1586 Touching down in the past

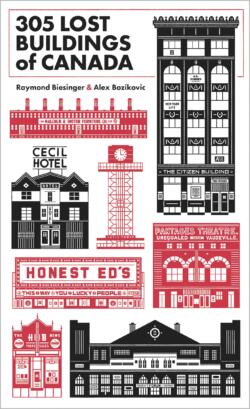

305 Lost Buildings of Canada

by Raymond Biesinger & Alex Bozikovic

Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2022

$22.95 / 9781773102368

Reviewed by Martin Segger

*

What do we do about dead buildings? In our own time do they just sort of fade in community memory, like the guy in the office several cubicles down the hall who retires? He goes. His name plate disappears. After a while we forget he was ever there. We have trouble remembering his name. Finally, we can’t even recall his face. Gone.

What do we do about dead buildings? In our own time do they just sort of fade in community memory, like the guy in the office several cubicles down the hall who retires? He goes. His name plate disappears. After a while we forget he was ever there. We have trouble remembering his name. Finally, we can’t even recall his face. Gone.

Official architectural history ponders over ruins when they survive. Professional conservation theory cautions against ever reconstructing them. Attempts to resurrect architectural masterpieces via graphic reconstructions are often dismissed as “fanciful.” Even more computer generated ones. There is no shortage of architectural histories of the world. Despite my scouring the exhaustive (and authoritative) bibliographic tentacles of Google Search I was unable to locate a “World History of Demolitions.” Odd when you think about.

Except not quite. Academic attempts at addressing the topic are rare. Constance M. Greiff set out to do so in Lost America: from the Mississippi to the Pacific (1972), a rough ride across an architectural landscape from teepees to temple banks. But more commonly they assume the form of topical monographs. Probably most successful in Canada was Luc D’Iberville-Moreau’s Lost Montreal (Oxford University Press, 1975). Such treatises rely heavily on historic (usually Victorian) photographic records which must be interpreted through the aesthetic bias of the Romantic Picturesque lens.

There is indeed more popular nostalgia-inducing literature bearing such titles such as “Then and now…” British Columbia has produced a rich vein of writing on the related general topic of “here today, gone tomorrow,” a sort of riff on the eighteenth century cult of ruins which spotlights buildings whose pending demise seems close to imminent in the eyes of the authors. An early British Columbia example is Taken by the Wind: Vanishing Architecture of the West (1977). Ron Woodall’s view-finder along with T.H. Watkins’ text meditate on remnants of frontier shop fronts and abandoned farm machinery as they sojourn across the western plains.

Also in the seventies, Georgia Straight editor Rowland Morgan planned a series of Then and Now books. Three were produced: B.C. Then and Now: Okanagan/ Kootenay/ Cariboo (Bodima Books, 1976), Victoria (Bodima Books, 1977), and Vancouver (Bodima, 1977). Rowland (aka Roland) Morgan then went on to produce them for several major American cities including Seattle, Honolulu, and San Francisco. They featured his own gritty photography paired with archival views of the same site. More recently Francis Mansbridge has upped the ante in this format with his more lavish Vancouver Then and Now (Thunder Bay Press 2010 and subsequent editions).

Artists seem particularly inspired by such imaginings: from the draftsmanship of Rudi Dangelmaier’s Pioneer Buildings of British Columbia (Harbour, 1989, with an introduction by yours truly) to the watercolour evocations, en plein air or recalled from memory, by Michael Kluckner: Vanishing British Columbia (UBC Press, 2005), and Here & Gone: Artwork of Vancouver & Beyond (Midtown, 2020).

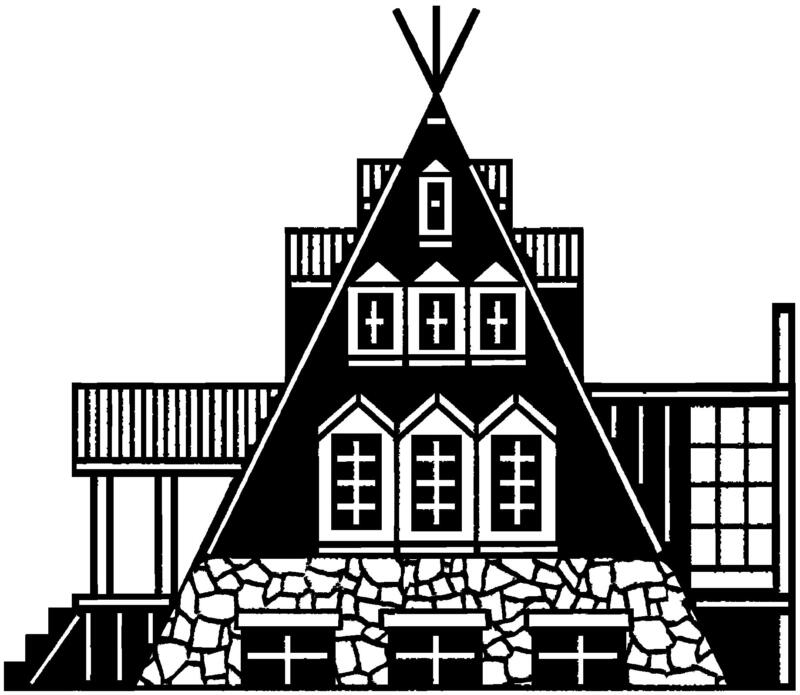

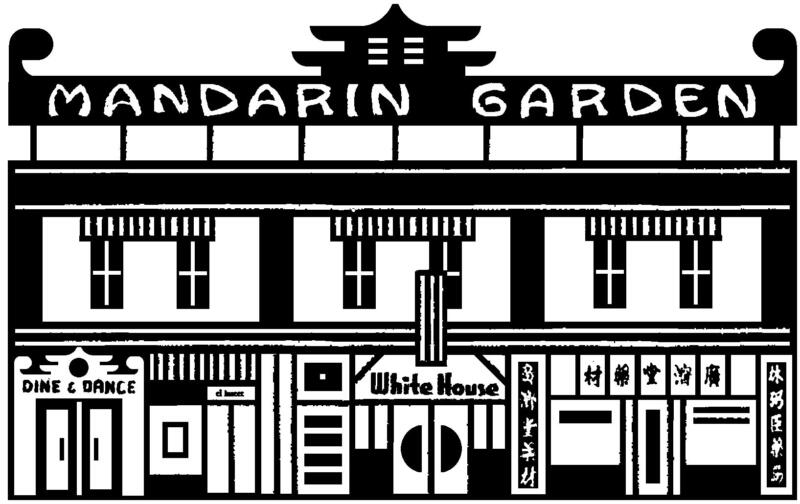

Biesinger and Bozikovic eschew both academic pretensions and the rose-coloured lure of nostalgia. From the almost clinically spare design of the book by Julie Scriver, the creative but simple table of contents marked on a map of Canada, the brevity of the Bozikovic’s factual text (building title, dates, architect, history, description, location (150 words max per entry), to the rhythm of Biesinger’s (mostly two per page) black-and-white woodcut style illustrations, for 200 pages exactly excluding the casing.

We move rapidly across the country, east to west, touching down on 31 cities from Newfoundland to British Columbia, with Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut excluded. For the benefit of this journal’s readership, British Columbia includes Victoria, Greater Vancouver, and Kelowna for a total of 39 lost buildings.

Choices range over dates and types. The earliest is Thomas Trounce’s 1858 Italianate Villa in James Bay, Victoria; the most recent Erickson & Massey’s 1963 David Graham House in West Vancouver. The typology is also wide, ranging from Vancouver’s one monumental pile, Francis Swale’s Hotel Vancouver (1916-1949), to the chopped off remnant of the Canadian Pacific coastal steamer, Princess Mary (1910-2011), which ended its days beached as a popular restaurant in the industrial zone on Victoria’s Upper Harbour.

