1186 Excuses: a preemptive review

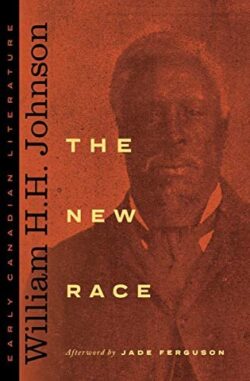

The New Race: Selected Writings, 1901-1904

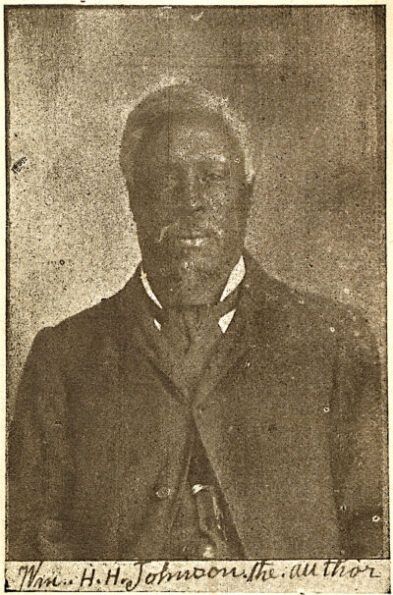

by William H.H. Johnson, afterword by Jade Ferguson

Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, forthcoming 2022

$19.99 / 9781771124140

Reviewed by Frank Mackey

*

My only excuse for writing this account of a book yet unpublished is that I grew tired of waiting for it. The request had come in 2019 to review the book, a re-edition of a 1904 work, scheduled for publication that May. Repeatedly delayed, it is now due out in November 2022. “It’s now or never mind,” I thought, found an online version of the original[1] and went to work.

My only excuse for writing this account of a book yet unpublished is that I grew tired of waiting for it. The request had come in 2019 to review the book, a re-edition of a 1904 work, scheduled for publication that May. Repeatedly delayed, it is now due out in November 2022. “It’s now or never mind,” I thought, found an online version of the original[1] and went to work.

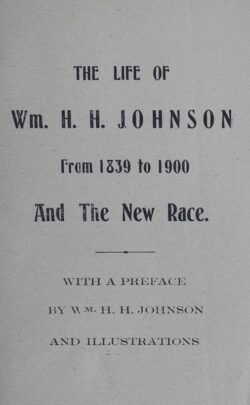

The Life of Wm. H.H. Johnson, From 1839 to 1900, and The New Race[2] was published in Vancouver by Bolam & Hornett of 308 Water Streer (sic). That seemingly insignificant typo at the front of the book is a tick-sized hint of the many bugs inside. This gangling sentence in the dedication doesn’t bode well, either:

Mr. Wm. Shackelford was one of the main leaders of the New Race, and after remaining in slavery for a number of years, and after purchasing his wife and himself, and paying nearly two thousand dollars for their freedom, he located near Windsor, Ontario, A.D., eighteen hundred and fifty-three, and bought and cultivated a highly improved farm, and became very wealthy, and at his lamented death, which took place A.D. eighteen hundred and ninety seven, he left all of his children and grand children in very good circumstances.

Shackleford died in 1896 (13 April), not 1897, as Johnson, a resident of Windsor, Ont., for 34 years (1856-1890), should have known. And “and” appears 11 times in that one sentence! As biography, history, CanLit, etc., this Life gets off on the wrong foot.

Shackleford died in 1896 (13 April), not 1897, as Johnson, a resident of Windsor, Ont., for 34 years (1856-1890), should have known. And “and” appears 11 times in that one sentence! As biography, history, CanLit, etc., this Life gets off on the wrong foot.

What was Johnson’s excuse for writing it in the first place? “Several philanthropic gentlemen in this city have asked me to write a history of real incidents which I have experienced during my life and as I have been afflicted for over a year with and from the effects of la grippe, I thought I would make an effort to the best of my ability,” he tells us. Born a black Hoosier, he had worked as a store clerk in Ontario, a sailor on the Great Lakes, a varnish-maker in Ontario, then in Vancouver, and ultimately, a barber on Abbott St. Untrained as a writer, idled by illness but egged on by friends, he determined to write his story, he claims. Yet we know he had begun work on his Life before this: Its last four chapters had been published in 1901 as The Horrors of Slavery.[3]

Not every printed work deserves a second chance. Does this one? It is not particularly gripping, sheds no new light on slavery, and is no guide to black B.C. The work to be published by Wilfrid Laurier University Press, under the title The New Race: Selected Writings 1901-1904, will no doubt attempt to answer the question. Will the new edition constitute a radical reworking of the original? The new title suggests that it will shift the focus from Johnson to the “New Race,” about which he had little to say. Let’s hope the excuse goes beyond plugs for “the only classical slave narrative in the black North American tradition published by a British Columbian.”[4] Slave narratives were essentially weapons in the war against slavery. By 1904, that war was done and the New Race was getting on. And Johnson’s late account was no more part of “the black North American tradition” – if by that is meant a Canadian-American tradition – than the life stories of U.S. slaves in Britain were part of “the black British-American tradition” or “the black Atlantic tradition.” It was part of an American tradition.

