Knowing the country: the unfilmed Ethel Wilson

Knowing the Country: The Unfilmed Ethel Wilson

An essay by Dennis J. Duffy

[Editor’s note: this is an essay in a series on the subject of the relationship of British Columbia literature and film begun with Ron Verzuh’s essay When Hollywood Calls]

*

How strange the lonely fence on that wild hillside. It had been white once, and so had the three small wooden crosses within the picket fence. The rolling rippling hillocks at the roadside rose and obliterated the more distant crosses up the hill and the neat humble picket fence that gave the crosses their privacy and the look of respect and care. Men lying in their own bit of soil in that immensity. Maggie quickly saw and as quickly lost sight of the crosses. She turned to the man beside her.

“Do you know this country?” she asked, hesitant.

–Ethel Wilson, Swamp Angel (1954)1

I like to think I know that country. I’ve often noticed those forlorn graveyards along roads in the BC Interior, and wondered about them. Glimpsed from a passing vehicle, like a travelling shot in a road movie or a government travelogue, they still retain their poignant mystery.

The intermittent chronicle of British Columbia filmmaking offers many examples of motion pictures that could have been made, but somehow never were. When we factor in the source stories provided by BC writers, the amount of untapped potential is painfully apparent. The province’s history and literature abound with stories that would lend themselves to the cinematic eye. Perhaps no BC writer represents this potential as dramatically as Ethel Wilson (1888-1980). The modest size of her published oeuvre—six slim books, comprising four novels, two novellas, and a short story collection—belies the rich variety, unique vision, and enduring interest found in that work.

