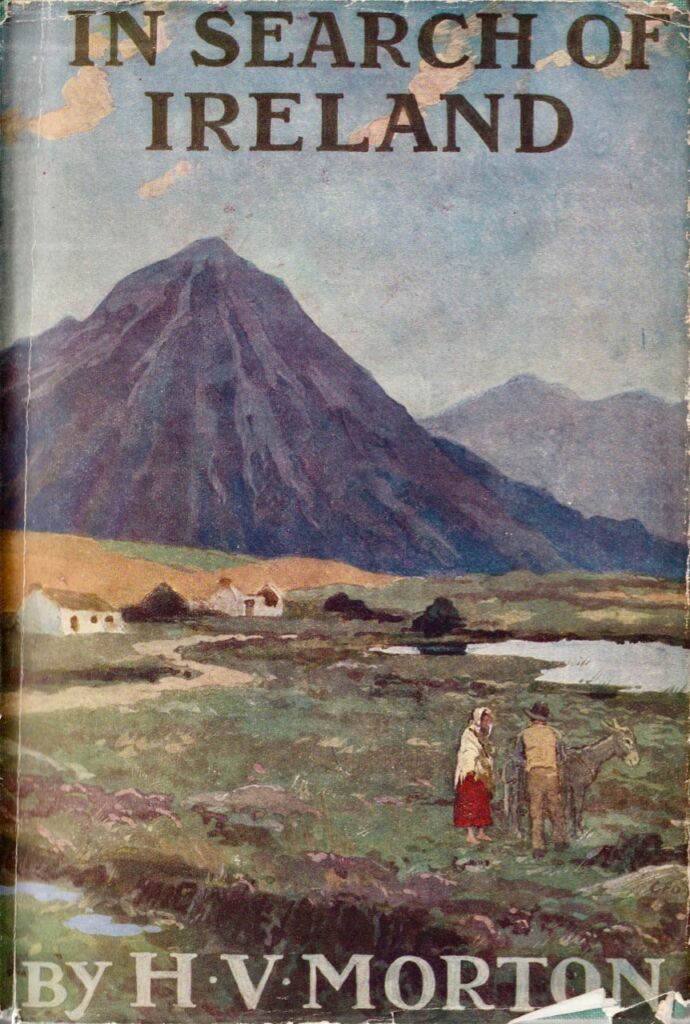

Many books have been written about Ireland including H.V. Morton’s classic In Search of Ireland (1930). Early in it he writes: “I was bound on perhaps the most stupid and thankless task which a man can set for himself: I was going to add another book to that mountain of books about Ireland.” Nearly a century later, in 2023, British Columbian Chris Brauer added Lost Between the Stones and the Sea to that immense, and ever-growing compendium.

Brauer visited Ireland, accompanied by his former wife Paula, some years ago, and more recently returned on his own in an attempt to “find himself.” He writes that he had a lonely life growing up finding it difficult to fit in. He tried head-banger music, Dungeons and Dragons, drama, fencing and the poems of Leonard Cohen in an attempt to adapt in his teenage years. Later as a teacher he claims to have been too busy teaching and preparing lessons to make friends with his colleagues. Eventually he traveled to Mexico, Malaysia, and Germany trying to find a place “where he belonged” and ended living for three years with his wife and two sons in Oman in the Arabian Gulf.

He returned to rural, eastern BC and, still unsettled in himself, he asked: “Where is my place? Where do I belong? Who are my people?” Eventually he decides to return, on his own, to Ireland, in order to discover himself in the Land of Saints and Scholars.

His visit primarily takes him to southern Ireland where he spends most of his time visiting Neolithic sites, such as Newgrange, and early Christian monasteries and churches, citing the history and relevance of each. He also visits the Cliffs of Moher, the Burren, the Dingle Peninsula, preferring to hike the hills and cliff edges, while staying in small villages and towns, avoiding Ireland’s cities such as Galway, Limerick, Cork, and Dublin.

Despite his fascination with ancient sites, Brauer also takes in live music sessions in pubs and indeed visits pubs frequently in his travels. He writes a whole chapter about them, an institution so much a part of Irish culture, and about Ireland’s favourite drink: “What a wonderful drink, Guinness is,” he enthuses. “A well-poured pint of the thick creamy stout is truly a thing of beauty. A pub is measured by how well they pour the ebony nectar, and shame to those who can’t master it. Brewed in Dublin since 1759, Guinness had over a ninety-percent market share in Ireland up to the mid-1970s. Ten million glasses are consumed worldwide every day.” Statistics worthy of note.

