When Hollywood calls – an essay

When Hollywood Calls

An Essay on How Books Get Made Into Movies in BC

By Ron Verzuh

[Editor’s Note: This is the first in a possible series of essays on the process of transforming BC books into movies. It is intended as a starting point to encourage other BC Review writers who want to submit their views and experiences on the relationship of BC literature and film.]

*

You are a British Columbia novelist whose first big book has just been published to positive reviews. Will Hollywood call to solicit your collaboration in converting your work to the magical flicker of the cinema? If so, what will you reply?

When New Yorker writer David Grann learned that film director Martin Scorsese wanted to adapt his book, Killers of the Flower Moon, into a movie, he was “nervous.” Arguably he is the greatest living Hollywood director, but would Scorsese, the maker of several fictional films about the mafia, accurately adapt Grann’s story?

If the same call came to Pete McCormack, a Vancouver novelist, musician, and documentary filmmaker, he said he might have swallowed and asked if the caller had the right number. He was joking, of course, and would have been as excited as Grann. He might have been even more excited if it were Stephen Spielberg, the maker of Jaws (1975), ET (1982), and Jurassic Park (1983) among so many others.

Spielberg did make the call in 2016 when he filmed The BFG, a Roald Dahl fantasy about an orphan girl who befriends a benevolent giant, entirely in Vancouver. “He raves about working in Canada,” wrote Kim Izzo in the everythingzoomer.com newsletter.

So, there may still be hope for McCormack, but he’s not waiting by his cellphone. However, for him and many of BC’s growing population of successful writers, such a surprise call is entirely possible. Maybe not Scorsese or Spielberg, but other great directors have chosen BC as a prime film-shooting location. Indeed, Vancouver is sometimes called Hollywood North and it is proving that it has the filmmaking infrastructure to produce major motion pictures.

In another era, world-famous BC writer Malcolm Lowry, sitting in his Deep Cove shack in North Vancouver with a glass of his favourite tipple at hand, might have heard from Hollywood. That didn’t happen in his lifetime; he died in 1957. But in 1984, John Huston, the maker of such notables as The Maltese Falcon (1941), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), and The African Queen (1951), took it on.

In his prime, Huston was at least as famous as Scorsese. A member of Hollywood royalty, he optioned Lowry’s Under the Volcano and in 1984 it was released. Unfortunately, BC missed out as a location because Huston set his film in Mexico at the time of the Spanish Civil War. Although Lowry was a British-born BC author, the province did not get any credit for the film version of a drunken ex-diplomat’s fall from grace.

Grann was especially nervous when Scorsese called because his story was about “one of the more monstrous crimes and racial injustices in American history.” He was referring to the murderous theft of Osage First Nation oil wealth in Oklahoma just after the First World War. He was not disappointed.

Like Grann, McCormack would have been honoured to get the call. He has made several documentary films, like Facing Ali, the 2009 tribute to the champ, and Uganda Rising (2006), about the children who escaped the Lord’s Resistance Army in post-Idi Amin Uganda. But so far Hollywood film studios have only optioned his scripts. No doubt he shares Grann’s concern that the history not be Hollywoodized.

“The thing that really struck me was less the parallels with Scorsese’s previous work,” Grann said, “but his commitment to this history, and to getting it right.” McCormack describes this moment as a “dance” to the creative music of both writer and director.

There are plenty of stories in BC’s history that somewhat parallel the Osage crimes against indigenous people and several films that were inspired by creative writers. Filmmakers seeking tax breaks, fabulous scenery and a talent pool of writers, are always seeking the quintessential BC story.