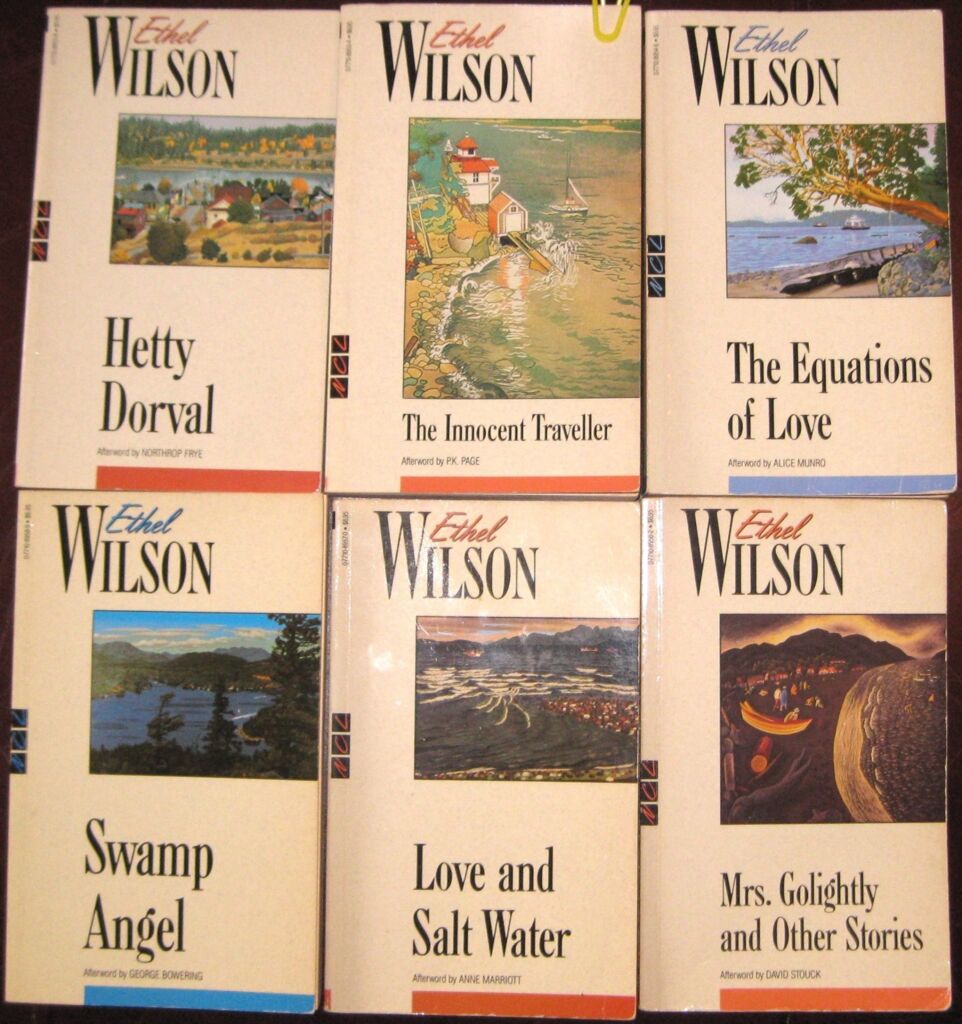

As George Bowering tells us, Wilson “genuinely loved the physicality of British Columbia, and used her great sentences to make it brightly visible.”2 McClelland & Stewart’s 1990 uniform edition of Wilson’s work in the New Canadian Library series fittingly reflected this idea. The cover of each paperback featured a BC landscape by painter E. J. Hughes. Wilson excelled in embroidering intimate human stories and placing them in the variegated landscape of her adopted province. In my view, her stories are profoundly cinematic and almost demand to be filmed.

In Hetty Dorval (1947), the intricate dance between the monstrously self-absorbed title character and her mesmerized observer, young Frankie Burnaby, begins near the town of Lytton and the river benches at the confluence of the Thompson and the Fraser. In “Lilly’s Story” (the second half of The Equations of Love, 1952), Lilly Waller’s search for respectability and safety takes her from Vancouver’s Chinatown to an idyllic rural life in Comox, to a Fraser Valley cottage hospital, and finally to an anonymous job as a hotel maid in Toronto. In the quiet tour-de-force that is Swamp Angel (1954), Maggie Lloyd runs away from her miserable marriage and into the heart of the Interior. Her first refuge is a cabin on the Similkameen River, where she fishes and meditates. After a few days, she takes an eye-opening bus trip up the Fraser Canyon highway (excerpt above), and finally finds a community of sorts at a remote fishing lodge in the mountains above Kamloops. Wilson calls the lodge location “Three Loon Lake,” but a well-travelled British Columbian will recognize it as Lac Le Jeune.

A recurring motif in Wilson’s fiction is a female protagonist trying to physically and mentally distance herself from an untenable situation—an act that Michael Ondaatje called “landscape suicide.”3 Hetty, Lilly, and Maggie all pursue this option—as does Ellen Cuppy, the heroine of Love and Salt Water (1956). Ending her engagement to a bitter and misanthropic First World War veteran, Ellen leaves Vancouver (and the Pacific shores she loves) to take shelter in Saskatoon.

Some of Wilson’s short stories took her into less familiar or more hostile landscapes, like the ominous Egyptian desert in “Haply the Soul of My Grandmother.” Or, most memorably, the downright surrealistic environs of Cut Off, the eerie prairie railroad station in her last published story, the remarkable “A Visit to the Frontier” (1964).4

At almost every turn in Wilson’s work, we are presented with human conflict contained in a vivid natural setting. In her best work, the landscape is another character, and an eloquent one. To a BC resident, or (I suspect) to any discerning reader, the selected landscapes offer much more than “ten cents’ worth of view.”5 Even the characters are aware of the importance of their settings. In Hetty Dorval, the author makes Frankie Burnaby insightful beyond her years, and has her hold forth about “the genius of place” and its significance in her Lytton childhood.6 Topaz Edgeworth, the eccentric maiden aunt at the centre of The Innocent Traveller (1949), seems to vibrate like a tuning fork with her love of landscape. Arriving in Vancouver after a long migratory journey from Hertfordshire, she is thrilled by her new home. “British Columbia stretched before her, exciting her with its mountains, its forests, the Pacific Ocean, the new little frontier town, and all the new people.” Elated, Topaz draws “long breaths of the opulent air” and dances with joy.7

