Mourning rites in Ancient China

ESSAY: Mourning and Burial Rites in Ancient China: A Grief Process

by Dorothy Dittrich

*

Death is part of life, as are the feelings of grief, sorrow and anxiety that follow the loss of a loved one. While coming to terms with death and coping with loss may be part of living, the feelings that accompany death and loss are among the most difficult we will face, and help to create one of the most perilous passages we will undertake.

In times of grief, an individual may feel so overcome that a sense of displacement and internal dislocation may occur. Even with comfort and support, the one grieving may feel disoriented both internally and externally. What has been real no longer exists. This loss of inner and outer connection can cause a total shattering and in the wake of such a shattering, feelings of futility and meaninglessness may arise causing the individual to withdraw from life. In more epic language, the dead can continue to lay claim to the living.

Fully embracing and experiencing grief can be the means through which an individual comes to terms with loss and returns to life in a fuller more meaningful way. But how is that done? How are such overwhelming feelings to be embraced and experienced?

Here I discuss how ancient Chinese burial and mourning rites served as a means to process grieving, and how the rituals and rites acted as containers in which grief could be placed, felt, experienced, processed and released.

While grief may have the power to be destructive, it also has the power to transform. Using modern psychological explanations of the grief experience, I will discuss how the ancient rites helped mourners work with grief to cultivate the self and move beyond feelings of despair, overwhelm and clinging to ultimately reach acceptance, healing and transformation.

Because I will be using modern psychological definitions of grief that arise from a Western perspective, I will also comment on Western perspectives of ritual and examine some of the differences in grief processing as seen in the past and present, East and West, and both with and without rites.

To Begin

The ability to move through loss may depend not only on one’s capacity to experience grief and mourning, but also on having a process or structure to work through those feelings. If we do not know how to grieve, if we do not have an understanding of what is happening to us, it is possible to become stuck or lost either psychologically or emotionally. Danger lurks in these perilous waters. The feelings that accompany grief are heavy, painful and exhausting, and if the loss is deep, cannot always be managed alone. Loss as a result of death can be the most difficult loss to cope with, perhaps because one is forced to not only come to terms with the loss itself but also with one’s thoughts and beliefs about death. Successfully navigating these emotional and psychological passages requires care and process, both of which are evident in ancient China’s mourning and burial rites.

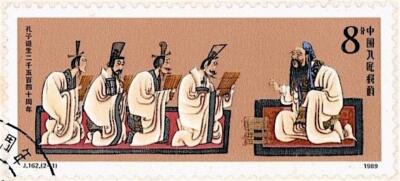

In the time of Confucius

How we view death may impact how we grieve. In Confucius’s time, birth and death were considered natural and necessary parts of a full and well-lived life. The dominant belief was that death was a returning whereby the dead returned to a world separate and different from the world of the living. When a person died, the body became “a corpse and the consciousness turn[ed] into a soul and spirit,” Biao Chen wrote in “Coping With Death and Loss: Confucian Perspectives and the Use of Rituals” (p. 1039). The corpse was buried and transformed into soil while the consciousness (spirit or soul) returned to the world as a spirit or ghost.

Confucius focused his time, energy and teaching almost entirely on the process of living. We do not know his views regarding death or an afterlife because when asked to comment on death, the spirits, ghosts, ancestors or the afterlife, Confucius answered by speaking to the importance of living. In the Analects 11.12, Confucius’s student Zilu asked how to serve the spirits and gods. The Master replied, “Not yet being able to serve other people, how would you be able to serve the spirits.” Zilu said, “May I ask about death?” The Master replied, “Not yet understanding life, how could you understand death?” (Ames and Rosemont, 11:12).

Biao Chen informs us that “Confucianism teaches to attach importance to life and not to be afraid of death … to place one’s hope on the continuation of families…. Although individuals die, they can let their offspring take their place, and thus they can go on living …” (Chen, p. 1042).

In her paper “The Consummation of Sorrow: An Analysis of Confucius’ Grief for Yan Hui,” Amy Olberding writes that “Confucius, like many philosophers, recognized that reconciliation to death, broadly conceived, is necessary if one is to live without the disabling burdens of fear and anxiety. He acknowledged that the fact of human mortality cannot be denied and that an inability to accept this most basic reality imperils the quality of life we can achieve” (p. 279). Confucius did not dwell on the unknowable — life and how to live it was what mattered most. Perhaps this philosophical anchoring, this rootedness in life and the living was helpful in the process of grief in ancient China.

Although Confucius stressed keeping our attention on life and in the here and now, he did not suggest that we ignore our feelings when faced with death and loss. Confucius taught that we realize our humanity through our feelings, and he encouraged the full expression of emotion. It is our feelings and our reactions to the situations we encounter in life that tell us who we are and what we need to learn. Feelings are especially difficult in the case of grief, yet Confucius regarded grief as “a constituent of a flourishing life” (Olberding, p. 280). For Confucius, “the capacity to grieve, to be undone by loss, is in some ways, a measure of our having lived well and richly” (Olberding, p. 280).

It is of no small significance that Confucius’s views on emotion as an agent of change and inner transformation is situated alongside that of twentieth century psychologists and thinkers. The full ownership, investigation and expression of emotions as not only the path, but the compass to self-actualization is key in the fields of psychology and psychoanalysis. Death, loss and the handling of grief are among the greatest challenges to living, and when fully experienced, offer great potential for growth and self-transformation. The challenge is universal and in grief, humanity is joined in a timeless continuum.

Grief

In order to understand how rites might contain and help process grief, it may be helpful to seek a deeper understanding of grief. What is grief and what are we experiencing when we are in it? For Freud, grief presents a complex process that contains psychological dimensions. In his essay “On Transience,” Freud explains his basic theory of mourning:

Mourning over the loss of something that we have loved or admired seems so natural to the layman that he regards it as self-evident. But to psychologists mourning is a great riddle — We possess, as it seems, a certain amount of capacity for love — what we call libido — which in the earliest stages of development is directed towards our own ego. Later, this libido is diverted from the ego on to objects, which are thus in a sense taken into our ego. If the objects are destroyed or if they are lost to us, our capacity for love (our libido) is once more liberated; and it can then either take other objects instead or can temporarily return to the ego. But why it is that this detachment of libido from its objects should be such a painful process is a mystery to us and we have not hitherto been able to frame any hypothesis to account for it. We only see that libido clings to its objects and will not renounce those that are lost even when a substitute lies ready to hand. Such then is mourning.

At the point of loss, grief seems to “empty us out, deplete us” Joan Berzoff writes in “The Transformative Nature of Grief.” One can feel exhausted in part because in Freud’s view, the mourner withdraws from the world and focuses primarily on the object of loss. Freud called this process hypercathexis, which refers to “the intense energy with which we connect to the person who has died” (p. 263). At this point the person who is grieving enters a kind of limbo or no man’s land of neither the living nor the dead. “Caught between holding onto and letting go of the object of his/her loss,” the mourner becomes “preoccupied with the memories of the person who has died” (p. 263). A feeling of a loss of reality can accompany this stage of mourning. The one left behind may try to keep the dead close by telling stories, focusing on memories, photos, even wearing the deceased’s clothes. Jungian analyst Marie Louise Von Franz writes that it is common for widows and/widowers to find themselves participating in the hobbies and tasks of the deceased partner even though they may have held no interest in these activities while the partner was alive. The mourner may also start to eat the favourite foods of those who have died and even have conversations with the departed. These often unconscious actions are attempts to maintain a relationship with the dead.

Freud’s theory of mourning suggests that the mourner’s task is to decathect, or slowly withdraw energy from the one who has died and reclaim it for oneself. In “Mourning and Melancholia” Freud argues that “time is needed for the command of reality-testing to be carried out in detail, and when this work has been accomplished the ego will have succeeded in freeing its libido from the lost object” (p. 251). “If all goes well, the mourning period ends with the individual accepting the reality of the loss and continuing the connection through memory and moving back into life.” The process complete, the griever’s energy would be available to love again.

But grief is a complicated emotion with many difficult and complex layers that can derail the process. In “Mourning and Melancholia,” Freud suggests that while a full experience of grief can lead to a deeper understanding of oneself and the world, mourning can lead to a state of melancholy if unresolved or incompletely processed. Freud describes melancholy as an emotional state in which grief over the loss of the love object has been internalized as rejection. The interpretation of loss as rejection or being left may cause feelings of unconscious self-hatred resulting in depression and chronic grief. As Freud defines it, “In mourning it is the world which has become poor and empty; in melancholia it is the ego itself” (p. 245).

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s grief process, more commonly known as the five stages of grief, is another theory of mourning that entered mainstream psychology in the latter part of the twentieth century. Kübler-Ross introduced this model of grieving in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying. Kubler-Ross describes the fives stages of grief as denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. According to Kubler-Ross, the five stages do not necessarily occur in order, nor is there a time limit for how long each stage may take. Nevertheless, the first stage is almost always denial. Denial of the reality of the situation seems to be a universal response and perhaps the best immediate defence against shock.

A mourner can become trapped between stages in a kind of back-and-forth dance such as from denial to bargaining to denial again, or from anger to depression and back. Becoming stuck in one or another stage or turning grief inward on oneself are examples of becoming lost and needing some means of finding a way through the process.

While Freud, Kubler-Ross and many other psychological theorists have provided explanations for what is being experienced in grief, they have not provided specific steps or a method to move through the feelings. We may know what is happening and why, we may even know where we are emotionally — denial, anger, bargaining, in a state of hypercathexis or withdrawal — but that does not mean we know how to be with our feelings of grief. We may be clear where we are on the map, but still be lost. In the twenty-first century, forms of therapy or treatment are used to provide a process and a sense of direction for those grieving. Could the death and mourning rites have fulfilled such a function in ancient China? Did the rites provide a psychological process of healing? Perhaps by following the rites, the mourner was able to take the necessary steps to walk through and complete Kubler-Ross’s stages of grief.

“The meaning of Ritual is deep indeed” (Watson, p. 94).

Time and space for processing is elemental to healing. In “Contemporary Rituals and The Confucian Tradition,” Howard Curzer writes that “Rituals force us to pause in the midst of our activities. A check that temporarily prevents us from pressing forward aggressively with our own, often self-centered projects allows us the opportunity to reconsider….” and “rituals provide individuals with a sense of rootedness” (p. 293). This rootedness may be a key aspect of the rites and rituals as a process of healing. In times of loss, our sense of rootedness to place, to people and even to ourselves may feel completely absent. We may feel adrift or abandoned. In these times, the rites become the ground to stand on.

Ritual acknowledges the depth of loss and acknowledgement is vital to beginning a healthy grieving process. Acknowledgement grounds us in truth and offsets denial. Ritual may also give permission to emotionally and psychologically take the time that is needed to grieve.

There seems to be an unspoken expectation in Western culture to get back to work Monday morning after a catastrophic loss. Perhaps it is no wonder the culture appears to be suffering from depression, anxiety and addiction — all possible by-products of grief unexpressed, unprocessed or blocked. It takes time, patience and energy to experience and be with loss, to take in, grieve, and create meaning from loss.

Survival dictates that we continue, that we go back to work, keep moving and stay with the living. How and when we do that is the issue. Numbing, suppressing or repressing feelings in order to continue on with life may be a form of transformation, however the transformation is one of deadening rather than opening to a richer experience of life. Regardless of the reason for avoiding difficult feelings, refusal of emotions is ultimately harmful to psychological and physical health even though in the moment, avoidant behaviour may feel effective.

Although the perception, particularly in the West, may be that ritual somehow inhibits or even eradicates authentic feeling, and that following a specific set of rules is a false or synthetic process, for Confucius and Hsun Tzu and their followers, that is not at all the case. In following rites, one can find freedom to fully express feelings and thus become more fully human. This transformation can occur in individuals, communities and nations.

In contrast with the East, the West in its evolution as a culture has rebelled against, if not actively rejected, formal ritual and/or tradition whether religious or secular. Curzer speaks to this following his research into the thinking of western ethicists on the subject of ritual. Although “Rituals … are absolutely central to, and esteemed by, the Confucian tradition,” they seem to be absent in any discussion in the West. “Contemporary Western ethicists do talk about habits, practices, and ceremonies, but while these are related to rituals in complex ways, they are not rituals. Overall, Western ethicists are simply ignoring rituals!” (p. 290) This is not meant to criticize the West, however, in the absence of rituals that contain time and guidance, the West may be experiencing an empty space where healing processes and structures could exist to hold, assist and potentially comfort the bereft.

Western culture seems to have very little in place for assisting in grief and loss. If the loss is sudden or especially traumatic, the need for joining with others to mourn and share in the loss may be acute. Feelings of the loss of reality, connection to place, people, and context can be true not only for the individual, but also for communities and even nations. Rituals can provide the structure and the means through which to gather and grieve.

In “Mourning and Meaning,” Robert Neiymeyer discusses “integration and regulation” (p. 236) as a process that holds societies together during times of upheaval: “Cultural rituals serve both integrative and regulatory goals by providing a structure for the emotional chaos of grief, conferring a symbolic order on events, and facilitating the construction of shared meanings among members of the family, community, or nation” (p. 236). This construction is part of a process of healing on a large scale.

Generally speaking, the Western approach tends to psychologize grief. In keeping with an emphasis on the individual, counselling or psychotherapy are used to assist in healing. Grief is treated, rather than played out or enacted in ritual within a larger group context. This is not a bad thing per se, however it does limit the visibility of the one grieving. As Curzer states, rituals provide “bonding experiences and shared practices among groups of various sizes ranging from pairs to nations. Because they are shared, [rituals] make us feel as if we belong to a community” (p. 295). This feeling of belonging and being seen, is extremely important to help counter feelings of isolation and aloneness that often accompany grief and loss. Through performing rituals, we discover, display, and reinforce the social components of our selves. “Rituals also aid us in expressing our non-social components. They provide boundary constraints within which we may express our individuality safely. Moreover, rituals guide the expression of desires and passions, particularly in stressful situations” (p. 294).

The play’s the thing

A final aspect of ritual that is important to mention is its close relationship to theatre. Both are forms of storytelling, both are scripted, have costumes, sets and props, and both can be powerful agents of healing and transformation. With theatre, an audience watches a story acted out on stage. Though it is not a real event, the audience nonetheless may experience real emotions. Through the emotions evoked by the play, the audience has the opportunity to experience their own healing. The fact that it is only a play creates safety for the audience to experience deep feelings which may be felt and released as cathartic experience. This powerful experience of catharsis is possible because the story is also being told to both the conscious and unconscious minds. The Greek tragedies in particular were extremely effective in creating catharsis as they spoke deeply to unresolved or unexpressed feelings of violence, love, betrayal and, of course, grief stored as unconscious content in the minds of members of the audience.

Ritual may provide similar experiences of catharsis, but unlike theatre where audience and actor are separate, in ritual, everyone is part of the enactment. Rites provide the script through which participants express their grief and through performance of the rites, healing and release is possible. Playing a role in ritual may provide a kind of safety that allows the participants to fully immerse in the emotion without becoming overwhelmed. Space is created by the rites to allow the participants to be with their feelings without the danger of feeling overwhelmed.

“Ritual begins in that which must be released, reaches full development in giving proper form, and finishes in providing it satisfaction.”

So how do the rites act as a process for healing and transformation? Hsun Tzu tells us that the purpose of the rites is “to provide the means to express grief.” Simply put, in order to be healthy, one has to feel and release grief. Blocked feelings block energy which blocks health physically, emotionally, spiritually and psychologically.

An interesting joining of psychology and physical health can be found in the study of anxiety. In the psychological community, the word ritual is used as a technical term to describe a repetitive behaviour systematically used by a person to manage or prevent anxiety. This is a meaningful definition in terms of viewing the rites as a psychological process. Ritual as a form of anxiety management may in fact be core to the concept of the rites as a healing process. Anxiety is destructive. It blocks and inhibits the flow of emotion, which in turn blocks energy and health. One cannot be blocked by anxiety if one is to fully vent one’s grief. Seemingly superficial questions such as what to do and when, what to wear, eat, and how to act can create tremendous feelings of anxiety in times of crisis. These questions can suddenly take on energy and substance that they may not ordinarily possess, causing extraordinary and perhaps undue stress to people already suffering. While answers to those questions may not eliminate the pain and suffering caused by loss, they can lessen anxiety allowing the natural grief experience to flow in a safe and useful way. As Howard Curzer explains,

Rituals structure novel and/or stressful and/or complex situations, enabling people to move smoothly and easily through those situations. Moreover, by removing the need for working out what to do, rituals streamline various processes even in ordinary situations (p. 293).

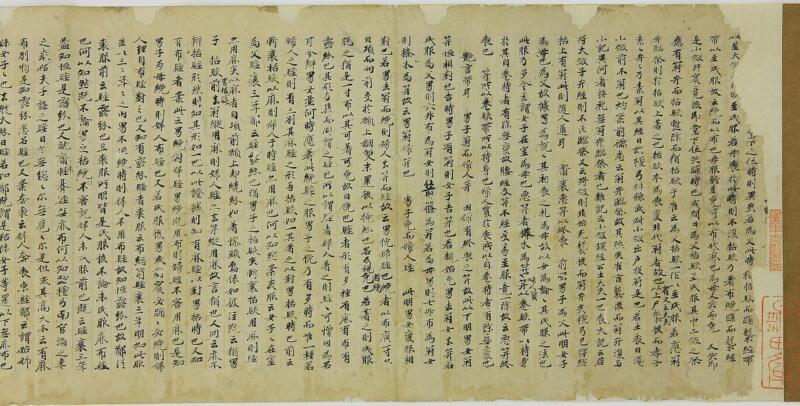

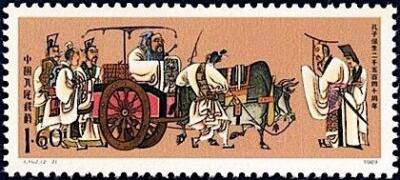

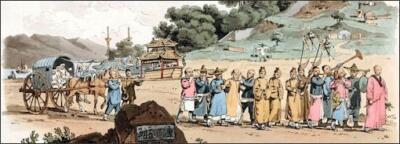

The rites for mourning and burial are laid out in explicit detail, beginning with the moment of death and ending with acceptance and letting go. Every situation that might arise is addressed, every question, answered. Regardless of the relationship — intimate, professional or familial — the rites provide a template for those experiencing loss and mourning to act within. Details that include how and when to send the announcement of the death, to how to respond, when to travel, what to wear, how to behave when one arrives at the place of the dead and how long to grieve are all described in the Li Ki, also known as The Book of Rites, a collection of texts that describe in detail the rites and rituals, rules and ceremonies that were used in a variety of social contexts. Written during the late Warring States (5th century – 221 BCE) and former Han periods (206 BCE – 8 CE) the Li Ki is one of the Five Classics of Chinese Confusion literature.

Here are some brief examples of the details on mourning from “The Rules on Hurrying To Mourning Rites,” Book XXXI of the Li Ki: When one received the news “he wailed as he answered the messenger and gave full vent to his sorrow.” He travelled 100 li a day, but “only when the rites were for a father or mother did he travel while he could yet see the stars.” While travelling, he “avoided wailing in the market place and looked toward the frontier of his own state when he wailed.” In keeping with the rites, when he arrived, he knelt on the east of the coffin with his face to the west and wailed.

Because the rites are so enormously detailed, I will use only a few examples to further explore my thesis. In “A Discussion of the Rites” the ancient Chinese philosopher Hsun Tzu describes the moment of death and a typical response as though he is speaking to us today. The denial and disavowal — responses Kubler-Ross and Freud describe — were clearly part of the emotional landscape in ancient China:

When the silk floss is held up to the dead man’s nose to make certain that he is no longer breathing, then the loyal subject or the filial son realizes that his lord or parent is very sick indeed, and yet he cannot bring himself to order the articles needed for laying in the coffin or the dressing of the corpse. Weeping and trembling, he still cannot stop hoping that the dead will somehow come back to life; he has not yet ceased to treat the dead man as living (p. 98).

After addressing the first moment on the realization of death, Hsun Tzu lays out how the mourner is to proceed. The instructions follow in this way: Time is given to the mourner to become resigned to the fact that the loved one is dead. Only then can he move forward “therefore, two days will elapse before the dead can be laid in the coffin, and three days before the family will don mourning clothes” (p. 99). Next people are notified of the death. “The period the dead can lie in state should not exceed seventy days nor be less than fifty” (p. 99). This period provides time for the news to get to those who live far away and to give those people time to travel. It also provides time to prepare for the funeral and clear up the personal or business affairs of the dead:

The three months preparation for burial symbolizes that one wishes to provide for the dead as one would for the living and to give the dead the proper accoutrements. It is not that one detains the dead and keeps him from his grave… to satisfy the longings of the living. It is a token of the highest honour and thoughtfulness (p. 99).

Though time is being allotted for preparation, time and space is also provided for the mourners to process the initial loss and work through denial, the first stage of grief. This is a clear example of form, or rites, containing the grief process. The rites allow room to explore and be with the loss. They also give the mourner permission to be still and with his or her grief. The impulse to get back to work in order to avoid fully feeling the loss is not possible because it is not part of the rites. In ancient China, it would have been unthinkable to be so disrespectful to the dead. Anxiety around facing deep feelings may surface, but this is expected and provided for in the form. There is no choice but to stay in the process and be with the feelings. At no point is anyone encouraged to get on with it or get back to work even if in some ways getting back to work might be preferred.

Hsun Tzu tells us repeatedly that the rites’ detailed instruction “is all done in order to emphasize the feelings of grief” and “to provide the means to express grief.” Confucians in ancient China used the rites to both control and reveal “naturally” their feelings of sadness. In the Li Ki, the instruction is for the mourner “to wail and (give) full vent to sorrow.” In order to experience intense feelings and to release, safety is needed. The rites provided safety by providing strict rules. While rules may often be seen as confining, rules can also be freeing. It can be argued that only when one feels safe can one let go.

In Confucian times, it was thought that the dead were simply going on a journey and that it was the responsibility and duty of the living to help them with this journey. Life and death were regarded as an integral whole not belonging to the individual, but as a part of “the stream of all of life.” Death was regarded as a form of birth — the end of life as we know it, but the birth of something else. According to Hsun Tzu:

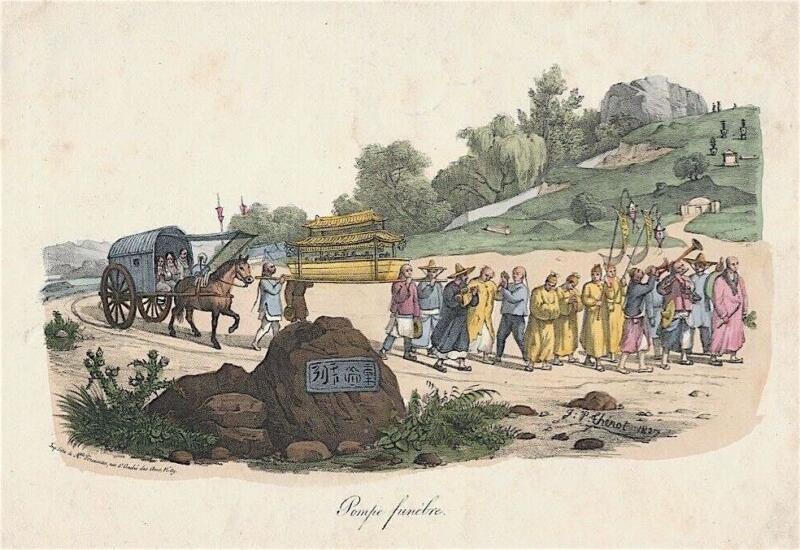

The funeral rites have no other purpose than this: To make clear the principle of life and death and to send the dead away with grief and reverence and to lay him at last in the ground. To bury the dead in the same way one would send off the living and to make sure both the living and the dead, the beginning and the end are attended to – this is the rule of ritual principle and the teaching of the Confucian School (p. 105).

In the funeral rites “the dead are treated as though dead and yet as though still alive, as though gone, and yet as though still present. Beginning and end are thereby unified” (p. 103). This blurring of the lines between life and death is played out in the rites in symbolic and literal ways. Is it possible that this unity holding two states provided psychological space for a time of transition allowing the survivors to move through one or more of the stages of grief?

When a person dies, the hair and body are washed, food is placed in the mouth, the ears closed with silk floss, raw rice is put in the mouth and the mouth stopped with dried cowry shell. The body is dressed in underwear and three layers of outer garments, a sash but no sash buckle, the hair is arranged, but no hat is added. The name of the deceased is put on a wooden tablet so the coffin will not be lacking a name. Articles added to the coffin are incomplete. Jars and wine flagons are empty, carvings and pottery are incomplete, instruments are strung but not tuned, reeds and pipes are not sounded. A carriage is buried but the horses are taken home to show that the carriage will not be used. Token personal items belonging to the dead are “taken to the grave with him symbolizing that he has changed his dwelling” (p. 104). The dead person is treated in a way that indicates he has merely changed where he lives, yet it is made clear he will never use these items.

A subtle and powerful detail in the first phase of the rites comes when the body is moved to the coffin. It is not only the change of place, but also in the change of language referring to the dead that is striking. This passage from the Li Ki Book XXXII, illustrates the point: “2. On the third day there was the (slighter) dressing (of the corpse). While the body was on the couch it was called the corpse; when it was put into the coffin, it was called kiû.”

Here the body is given a new name. This moment creates a shift, separating the living and the dead. The body on the couch may have been part of this world but once in the coffin it becomes part of the next. This tiny shift introduces a next step in the process:

At the moving of the corpse, and lifting up of the coffin, (the son) wailed and leaped, times without number. Such was the bitterness of his heart, and the pain of his thoughts, so did his grief and sorrow fill his mind and agitate his spirit, that he bared his arms and leaped, seeking by the movement of his limbs to obtain some comfort to his heart and relief to his spirit.

And Book XXXII continues:

The women could not bare their arms, and therefore they (merely) pushed out the breast, and smote upon their hearts, moving their feet with a sliding, hopping motion, and with a constant, heavy sound, like the crumbling away of a wall. The expression of grief, sorrow, and deep-seated pain was extreme; hence it is said, ‘With beating of the breast and movement of the feet, did they sorrowfully accompany the body; so they escorted it away.’ When (the mourners) went, accompanying the coffin (to the grave), they looked forward, with an expression of eagerness, as if they were following some one, and unable to get up to him. When returning to wail, they looked disconcerted, as if they were seeking some one whom they could not find. Hence, when escorting (the coffin), they appeared full of affectionate desire; when returning, they appeared full of perplexity. They had sought the (deceased), and could not find him; they entered the gate, and did not see him; they went up to the hall, and still did not see him; they entered his chamber, and still did not see him; he was gone; he was dead; they should see him again nevermore. Therefore they wailed, wept, beat their breasts, and leaped, giving full vent to their sorrow, before they ceased. Their minds were disappointed, pained, fluttered, and indignant. They could do nothing more with their wills; they could do nothing but continue sad (Li Ki, Book XXXII).

The ritual enactment of leave-taking speaks powerfully to the unconscious and provides satisfaction to deeper levels of uncertainty and fear. Those participating in the rites are working with and in the act of simultaneously allowing the deceased to move on while allowing themselves to let the dead person go. The line “they could do nothing more with their wills: they could do nothing but continue sad,” is poetic instruction in surrender, acceptance and letting go. No act of will can bring the dead back, no bargaining — another stage of grief — can change what is. There is nothing to be done but feel sorrow and mourn.

In another sense, this ritual enactment could help to avoid the melancholia Freud spoke of. Feelings of rejection and/or abandonment, a sense of being left, may be alleviated by empowering the person experiencing loss, through participation in the preparation of the body and delivering the dead to his or her new dwelling. The mourner would be working symbolically at a deep emotional and psychological level using the rules of the mourning rites to provide a path through the stages of denial (and disavowal), perhaps even bargaining or anger. At a conscious and unconscious level checks and balances are being played out. The symbolic language of ritual is speaking to a part of the psyche that words do not access and may provide deeper comfort and healing than verbal communication ever could.

In loss, feelings of loose ends and helplessness can block feelings of closure. Escorting the body to the new dwelling place tells a story of care and completion that may signal closure to the unconscious. While these enactments also allow time for the new reality to sink in, they are illustrating through metaphor the stark reality that the deceased has moved on. Through participation in that move, a feeling of purpose and involvement may enter the process helping to alleviate feelings of victimization or helplessness. Gathering together in support and healing has been discussed. However, the Li Ki also includes instructions in the event that one could not attend:

14. When one heard of the mourning rites, and it was impossible (in his circumstances) to hurry to be present at them, he wailed and gave full vent to his grief. He then asked the particulars, and (on hearing them) wailed again, and gave full vent to his grief. He then made a place (for his mourning) where he was, tied up his hair, bared his arms, and went through the leaping (Book XXXI).

In this way, the mourner could participate along with family and friends with the rites helping to facilitate feelings of connection and inclusion despite physical distance. Because grief can feel isolating, this kind of connecting could have provided a feeling of safety to be alone with deep and intense feelings. This is a very significant issue as it illustrates the power of the rites to act as a container beyond the boundaries of proximity. Here the rites themselves transcend physical place and distance.

Who am I now that you’re gone?

This is a question that accompanies loss. When one dons the mourning garb, one steps into a role, an identity and a place to be. While the meaning of the ritual mourning garb was primarily symbolic — the frayed sackcloth, for example, had “an unpleasant appearance, and served to show outwardly the internal distress” (Li Ki Book XXXIV), the mourning garb was also a costume that signified a role. Having a role to play in the ritual provided validation and affirmation of relationship and identity. It also provided safety. In the case of total overwhelm, the mourning garb creates a slight emotional distance and therefore becomes a place of safety and containment. If a person is shattered, the clothing or costume may become a way of holding the pieces together. One has a part to play in the ritual and a costume to wear. Clothing becomes part of the grief process through the rites. Those grieving may have felt reassured at an unconscious level by wearing the prescribed attire. Ritual clothing not only telegraphs the mourner’s respect and reverence for the dead, it may also serve the mourner by connecting and affirming relationship to the dead. This affirmation and connection could help maintain a sense of identity and continuity in the face of loss and the initial internal chaos that goes with it.

Time heals all wounds

An extraordinary element to the mourning and burial rites is the aspect of time. The amount of time needed for each aspect of the process is allotted with generosity. Perhaps this is because time is such an enormous component in healing. To quote Hsun Tzu, “When a wound is deep it takes many days to heal. Where there is great pain, the recovery is slow.” An example is the spacious allotment of time for the body to lie in state. As discussed earlier, much time is spent on the practical — but does a psychological process of letting go and healing occur? As with the preparation of the body and escorting it to its new dwelling place, a story is being played out between the living and the dead involving time and transformation both physically and symbolically.

