Far North, as it was

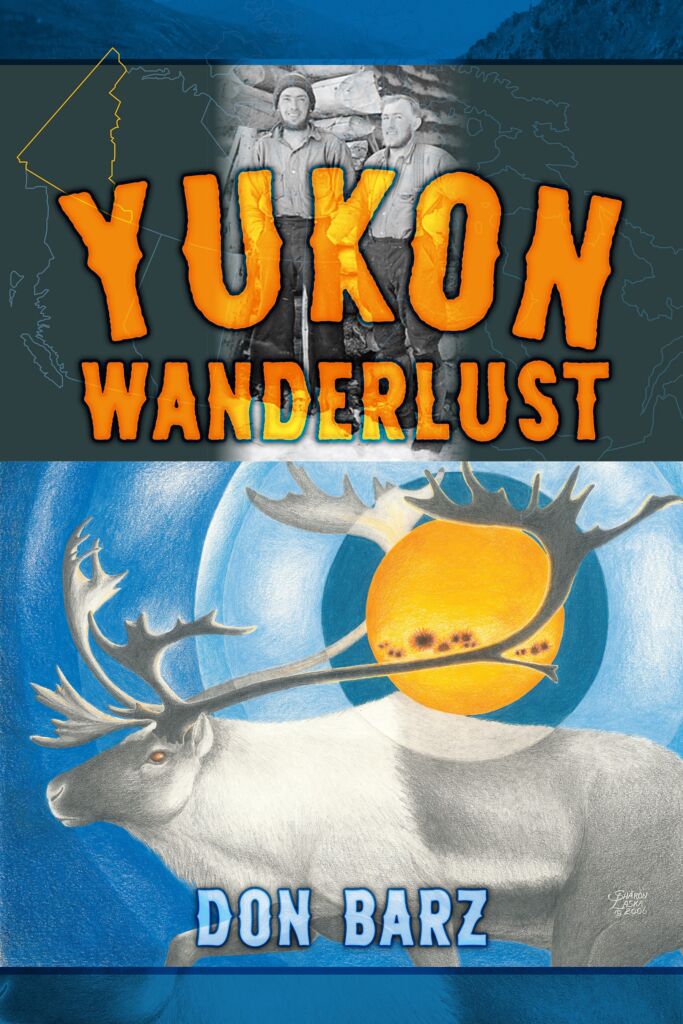

Yukon Wanderlust

by Don Barz

Clearwater: Celtic Frog Publishing, 2021

$29.95 / 9781989092415

Reviewed by Ken Coates and William R. Morrison

*

The North sustains a generations-old cottage industry in first person and secondhand accounts of life in the Arctic and sub-Arctic. This publishing phenomenon started with the early years of North American exploration and settlement, and has been sustained by the wide readership for journals of Arctic explorers, missionaries, and other adventurers who provided people from agricultural and urban settings with the vicarious thrill of experiencing northern winters and wilderness.