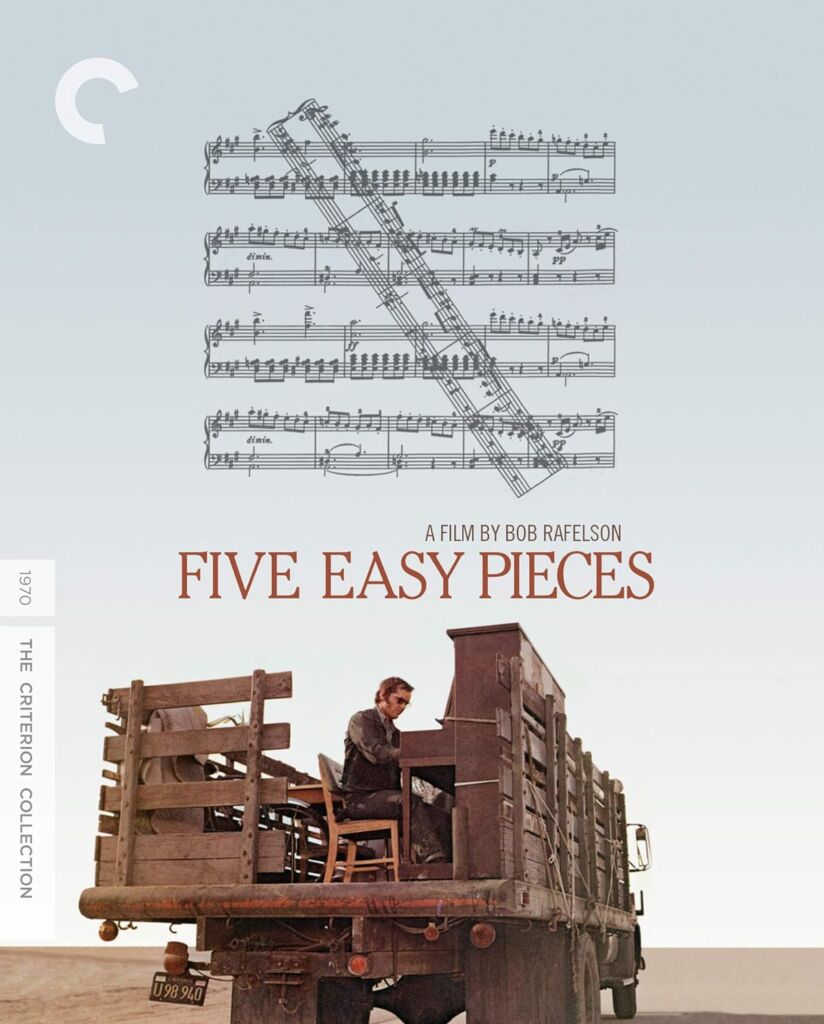

Remember the 1970 film Five Easy Pieces with Jack Nicholson playing a washed-up classical pianist? Director Bob Rafelson, also the inventor of the faux-rock group The Monkees, shot some of it on Vancouver Island back in 1970. Regrettably, the memorable diner scene, where Nicholson clears the table, was shot in a Denny’s outside Portland, Oregon, not in BC.

A big motivation for a director’s call is the location. We live in a place that has it all. For McCormack this is critically important. “If you have a really good director and a good setting you can really capture so much with setting and location,” he says. His own early novel Understanding Ken, about a 10-year-old hockey player set in his home area in the West Kootenays, has not been made into a movie. If that were to happen, McCormack would want the setting to evoke the cold climate of the partly autobiographical story.

Robert Altman does that effectively in the 1971 film McCabe & Mrs. Miller by shooting it in the skiing town of Squamish, BC. It’s one of the earliest big films to be shot in the province and the setting contributes much to the sometimes bawdy tale of a gunslinger-gambler who teams up with a brothel madam.

The film is not based on a book by a BC author. That honour goes to British novelist Edmund Naughton whose 128-page 1959 novel suited Altman, although it seems doubtful that Naughton ever set foot in the Pacific Northwest. Interestingly, though, the director counted on a lot of BC talent. For example, Vancouver actor Jackie Crossland played one of the sexworkers in Julie Christie’s brothel. There were also tie-ins with the literary community.

Writers, directors and producers who saw the film were no doubt attracted to it as a western with a distinctive look. That look can be credited to the local set construction crew and shaped the fictional town. It caught people’s attention in Hollywood and helped pave the way for other films to be shot here.

Films such as Snow Falling on Cedars (1999) rely heavily on setting. Based on the David Guterson novel, and set in the San Juan Islands in the 1950s, this “classic whodunnit” needed wide open picturesque west coast scenery to contrast with the claustrophobia of what becomes a courtroom drama. Scenes were shot in Greenwood and New Denver.

McCormack views setting as a critically important factor in other shot-in-BC films. Rambo, for example, was filmed around Hope, BC, in 1982 with Toronto’s Ted Kotcheff directing. Despite the Americanization of the film, McCormack says, “You can feel that backroads feel. You feel the Pacific Northwest.”

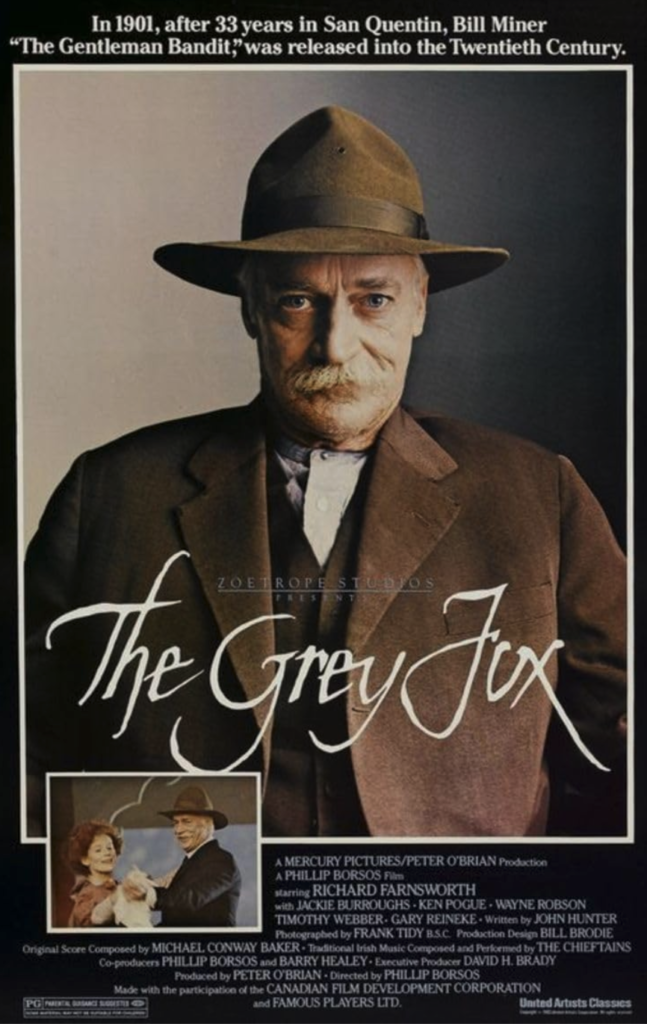

The same year, Canadian director Philip Borsos made The Grey Fox, about the notorious train robber Bill Miner using a screenplay by Vancouver writer John Hunter. Miner lived in Kamloops, BC, where the film has him falling in love with photographer Katherine Flynn. The fictional Flynn is played by the late Vancouver actor Jackie Burroughs. The filmmakers might have intended Flynn to represent Ontario-born photographer Mary Spencer who did photograph the train robber on his arrest in Kamloops in 1906. Apparently the photos caused a sensation when they appeared in the Vancouver Daily Province. The film was partly shot around Pemberton and Lillooet, BC, and was the only film allowed to shoot at historic Fort Steele in the East Kootenay.