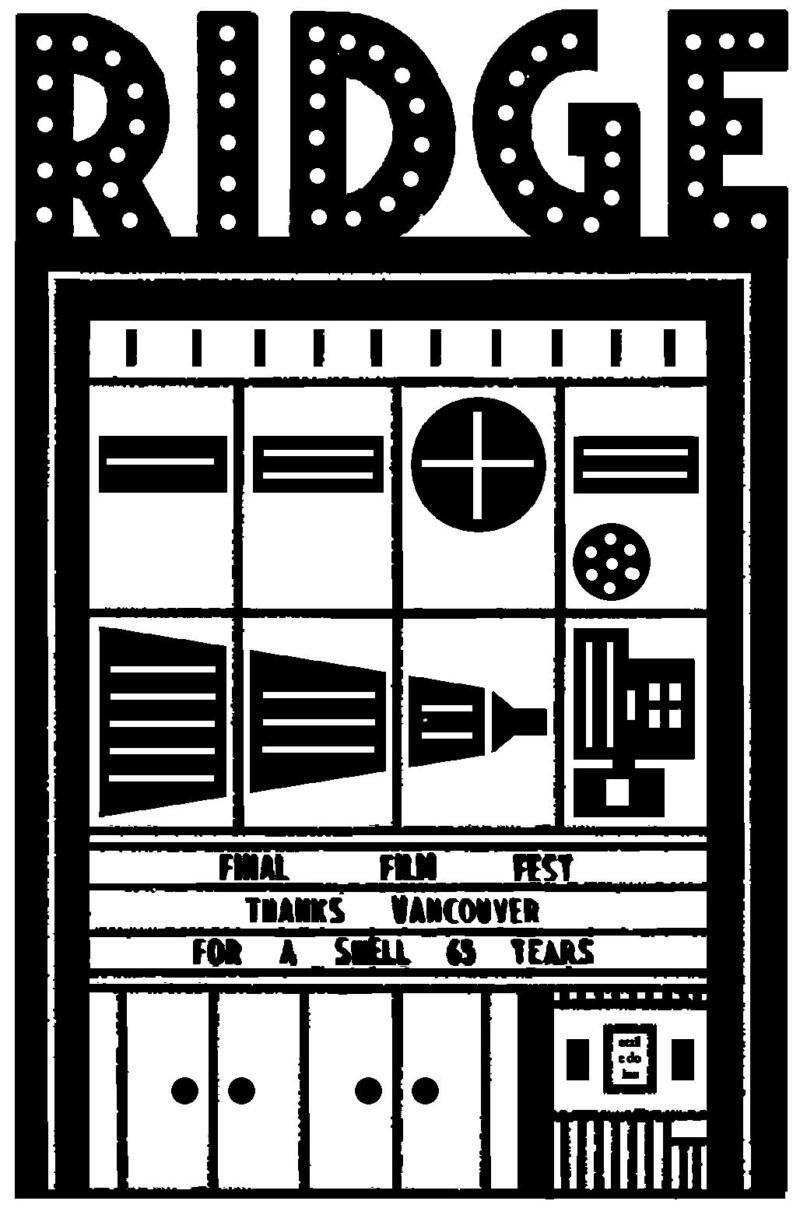

Some choices are obvious, such as fondly remembered community hubs: Kaplan & Sprachman’s Ridge Theatre (1950-2013) on Arbutus Street, Vancouver; E.E. Blackmore’s Mandarin Garden (1918-1952) an icon of its type on South Pender, Vancouver; or a real oddity, included just to prove this is after-all land-of-the-hippies British Columbia, the Stocks Meadow Commune, address unknown outside Kelowna, architect — there probably wasn’t one — and date of construction equally vague. Construction materials: cob, essentially mud, straw and sand. So, guaranteeing it a vita brevis.

Entries include notes as to the current replacements of these monuments although we can forgive the occasional misstep. The foreboding and uncelebrated military-style landmark labelled as the Federal (but actually Dominion) Immigration Detention Hospital in James Bay, Victoria, was essentially a monument to Canada’s racist immigration detention practices. It will not be missed. However, in its place, and within the remains of the original perimeter brick-and-iron fence, stands a block of condos — not the Canadian Coast Guard headquarters which borders the opposite side of Dallas Road today.

The book closes with a brief glossary of architectural terms but, alas, no index.

The vertical format of 305 Lost Buildings, like the plain-Jane one-dimensional facades of its pared-down pen-and-ink illustrations, subconsciously hints at its tomb-stone function, while a march through the pages, checking off each structural obituary in turn, recalls the precision-ordered and well-manicured military section of a graveyard rather than a romp through a picturesque assembly of tottering shapes and forms that might indicate that you are among a more common collection of human saints and sinners.

Requiescat in pace to this slice through the architectural mortality of urban Canada.

*

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of BC, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on BC historic and decorative arts. A recent publication, concerning the Modernist architectural heritage of Victoria (1935-1975), Conservation Guidelines for Modernist Architecture in the Victoria Region (2020), is available in a free on-line digital version. Martin currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia and for Government House, Victoria, and he is group-co-ordinator of the UNESCO Victoria World Heritage Project. Editor’s note: Martin Segger has recently reviewed books by Allen Specht, Liz Bryan, Michael Kluckner, Marc Treib, and Daina Augaitis, Allan Collier & Stephanie Rebick for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1586 Touching down in the past”