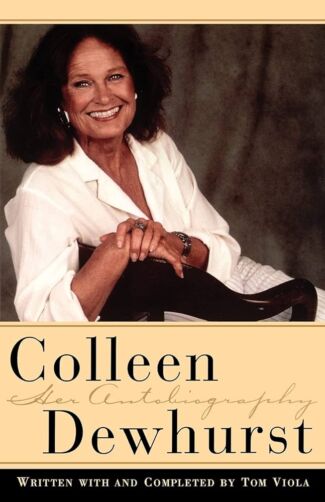

Why in God’s name didn’t somebody film these stories?, I find myself asking. People did try. Philip Keatley, the Vancouver film producer who brought Cariboo Country and The Beachcombers to CBC Television (and later Cold Squad to CTV), couldn’t pry the novels out of Wilson’s grasp.8 Starting in 1953, literary agent Ruth May went to considerable effort to sell “Lilly’s Story” to the movies. Broadway playwright John Patrick bought an option on the film rights and actually wrote the screenplay, but it was never produced.9 Toronto actress Frances Flanagan campaigned just as enthusiastically for a film of Swamp Angel, but the project never got off the ground. Actress Colleen Dewhurst, a memorable force of nature in many films and plays, was proposed for the role of Maggie Lloyd’s friend, the retired circus pistol-juggler Nell Severance.10 I suspect Dewhurst would have been perfect.

Ultimately, only two of Wilson’s stories have made it to film. In the 1970s, Vancouver filmmaker Peg Campbell made a charming student film from the vignette “I Just Love Dogs.” In 1991, Stephen McCallum made an animated adaptation of the tragic short story “From Flores” for the National Film Board. Both stories are from Wilson’s last book, Mrs. Golightly and Other Stories (1961).

There are also Ethel Wilson homages in other formats. Theresa Kishkan’s novella The Weight of the Heart traces a literature student’s road trip along Highways 1 and 97, re-tracing the path of her own family tragedy.11 Kishkan evokes the story-trails of both Wilson and Sheila Watson (The Double Hook).

I imagine that the fantasy casting of unfilmed books is not uncommon. I’ve certainly done it. In the 1990s, I was impressed and moved by Emma Thompson’s performances in two Merchant-Ivory adaptations: Howard’s End and The Remains of the Day, adapted respectively from novels by E. M. Forster and Kazuo Ishiguro. She won the Best Actress Oscar for Howard’s End. After she won her second Oscar (for Best Adapted Screenplay, Sense and Sensibility, 1995), I began to fantasize about sending Ms. Thompson a copy of Swamp Angel, suggesting she write the screenplay and play Maggie Lloyd. Hell, I would have chartered a floatplane and sent her to Lac Le Jeune on my own dime.

July would be the ideal time. Long before I encountered Swamp Angel, my family camped out at Lac Le Jeune Provincial Park on a May long weekend. It was a beautiful place, I remember, but we were sleeping in a tent trailer at 4,200 feet. We all wore long johns under our pyjamas, and when we got up for breakfast, we found that our washing-up water had frozen. As Wilson reminds us, life “is a difficult country, and our home.”12

- Ethel Wilson, Swamp Angel, New Canadian Library (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990), 71. ↩︎

- George Bowering, “Afterword,” in Wilson, Swamp Angel, 214. ↩︎

- Michael Ondaatje, Coming Through Slaughter (Toronto: General Publishing, 1976), 22. ↩︎

- Ethel Wilson, “A Visit to the Frontier,” in 4Ethel Wilson: Stories, Essays, and Letters, ed. David Stouck (UBC Press, 1987), 45-55. ↩︎

- Ethel Wilson, “A Drink with Adolphus,” in Mrs. Golightly and Other Stories, New Canadian Library (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990), 73. ↩︎

- Ethel Wilson, Hetty Dorval, New Canadian Library (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990), 65-66. ↩︎

- Ethel Wilson, The Innocent Traveller, New Canadian Library (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990), 108. ↩︎

- Keatley discussed this in a 1980s (?) audio interview or magazine article that I remember clearly, but can’t exhume at this remove. ↩︎

- David Stouck, Ethel Wilson: A Critical Biography (University of Toronto Press, 2003), 159-60. John Patrick (1905-1995) was best-known for adapting the novel The Teahouse of the August Moon for stage and screen. ↩︎

