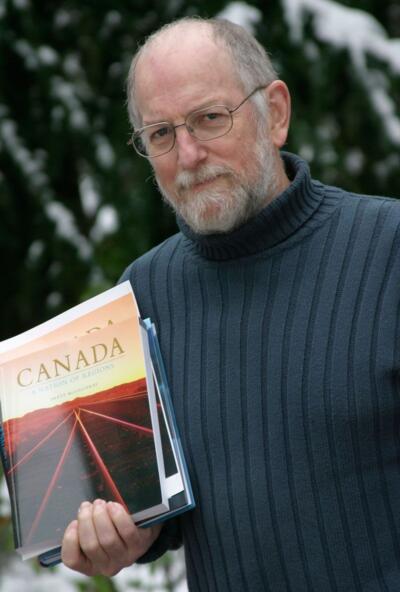

1305 McGillivray’s essential geography

Geography of British Columbia: People and Landscapes in Transition (fourth edition)

by Brett McGillivray

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2020

$55.00 / 9780774864329

Reviewed by Ken Favrholdt

*

Brett McGillivray’s Geography of British Columbia: People and Landscapes in Transition has withstood the test of time since its first edition in 2000, which I reviewed for BC Studies (Winter 2001/02). Time and distance (my sojourn in Alberta) has given me perspective to view BC and this fourth edition (2020) with a more critical eye and knowledgeable background.

Brett McGillivray’s Geography of British Columbia: People and Landscapes in Transition has withstood the test of time since its first edition in 2000, which I reviewed for BC Studies (Winter 2001/02). Time and distance (my sojourn in Alberta) has given me perspective to view BC and this fourth edition (2020) with a more critical eye and knowledgeable background.

Professor emeritus in the Faculty of Geography at Capilano University, McGillivray has recognized the need to update his geography of the province. Like an onion, the book has grown more layers as the evolution continues from one edition to the next. At the heart, of course, is the physical landscape, which remains essentially the same as earlier editions. But even the physical landscape has undergone dramatic changes over time, often human-caused — such as deforestation, hydro development, dyking of watercourses, and as our recent understanding shows, the growing impact of climate change. In his Preface, McGillivray describes the changes from the Third (2011) Edition, most importantly, that “the resource sector of the economy is not nearly as important as it once was.”

There are ten chapters (11 counting the conclusion) divided into two parts.

The first chapter describes the regions of BC, serving as an introduction to the province. These regions are areas that have common physical or human (cultural) characteristics, although the boundaries are more blurred today than in the past. However, people are familiar with the vernacular names such as Okanagan, Cariboo, and Lower Mainland. One might expect this opening chapter to reveal recent changes, but it remains surprisingly constant, as the regional map (figure 1.1) reflects.

Some minor details need attention. As a historical geographer and resident of Kamloops, I must quibble with some aspects of McGillivray’s description of the Southern Interior region, better known as the Thompson-Nicola. The Thompson River was not a “highway” for the fur trade – the “highway” was in fact the “overland trail,” an Indigenous route that fur traders used (and after 1821 was known as the HBC brigade trail), shown in Figure 5.3. The brigades were horse trains, not well-armed units as McGillivray suggests. The South Central Interior region was also the site of the earliest gold discoveries on the BC mainland, at Nicomen near Lytton and at Tranquille near Kamloops, which were in part responsible for the major rush in 1858. Cattle drives came through the region as early as 1859.

McGillivray states that the South Central Interior region “extends … to Revelstoke on the Columbia River,” but Revelstoke is shown in Figure 1.6 as in the Kootenay region. Indeed, a quick website search shows that Revelstoke is indeed in the Kootenays. The Kootenay region (which I think should be properly called Kootenays) is commonly subdivided into West and East.