Seeking answers to his quest to better understand Ireland and himself, Brauer asks a barman, while sitting having a Guinness at the bar of a Dingle pub: “What makes this country so attractive to so many people?” “I’d have to say that its because nothing much happens around here with too much to worry about,” answers the barman. “Look around you, and you see life unfolding without anyone getting trampled – like they might in some big American city. And no one is in a rush, y’know. No one here is forgotten and, if anyone needs a helping hand, someone’ll come forward. We look after each other…”

These are interesting and insightful comments that reminded me of why I never liked David Lean’s 1970 movie Ryan’s Daughter, which Brauer mentions at length in his book. To my mind, Lean got it terribly wrong in his depiction of Michael, the village idiot, played by John Mills. In the film the people of the village treat him as an outcast, something, that to my mind, and as the barman says, would be unlikely to happen in a small community in Ireland, where people “look after each other” — just as the barman so presciently states.

Following his sojourns in Ireland, Brauer sat down to write his book, and tells of his unique writing routine. Every writer has his/her own writing mode, but his is quite extraordinary. “I go though all my writer’s rituals: burning incense, the smoke twirling and twisting in the sunbeams; lighting a beeswax candle, the flame flickering in a dark corner; placing an old recording of Gregorian chants on the turntable; stringing small woken beads around my neck and covering my head with a light hood; sitting down at my antique roll-top desk, with its stains and scratches and long drawers of forgotten treasures; and uncapping my fountain pen. It doesn’t take long before the world becomes unfocused and I have tapped into the creative flow.”

Brauer’s book often offers a mythical view of Ireland. He is happier among the sheep on his hikes of discovery of ‘standing stones’ – as the Irish refer to the Neolithic ruins that dot Ireland’s landscape, and talking to cats and being in his own company. Dublin receives short shrift and is dealt with in a trice: “…busloads of GORE-TEX-clad tourists buzzing with excitement as they queue up outside the Guinness Stonehouse…gaze at the Book of Kells, pound back pints in Temple Bar where most will purchase one of the following: a Guinness pint glass, a ‘Kiss me I’m Irish’ T-shirt, a turf candle, a tin of tea, a pair of Celtic cross earrings, a bar of whiskey chocolate, a penny whistle, a copy of Ulysses, a Claddagh ring, a Waterford crystal decanter, a worry stone, a snow globe, or any other item that would remind them of their time in and around (but not much further than the borders) of Dublin.” For Brauer: “My Ireland is more about sitting outside in the early morning fog… It is more about the stories of the stones and the flowers that grow in the spaces between. The unravelling of mysteries, but never fully succeeding in discovering the ultimate truth… It is more about looking out across the Blasket Sound and listening to the voices of dawn.”

In another passage he states: “I don’t feel out of place in Ireland. Don’t feel the need to escape. The need to force myself to do something out of character, I can wrap myself in a lovely Aran sweater and walk along the wild western shores on my own, or tuck myself into a dark corner and read poetry. Listen to tunes that most here at home would describe as ‘old-timey’ without feeling that I am the odd one out.”

In the end, Brauer arrives at the conclusion that Ireland is a place of ‘otherness’, and that “…ultimately what I found so captivating was the intense silence that permeates Ireland. It is not so much the absence of sound, but the presence of something that is not sound.”

Amap or two and the odd photographs would have helped the reader better understand what Brauer writes about and he could have done with fewer passages transcribed from the guidebooks that he constantly refers to. Nevertheless, readers learn a great deal about Irish history, Irish literature, and also some interesting tidbits about Irish lore. For instance: it turns out that the knit designs on Aran sweaters are not family-based patterns used to identify unfortunate Aran fishermen lost at sea and washed up on local beaches. This appears to be a myth begun by J.M. Synge in his 1904 play Riders to the Sea.

This is not a guidebook and will not be everyone’s pint of Guinness — but it might help some readers ‘discover themselves.’ For my part, I think I’ll search out a copy of Morton’s In Search of Ireland, a book my father used to have on his book shelf. I think I’ll find it more my ‘cup of tea.’

*

Born in County Donegal, Ireland, Ian J.M. Kennedy came to Canada in 1954 where he attended Burnaby North High School and earned a B.A. from UBC. Later he did post-graduate work at Queen’s University, Belfast, and on his return to Canada taught geography and history at Steveston Secondary School for thirty years. Following his retirement in 1999, he moved to Comox and became a rugby journalist, travelling the world and writing about a game he never played very well. Widely published in many magazines, his journalism also includes numerous articles about history, travel, motorcycling, cottage living, and pubs. His books include his recent The Best Loved Boat: The Princess Maquinna, Guide to the Neighbourhood Pubs of the Lower Mainland (Gordon Soules, 1982), The Pick of the Pubs of B.C. (Heritage House, 1986), Sunny Sandy Savary: A History of Savary Island 1792-1992 (Kennell, 1992), The Life and Times of Joe McPhee, Courtenay’s Founding Father (Kennell, 2010), and Tofino and Clayoquot Sound: A History (Harbour, 2014), co-authored with Margaret Horsfield. Editor’s note: Ian Kennedy has also reviewed books by Patrick Taylor, Jon Stott, Glen Mofford, Glen Cowley, and Peter McMullan for The British Columbia Review. Visit him at https://www.ianjmkennedy.ca/

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster