1284 A voice for the mute swan

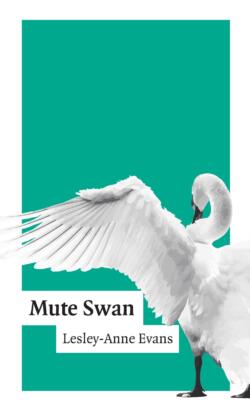

Mute Swan: Poems for Maria Queen of the World

by Lesley-Anne Evans

Toronto: The St. Thomas Poetry Series, 2021

$20.00 / 9781928095071

Reviewed by Cole Klassen

*

Mary and the swan: feminine symbols too often detached from reality

Mary and the swan: feminine symbols too often detached from reality

34 years ago, Lesley-Anne Evans was excommunicated from her fundamentalist evangelical church for being engaged to a Catholic. If this event had not happened, her first poetry collection, Mute Swan: Poems for Maria Queen of the World, might not have come to be. Rather than explicitly examining excommunication, Evans chronicles the long process of pain and growth following it, as well as the predicament of being a woman within an institution that preaches “blessed are the meek” while silencing those who step out of line.

The book begins with the line “1. There is no angel” (p. 11). It’s too easy to make the symbol of the angel perfect, as they are dreamed. Although there are frightening angels, like the eye-covered Ezekiel 10:12 angel, they live in our minds and drawings. Another white symbol of purity — not as divine as the angel, yet just as elegant — is the swan. And the swan is not imagined. If you get too close, they will snap at you, then they’ll take a poop. They have been known to break limbs with their strong wings when threatened. The simple distance between us and the middle of the pond has detached our understanding of the name swan from reality.

Mute Swan is split into five chapters: “Supposing,” “Furthermore,” “Likewise,” “Unless,” and “Unbeknownst.” This structure gives the cheeky air of a rhetorical argument — theses nailed to the door by a woman advocating for a less dogmatic and hateful version of Christianity.

The first chapter, “Supposing,” focuses on Evans’ early experiences with fundamentalism. Another word for “supposing” is “assuming,” and this chapter fittingly focuses on the time of life when our parents’ word is truth. In the breathtaking poem “Lament by the Faery Tree, With Angry Angels,” the speaker recalls life as a powerless child: “I bridge the Atlantic — /my identity is//what they tell me: Canadian,/Christian, fundamental,//apart” (p. 13), Evans writes. When people are given an identity they did not self-construct, they are separated from many real possibilities. The speaker begins by considering their lost Irish identity — the lost magic of faeries. The poem proceeds to mine the depths of fundamentalist identity-invasion; the speaker says “I carry the sins-of-the-people/in small packages; shame, guilt,//earrings I steal from Simpsons,/each time my mother asks//are you not cold with those/bare arms and legs?//Each time I bring//myself to orgasm” (p. 17). The biblical Mary that Mute Swan is dedicated to appears here for the first time: “Mary, an emptied container/packed away and opened at Christmas” (p. 14). In a church where the lives of women are brutally policed via shame, Mary is an empty signifier — a name and symbol that peddles hollow reverence of women and the marginalized.

Each chapter in Mute Swan begins with a “Testimony” of numbered paragraphs that demonstrate the chapter’s mood and rhetorical direction, and the second chapter begins with “Testimony Two: After Fireside a Bunch of Us Hang Out.” Evans writes: “9. OK, so if we have free will, but/God knows what we are going/to do before we do it, how is/that our choice?//10. I’m getting a purity ring for my/birthday” (p. 30). This poem is self-aware of the corniness of Christian teen drama, yet it does not lose track of the underlying darkness and control thanks to gut-punch lines like the mention of the purity ring: the ultimate agency-destroying artefact.

In the third chapter, “Likewise,” the speaker expands the discussion into new realms of silence. For instance, the silence of conservative Christians when it comes to protecting marginalized people: “What if loving our neighbour/is the commandment//we will not speak?” (p. 55). “Likewise” is a way of saying “me too,” and this chapter highlights those who have faced oppression even harsher than the silence forced upon Evans by her fundamentalist church. The sobering poem “What you Carry,” which received first place in the 2019 Federation of British Columbia Writers Literary Writes Contest, focuses on the cruel internment of Japanese Canadian people in BC from 1942 to 1948. The poem frequently repeats a phrase said by a cop: “You can take what you can/ carry on your back” (p. 53). The mantra-like presentation of this phrase highlights not only the almost ascetic snail-shell-like burden faced by those without home, but also the continued existence of this problem; the VPD and the RCMP frequently tear down tent cities.

