Travels of ‘an imperfect messenger’

Naked In A Pyramid: Travels & Observations

by Yosef Wosk

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2023

$22 / 9781772142204

Reviewed by Trevor Carolan

*

If you’re bookish you’ve heard of Yosef Wosk. Collector, activist, philanthropist, former rabbi, supporter of literary awards—he’s kept his hand in. Then a few years back a travel account by him appeared in a literary journal. “Naked In A Pyramid” recounted a 1984 journey of his to the 4700-year-old Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara in Egypt. Climbing the pyramids is illegal, but Wosk relates his compulsion to scale Pharoah Khufu’s mausoleum on a full moon night. It’s a heckuva tale. Part of its draw comes from Wosk’s sheer terror of the steep height, but he survives to reach the summit.

Next day he’s at it again, doing his trogg thing with a small group from Jean Houston’s Mystery School. Dank, pitch-black, claustrophobia-inducing, the tunnels beneath the gigantic stone pile beckon him to enter and explore. The oxygen is thin, and for twenty minutes he and his colleagues inch down a burial tunnel reeking of urine. Anyone who’s explored these druidic ventures knows they pack a cosmic wallop that lifts us back to some sort of beginningless time. Wosk fades off alone in the gloom. It’s an ideal moment to…Well, to do what precisely? Some freak out, he says, start feeling the walls looking for a sign of light, for a way out. Instead, Wosk removes his clothes, sits naked in silence, meditating on the Big Void. He has a bottle of water, his prayer texts, his phylacteries. Things start getting spiritual, even a little nutty when a whiff of the profane enters with thoughts of what other taboo acts must surely have taken place in this dark corner. How long is he there? Long enough for the metaphysics to kick in. From the biblical tribe of Levi, thousands of years of history and prophecy link him to the Numinal, the Sublime. His tale is a blast, even a little blasphemous in an Oscar Wildean sort of way. But this is only his first account in a whole book of travel tales and observations wherein Wosk from the well-regarded appliance-dealing family That Will Not Be Undersold reveals himself as a bit of a wild Oscar from the get-go. Emerging from the stony tomb “overflowing with gratitude,” he feels ‘Reborn, wrung from the birth canal all over again.” It’s outrageous.

A segue into the enduring phenomenon of Marilyn Monroe, “a tender touchstone for empathy” ensues. “Adored by millions, she was lonely” he remarks: “She had a short, convoluted, fabulous, tortuous, successful, manipulated life…She became a symbol, a mythic archetype, and bore the burden of our projections. It killed her. We killed her.” Wosk remembers the day she died, where he was on August 4, 1962—on a family holiday at Penticton’s Crown Motel. He recalls the shock headlines of the newspapers. At thirteen, it was his first conscious experience “of someone committing suicide because of life trauma.” Years later, after a succession of other popstars follow—Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Amy Winehouse, Elvis, Kurt Cobain, Brian Jones, “I saw a pattern,” he concludes, “and thought about the pressures of success.” The pathology of buying into fame and celebrity, he recognizes, “often comes with a death sentence.” In this, Wosk shifts steadily toward a philosophical inquiry into his life and times. Decades later, he writes of how he was compelled to examine his own path as a public personage, surrendering numerous administrative roles, retiring from SFU, leaving awkward family dealings, and settling quietly on an island. More importantly he hit the road: Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Sino-Japanese territory, and circumnavigated the globe. Increasingly aware of the “physical correspondences between geography and body, as well as the emotional, spiritual and intellectual relationships between the global brain and the extended human mind,” he turned to writing—not yet ready, he contends, “to check out of Motel Earth.”

His book is testament to this extended period of searching and for encounters with enlightened teachers.

In 2011, Wosk was called to visit the grave of Dostoevsky while in Russia. Standing before the writer’s reliquary, the Canadian engages in a searching conversation with Fyodor’s spirit. Is he a good enough writer? What if he’s mocked, rejected? When the haunting voice of the Russian incants back, Wosk kicks into prose overdrive as the response he yearns for unwinds. Then, unsurprising in a churchyard, there’s stillness and recognition that “not a word was spoken but much had been said.”

Long narrative accounts in poetry and prose recount journeys to both the South and North Poles, reporting on some of the group odysseys Wosk has undertaken to these “final terrestrial” frontiers. Neither canned magazine junkets where alpine hikes lead to martinis in venerable hotels, nor Dervla Murphy-style solo voyages where the traveller faces up to extended hardship, these are—as Wosk understands—adventures. With rugged modern air transport to cover vast distances, ice-breakers to crush through a continent that’s really a frozen sea, or aboard all-terrain motor rigs, there’s hardship, sure; however, in a revealing moment he explains there was more at stake than simply pure physical journey. These walkabouts in “reaching a geographic extreme” were steps, he claims, “in shamanic psychogeography.”