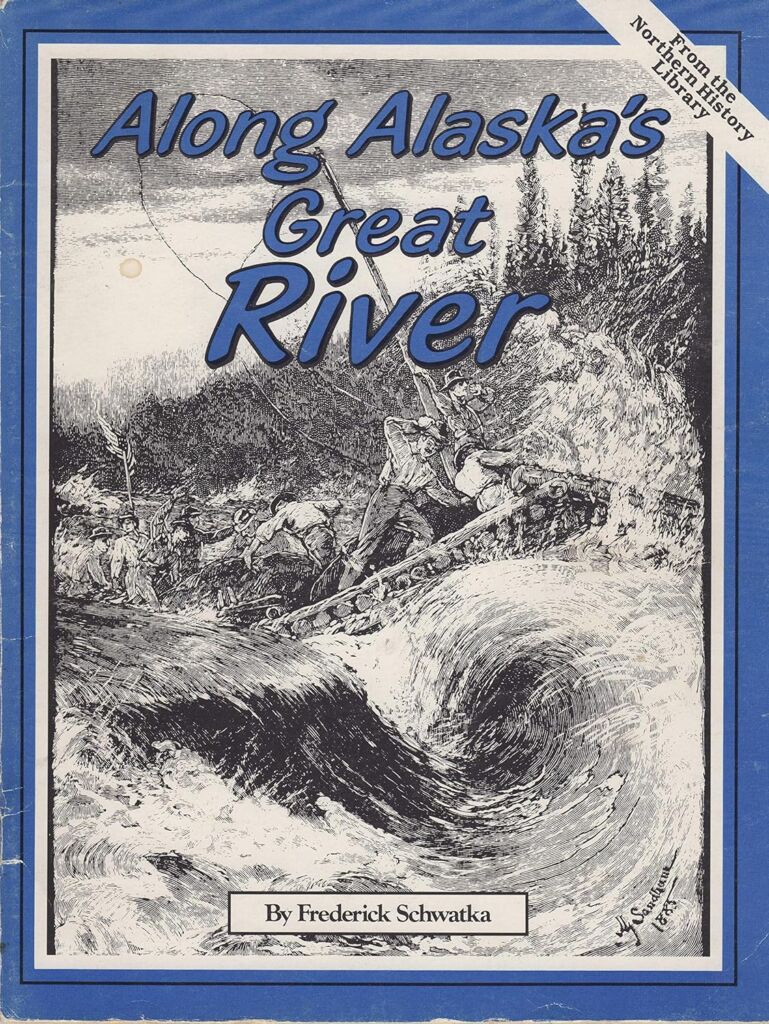

The Yukon has featured prominently in this northern literature. Even before the Klondike Gold Rush, diaries and memoirs of European travelers attracted wide readership. Explorers searching for the Northwest Passage produced a steady stream of bestsellers as did the writings of missionaries and scientists, like William Carpenter Bompas, Robert Kennicott and George Mercer Dawson. Even works by controversial observers like Frederick Schwatka’s Along Alaska’s Great River attracted attention.

The Klondike Gold Rush blew the top off the Arctic publishing enterprise. Hundreds of books, journal articles and newspaper accounts, including many written by people who never ventured North. Writers responded to the Klondike hysteria and flooded the market. The Northern bug, already strong, turned into a veritable literary virus following the 1896 discovery on Bonanza Creek. The Klondike seems to have produced as many quirky and interesting stories as it did gold nuggets, a fascination renewed in the 1950s with the publication of Pierre Berton’s Klondike that continues to the present.

While books on exploration, missionaries and the mining frontier remain the staples of northern publishing, consumer interest in the Arctic n Subarctic has been far from satiated. In recent years, an exciting and informative series of books have been written by Indigenous peoples, drawing on the knowledge of Indigenous elders or offering firsthand descriptions of communities, residential school experiences, northern politics, and Northern life generally. In northern bookstores – Max’s Fireweed Books in Whitehorse and The Yellowknife Book Cellar are superb regional booksellers—Arctic and sub-Arctic books have pride of place and attract wide readership. Northern literature is alive and well.

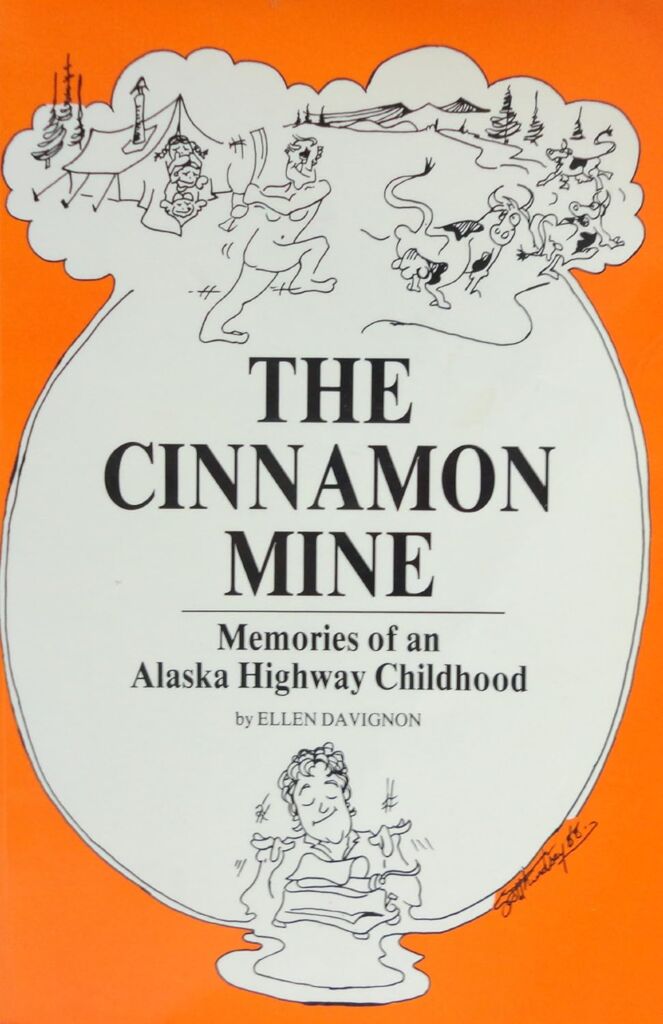

Major gaps remain of course. The have been some fascinating books on women’s lives, like Ellen Davignon’s The Cinnamon Mine, an insightful portrait of highway camp life along the Alaska Highway. But much more remains to be written. A small number of northern politicians, like Stephen Kakfwi in Stoneface: A Defiant Dene, produced memoirs of their private and public lives. In the contemporary period, the most glaring omissions include the remarkable men and women whose work as social reformers, community-level leaders, elders and Indigenous knowledge keepers, and land claims negotiators created the modern North. Meanwhile, outsider adventurers in large numbers continue to produce a steady barrage of personal accounts of kayaking, walking, sailing, painting, drawing, photographing, or otherwise encountering northern lands. The spirit of the Explorers’ Club lives on!

Chronologically, the largest gap in writing on the North, and the Yukon specifically, relates to the interwar years. The Yukon declined quickly as the Gold Rush petered out and suffered substantial outmigration during the First World War. Some 27,000 people lived in the Yukon in 1901, falling to under 4200 by 1921. The number of residents grew to around 4,900 just before the construction of the Alaska Highway in 1942, less than 20% of the size of the territory’s population at the turn of the century. That the territory grew at all was due to private reinvestment in the Klondike area dredge mining operations and the intermittent development of mineral deposits near Mayo in the central Yukon.

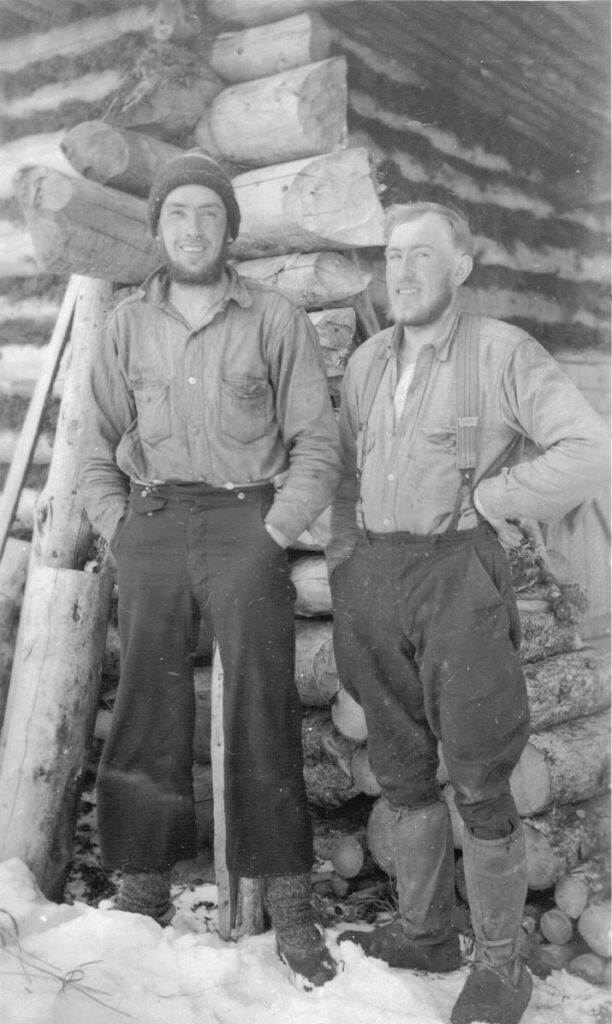

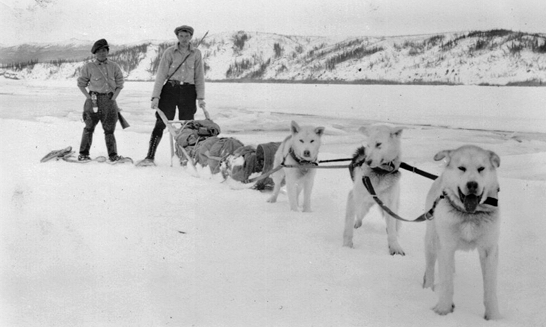

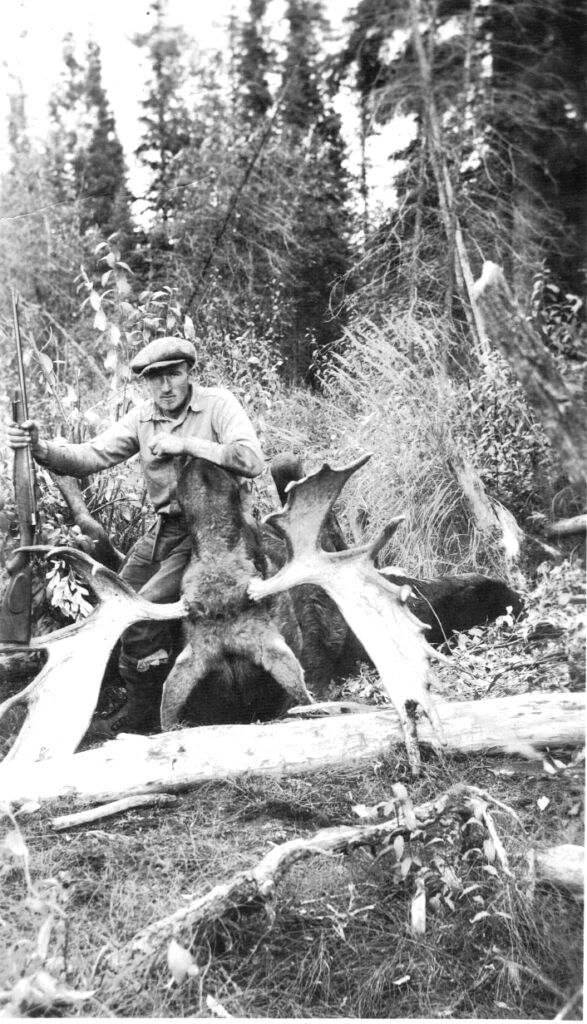

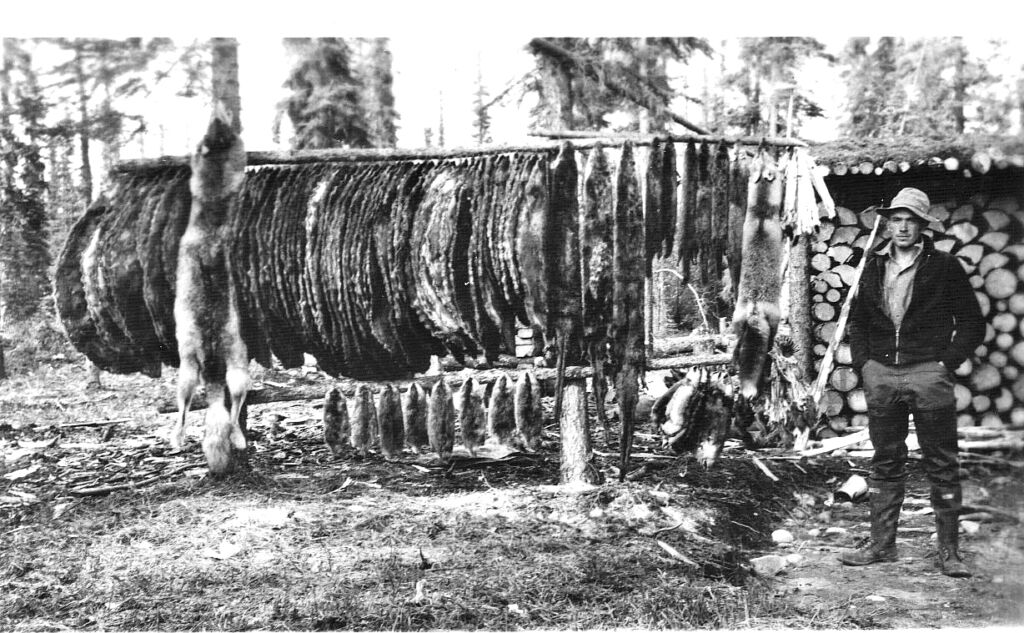

Yukon Wanderlust is a unique and fascinating addition to the northern literature. Brothers Art and Ernie Barz were pragmatic, hard-working men, driven North in 1937 by the Great Depression and reports of high wage employment in the Klondike dredge mining operations in the Yukon. Quickly tiring of work for the mining companies, they started as unofficial fur trappers and later set up a trading post in the Bonnet Plume and Peel River region. They stayed until 1942, when they left their traplines, supplies and cabins and headed south through Aklavik and Norman Wells. The walked into the maw of the United States Army engaged in the construction of the Alaska Highway and the CANOL Pipeline. Project managers were desperate for workers with direct experience in the Far North and offered them top wages to work on the project. The Barz brothers had had enough of the North and had money in their pockets from their time as trappers and traders to start life anew in the South. They relocated to southern British Columbia, although they returned to the Yukon temporarily for an unproductive prospecting trip in their former trapping area.

Don Barz, son of Ernie Barz, did an excellent job of recording a series of remarkably self-effacing interviews with his father and Uncle, Art. While he included long excerpts from the interviews, he did substantial archival and other research to check his relatives’ memories and to add context and background to their observations. The author capitalizes on a substantial cache of family historical photographs, supplemented by other images, to provide visual documentation of trapping and trading experiences in the Yukon.

The result of Don Barz’s work is an insightful and highly personal portrait of life in the Yukon between 1937 and 1942, focusing on the mining experiences, fur trapping, fur trading, and travel of the Barz brothers. He introduces the people that the two men worked with, met and befriended. The brothers described, in kind and friendly terms, many of the First Nations trappers and hunters they encountered. He outlined, in highly informative ways, the reciprocity and mutual support that dominated life in the rural Yukon. Their accounts of winter life are, in a word, chilling, offered in the matter-of-fact and practical terms that one quickly comes to expect from the Barz brothers and their chronicler.

The book stands apart in the first-person literature in the relative absence of the self-promotion that is so common in northern newcomer writer and the author’s substantiation of the movements, personalities, and events described in the book. Far too many non-Indigenous books on the North are presented in the “front lines of history” format, with the authors determined to emphasize their path-breaking work, travels, observations, or experiences. Yukon Wanderlust has none of that self-aggrandizement. Their northern activities are described in a matter-of-fact and unexaggerated fashion. Much commentary is reserved for the basics of life: building shelters, harvesting food, surviving extreme cold, and the practical aspects of life in the North. There is none of the romanticization of the North made popular by Vilhjalmur Stefansson in such books as The Northward Course of Empire and The Friendly Arctic. Both brothers agreed that their time in the Yukon was interesting but neither wanted to do it again. They retained strong memories of northern cold and vulnerability to the end of their lives.

Yukon Wanderlust seemingly started out, as such personal books do, as a family tale, designed as much for grandchildren, but it is much more than that. The pre-war period in the Yukon remains little known and this book makes a valuable addition to the literature. It is most effective for its portrait of Yukon life away from the mines and outside the Dawson City to Whitehorse corridor. The book is also a reminder of the important and typically friendly relations between fur trader and First Nations people and the support and encourage provided to each other in the rural areas.

The Barz brothers made no effort to carve out a place for themselves in Yukon lore. They avoided adding their names to Yukon places for the eminently practical reason that North Americans in the late 1930s and thereafter were not well disposed to German names. They and Don Barz do not make more of their lives than they should, but together they provide an unusually insightful description of Yukon life before the Northwest Defense Projects transformed the region. Yukon Wanderlust will interest Yukoners keen to learn more about the pre-Second World War years and historians interested in the 20th century fur trade and rural life. There is a great deal here for the armchair, vicarious traveler, particularly those interested in a frank, unromantic but compelling description of life in the northern fur trade.

This is not a work of soaring or poetic writing, and therein lies its authenticity. The Barz family will not be mistaken for Jack London, Robert Service, or even Stefansson. But this is not a limitation at all. These are frank, even perfunctory commentary on northern realities. The blunt descriptions of coping with extreme cold, long winter travels, months of social isolation, and the economic uncertainties of northern fur trading are much preferable to the self-aggrandizing tracts that are so common in northern literature. Art and Ernie Barz were obviously practical people, working hard to make a living and making no effort to make themselves famous. Don Barz maintains that approach, focusing on placing the lives of his father and uncle in historical context and being faithful to their life story. Readers will learn a great deal about Yukon life in this nicely assembled, well-illustrated and matter-of-fact biographical account of two ordinary, but nonetheless remarkable, northern lives.

*

Ken Coates and William R. Morrison are the authors of Land of the Midnight Sun: A History of the Yukon and numerous other works on northern Canadian history. William has retired from the University of Northern British Columbia and now lives in Ladysmith, B.C. Ken is a Professor of Indigenous Governance at Yukon University.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction, poetry), Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster