1467 Background to Bella Coola

Writing the Empire: The McIlwraiths, 1853-1948

by Eva-Marie Kröller

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2021

$110.00 / 9781487507572

Reviewed by Robert Hogg

*

In her story of the McIlwraith family, Scottish immigrants to Australia and Canada, Eva-Marie Kröller illuminates the lives of the members of a nineteenth century middle-class family, albeit one with its peculiarities and eccentricities. Drawing on the voluminous collection of letters, diaries, scrapbooks, business postcards and publications, particularly of the Canadian McIlwraiths, Kröller provides the reader with a forensic, and at times dense, analysis of how empires are made. Are empires made by grand plans formulated by big historical actors – metropolitan politicians, generals, military conquests and businessmen – or are they made by transported convicts, working-class and middle-class immigrants, and amateur scientists? In Kröller’s analysis it is the ordinary immigrant, going about making a new life for him/herself, establishing and maintaining social networks, who provides the stuff of empires.

In her story of the McIlwraith family, Scottish immigrants to Australia and Canada, Eva-Marie Kröller illuminates the lives of the members of a nineteenth century middle-class family, albeit one with its peculiarities and eccentricities. Drawing on the voluminous collection of letters, diaries, scrapbooks, business postcards and publications, particularly of the Canadian McIlwraiths, Kröller provides the reader with a forensic, and at times dense, analysis of how empires are made. Are empires made by grand plans formulated by big historical actors – metropolitan politicians, generals, military conquests and businessmen – or are they made by transported convicts, working-class and middle-class immigrants, and amateur scientists? In Kröller’s analysis it is the ordinary immigrant, going about making a new life for him/herself, establishing and maintaining social networks, who provides the stuff of empires.

Kröller is Professor Emerita at the University of British Columbia and specialises in comparative Canadian and European literature, in particular travel writing, life writing, literary history and cultural semiotics. Among her other works are The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (2004) and the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (with Coral Ann Howells, 2009).

The McIlwraiths have their origins in Ayrshire, Scotland, where John McIlwraith and Janet Howat, progenitors of the Australian McIlwraiths, married and had twelve children. John was a plumber and town councillor. It is doubtful that, bearing twelve children, Janet had much time for anything else. Nor did her sister-in-law Jean, wife of John’s brother Thomas, a weaver, who together had ten children. The fertility rate, the average number of children a woman has in their reproductive years, in the United Kingdom in 1830 was five, so Janet and Jean were exceptional in this regard. The 1840s and 1850s were years of harsh economic depression in Scotland and this, combined with the need to ease the economic pressure a large family entailed, no doubt contributed to the decisions of Thomas (son of John), and Thomas (son of Thomas the elder), to emigrate to Australia and Canada respectively. The McIlwraith tradition of naming sons either Thomas or Andrew makes a necessity of the genealogical table in the appendix, and even then it is difficult to keep track.

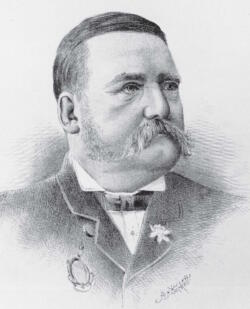

While Writing the Empire embraces ninety members, spouses and associates of the McIllwraith family, Kröller sensibly focuses on four of the most prominent, starting with Sir Thomas McIllwraith, thrice Premier of the colony of Queensland, Australia and fourth child of John and Janet. Sir Thomas’s political career and personal life was nothing if not tumultuous. His first wife, Margaret Whannel bore four children, but was sadly an alcoholic and Thomas sent her to Scotland. He tried to deprive her of her children, but his father objected because Margaret had been on her best behaviour. She died at Maxwelltown, Dumfriesshire on 14 October 1877. Sir Thomas also fathered an illegitimate child in Victoria. He remarried in 1879 to Harriet Ann Mosman and together they had a daughter.

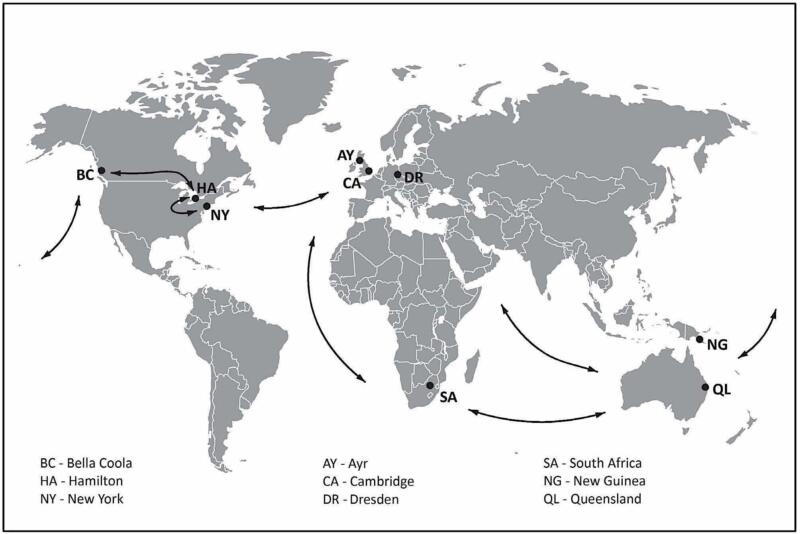

Politically, Sir Thomas (with a background in civil engineering) was a passionate advocate for the expansion of railways in Queensland but seemed always to be able to antagonise a considerable part of the electorate. He was involved in various loan raising and land grant schemes, and as a director of the Queensland National Bank used its resources to fund land speculations. When the bank collapsed a committee of enquiry found a degree of mismanagement that verged on corruption. In 1883 he tried to annex New Guinea for Queensland but an outraged colonial office in London put paid to this grandiose scheme. Kröller states that the connection between the Australian McIllwraiths and their Canadian cousins was tenuous, the most important link being between Sir Thomas’s brother-in-law William in Rockhampton, Queensland, to William’s brother Thomas, in Hamilton Ontario. It is to the Hamilton McIllwraiths that the bulk of Writing the Empire is devoted.

Much of the chapter on the Ontario McIllwraiths is given to Thomas McIllwraith, son of Thomas the weaver and his wife Jean. Both Thomas and his brother Andrew migrated to Canada within a few years of each other. Both became reasonably successful businessmen, diligent in maintaining networks of family, friends and business associates, using correspondence to grease the cogs of colonial advancement. Andrew was a pattern maker and draughtsman in Sarnia. Thomas worked in the Hamilton Gas Light Company and later became a partner in a commercial wharf and a coal transport business. They cultivated a wide circle of friends in the province, including a number of prominent people. Considerable space is given to Thomas’s love of birds, and he became the most well-known ornithologist in Canada, and a co-founder of the American Ornithologists’ Union. In 1886 he published The Birds of Ontario, a landmark compendium of 302 species within the city limits of Hamilton.

One of Thomas’s daughters, Jean Newton McIllwraith, gained a reputation as a writer in Canada, Britain and the United States, although success in the latter was handicapped by allegiance to the British Empire and her criticism of American republicanism. She travelled widely in Britain, Europe and across the United States. Her novels were heavily autobiographical and included The Span O’Life and A Diana of Quebec, as well as a children’s book The Little Admiral. She published extensively in the Canadian, American and British periodicals of the day, and worked as a reader for Doubleday Page in New York.

*

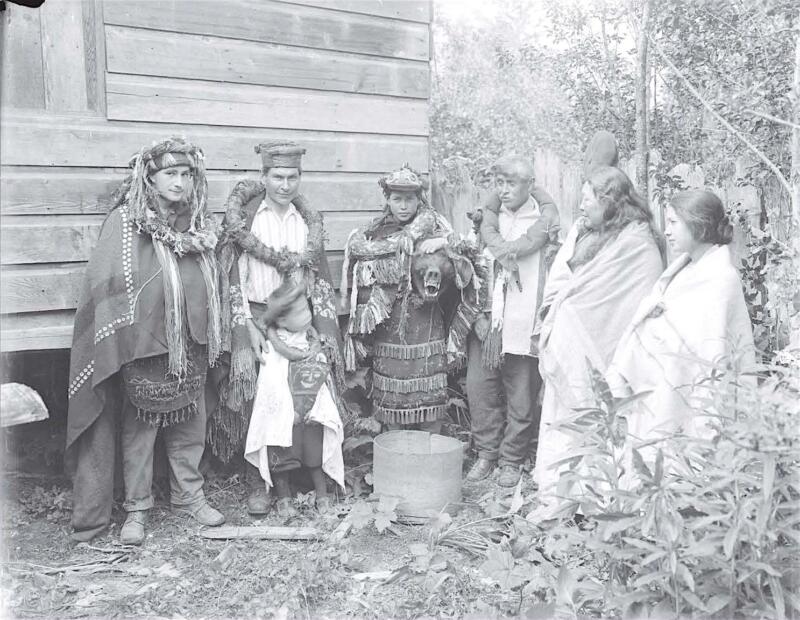

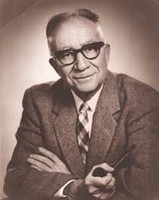

A significant part of Writing the Empire is devoted to the grandson of Thomas the ornithologist: T.F McIllwraith (1899-1964). As a member of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War, T.F. produced voluminous correspondence, including one letter which ran to fifty-four pages. He was very much an empire loyalist, and most of his wartime experiences and interactions were perceived through and moulded by his imperial identity, and his imperial identity reinforced by those same forces. His exposure to non-white British subjects broadened his understanding of the Empire. However, he took for granted the superiority of whites over non-whites and it wasn’t until his work as an anthropologist with first nations people that his thinking changed.

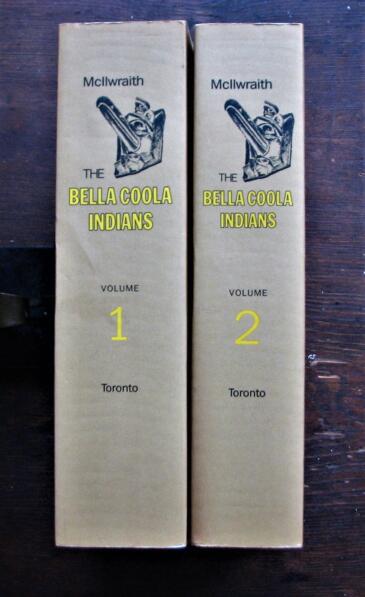

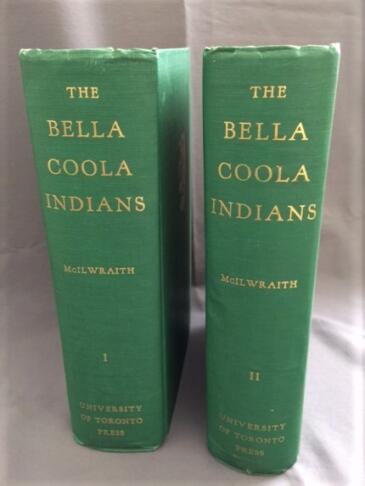

After the war T.F. graduated from McGill University and Cambridge and embarked on a career as an anthropologist. At Cambridge he developed very close relationships with a number of prominent academics including W.H.R. Rivers and A.C. Haddon, both notable for their fieldwork in the Torres Strait Islands. T.F himself had considerable success with the publication of The North American Indian Today (1939) and The Bella Coola Indians (1948). His anthropological work transformed his understanding of empire and his place in it, as well as giving him a profound appreciation of and respect for indigenous peoples.

Kröller has undertaken more research for this work than most historians would do in a lifetime. Her bibliography runs to forty-five pages and it has all been poured into her text. This is both a strength and a weakness. Digressions to a girls’ school in Dresden and biographies of T.F. McIllwraith’s Cambridge mentors require persistence on the part of the reader. However, Kröller is nothing if not thorough and micro-historians and those interested in life writing may well find this text engrossing.

Writing the Empire is a significant piece of scholarship and historians interested in empire and colonialism will benefit from engaging with it.

*

Dr. Robert Hogg has taught history at a number of Australian universities, primarily at the University of Queensland. He is the author of Men and Manliness on the Frontier: Queensland and British Columbia in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). He is currently researching Australian and Canadian soldiers on the Western Front. Editor’s note: Robert Hogg has also reviewed books by Jean Barman, Laura Ishiguro, and Christopher Herbert for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster