1273 Ancient craft, long history

Mining Country: A History of Canada’s Mines and Miners

by John Sandlos and Arn Keeling

Toronto: James Lorimer and Company, 2021

$29.95 / 9781459413535

Reviewed by Robert G. McCandless

*

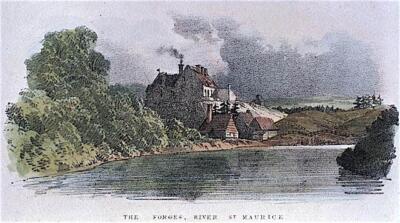

The introduction to this attractive book says Canada’s mining history is “curiously neglected,” then steps into that gap to present two hundred years of history. Starting from eighteenth century iron production in Quebec and through to mining in the current decade, it describes famous mines like Sudbury (ON), Asbestos (QC) and Sullivan (BC), and dozens of others, from coast to coast and from the high Arctic south to the Great Lakes. The authors describe five facets of their big subject; Indigenous people; mine workers; mining communities; pollution from mining; and the place of mining in Canadian history. It presents histories of selected mines in a fluent and engaging way within their regional history and geography.

The introduction to this attractive book says Canada’s mining history is “curiously neglected,” then steps into that gap to present two hundred years of history. Starting from eighteenth century iron production in Quebec and through to mining in the current decade, it describes famous mines like Sudbury (ON), Asbestos (QC) and Sullivan (BC), and dozens of others, from coast to coast and from the high Arctic south to the Great Lakes. The authors describe five facets of their big subject; Indigenous people; mine workers; mining communities; pollution from mining; and the place of mining in Canadian history. It presents histories of selected mines in a fluent and engaging way within their regional history and geography.

The authors teach at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador. John Sandlos a historian, and Arn Keeling a geographer, have studied environmental degradation and contamination at abandoned mines in northern Canada. Their knowledge of those sites gives real strength to the book, but this does not offset a glaring weakness — it has no maps! The reader must use other sources to find, for example, Canada’s diamond or uranium mines. Its otherwise commendable view of mining’s history has a second weakness: a consistently accusative, even tendentious tone. Beyond these faults, Mining Country will appeal to anyone who worked in mining or lived in mining communities, and will inform those interested in learning about the place of mining in Canada’s history.

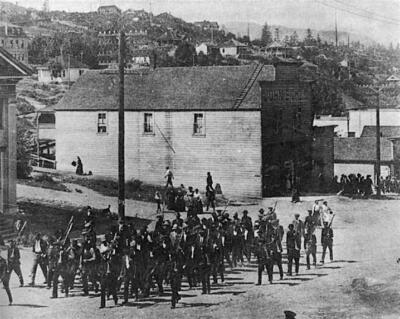

Chapters One and Two present an engaging summary of Canadian mining history from the 1700s to the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896-98, including roles taken by Indigenous people, mining labour and the first unions, and the evolution of improved mine safety. The histories of some very old mining locations are brought to the present in an adroit way that stresses their formative role in regional history. This part lacks even a brief explanation of how evolving technology made mining much more profitable: railway and telegraph networks, more efficient steam power and compressed air tools, better steels, safer explosives, and enthusiastic American and British investment capital.

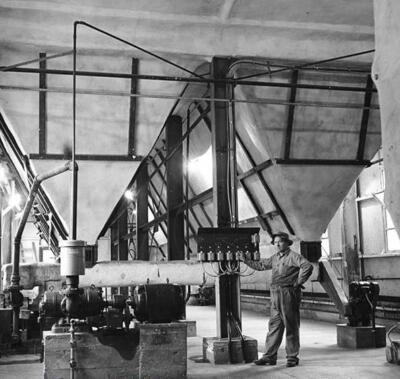

Chapter 3 describes the rapid growth of Canada’s metal mining industry with examples of large mines like Sudbury and Noranda in central Canada, and Sullivan and Britannia in the west. The authors state their intent to show “that the expansion of mining activities during the boom years often carried dire social and environmental consequences, the brunt of which was sometimes borne by First Nations communities in remote areas newly opened to development … mine managers constantly sought to wring more concessions and efficiencies from workers to satisfy the push for profitability among owners and/or shareholders” (p. 84).

These perspectives guide the authors as they shuttle site-specific details — arsenic near Yellowknife, radioactivity near Elliot Lake, acid rain near Sudbury and Trail — between descriptions of mine workers and their health; mine safety standards; the opening of new transportation routes and the brief lives of company towns; the evolution of mine permitting and safety; and more recently, impact and benefits agreements between mines and adjacent Indigenous people. These give the book a consistent narrative fabric but it’s too thin to clothe this ancient craft and its modern form in ways that explain, if not celebrate its great transformative power; nor will it inform and guide development of better mining policies.

Current historiography demands expressions of guilt and remorse over themes like displacing or ignoring Indigenous peoples, or creating abandoned, chronically-polluting mines. The authors do this to a fault: the repetitions will date the book, and cause some readers to put it down and turn away. That would be a pity. The facts they present can’t be found anywhere else between two covers, and those facts need to be known to help the sector evolve and move us ahead.

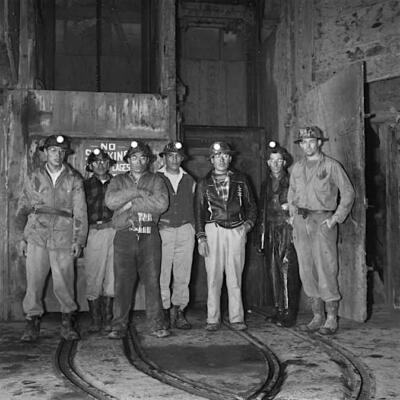

Chapter Four describes the expansion of mining from the Second World War until the 1970s. Its good overview of Canada’s little-known but crucial role in supplying strategic metals for the Allied war effort does not mention the federal-provincial cooperation that made this possible. The chapter has well-written histories of a dozen famous but now-forgotten postwar mines including; the 1958 Springhill Nova Scotia coal mine disaster; workers’ struggles in 1949 at Quebec’s asbestos mines; development of new gold mines in Yellowknife and consequent arsenic pollution; and the boom-bust-boom of uranium mining. These examples show both the benefits, and the human and external costs that attended mining’s rise to economic prominence.

Chapter Five presents examples of new mines and their effects from the 1970s to 2016. This period continues today with the industry adapting to a complex approval process that includes comprehensive environmental assessments, and bilateral agreements between mines and adjacent First Nations, especially in the northern territories. The chapter presents very well continuing efforts to assess and remediate chronic pollution from abandoned mines. Cleanup costs could be reckoned in the hundreds of millions and climbing, which the authors seem to imply Ottawa will pay for: what happened to polluter pays?

The polluters, the former mine owners, could be compelled to pay something, but it’s complicated. Canadian provinces emulated American “Superfund” laws when they legislated power to assign “absolute, retroactive and joint and several liability” to a contaminated site’s owners. Could this tool be used to fund cleanup of abandoned mine sites? In the provinces, maybe; but not (yet?) in the North. In 1997, British Columbia first applied this tool to compel cleanup of contaminated industrial land, and in 2003, kept it at hand when it persuaded former owners of the Britannia Mine to pay $30 million towards the much larger cleanup cost now borne by BC taxpayers.

Using retrospective legislation to assign liability for contamination sounds unfair, but in 2003, the Supreme Court of Canada gave it a ringing endorsement.[1] When corporations merge, liability for environmental contamination gets passed along just like real property, and it is difficult to evade. A province can round up “potentially responsible persons” (PRPs), like present and former site owners, and negotiate who does what, and who pays. Doing this for the arsenic contamination at Yellowknife might be an interesting case, if and when federal and Northwest Territorial laws allow it, to track ownership through owners like Falconbridge to its huge successor, Glencore PLC of Switzerland and the United Kingdom. But our political will to wield retrospective liability seems lacking. Maybe Canadians have a curious modesty that makes us reluctant to follow the money. The path of liability might lead to (God forbid) dividend-paying companies owned by pension funds.

The book presents a close and sympathetic view of a second big topic, industry’s acceptance of the transformation of the permitting process for new mines, through environmental assessments and impact and benefits agreements with adjacent First Nations. The authors are right to point to the 1974 Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry as setting the standard. Since then, permitting has used negotiations to balance between competing requirements between a company’s need for access to minerals against assignment of economic benefits — cash payments, training, jobs and contracts — and joint auditing of environmental protection requirements and compliance. Such negotiations may fail, and what was seen to be ore, reverts to being mineralized rock. Working within these agreements has now become part of good professional engineering and geoscience practice.

The development of the Voisey’s Bay nickel mine in the 1990s in Newfoundland and Labrador is described very well. Among other terms, its permits reduced the mine’s ore production rate to prolong the mine’s life and its flow of local economic benefits. Some of the earliest impact and benefits agreements between mines and First Nations were confidential, and problems can arise from this. Public companies are required to publish management discussion and analysis (MDA) reports which must state its obligations, but a First Nation can set its own terms. The benefits brought by new mines can dislocate local economies and risk causing income disparities that a First Nations may have to struggle to solve.

Mining Country is an ambitious and successful book that needed to be written, but flawed by its lack of maps. Its bibliography is excellent but its index seems much too sparse. It should use metric units throughout. It lacks even general remarks about Canada’s geology, especially the Canadian Shield and its mineral bounty; the history of raising development capital and the loss of the sector’s reputation in the Bre-X scandal; and something should be said about provincial mineral tenures and the centuries old “free entry” system now being challenged by First Nations.

Mining is not seen in a good light these days, and its further decline seems inevitable. Proven and undiscovered ore can wait for better days, but not Canada’s pool of talent for finding mines and bringing them into production. More of these men and women will learn Spanish and move south and their loss will leave us poorer.

*

Robert G. McCandless practiced as a professional geoscientist until retirement in 2009, after 28 years with Environment Canada in Whitehorse, Ottawa, and Vancouver. Previously he worked in oil and gas exploration and mining. While living in the Yukon, he wrote Yukon Wildlife: A Social History (University of Alberta Press, 1985). With government he worked on pollution prevention in the mining sector, and also advised on Aboriginal affairs including treaty negotiations. After retirement he has published three articles on natural resource and history topics for the journal BC Studies: on BC offshore petroleum exploration (BC Studies No. 178, Summer 2013), Britannia Mine pollution (BC Studies No. 188, Winter 2015/16), and BC Mining in World War Two (BC Studies No. 211, Autumn 2021). He lives in Delta, BC. Editor’s note: Robert McCandless has also reviewed a book by Catherine Spude for The Ormsby Review

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Supreme Court of Canada, 2 SCR 624, Imperial Oil Ltd vs Qubeec.