Too good for the NHL

The Longest Shot: How Larry Kwong Changed the Face of Hockey

by Chad Soon and George Chiang, with illustrations by Amy Qi

Victoria: Orca Book Publishers, February 13, 2024

$24.95 / 9781459835030

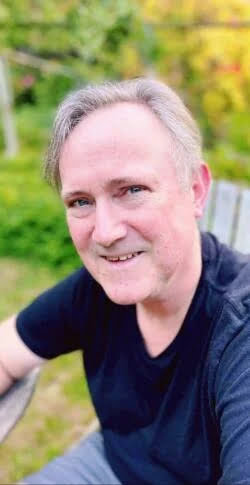

Reviewed by Daniel Gawthrop

*

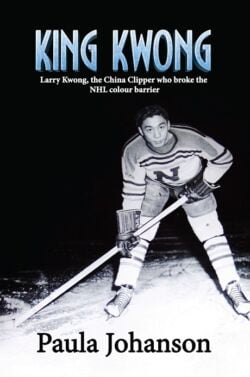

The story of Vernon’s Larry Kwong, the first professional hockey player of Asian descent to crack an NHL line-up, has been told many times. The Province’s Tom Hawthorn, CBC reports, documentaries, and at least one biography (Paula Johanson’s King Kwong) have all mined the archives to share the inspiring tale of a Chinese Canadian who excelled at our national game during a time of anti-Asian racism in society and white supremacy in the sport.

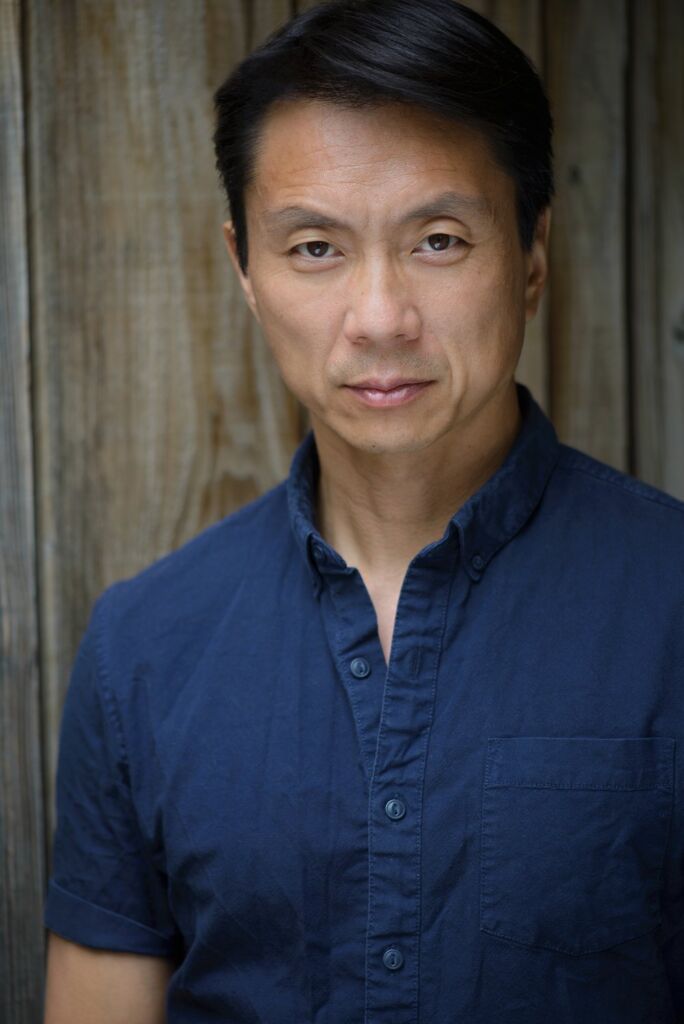

But the hockey legend whose on-ice exploits earned him the nickname “Chinese Clipper” has perhaps had no greater a cheerleader than Chad Soon. A fourth-generation Chinese-Canadian who grew up on Vancouver Island, Soon as a child dreamed of hockey stardom thanks to Kwong’s trailblazing example, which had inspired his own grandfather. As an adult, Soon has carried the torch for Kwong’s legacy since meeting the man in 2007, conducting an ongoing campaign to have his contribution to the game better recognized by the hockey establishment.

He has already succeeded. In his capacity as director of the Greater Vernon Museum & Archives and Okanagan Sports Hall of Fame (OSHF), Soon ensured that Kwong received important accolades while he was still alive: the BC Hockey Hall of Fame Pioneer Award and induction into the OSHF, BC Sports Hall of Fame and Alberta Hockey Hall of Fame. Since his death in 2018 at age ninety-four, Kwong has also been recognized by the federal government—along with fellow former NHLers Paul Jacobs, Henry Elmer “Buddy” Maracle, Fred Sasakamoose, and Willie O’Ree—for historic achievement in breaking the colour barrier.

The NHL, too, has paid tribute. But unlike O’Ree—who was inducted in the “builder” category in the year of Kwong’s death—Kwong has yet to be awarded with the NHL’s highest honour of immortal stardom, membership in the Hockey Hall of Fame (HHoF). This book, aimed at readers aged nine to twelve, is Soon’s latest bid to make that happen.

Teaming up with a pair of fellow Chinese Canadians—children’s author George Chiang and illustrator Amy Qi—Soon makes a convincing case for Kwong’s posthumous induction into the HHoF with an 87-page mini-biography that’s filled with colourful, iconic images and lively prose.