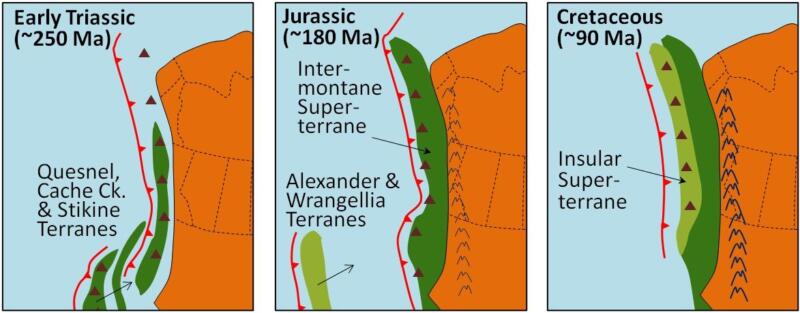

The figures in Part 1 of Geography of British Columbia are mostly the same as those in the second edition. While Figure 2.9 on terranes is corrected, Figure 3.10 on tsunamis is new, and the Richter Scale table has been dropped.

The second chapter on physical processes is also “boiler-plate” material, describing basic geology, plate tectonics, terranes, weathering and erosion, and climate. Chapter 3 on Geophysical Hazards includes an important section on wildfires, which are becoming more common and dangerous as a result of global warming. Table 3.1 on wildfires is updated to 2018. A map showing the epicentres of earthquakes in BC, pointing out the most vulnerable areas, would have been informative.

Following Part 1, McGillivray deviates from the thematic approach of his earlier editions to a chronological approach derived from historical geography, which works wells in describing the changing development of the province. The second part of the book, focussing on economic geography, shows how the exploitation of natural resources dominated the development of the province until the late twentieth century when service industries took hold, which have since spurred growth. In describing the geography in this era McGillivray takes on a decidedly political tone.

From Chapter Four onward, the text dwells on economic geography. Chapter Four concerns Resource Development and Management, with discussions of Staples Theory, Fordism, post-Fordism, and Globalization, but I feel that this chapter would work better in Part Two of the book, The Economic Geography of British Columbia. Chapter Five, Discovering Indigenous Lands and Shaping a Colonial Landscape, could have been switched to Part 1. Figure 5.1, showing the traditional territories of First Nations, has been brought up to date from previous editions but could have been enlarged to make it more readable. The boundary between the Ktunaxa and syilx/Okanagan is controversial, requiring an analysis of different sources.

Whereas the Third Edition followed a more thematic approach to topics of BC geography, Chapter 6 in the Fourth Edition covers the period after Confederation followed by a chronological approach in the following chapters: the early twentieth century, the postwar boom (Chapter 8), the late 20th century (after 1972) with a discussion of provincial politics and their impact on resource use, and the Twenty-First-Century Liberal Landscape (Chapter 10).

Inserted in Chapter 7 is a long but important discussion of race, concerning Chinese, Japanese, and South Asians, as well as First Nations. The map from the third edition showing Japanese internment camps during the Second World War, and locations of major Chinese communities, would have been appropriate in this new edition.

The whole chapter devoted to First Nations in the third edition has now been spread through the new edition in its chronological format. Treaty Eight, for example, is covered in the Post-Confederation Chapter 6. The maps of Nisga’a territory and Tsawwassen Treaty Lands in the third edition could have been used in the Late Twentieth Century (Chapter 9), but instead have been dropped.

Two maps I thought were of interest in the second edition, of instant towns and railway lines, have also been dropped from this edition. While these two topics are covered in the narrative, they require the reader to go searching elsewhere. Indeed, more maps as opposed to graphs and tables would have enlivened the latter part of the book.

Two other maps need revisions. Figure 3.5, showing the Lower Fraser Valley flooding in 1948, lacks detail — for example, part of Sumas Prairie was flooded despite diking on the east side. Dikes existing at the time could have been added to the map. As well, Nicomen Island is shown unscathed, yet it was completely flooded in 1948. A link could have been included here in the chapter references to the Lower Mainland Emergency Planning Floodplain Maps, Province of British Columbia. Much information and photos can be found about the 1948 flood.

Figure 5.2 delineating Alexander Mackenzie’s route to the Pacific in 1793 should show his voyage reaching farther south along the Fraser River. When he found that canyons and rapids would prevent his exploratory party from continuing by canoe, he backtracked and used the West Road River north of Quesnel to reach Bella Coola and the Pacific. As well, a typo — the misspelling of Finlay River, named after fur trader John Finlay — stands out.