Did you catch that? Shamanic psychogeography. Check your backpack straps: we’re heading for the higher heights. I’ll take this traveller’s word for what it’s like at the magnetic tip of either pole. “It’s too cold to kneel and kiss the ground,” he tells us, some lines after meditating on the horrors of the Odessa and Pinsk pogroms that drove his parents’ families to Canada. “Time and space are abstract here…All the earth’s 24 time zones meet at this point.” Cosmically, there’s only one thing to do: “I pass through all time zones and/complete a walkabout of the planet./No jet lag for having travelled twenty-four hours/in a matter of seconds/and no exhaustion for having encircled the planet.” There’s more, naturally; every sort of landscape description, catalogues of birds, whales, sundry mammals; but what’s not to like about a zany mystic who still knows when to hit the cruise-control?

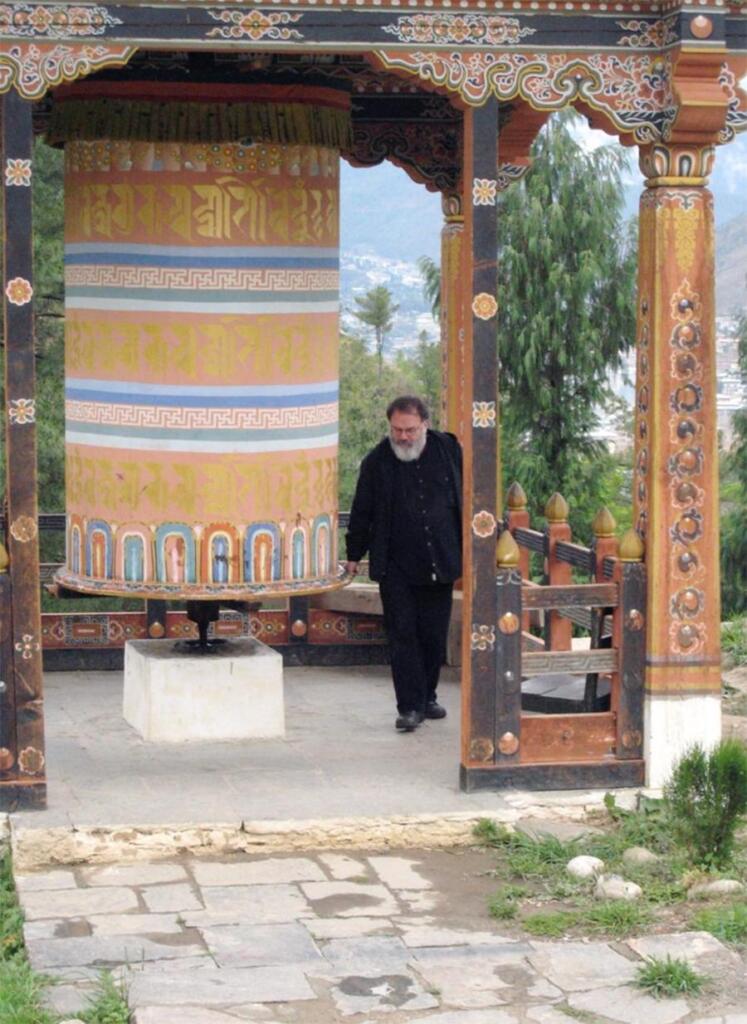

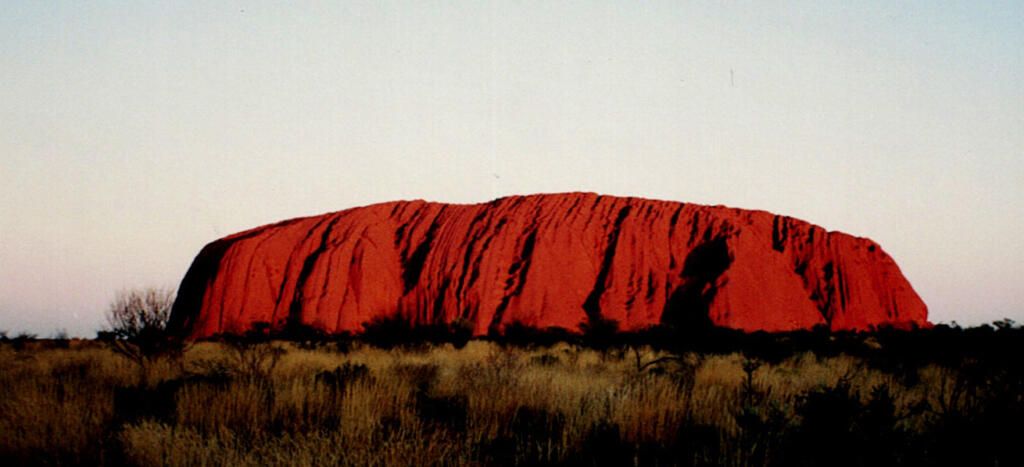

Travel is a powerful yen and like opium it’s hard to put the pipe down. A lengthy collage entitled “Fool’s Journey” dishes up recollections from the scores of destinations Wosk has banked in his wanderings. Like the old road-bum tune “I’ve been Everywhere”, the author unfurls a logbook linking Borobudur, Angkor Wat, Cuba’s Viñales Valley, the rubble of ancient Carthage, Guatemala’s Mayan temples, China’s Heaven Peaks, Haida Gwaii, and Europe’s old holocaust ghettos, among others. Sounding like an ancient Mariner, his litany is shared, he says, “not as a boast but an obligation.” Finding “more grounds for worship” while roaming, he stops for prayer before ancient trees and mountains, Jerusalem’s timeless religious shrines, in Catholic and Orthodox cathedrals, and before India’s holy Ganga, for as he avers, “each step we take creates echoes in the landscape as well as the soul.” Appropriately, on a tramp through Australia’s outback to sacred red-rock Uluru, he records his ecumenical awe at standing before the “oldest living cultural history in the world, extending back some 65,000 years.”

Photo Trevor Marc Hughes

Wosk expresses a profound, East Asian-like regard for particular teachers, and his appreciations of Leonard Cohen and Elie Wiesel are revealing. Cohen, whom he never met, and Wiesel with whom he studied for five years at Boston University, earn his admiration for their upholding of prophetic roles within Jewish tradition. Both were devoted to music, he explains—the singer-poet, and the storyteller of civilizational conscience. From biblical times the prophet’s role, he clarifies, was “responsibility, not bliss; it implied the imperative to speak out, to act, to warn, to challenge, and ultimately to console.” The pair left the world a better place for having passed our way, he suggests, and were, “like us…imperfect, both broken, both striving for wholeness: that’s how the light got in.”