Hsun Tzu writes that during the three-month period, “it is the custom…to keep changing and adorning the appearance of the dead person, to keep moving it farther and farther away and as time passes to return gradually to one’s regular way of life” (p. 100). To be direct, the dead are being adorned to hide the decomposition of the body and are most likely being moved away because of the smell. “If they (the dead) are not adorned they become ugly then one will feel no grief for them. Similarly, if they are kept too close by one becomes contemptuous of their presence” (p. 100).

Primitive though this practice may seem to our sanitized sensibilities, one wonders if this immediate experience with the biological reality of death is not an effective and honest way to achieve letting go. This aspect of the rites is rich in symbolism and theatricality. With the once adored becoming daily an assault to the senses, the wished-for return of the loved one is now replaced with the desire to let go and allow the body to be buried. This lengthy period of time combined with the visible, measurable reality of death must have helped those grieving to come to a natural phase of acceptance and letting go. Freud’s cathexis is not yet complete, but a certain amount of the work toward the withdrawal of energy sent out to the lost love object would surely have taken place while living with the deceased. This coexistence, the dead and the living inhabiting the same space, may seem to be a temporary blurring of the boundaries between worlds, a powerful image that speaks eloquently to the unity of life and death as part of the same continuum. Might it not also speak to the psyche and the processes of denial, bargaining, grief, anger and acceptance? In Western culture, where typically the body is taken away almost immediately, denial of death may almost seem to be supported by comparison. In the day-to-day living with the dead, certainly denial would be difficult to maintain. Time allowed for grief and reflection and time to find meaning during those three months is an enormous part of the process.

The final aspect of time that the rites deal with is the manner in which time is divided for the period of grieving. Mourning periods are set “on the basis of a year because in that time heaven and earth have completed their changes, the four seasons have run their course and all things in the universe have made a new beginning” (Hsun Tzu, p. 106). Three years is the longest amount of time allotted for mourning and reflects the highest honour given. This period is for parents and rulers (who are parents to the people and so afforded the same respect). Three, five and nine-month periods reflect “the lowest degree of honor” (p. 107).

The three-year mourning period comes to an end with the twenty-fifth month. At that time the grief and pain have not yet come to an end, and one still thinks of the dead with longing, but ritual decrees that the mourning shall end at this point. Is it not because the attendance on the dead must come to an end and the moment has arrived to return to one’s daily life? (Hsun Tzu, p. 106).

Though the period of time allotted for grieving parents and rulers is predicated on the cycle of a year, I cannot help but wonder if the three-year period that the child grieves the parent is a reflection of the three-year period in attachment theory during which the parent carries the child from birth. The cycle of life, birth and death, is completed through a kind of reciprocity with the child once carried, now carrying and processing grief for the parent. My curiosity and wonder about this lens through which to view the meaning of the three-year period is based on attachment theory pioneered by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth.

When the rites dictate the end of the period of mourning, it is not suggested that grief has ended, but that the focus must now change. Using the metaphor of the deep wound, enough healing has occurred that one can return to the world without risk of infection or further wounding.

Grief and Transformation: we work on grief and grief works on us

Intense and powerful feelings such as grief can change or transform the individual either for good or ill, depending on how the individual deals with the experience.

In few other situations are people more vulnerable and exposed in their capacity to feel, respond and manage themselves, than in situations involving death and loss. Grief, loss and mourning have been studied and discussed as experiences that can literally shatter and dissemble the one grieving. Though shattering is painful in the extreme, when our shattered self is brought back together, it is possible that this devastation, this shattering may result in a new person. As Joan Berzoff writes in her essay, “The Transformative Nature of Grief,” “grief changes the individual on an emotional and psychological level. After the experience of being shattered a new person can emerge from the experience.” Berzoff states that “While Freud was the first psychological theorist to write about how grief and loss change the mourner” (p. 263), he is only part of a long line of thinkers, philosophers, artists and searchers who have held a belief in the transformational power of grief.

For Freud and his followers much transformation happens through a process Freud called identification, which has to do with idealizing and/or identifying with the deceased. “In mourning we unconsciously take in aspects of the person whom we have lost,” contends Freud. “These kinds of identifications change who we are, our selves, for better or for worse” (p. 266). Freud tells us that in cases where a relationship has been less than flourishing, the aspects of the person taken in may be shadow — this is negative transformation. Though we tend to think of transformation as positive and even transcendent, for the melancholic who internalizes grief and loss as rejection, transformation is extremely negative. This may not fit the wished-for transformation, but it is nonetheless transformation and cannot be dismissed.

Ironically this exact same process can have positive transformational results if the relationship is one of love and respect, as Joan Berzoff explains:

In the Ego and the Id, Freud wrote about the important function that identification plays in grief; it is through identification with the deceased that aspects of the person who has died come to reside, unconsciously, in the self. Taking in and identifying with aspects of those who have died is what makes mourning bearable and even transformative (p. 263).

Another voice from the psychological field is that of Hans Loewald, who shares a more Confucian view. According to Loewald, though loss is painful, it can also lead to growth and freedom. In his philosophy of loss, Loewald bridges Freud and Confucius, seeing the process of taking in parts of the other into the self as a positive achievement. Here is the opportunity to identify with the values, ideals and conscience of the deceased. In so doing, the content of the mourner’s superego changes, often reshaping the survivor’s values and ideals. Mourning then offers the opportunity to change not only who we are but who we want to become. So while loss is always a deprivation it also provides the potential for gain (p. 266).

