Dispossessed and exploited

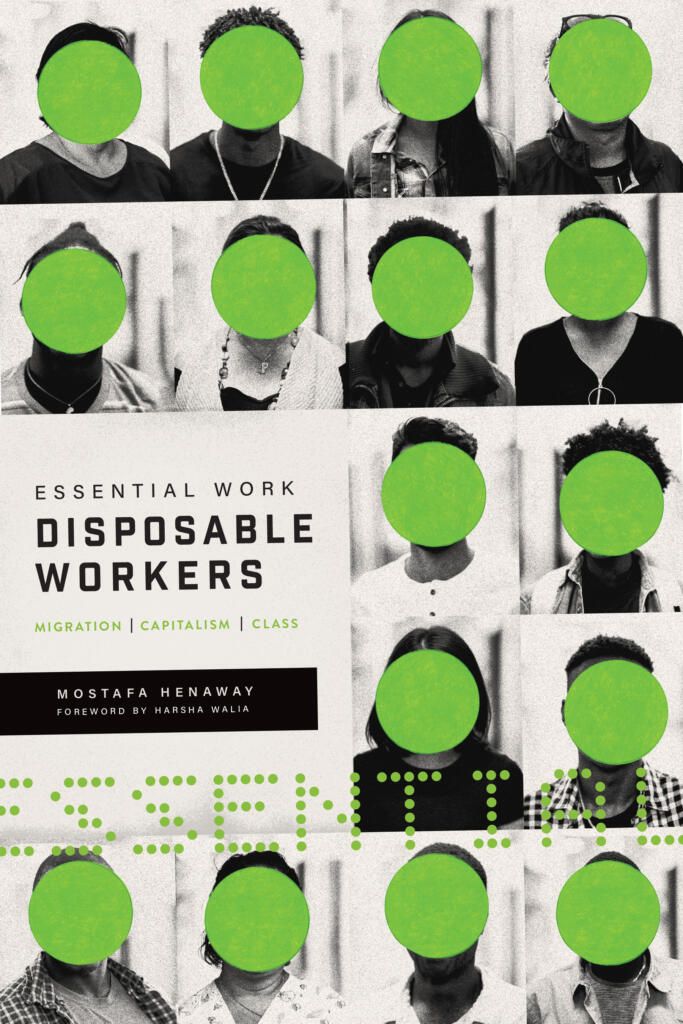

Essential Work, Disposable Workers: Migration, Capitalism and Class

by Mostafa Henaway

Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2023

$27 / 9781773632254

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

In the 1990s, I worked for the Canadian Union of Public Employees and part of the job was to battle against the four horsemen of modern capitalism: privatization, deregulation, free trade, and globalization. If the horsemen were unleashed, we predicted a future where working people’s lives would be worsened. Now the future is here, and Essential Work, Disposable Workers illustrates what it looks like particularly for immigrant workers.

The labour movement mounted several campaigns against the shifting priorities of the multinational corporate world and complicit western governments. When profits go down, social and economic changes are needed to ensure they don’t drop further. One shift, already in evidence in the 1990s, was the increase in migrant labour.

Today, we are shocked when we read about another overloaded boat attempting to land in Italy, Greece, or another Mediterranean country, too often resulting in accidents and deaths at sea. Mostafa Henaway reveals that this is no accident. Rather, it is by design, a byproduct of the neoliberal system. It is a built-in exchange, he argues persuasively: cheap labour that yields more profits for American and western European corporations. But there is another benefit, a tragic one.

The World Bank and International Monetary Fund facilitated this labour exchange by demanding that poorer southern countries ‘structurally adjust’ their economies, forcing them to abandon traditional crops and products so that northern countries could enjoy middle-class lives. Poor countries, their economies now dependent on labour-hungry industrial economies, benefit because the constantly migrating workers, doing precarious work at low wages without union protection, send millions of dollars in remittances back home to assist families.

Henaway shows that the exchange of impermanent migrant labour for those remittances is a systematic, and often racist, part of the new world economy. “The massive migration of people to the advanced capitalist economies has coincided with their integration into neoliberal globalization,” he argues. “Migrants are central to the functioning and reproduction of global capitalism itself.”

Mexico, the Philippines, South and Southeast Asia, Egypt, and Latin America have been reshaped into models of labour-exporting states. Instead of shipping products to consumers in the Global North, Henaway says, they are shipping people. And reshipping them when immigration polices such as those in Canada often reject the imports as unacceptable for permanent residency and ultimately citizenship.

They are caught between abject poverty in their home countries and a never-ending revolving door of unemployment and precarious work here. Henaway uses what he calls “platform based corporations” or “platform capitalism” to illustrate how migrant workers are rendered invisible thus avoiding unionization.

They are vulnerable to shiftless recruitment agencies and employers who either don’t know or don’t care that the agencies perpetuate a system that benefits these platform corporations by sustaining global labour supply chains.

“Gig” workers, such as those working for Uber, Amazon, or large food-delivery corporations, are “falsely classified as self-employed.” That means employers do not have to treat them as employees with all the pay and benefits that entails. Women employed in this platform economy are particular targets for abusive employer behaviour. It is “highly gendered and racialized” labour, Henaway notes.

There is anger and frustration in these pages and it sometimes spills out as rhetoric. It is Henaway sounding the alarm to the dangers ahead for not just immigrant workers but for all of us. He documents the reason for that alarm, the same one we tried to sound back in the mid-1990s only now there is evidence proving the predictions correct.

But there is also optimism in Disposable Workers. He describes the success of Chris Smalls and Derrick Palmer, who organized a big Amazon warehouse in the United States. They were able to unionize the large workforce because, like Heneway, they come from the same background as the other workers.

He is also optimistic when he sees grassroots organizations springing up to fight exploitation in workplaces, in street protests, and in the courts. His own organization in Montreal, the Immigrant Workers’ Centre, campaigns for the rights of immigrant workers and it joins others in that international fight.

He calls on the broader labour-left to help “build mass organizations and membership-led organizations that give workers leadership, voice and power,” adding “[w]e need to learn and act in solidarity.” It is a worthy goal and possibly the only solution to the labour-migration circle game.

Remembering back to the 1990s and labour’s attempts to stem the economic shift led by the four horsemen of neoliberalism, I am reminded that we paid lip service to that call. Had we known what Henaway has documented, we should have tried even harder.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker. He is among the original contributors to The British Columbia Review. His latest book is Printer’s Devils: How a Feisty Pioneer Newspaper Shaped the History of British Columbia, 1895-1925 (Caitlin Press, 2023). [Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Kennedy Stewart, Henry Tsang, Robert Lower, Benjamin Isitt & Ravi Malhotra, Marc Edge, and Bobbi Hunter (editor) for The British Columbia Review, and he has contributed an essay on trade unionist Harvey Murphy.] Ron lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “Dispossessed and exploited”