The book rounds out with an affectionate memoir of his family and a Vancouver Jewish upbringing that has something of Mordecai Richler’s St Urbain Street ethos to it. Hard-up immigrant life after an exodus from Eastern Europe; peddling pots and pans from a horse-and-cart, scrap furniture, early shopfronts, then the bold appliance store chain that with its catchy CKNW radio jingles made Wosk’s a west coast household name for a couple of generations. In the process, Wosk’s father Morris, also became a significant property developer—the Blue Horizon and Blue Boy hotels are Wosk legacies. He made contributions too, as a civic-minded man with a gilt-edged record of both larger public and Jewish community service alike—one of those who Stephen Spender wrote that “left the vivid air signed with their honour.” The Wosks had style back when that still meant something. These things have a way of rubbing off.

The author’s own search for meaning leads him on wide-ranging voyages after competitive athletics in high school and Arts One study at UBC—useful in instilling humility and pride in accomplishment. Years of religious study in Israel, New York, and Philadelphia follow, then service as a congregational rabbi. He’s up front about his entheogenic explorations, and seven years’ study off and on with pioneering Human Potential Movement psychologist Jean Houston.

Near the book’s closing, Wosk notes that while earning his PhD, his mentors were Dr Thomas Berry, the cultural historian, Passionist priest, Buddhist scholar, and author of The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future, and Rabbi Dr. Zalman Schacter-Shalomi from the Jewish Renewal Movement. It’s an experience that could easily pass as another checklist item, but consider what doors of perception these titans represented: Berry—the eminence gris of the global environmental movement, who named our period of eco-crisis ‘The Ecozoic Age’ for its disturbed imbalances between Earth, industrial societies, and consciousness; and the Rabbi, who studied with Timothy Leary, and in turn would grant Wosk his second religious ordination as a Maggid—a “traditional Jewish itinerant preacher, skilled as a narrator of Torah and religious stories.”

Ōm Shalom!

Wosk is honest enough to declare himself “an imperfect messenger.” Yet these are the kind of generational “travel” stories that are easy to love, the trail-markings of “a lost and found pilgrim on the road to apotheosis.”

*

Trevor Carolan teaches Environmental Studies at UFV. His Road Trips: Journeys in the Unspoiled World is published by Mother Tongue.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

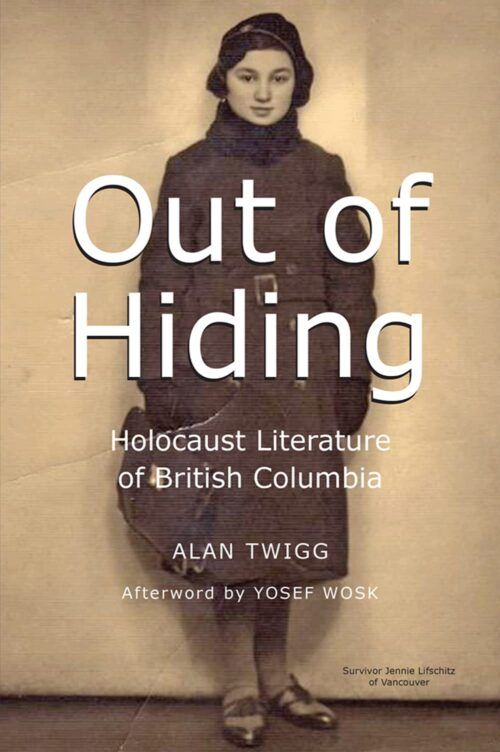

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Travels of ‘an imperfect messenger’”