- Stouck, 205-6. ↩︎

- The Weight of the Heart (Windsor, ON: Palimpsest Press, 2020.) ↩︎

- Edwin Muir, “The Difficult Land,” cited in the epigram of Mrs. Golightly and Other Stories. ↩︎

*

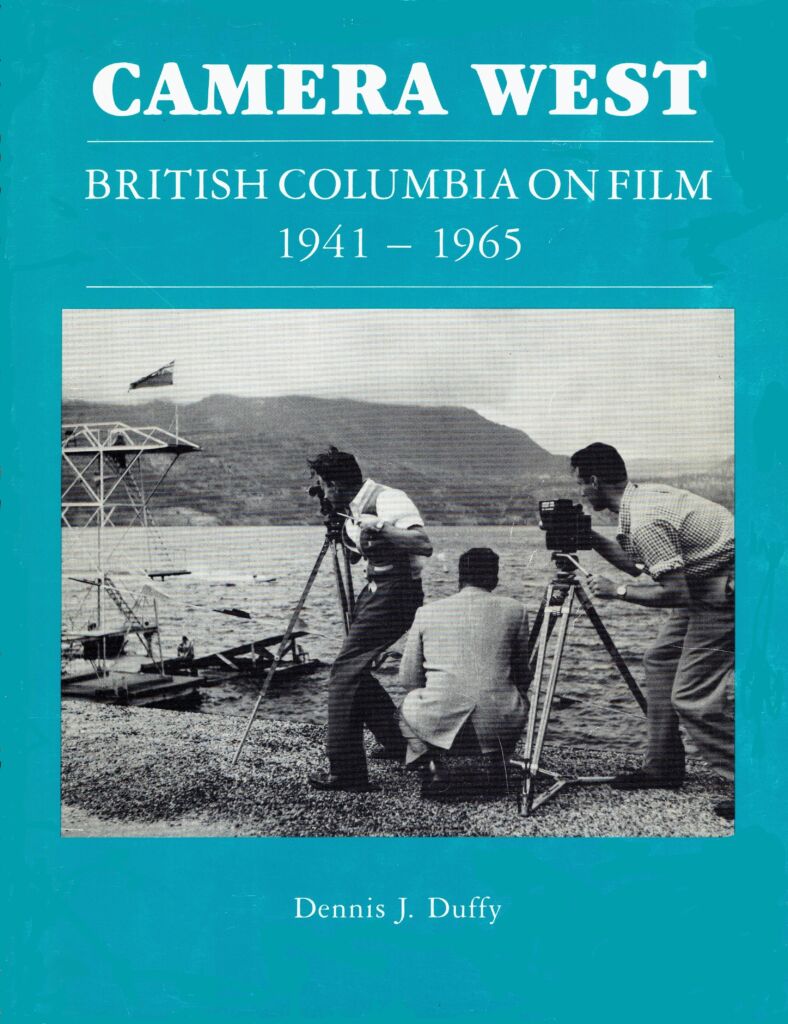

Dennis J. Duffy is the author of Camera West: British Columbia on Film, 1941-1965. (BC Archives, 1986) and the producer of the DVD Evergreen Playland: A Road Trip through British Columbia (Royal BC Museum, 2008). He retired from the Royal BC Museum in 2017, after a long association with the BC Archives’ audio-visual collections. He writes about BC film history on his blog, Seriously Moving Images [https://movingimagesweb.wordpress.com/].

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “Knowing the country: the unfilmed Ethel Wilson”

2.5 months after publishing the above essay, I’ve just now spotted an embarrassing error. Emma Thompson won her Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for the script of SENSE AND SENSIBILITY, not for PRIDE AND PREJUDICE! I’m chagrined that nobody called me on that. MY BAD!

Not to worry, Dennis. Done and dusted, so to speak. Sense and Sensibility (1995). A powerhouse cast: Thompson, Winslet, Grant, Rickman. It must have been quite a daunting task to adapt Austen into a screenplay. Also added to this post is a fresh cover image of Camera West. Thanks Dennis!

A moving and very knowledgeable tribute to Ethel Wilson’s writings. Thank you for remembering her and reminding us of her importance.

Thanks, David!