Self-knowledge and lashings of eroticism

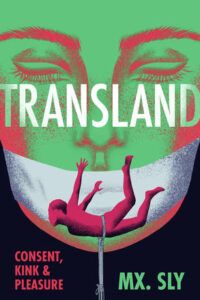

Transland: Consent, Kink & Pleasure

by Mx. Sly

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2023

$24.95 / 9781551529318

Reviewed by Carellin Brooks

*

In the opening pages of Transland, we first encounter our narrator at the regular Women’s and Trans-Only Night held in a Toronto sex club called Fountain.

At the club, Sly, who uses no last name and goes by they/them pronouns, delivers a self-described “stump speech” that’s exacting, precise, and unbending.

The words turn out to consist of an exhaustive catalogue of how Sly will and won’t engage with potential play partners.

This list of boundaries, the reader discovers, mostly ends up being about what Sly dislikes; it’s a menu of conditions.

As Sly outlines the parameters to a potential play partner, the reader can’t help but wonder at the seriousness of their tone:

I don’t play with humiliation. I don’t like to be laughed at or made fun of, ever. I don’t want to hear what you think about the way I look, even if you think you’re paying me a compliment. During the scene, no one else talks to me, comes near me, or touches me—and if someone tries to, you have to stop them. I like sting pain, not thud pain. Thud pain is like being hit with a baseball bat. Thud pain makes me angry, and it takes me out of the moment. If I feel thud pain, the scene will end immediately.

But before you dismiss Sly as a fetish Van Halen—the band famous for stipulating that there be no brown M&Ms in the dressing room—they surprise you. Here, for example, is their casually razor-sharp assessment of a potential playmate: “She’s a twenty-three-year-old actor with blonde hair and blue eyes, and her special acting skills include being young, being hot, and playing the ukulele.”

Of course Sly and the actor get together—with such special skills, who could resist? Scavenging behind an unattended bar for cling wrap to use in the mummification scene they’ve decided to enact, others in the room pause in their own adventures to wonderingly ask: “You’re stealing from the bar and you aren’t stealing booze?”

This kind of humour punctuates the more sober moments in Transland, an unflinching exploration of self-knowledge and self-deception with lashings (sorry, couldn’t resist) of eroticism.

Scenes (many set in Vancouver and Burnaby, where Sly worked in the arts before relocating to Australia) are conveyed with an abundance of sensory detail, like the smell and texture of rope used in shibari, Japanese rope bondage: “When I’m being tied, the tension against my skin of individual strands of raw jute wound into rope scratches all of my nerve endings simultaneously, with every move I make… The environment it came from will always be trapped in its fibres, earthy and wet.”

There are two themes in Transland: the author’s growing self-awareness and their growing awareness of the deficits of the subculture. Here, for example, Sly explains how shibari replicates typical societal understandings of gender: “The greatest form of heteroflexibility present is that most of the straight dudes in the rope scene are deeply emotionally invested in how they’re perceived by each other,” meaning that the riggers, or men wielding the ropes, increase their status by attracting more conventionally sexy female partners. As Sly comments caustically, “as if treating assigned-female-at-birth bodies as status symbols is a novel idea.”

This particular form of one-upmanship culminates in a party at a soulless Toronto condo where Sly internally excoriates the male tops who pass around images of their pretty, feminine female bottoms like trading cards. But Sly doesn’t also questions their own willingness to put up with such antithetical politics for a chance to play.

Indeed, when Sly begins playing with a male dominant and his female submissive met at the party, a date turns ugly: the male dom “accidently” shoots a video of their sexual activities without Sly’s permission, leaving them feeling, in their own words, “angry, trapped, scared, gaslit, and voiceless.”

It is a truism that people are drawn to bondage, domination, submission, and masochism (BDSM) to feel just the opposite. Sexually bounded and freely chosen violence, the theory goes, is not just hot, but helps people heal from the wounds in their pasts. “Hit me,” says a masochist, and then, “Stop.” Being able to choose pain and erect boundaries rewrites scripts where players were once victimized and too young to resist.

This is the journey that Sly takes and, though I suspect it is one that has been tidied up for the purposes of narrative unity, it makes for a satisfying read.

There was only one place where I felt myself longing for more. Sly spends much of Transland understandably focused on their own experience as a bottom, and part of the remainder dissecting the sexist politics of a scene where their gender is not addressed in any meaningful way. The only thing missing is an exploration of what motivates their tops.

For instance, the portraits of James, the Aussie man who tenderly ties them, or of Evie, the femmedom who plays with Sly when not topping male paying customers, made me want to learn what the payoff was for them. A good top is hard to find, and I wondered in particular where the professional dominatrix got off, except in having her expertise and mistressry (yes, I just made up that word) confirmed.

That aside, if you’ve ever wondered what it feels like to be trussed to a jungle gym while a beautiful woman slowly pushes her stiletto boot into your mouth, this is the book for you.

Transland also makes an excellent gift for anyone kinky in your life, or, for the neophyte, an equally excellent way to understand the fetish and BDSM subcultures from an insider’s perspective.

Finally, if you’re curious about how people construct their sexual lives to meet their deepest needs—and who isn’t?—I can’t recommend this book highly enough.

*

Carellin Brooks is the author of the poetry collection Learned (Book*hug, 2022) and four other books. She lives in Vancouver. [Editor’s note: Learned (Book*hug, 2022), a poetry collection about Brooks’ time at Oxford and in the fleshpots of London, was reviewed in BCR by Linda Rogers. Brooks recently reviewed Debbie Bateman, Michael V. Smith, Buffy Cram and Maryanna Gabriel for BCR.]

*

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Self-knowledge and lashings of eroticism”