Hard knock lives, revisited

A brief relief from hunger

by Spenser Smith

Guelph: Gordon Hill Press, 2023

$20.00 / 9781774220986

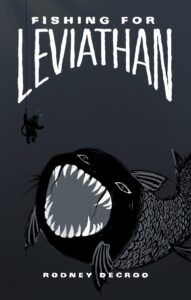

Fishing for Leviathan

by Rodney DeCroo

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2023

$18.00 / 9781772142136

Reviewed by Joe Enns

*

Two writers explore their roles in society while coping with addiction, resulting in different poetic responses.

What is the connection between hunger and bravery, and on the flip side, shame? Spenser Smith pulls these threads together in a societal context in A brief relief from hunger, his debut poetry collection. A brief relief from hunger is an urgent rationale for persistence (“…survival / is like a hammered nail—it absorbs // blow after blow and makes a home / out of pressure…”) in the face of a persecution against addiction. Smith creates his own refuge from a proposed eugenic society—ie, “Crime rate is dropping like junkies. Love it. // https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culling”—by building empathy for the speaker who’s happy “frying perogies for Grandma because she says I fry them best.”

A longtime Vancouver resident recently relocated to Winnipeg, Smith interrogates the nature of society through online news reports, social media comments sections, and field notes from family work experience (“I am a man without an interest in hammers”). Many of the poems read like confessional letters to loved ones (for instance, “I carry your voice in my pocket and summon it like a dose of naloxone”), or friends who’ve passed away, although this collection contains a variety of forms and tones. Each poem works towards a cause: showing the humanity underpinning addiction through empathy and real-life imagery.

The experimental forms and interwoven imagery (owls, hunger, poison, and bodies) keep the reader interested as they sketch aspects of the speaker’s lived experience that is accessible (even though the subject may work to repel some readers: “…I am a dirty sock. My brothers are dirty socks. My family, a mound of dirty socks”). These opposing forces balance each other.

Smith’s work is innovative and inventive in an appreciable way. One poem, “Hundreds of Men: A Case Study,” experiments with form the most. The poet uses a collection of field notes, quotes from conversations, and lists to create a window into the speaker’s experience of family, culture, work, and a history of hammers. Smith’s keen observations and humour offset otherwise heart-wrenching realities. In a different context, Smith incorporates social media comments taken from news reports and Facebook. Much of the verbiage revolves around the consequential (Darwinian selection) and unethical culling of addicts (“It would be cheaper to clean up the dead junkies than saving their lives on a weekly, even daily basis…”). Smith responds, not with anger, but by presenting a complex view of an addict’s life: “we ate like equals.”

In Smith’s book, everyone has a hunger (“I ate Big Macs so I could quit drugs. I used drugs because I could not stomach shame”), and even an owl is vulnerable to poison, but the author shows that with each bite, we can find relief.

Fishing for Leviathan is the third book of poetry by Vancouver’s Rodney DeCroo (Next Door to the Butcher Shop). It hits like a “a riot of self-pity in a filthy apartment.”

In the poem titled “A Political Poem,” DeCroo writes, “Okay, so now you’re saying I got a chip / on my shoulder. Well, you’re wrong. / It’s more like a fucking brick— / and one of these days / I’m gonna throw it through / the front window of a bank,” and these lines sum up the tone and themes of this collection. Through each nostalgic and confessional poem, DeCroo paints a portrait of a torn man roaming the gloomy underbelly of U.S. and Canada—“a darker shape within the blackness— / a shadow slowly becoming a man”—as he searches for something he can’t define.

The epigraph to the book is a biblical verse from the Book of Job with a reference to Leviathan and the action of pressing Leviathan’s tongue down with a cord. DeCroo extends this tortured man archetype (“I thought I was in hell. / I didn’t know anything”) across each reflective line that drips with sentimentality. Fishing for Leviathon balances agonistic machismo with self-deprecation in a sort of nostalgic rant.

Most of the poems in the collection are narrative free verse with no stanza breaks, lacking most poetic devices. Often the poems also lack a turn or hinge, or even a so-what moment or ultimate insight, relying on the shock of the imagery to move the viewer.

The strongest poems, however, vary the form, especially using couplets and disjointed imagery. For example, in “Salt” (possibly the strongest of the book), DeCroo weaves together a wandering train of thought that makes full use of word play, imagery, and mythology: “…I say the word / ‘apparently a lot / and also ‘a lot’. An angel turned Lot’s // wife into a pillar of salt for sneaking / a peek. Apparently, angels are // morally neutral.”

“Flash Grenades” employs a similar form and technique—“…When the muses / finally decide to transfigure me // I’ll blind everyone like a flash grenade / exploding in a waiting room…”—and the impact of these more formal, less narrative poems is noticeable.

One poetic device that DeCroo doesn’t shy away is similes, often drawing out comparisons to such a length that the reader can forget what the speaker was talking about in the first place: “dashboard lights / glow like white windows // of distant skyscrapers / over an empty downtown // or lights of tugboats / working the river at night.”

DeCroo strains towards the shadows of authors like Charles Bukowski and Hunter S. Thompson but falls short of any underlying complex significance. Yet DeCroo seems fully aware of this, frequently commenting on criticisms of his work: “You might also say that this / isn’t a poem. Where are the metaphors,” and “Once you said my poems / were like chickens, incapable of flight.” DeCroo’s poetry reads like confessional letters and an interrogation of life and poetry, however, unlike Smith’s work, Fishing for Leviathan fails to tap into any moral or honest empathy.

*

Joe Enns is a Canadian writer, painter, and fisheries biologist on Vancouver Island. His writing has appeared in The Dalhousie Review, FreeFall, The Fiddlehead, GUSTS, and Portal Magazine, and book reviews in The Malahat Review and The British Columbia Review. Joe has a BA in Creative Writing and a BSc in Ecological Restoration. [Editor’s note: Joe has reviewed Barbara Pelman, Karl Meade, M.W. Jaeggle, Ali Blythe, Emily Osborne, Will Goede, and Evelyn Lau for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Hard knock lives, revisited”