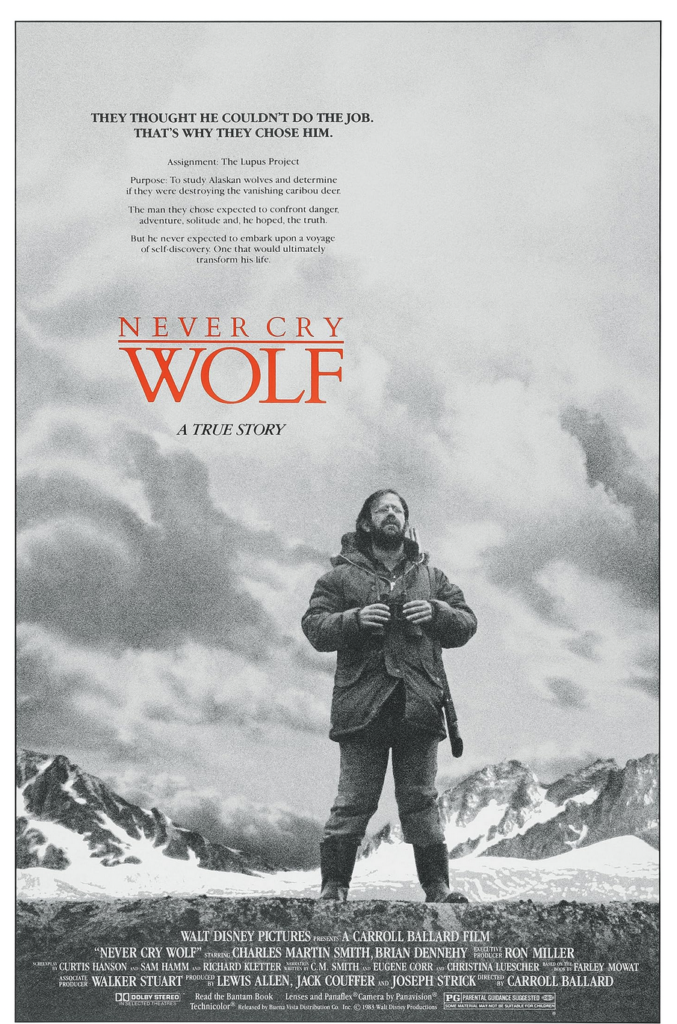

The following year, Never Cry Wolf, Canadian author Farley Mowat’s intimate story of living with wolves, was shot in Atlin, BC, under the guidance of Los Angeles director Carroll Ballard. The critics gave it high marks for depicting the Inuit people fairly on screen. Again the writer’s concern with accuracy is paramount.

Squamish got another shot at Hollywood fame when Robin Williams and Al Pacino showed up in Insomnia in 2002, about the murder of a teenage girl in Alaska. The story was borrowed from an Norwegian film, so once again the province starred but BC film talent did not.

Other BC writers are now come-from-aways or more correctly gone-aways. For example, Patrick deWitt, who was born in Sidney, BC, scored big with his 2011 novel The Sisters Brothers. It won a Governor Generals Award and was later brought to the screen in 2018. French director Jacques Audiard shot in Spain, although the action occurs in California in settings that could easily have been BC. The novelist now calls Portland, Oregon, home.

Of course, location and setting are only part of the equation. Also critical to the process are casting, narration and capturing the “inner voice” of a character. McCormack describes the process as “making the magic happen.” To do it, he paraphrases Hollywood director Sidney Lumet: you need a good cast, a good script, a good director, a good director of photography, a great editor, “but in the end you also need luck.”

BC doesn’t have any more luck than other locations, but it has the other ingredients in spades. Take casting. There’s plenty or acting talent in our midst. Vancouver’s Ryan Reynolds has starred in several films. Comedian and talk show host Seth Rogen also hails from Vancouver as does Beverley Hills 90210 star Jason Priestley. Pamela Anderson of Baywatch fame was born in Ladysmith, BC. Deadwood alumna Polly Parker comes from Pitt Meadows, BC, and Taylor Kitsch is John Carter in the 2012 sci-fi thriller.

There is a list of BC’s 30 top actors here: https://www.bcmag.ca/30-famous-actors-from-british-columbia/. And let’s not stop at the stars. Hollywood North Extras in Burnaby books performers for those little appearances that add a dab of essential realism to any film. Friends of mine have scored non-talking parts in several Vancouver-made films.

If McCormack does get the call from a Hollywood director one day, and he could since he’s met several including Oliver Stone, and interviewed plenty of Hollywood people, that would put him “inside the machine.” It’s a status that gives “your life a new credibility.” Again, BC has the directing talent. Neill Blomkamp topped the list with District 9 (2009), a different take on South African apartheid, Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen directed The Interview (2014), a CIA thriller-comedy, and Sturla Gunnarsson who has directed well-liked television shows like DaVinci’s Inquest and more recently Schitt’s Creek.

Again, the list is extensive. Allan King, one of our great documentary filmmakers, was also born in Vancouver. He died in 2009 but not before leaving superb works like Warrendale (1967), about emotionally disturbed children living in a Toronto institution, and A Married Couple (1969), an inside look of a marriage that broke some cultural ground.

So, we’ve got location, set design, casting and directing aced. Of course, however thrilling it would be to get your work tagged for Hollywood film treatment, there is no guarantee that what you wrote will come out that way on the screen. The master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, famously confided that when he chose a book for a film he went straight to the nub or heart of the story and plucks it away from all the rest.

McCormack agrees. The key is to find the core story. When Hitchcock saw what the book was about he got rid of the things it was not about. “You really do have to find out what the essence of the story is and capture that essence.” At that point, your choice as a writer is limited. Do you say “no” to a famous director out of fear that you’ll lose control? Or do you take your chances and hope for a true transfer to the screen?

That brings us to the talent pool for BC screenwriters. McCormack does his own writing, but plenty of other BC writers are available to adapt novels and short stories, the latter being a great source of filmable material. Chris Haddock is among the most skilled and his efforts made DaVinci’s Inquest and Intelligence shine. Many others are for hire at https://www.upwork.com/hire/screenwriters/ca/vancouver-bc/.

In the Oscar-nominated film American Fiction, a Black novelist gets the director’s call. He’s a frustrated writer whose quality books are not selling. His agent is unhappy. He wants something grittier, closer to the real Black experience. Here we have McCormack’s inner voice at work.

The writer decides to write a trashy book to show that it isn’t worth publishing. Au contraire says a publisher, dangling a fat advance cheque in front of the writer. The whole gambit unravels when the writer has to come clean and admit he’s used a penname on the book. Then Hollywood steps in with a young director optioning the story, then twisting the truth and the untruth to fit his needs.

American Fiction illustrates what can happen when a serious novelist gets a call from Hollywood and is cornered by McCormack’s “machine.” You have some control over what you’ve written, but you can get lost in the process. The movie is listed under Best Picture at the 2024 Oscars scheduled for March 10. I suspect McCormack will cast his vote for it. I might do the same, but the competition is as stiff as ever in Hollywood.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian, and documentary filmmaker who writes regularly for BC Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

11 comments on “When Hollywood calls – an essay”

PS: Oh, I forgot–Lowry is not listed in the “Volcano” credits as co-screenwriter, but solely as the author of the source novel. Guy Gallo wrote the screenplay.

Malcolm Lowry died in 1957, twenty-six years before Huston’s film was made. I seriously doubt whether his Deep Cove (Dollarton) shack had a telephone–it didn’t even have electricity. The character of Katherine Flynn in “The Grey Fox” was fictional, perhaps _partially_ inspired by actual Kamloops photographer Mary Spencer, who shot a few pictures of Bill Miner when he was in legal custody. Miner and Flynn/Spencer were not married, either in the film or in real life. Alan King was an American comedian; the Vancouver-born filmmaker was Allan King, and he made several film for CBC Vancouver before moving east. *sigh*

I always find it fascinating how actual personages are amalgamated in film treatments. Many real people become one character onscreen. Or indeed how they are morphed into something deemed more acceptable to the audience by studios. Thanks for that background on The Grey Fox, Dennis! I’m going to watch that film again.

And on a less entertaining note, I had the opportunity only once to take my mother to a movie. 1969 or 1970…it was called Explosion (since re-branded The Blast) about draft dodgers and explosions…starring various Canadian talent, Cec Linder as I recall…and American action guy, Don Stroud. Lots of Vancouver scenery as I recall…terrible film…my mother forgave me.

That sounds like a combination of labour unrest biopic and disaster flick. Am I on the right track, Bill? Have you seen any sign of the film VHS/DVD/Blu-ray/streaming since?

I get the sense the very late 1960s and early 1970s saw a trend in BC-shot film, a cluster of Hollywood projects coming north. Perhaps because Robert Altman was planning to do so? He was quite an influential filmmaker.