The sense that grief provides potential for learning, for growth and transformation is core to the Confucian belief that crisis presents opportunity — the opportunity in grief to expand through embracing difficult feelings. Additionally, Loewald joins Confucian beliefs that the dead carry on through the living. According to Biao Chen in his essay “Coping with Death and Loss,” Confucius and his scholarly followers, especially Tseng-tzu, attach fairly high importance to the mourning ceremony which has a direct relationship to their thinking about the way of inner growth” (p. 1043). And “paying attention to the ceremony of mourning, burying and sacrifice can train people to be kind hearted” (p. 1043). Clearly the rites are aiding in the process of emotional and psychological growth. This belief may have been attached to the belief that sorrow comes from the heart and the activated heart of sadness or the broken heart is the seat of compassion.

To Conclude. Only when nature and conscious activity combine does a true sage emerge (Hsun Tzu, p. 102).

By facing loss, being and working with difficult feelings, we may find healing and growth in our worst experiences. Using the rites as instructions and a means to hold and contain our shattered selves as we sort through the stages of denial, anger, bargaining, grief, acceptance, memory, cathexis, hypercathexis and identification, it is possible to rebuild if not replace the damaged or shattered self that resulted from the loss. This transformation, this birth of a new self, with health and wisdom, a deeper appreciation of life and the capacity for a richer more meaningful existence may be the gift, the hidden treasure gained from loss.

*

Dorothy Dittrich is a playwright, musical director, sound designer and composer. She has been working and playing in the Vancouver Theatre for over twenty years. Her plays include Jessie award-winning The Piano Teacher, an Arts Club Theatre Silver Commission, When the Moon Falls, Two Part Invention, Mouthpiece, Lesser Demons and The Dissociates. Her award winning musical, When We Were Singing has been produced across Canada including the National Arts Centre, and in the U.S., including a workshop and staged sing-through in NYC. She has been writer in residence at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in Toronto. The essay published here, “Mourning and Burial Rites in Ancient China: A Grief Process,” received the Paul Tai Yip Ng Memorial Award for outstanding paper on an aspect of Canada-Asia relations. Ms Dittrich is a graduate of SFU’s Masters of Liberal Arts Program. She lives in East Vancouver where she continues to write and perform music as well as plays and other stories. Editor’s note: Visit Dorothy Dittrich’s website here.

*

References:

Ames, Robert T. and Rosemont, Henry Jr. 1998. The Analects of Confucius: A Philosophical Translation. New York: Ballantine Books.

Berzoff, Joan. 2011. “The Transformative Nature of Grief and Bereavement.” Clinical Social Work Journal 39: 262–269.

Chen, Biao. 2012. “Coping With Death and Loss: Confucian Perspectives and the Use of Rituals” in Pastoral Psychology, Springer Science+Business Media LLC.

Curzer, Howard J. 2012. “Contemporary Rituals and the Confucian Tradition: A Critical Discussion,” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 39:2, 290–309.

Freud, S. “Mourning and Melancholia.” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 56, 237-258.

Freud, S. “On Transience.” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV (1914-1916): On the History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychology and Other Works.

Jones, James W. 2010. “Mourning, Melancholia and Religious Studies: Is the Lost Object Really Lost?” Pastoral Psychology 59.

Neimeyer, Robert A., Prigerson, Holly G. and Davies, Betty. 2002. “Mourning and Meaning.”American Behavioral Scientist 46: 235. http://abs.sagepub.com/content/46/2/235 http://www.sagepublications.com

Olberding, Amy. 2004. “The Consummation of Sorrow: An Analysis of Confucius’ Grief for Yan Hui,” Philosophy East and West 54, no. 3: 279–301.

Tzu, Hsun. 1963. Hsun Tzu Basic Writings, trans. Burton Watson, New York: Columbia University Press.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Mourning rites in Ancient China”

I’ve been asked to post this comment by a friend, Jean, who used to teach in Nanking: “I loved the article on the Chinese approach to death, which does not surprise me at all. They have such reverence for life, and every aspect of life, death, and the afterlife, and I was fortunate to be there several years when the “Day of the Dead, and Sweeping of the Tombs” occurred. Sweeping of the Tombs is when the departed are honoured, and

many gifts are placed on the tombs: food, fake money, flowers, plants, and items they would likely not have had when living – miniature swimming pools, houses, animals etc. etc. The tomb is indeed swept, and many lovely items placed. It is also believed that this is the day when the spirits are closest to the earth, and can communicate with those still living. Thank you so much for sending. It brought many sweet memories back.”

Thank you, Dorothy, for your illuminating research and synthesis of the differences between Eastern and Western approaches to grief and death. I particularly appreciated your exploration of rebuilding identity and self through the transformative power of grief. Your distinctions between negative transformation (when or how grief turns to self-attack) and positive transformation (when one can assume or grow into the positive traits of the dead person who is mourned), is brilliant and innovative, especially valuable for the evolving field of palliative care and the need to have multicultural skills regarding death. The mourning rituals that you describe are fascinating to read about, not to mention hopeful and educational for those who seek a variety of ways to grieve. In reading your work, I learned much more about the stages of grief and the importance of rituals to healing.

Lee Reid