To rewrite is human

The new version definitely needs an edit to deal with “beastile” passages such as these:

At the battle of New Orleans and other battles, nearly all of my people took part in the war of 1812, because the forty five black people that were brought from Africa to Virginia in the year 1620 had increased to many thousands.

My father thought he would move from interior of the state, which he did, taking his wife Vernon farthr into the interior of the state, which he did, taking his wife and family to Greensburg, in the same state, where he occupied the same honorable position as station master on the “underground railroad” …

I have myself been an eye witness of the what I have seen there is proof enough to show that man’s nature, unchecked, would be beastile.

Will it be “General Wallace” or Cornwallis who surrenders to George Washington at “York Town”? Will Haitian emperor Jean-Jacques Dessalines banish “Pirie Jacques Desolines” forever? Will U.S. slavery end in 1863 or 1865? We must wait till 2022 to find out. Some cleanup, fact-checking and spell-checking is in order, and a timeline would be helpful, but a radical editorial scrubbing, as desirable as it might be, would destroy the original’s rough authenticity.

There are, to be fair, some bright flashes between the errors. Take the opening sentence of Chapter 7: “But it is a long dream that lasts till morning; and so my childhood happiness had to come to an end sooner or later.” Did Johnson write that? It fairly sings. And here is a League of Nations premonition: “It appears that all or the most of history, is war history, as much as anything else. I was in great hopes that all nations would form a tribunal to settle all national disputes by arbitration, but it appears not … ” Dovish Johnson betrays a hawkish heart, however, when he suggests he and most Blacks would fight on Britain’s side in a war because … Britain is Great.

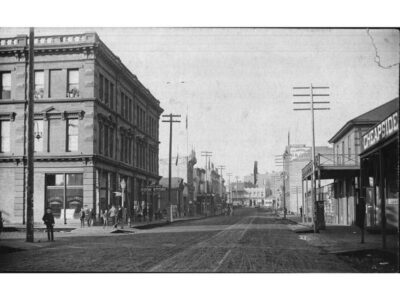

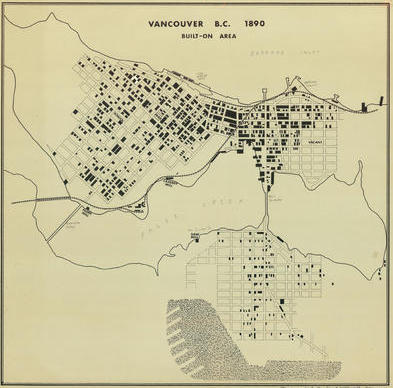

In 1890, after 35-odd years in Ontario, he lands in Vancouver. “Vancouver has a great cmfwy shrdlu shrdlu shrdlu hr couver is a beautiful city with a grand location.” Curse the typesetter! But shouldn’t Johnson have pulled this passage – and another like it – before his book went to press? Fortunately, he had more to say about Vancouver:

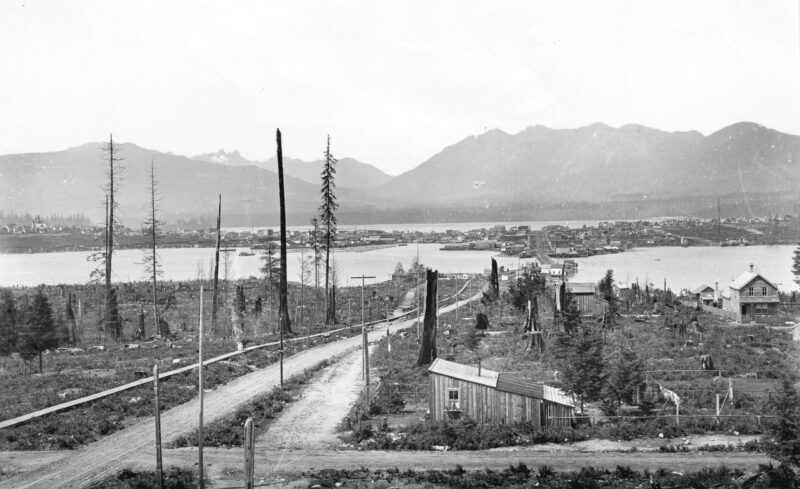

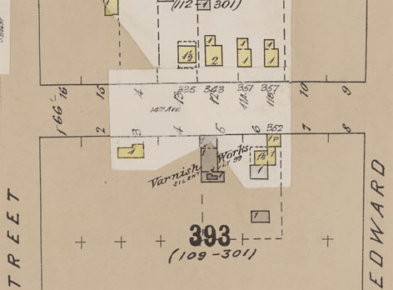

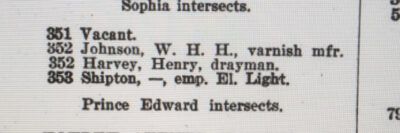

Shortly after my arrival in this city I secured a location on which to build a house, on Fourteenth avenue, Mount Pleasant, which was then comparatively a wilderness, though in every other way a charming location. My wife was well pleased with the change, especially as regards the climate, the winters here being much milder than in Ontario. We found the people in Vancouver very friendly, and in fact I cannot say that I have ever lived among a more sociable set than in this city. In a general way I have got along very well since coming to Vancouver. After clearing a couple of lots I erected a shop and started the manufacture of varnish, but not having sufficient capital to compete, I was forced to give it up.

He was a varnish-maker almost to the end, latterly as an employee rather than as his own boss. And the end came when? Everyone’s best guess is sometime in 1905.

‘Smart as any man I ever met’

To an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) missionary in 1893, he was exceptional:

There are 165 colored persons in Vancouver, counting young and old … and their occupation is as follows: 19 barber shops in which are from two to six chairs, 8 janitors, 1 elevator runner, Mr. F.R. Graham, of Lawrence, Kas., 1 restaurant, Mrs. H.M. Walker and husband of St. Louis, Mo., 1 varnish manufactory, which is owned and controlled by Mr. W.H.H. Johnson, of Windsor, Canada, black as jet, but as smart as any man I have ever met, white or black. The balance of our people do nothing but loaf about and gamble.[5]

Rated one of the “very wealthy men of color in British Columbia,” living in a six-room house in Mount Pleasant,[6] Johnson had certainly come up in the world. He was born in Madison, Ind., on 23 November 1839, to John L. Johnson, a free black son of Indiana, and Mary Ann, a fugitive slave from Milton, Ky., across the Ohio River. She, like other Milton-area slaves, often crossed to Madison to see friends. One day she crossed and stayed. Her owner did not sic the hounds on her.

She named her son after Gen. William Henry Harrison, the resolutely pro-slavery governor of the Indiana Territory 1801-1812 (statehood came in 1816), military hero, and U.S. president-for-a-month (4 March to April 1841). Johnson’s mother told him “there was a gentleman that lived in Madison at that time who told her if she name [sic] me after General Harrison, that he would give me a suit of clothes, which I would have gotten had we remained in Madison, but we left after the great mob.”

Rampaging white mobs were one factor that led the family to move north to Vernon, where they farmed; then to Greensburg, where his father opened a restaurant and barber shop; and, in 1848, to Indianapolis, where his father apparently studied medicine while working as a barber. Here Johnson, denied access to white schools, first learned from a black teacher how to read and cipher. The Johnsons dreamed of moving to Liberia, but when the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made life unbearable, “No place short of Canada held any hope for us.” They resolved to join kith and kin in Amherstburg, Ont.

slave in theory

“Here for the first time in our lives mother and we children sat [sic] foot upon the soil of a country in which we were really free,” Johnson wrote. “What this means can be known only to those who have experienced slavery.” Had he experienced slavery? Of Amherstburg he says, “It was there that I first learned I had been born a slave, in a free state.” His mother having been a slave, her children unknowingly inherited that status. Before the Fugitive Slave Act, slave hunters had often harried the Johnsons, suspecting them of harbouring fugitives, but they had never fastened on Mary Ann as a fugitive, or on her “slave” children. “Although born a slave in a Free State I was never a slave in practice,” he says. Slave in theory then. In that case, to treat his tale as a classical slave narrative would be to devalue the experience and narratives of “slaves in practice.”

Besides, his view of slavery in practice was offensive:

… [T]hese people at least became civilized and learned Christianity. I have noticed in many ways that good will often come of evil; for instance, when the sons of Jacob sold their brother Joseph into bondage in Egypt he afterwards was the means of saving his people from starvation.

I have thought sometimes that it was a great blessing that our people had this opportunity to learn civilization and Christianity that they might eventually return to their own country and impart the knowledge to their own people.

But if we had remained in Africa me [sic] would not have had the opportunity to receive the light that we now have, unless through some other channels and we would all have been as blind as the rest.

Since the United States colored people went to Liberia, many thousands of my race have been brought into the light and worship the true God, and many of the natives have been well instructed, and are now preaching the Gospel to the heathen in other parts of the country. So God in his superior widsom introduced His Gospel throughout the world among all nations, and slavery of my race – as I see it – was one of God’s mysterious ways of spreading his glorious Gospel.

Here God in his superior wisdom took a bow and, for an encore, ordered his followers to establish Indian Residential Schools.

In an 1893 letter to a U.S. paper condemning a Texas lynching, Johnson touted Canada as a haven for Blacks. Leave the South, he urged, “in this country there is a home and happiness for every honest man who seeks it.”[7] This kind of Canuck boosterism, present throughout his book, along with like views expressed by other Blacks, suggests that the representation of Canada as a land of refuge is no modern white delusion, as it is often portrayed, but a real, rare, black relic of slave days. Whites cling to it, Blacks don’t.

The big flaw

The sorriest feature of his Life is his suppression of names. He never identified his parents, grandparents, spouses, even his daughter, by name. (I inserted his parents’ names above.) Of his seven sisters, he only once named one, Amanda. It’s as if he had buried his nearest and dearest in unmarked graves.

He married three times. “In the fall of the year 1860 I got married and my wife caught the small pox, which was raging in Windsor at that time, and she died the very next week after we were married; that was my first real experience of heart felt trouble.” The Archives of Ontario correct him – his wedding took place on 26 November 1861, not in the fall of 1860 – and name his wife: Nancy Elliott, 26, daughter of Alfred and Mariah Jones of Virginia. The first we hear of wife No. 2 is when we bump into her at Cleveland on the steamer City of Toledo, on which he worked. “Among those who were on the deck was my wife and only child.” This wife, the Archives say, was Elizabeth Longotten of North Carolina, parents unknown, married on 15 August 1864 at age 20.

The 1871 census made him a married Windsorite of “African” origin, 36, a sailor. The 1881 census recorded him as a Windsor varnish-maker and a widower. He married his third anonymous wife, the U.S.-born widow Fanny Carter, née Brown, at Brantford, Ont., on 25 September 1883. She was supposedly 60 when she died at Vancouver in 1897, on 2 or 5 December, depending on whether you visit Mountain View Cemetery or the BC Archives. Her death record did not name her husband.

Why this hide-a-name game? You really have to wonder. Read The New Race when it appears and hope for answers.

*

Frank Mackey is a retired journalist for whom history is not a discipline but a tipsy pleasure, which sees him approaching the present by the 19th-century lane behind, looking over the messy yard, the ghost of a garden, the grass uncut for ages, and wondering if this is home. Author of Steamboat Connections: Montreal to Upper Canada 1816-1843 (2000); Black Then: Black Montrealers, 1780s-1880s (2004); and Done with Slavery: The Black Fact in Montreal, 1760-1840 (2010), published in French as L’esclavage et les Noirs à Montréal, 1760-1840 (2013). In the works, The Absquatulator, to be published next year by Baraka Books, barring pandemics. It’s a long story.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.78490/1?r=0&s=1

[2] “The name of ‘New Race’ was given to my people in San Domingo [Haiti] when they gained their independence in the year 1803, and strange to say, the same name was also given to us, after emancipation in the United States, sixty years later.” (p. 36)

[3] Of The Horrors of Slavery, Robin Winks wrote in The Blacks in Canada (1971): “In 1901, when a black sensationalist, William H.H. Johnson, published in Vancouver an essay filled with bloodhounds, mutilations, attempted rape, incest, floggings, and sudden discoveries of lost sons – the whole a potpourri of the fieriest of abolitionist tracts – Canadians reminded themselves, quite properly, of the irrelevance of this tale to their experience.”

[4] Wilfrid Laurier University Press catalogue, spring/summer 2019.

[5] Christian Recorder, Philadelphia, PA, 18 May 1893, letter to the editor from Dr. E.E. Makiell.

[6] Idem. Vancouver Daily Province, 29 May 1905, “For Sale” real estate advertisement, p. 9.

[7] Plaindealer, Detroit, MI, 17 March 1893, letter from W.H.H. Johnson, p. 4.