*

The authors remind their young readers of the tremendous odds against Kwong in achieving his hockey dream. Born in 1923, Larry was the 14th of 15 siblings from two mothers. His father, to bring his second wife to Canada in 1904, had to pay the Chinese head tax—which by that time had risen to $500, the equivalent of two years’ wages for an immigrant worker. On July 1 that year, just two weeks after Larry’s birth, the head tax was replaced by the Chinese Exclusion Act, which not only cut off Chinese immigration but separated families through deportation. Canada Day for white folks was Humiliation Day for Chinese Canadians, the authors remind us.

Despite growing up in a racist society that included Canada’s favourite sport, Larry’s favourite refuge was joining his family around the radio on Saturday nights, listening to Foster Hewitt’s play-by-play calls of Toronto Maple Leaf games. From there, the book recounts Larry’s dizzying ascent in the hockey world from the moment he starts playing the game with his brothers on a makeshift rink in a vacant lot outside the family home.

From an early age, Larry’s ambition to become a hockey player is cast not only against his race but also against the scarcity of hockey resources in his hometown: the Okanagan Valley was then best known “for producing apples, not hockey players,” and there were no local arenas to play in. Like other natural athletes who picked up the game in that era, Larry took advantage of winter weather to spend hours honing his skills on frozen ponds.

From his first organized game at age twelve, joining players two years older and scoring all three of his team’s goals in a tie match, the gifted forward became unstoppable. From the midget Hydrophones, playing at Vernon’s new Civic Arena in 1938-39, to the Trail Smoke Eaters, Kwong became a major draw. A beautiful skater who drew fans from their seats with his dazzling moves, he was an artful goal-scorer—including from behind the net, an area that became his “office,” much as it later would for Wayne Gretzky.

Finally discovered by an NHL scout for the New York Rangers, Kwong was assigned to their farm team, the New York Rovers—who also played at Madison Square Garden. The authors note how attendance for Rovers games quickly rose from 2,500 to more than 15,000. Kwong was told he’d get his chance with the big club once he proved himself in the minors. But even as he continued to excel, he watched helplessly as one lesser player after another got called up before him.

When the Rangers finally brought him up on March 13, 1948, for a game against the Canadiens at the Forum in Montreal, he rode the bench until late in the third period, when he skated for a single, 60-second shift. “A New York Minute,” as this section is titled, was all he would get in the NHL. Despite his large fan base, Kwong was up against a mainstream hockey culture that had long presumed the game to be a white man’s sport—a mentality exemplified by the NHL, a xenophobically clubby organization that remains almost cult-like in its resistance to change.

On the other hand, as the authors remind us, Kwong was lucky to have made it at all: “From 1942 to 1967 there were only six teams in the NHL. That meant there were fewer than 100 roster spots. To make the league in the Original Six era was an incredible achievement.”

The remainder of the book covers Kwong’s post-playing life: an exemplary record of community service, in both Canada and Europe, marked by tireless dedication to the cause of expanding access to hockey for Chinese Canadians and other youth.

The Longest Shot comes with an illustrated timeline, a glossary, a list of print, online and film resources, and an index littered with the names of NHL legends—including Jean Beliveau, who raved about Kwong’s play after competing against him in the Quebec Senior Hockey League. It’s also sprinkled with fun facts illustrated by Qi, including this one: “In 2000 the Asian Canadian band Number One Son released a song about Larry Kwong called ‘Hockey Night in Chinatown.’”

By the time they finish this book, young readers of The Longest Shot will be left wondering: why on earth has Larry Kwong been excluded from the Hockey Hall of Fame?

*

Daniel Gawthrop plays left wing with the Cutting Edges, Vancouver’s LGBTQ hockey club, which he co-founded in 1994 after organizing the ice hockey event at Gay Games III in 1990. His debut novel, Double Karma, was published in 2023 by Cormorant Books and reviewed by the British Columbia Review here. He’s also the author of five nonfiction titles including The Rice Queen Diaries, a memoir about interracial attraction. Visit his website here. [Editor’s note: Daniel Gawthrop has reviewed hockey books by Corey Hirsch and Cheryl A. MacDonald and Jonathon R.J. Edwards (editors), as well as books by Valerie Jerome, Niloufar-Lily Soltani, Brett Popplewell, Alex Kazemi, Charlotte Gill, and Eden Robinson for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “Too good for the NHL”

Chad Soon and George Chiang have done a wonderful job of sharing Larry Kwong’s inspiring — and infuriating — story for young readers. It is bizarre, though, to see my name as being associated with The Province, a publication which most recently carried my byline 28 years ago. I first wrote about Larry Kwong for The Globe and Mail in 2001, the first profile of the player as an NHL trailblazer to be published in a national newspaper. I wrote further columns about Larry for the Globe in 2008 and 2010, a feature for TheTyee.ca in 2018, and, a month later, his obituary for the Globe after Larry died at age 94. Over those many years, Chad Soon has indeed been a terrific champion of Larry’s legacy and deserves all credit for Larry and his family receiving recognition from several halls of fame and the NHL.

Thanks, Daniel Gawthrop, for covering Chad and George’s terrific book! And for the shout out to King Kwong, my own bio of hockey hero Larry Kwong. Did you know Chad wrote the afterword for the new edition of my book?