An Everywoman for Iran’s last century

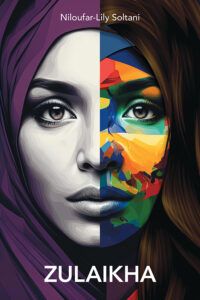

Zulaikha

by Niloufar-Lily Soltani

Toronto: Inanna Publications, 2023

$24.95 / 9781771339568

Reviewed by Daniel Gawthrop

*

For readers with little more than news cycle awareness of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Vancouver’s Niloufar-Lily Soltani offers an intriguing glimpse into a country whose people have endured no end of suffering from the dark legacies of colonial rule and religious extremism.

The title character accounts for much of this novel’s appeal. Women in Iran have always been raised to be silent, obedient, and subservient to men, but Zulaikha—which means “brilliant beauty” in Persian, and “bright and fair” in Arabic, deriving from the exotic and sensual wife of the Pharaoh’s guard, a story told in the Quran, Bible, and Torah—begins as all three and ends as none.

As we follow her path from the age of thirteen under the client state rule of the Shah, through the revolution more than two decades later, followed by decades more of grim fundamentalism under Khomeinist rule, Zulaikha reveals how the status of women has changed little despite knowledge of the outside world.

Her story explores the meaning of love, family loyalty, the struggle for self-expression, and devotion to homeland in times of constant upheaval.

From the start, we get a sense of our heroine’s uphill battle for independence with a sobering lesson from her mother Madineh, who walks her home from the last day of grade six: this was her final school year because “no man would marry a girl with an education.” Instead of attending school, adolescent Zulaikha must work in order to keep the home financially secure. She becomes part of the servant class for the foreigners who employ her.

Zulaikha’s physical presence at formal events is completely ignored. She is seen only as the trays of food and drinks she serves. At one point she moves to Bahrain, where she can earn more. But her life grows dangerous from the moment she flowers into womanhood and learns that men of all classes will not leave her alone.

Early in the novel, it appears that men will be reduced to pathetic beasts of appetite. But Soltani does not oversimplify gender relations. In Zulaikha, the chief male characters are complex figures whose struggles to survive under oppressive rule mirror those of the women.

For example, under the client state rule of the Shah, she reminds us, Iranian men endured the emasculation of having to work for the British Oil Company. “We are all servants of someone,” one adult male character tells a friend who rejects his offer of a job with the Oil Company, while Abu declares, “I am my own man, Jamshid. I am no servant of the British. I belong to the sea.”

Women, of course, experience much worse.

In the late 1950s, Zulaikha’s hometown of Khuzestan not only discouraged education but shamed girls and women who openly expressed any kind of sexuality. In the novel, further, family relations are marked by necessary silences: to avoid dire consequences, self-censorship becomes mandatory. This norm becomes important when the young Zulaikha learns she is pregnant and is forced to have an abortion.

Here Soltani is adept at revealing class divisions in Iranian society: Madineh must convince her daughter to terminate the pregnancy because their family has been deemed unworthy of marriage to the family of the father. Later in the story, Zulaikha compares this traumatic event to the sudden appearance of Jihadist extremism and the lack of acceptance of western liberalism in Iranian society:

They killed a baby just to prevent their family from mixing with hers. Did other people on the city streets experience the same pain and humiliation? Why didn’t she ever scream about an injustice like that? These angry faces and fists aimed to destroy anything in their way. But no such plans for reconstructing or recovering…

Over the course of the story, romantic partners including her husband come in and out of Zulaikha’s life, their departures and long-distance promises indicating their own sense of agency relative to hers. Women are the ones who stay and face the music, who take responsibility for family and home. But when her brother Hessam disappears, presumably a victim of the regime, Zulaikha’s world is overturned.

Slavery is a constant theme—slavery to the state, to oppressively archaic cultural norms—and Soltani effective conveys the sense of paranoia and claustrophobia of living in such a society.

Although defiant of the Revolutionary Guards—she ridicules a pair of young conscripts who show up at her home to take away her computer and satellite dish because of a single visit by a political undesirable—Zulaikha finds interrogation a terrifying ordeal. Later, she meets a woman who has learned, all too late, the folly of thinking Canadian citizenship could prevent an Iranian woman from being held in prison in Tehran. Here, Soltani reminds the reader of multiple cases of Iranian Canadian women who have suffered that very fate.

* *

Zulaikha is sometimes hard to follow, thanks to the novel’s voluminous cast of characters. Apart from the most prominent—Zulaikha, her mother, two brothers, husband, and son—there are at least eighteen characters with varying degrees of importance throughout the narrative. The book provides a list to identify them, but they sometimes get lost in Soltani’s fast-paced, dialogue-driven prose—and a linear narrative form that—apart from a prologue, “Two Airports,” that foreshadows from the present—unfolds chronologically.

A labour of love, Zulaikha took the author many years to complete. Perhaps that is why there is something of a one-and-done feeling about this novel—a sense that Soltani, who was born in Iran, was so emotionally invested in this project that she left everything on the table to publish her first and possibly only venture into long-form literary fiction.

I’ll be happy to be proven wrong. But if I’m right, Soltani can rest assured that she has created a character in Zulaikha, an Everywoman for Iran’s last century and worthy of film treatment.

*

Daniel Gawthrop‘s debut novel, Double Karma, was published in 2023 by Cormorant Books. He’s also the author of five nonfiction titles including The Rice Queen Diaries, a memoir about interracial attraction. Visit his website here. [Editor’s note: Daniel Gawthrop has reviewed books by Brett Popplewell, Alex Kazemi, Charlotte Gill, Eden Robinson, Tsering Yangzom Lama, Alan Haig-Brown, and Anthony Varesi for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (nonfiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “An Everywoman for Iran’s last century”