As one would expect, Part 2 contains more changes to bring economic information up to 2020. The populations of the economic regions and regional districts (Table 9.3) could have been even more up to date, considering that employment by economic region (table 9.4) is current to the year 2000. I find it interesting to compare the vernacular regions shown in Figure 1.1 with the regional districts and economic regions. We still use vernacular regions in everyday parlance but economic regions are how the government plans and gathers data. Yet the average person has little conception, for example, of Strathcona or Mount Waddington regional districts.

The book’s 12-page conclusion is the opportunity for McGillivray to bring topics up to the present. As well, here he makes his main argument that British Columbia as a “commons” has squandered its natural resources. This may be true, but to say almost in the next breath that “resources are no longer the backbone of BC’s economy” ignores the fact that natural resources — forests and vegetation in general, wildlife, and water — have values vital to tourism, biodiversity, and sustainability. Indeed, the recognition of Indigenous title and rights is a foundation for the preservation of natural resources. While the traditional view of natural resources has changed, they remain, I would argue, the backbone of the new economy.

BC is no longer a resource-dependent economy but now an urban, service-based economy. However, although McGillivray calls “resource dependency” a myth, climate change is tied to carbon levels, which are tied to fossil fuels, which are intimately connected to the continued production of coal, oil, and gas. BC’s forests are an important sink for carbon. We should then look at resources in another way. First Nations are intimately connected to the land and so too the land’s resources. To suggest that dependency on resources is over may not be what First Nations would like to hear.

My main criticism of Geography of British Columbia is the gaps created by the omission, for example, of descriptions of biogeoclimatic zones and maps of mines, pipelines, and dams from the Third Edition. The Kitimat project of the 1950s lends itself to a classic case study of a company town based on natural resources, including waterpower and global trade in metals. I would have liked more case studies with accompanying maps on agriculture, tourism, and company towns. Some colour plates would have enhanced the book, such as that of vegetation patterns (Figure 2.19) and First Nations (Figure 5.1), but understandably production costs go up with colour. The book’s length, at 242 pages, is 40 pages less than the third edition, hence the reduction in figures and less emphasis on certain topics. However, interested students should be able to access earlier editions for topics that have been subtracted.

Still, the essential ingredients are all here, including a glossary of complex terms from each chapter that will be useful for students studying for exams, as well as references and a list of readings for each chapter, and an index. Despite the condensed format of this new edition, there is still no lack of detail in the text, which covers the main themes in a clear and concise manner. Geography of British Columbia remains an excellent overview of BC geography. Presumably it will continue to evolve over time and we can, I hope, expect a 5th edition in the fullness of time.

*

Ken Favrholdt is a freelance writer, historical geographer and museologist with a BA and MA (Geography, UBC), a teaching certificate (SFU), and many certificates as a museum curator. He spent ten years at the Kamloops Museum & Archives, five years at the Secwépemc Museum and Heritage Park, and four at the Osoyoos Museum. He has written extensively on local history in Kamloops This Week, the former Kamloops Daily News, the Claresholm Local Press (Alberta), and other community papers. Ken has also written book reviews for BC Studies and articles for BC History, Canadian Cowboy Country Magazine, Cartographica and Cartouche (for the Canadian Cartographic Association), and MUSE (magazine of the Canadian Museums Association). He taught geography courses at Thompson Rivers University and edited the Canadian Encyclopedia, geography textbooks, and co-edited a commemorative history (forthcoming) for the Town of Oliver and Osoyoos Indian Band. Ken is now working on books on the fur trade of Kamloops and the gold-rush journal of John Thomas Wilson Clapperton, a Nicola Valley pioneer and Caribooite. As an archivist and historical geographer he has undertaken research work for several Interior First Nations. He has visited and lived in all but one of McGillivray’s eight regions, the Kootenays. He now lives in Kamloops.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1305 McGillivray’s essential geography”