The poem “On the Eighth Day We Name All Things Troubled and Beautiful” delves into the plights of Indigenous peoples. For the most part, this is handled sensitively. However, small moments seem not-so-sensitive: “everywhere I hear/their stories. How her father//raped her, how he endured//residential school, how/they keep each other warm//in ‘Tent City’ minus ten nights — /while I decide, beloved,//…you are” (p. 60). Many people mentioned in Mute Swan are noted in the acknowledgements, but this anonymous, homeless First Nations family is not. Did they want their story shared? Regardless of the answer, should their traumatic story be a component of Evans’ reflection on her God? Especially considering Christianity’s history of Indigenous genocide, this is perhaps problematic. I won’t scrutinize this any deeper because, although I feel obligated to point it out, it is not my place as a white person to decide if this is acceptable. Any reader will sense that Evans has good intentions. Good intentions do not justify insensitivity, but remind us this is a huge step forward compared to most Christian writing, which rarely acknowledges the incredible suffering beyond the high walls of white privilege.

In the final two chapters, “Unless” and “Unbeknownst,” the swan enters the forefront. The poem “Triumphant Arrival of the Mute Swan” ends with these lines:

In all, Mute Swan, you have a voice —

one has to wonder at

the mis-naming.

Each time your song roars forth

a curse ruptures.

You are mystery. You are us —

audacious in loving the holy present,

in finding ways to speak of it.

How blatant you appear to us now that we are you.

How raucous to proclaim our theories

to the wide sky —

the sound of our wings

heard a mile away (p. 75).

Before reading this book, I did not know that the species of Swan we imagine when we hear the word — pure white, S-curve neck, black-tipped orange beak — is the mute swan. Evans cleverly uses the inaccuracy of this name as a metaphor for the oppressive power of misnaming, the oppressive power of discounting voices through symbol and tradition.

The powerful unmuting which takes place in these final chapters is a kind of birth. Evans uses this context to bring the focus back to Mary. In the visceral poem “Blessing for Midwives and Birthing Rooms,” Evans highlights the too-often-silenced grit of women:

I rise

— hands bloody with Ulster —

woe to those

who say otherwise.

Are you

speechless? My skin

is a highway. Unfurl the banner

of my hair and I will dance

on this sacred earth,

my palms

to the stars —

spilled saucers of milk (p. 90).

Birth — where we are all created — is the ultimate moment of feminine strength counter to the symbol of the delicate, quiet, and powerless woman. “Spilled saucers of milk” is a metaphor that beautifully conveys simultaneously nurturing and wild femininity. Men will never know the level of pain and chaos involved in birth, yet they lead churches that do not allow female elders, rendering Mary nothing but a vessel.

Everyone has been silenced at some point, so I believe Mute Swan will provide a moving read to many poetry enthusiasts. I thoroughly enjoyed experiencing Evans’ poetics, yet I think my existential and not-so-optimistic perspective prevented me from appreciating it as much as some would. Like anyone, I am not apolitical; as a queer person who was taken to a conservative church in my youth, I am, unsurprisingly, averse to Christianity. However, I am so glad to see a Christian, British Columbian poet challenging mainstream evangelicalism. Sexism within conservative Christianity is a problem Evans has faced in a terribly real way, and as a result the book’s feminist moments are incredibly poignant.

The birth of a new ideology from an old ideology, like swans, involves both beauty and grit. In the final moment of Mute Swan, the focus shifts to beauty — the possibility of a world where your true self is not muted by those surrounding you. Evans cunningly illuminates a common ground between Swans and Christians: water. A utopic baptismal moment occurs and it is deceptively simple: “I step wet/from the bath//into your waiting eyes.” Here, Evans does not imagine a new baptism, but a new God: a God that does not use shame as a power tool. Perhaps what renders conservative branches of Christianity so oppressive is less how they see God and more how they decide God sees them. God is the watcher, the other; when you exist in a church, what God dislikes is what the community surrounding you will dislike. The gaze of others is a means of control fearfully familiar to women, so this utopian gaze — where all is accepted — is a fitting end to this striking feminist book.

*

Cole Klassen is a genderfluid musician, poet, and teacher living on the stolen traditional, ancestral, and unceded land of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations — otherwise known as East Vancouver. They are currently pursuing an MFA at The UBC School of Creative Writing, where they study poetry, songwriting, and pedagogy, and also work as TA Coordinator. Cole has been a writing and music educator since 2013. They have volunteered as a first reader at UBC’s PRISM International, and served as a 2021 New Shoots Mentor educating high school students in creative writing. They performed at the 2020 Vancouver Writers’ Fest. Their work can be found in Discorder Magazine, Douglas College’s PEARLS anthology, UBC Life Blog, and UBC’s NineteenQuestions blog. They are a recipient of Douglas College’s Maurice Hodgson Creative Writing Award of Distinction. Cole plays bass in the punk band Swather, which can be found on Spotify. The band they lead, TALL MARY, released a single in 2020 on Bandcamp, and a full album is forthcoming February 2022.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster