1178 The intelligence of deer trails

Waymaking by Moonlight: New and Selected Poems

by Bill Yake

Anacortes, WA: Empty Bowl Press, 2020

$20.00 (U.S.) / 9781734187342

Reviewed by Ron Smith

*

I’ve just finished reading Bill Yake’s Waymaking by Moonlight: New and Selected Poems. As I reflect on the complexity and insight of his vision, I’m left wondering why I’ve never heard of this wonderful poet before now. Put simply, his work is stunning.

I’ve just finished reading Bill Yake’s Waymaking by Moonlight: New and Selected Poems. As I reflect on the complexity and insight of his vision, I’m left wondering why I’ve never heard of this wonderful poet before now. Put simply, his work is stunning.

For one thing he’s remarkably inventive with language, with form, constantly adapting the shape of his work to serve his purposes, from long free verse poems to minimalist creations that could be characterized as haiku or ideograms; from rant, as in his distressing plea to America “Letter to America – A Version in Which a Mirror Shatters” to epigrams; from eulogy to meditation; from lists, as in “Found at a Homeless Camp,” to discovery to celebration. He does not use the language to record what he has seen but rather he sees through the language. The essence of what he perceives reveals itself on the page as if by magic; it is not mere response and description. Such composition is risky because it tests the unknown. It’s at the heart of inspiration.

I believe poetry has its origins in prayer and song, two ritual responses to what we are feeling, thinking, acting out, or doing. Eventually poetry emerges as the keenest and most enduring language form to embody our dreams, conquests, regrets, and hopes.

Language, first and foremost, is about our mutual understandings; it is predicated on what we share as human beings and as sentient creatures occupying a common habitat. All things, as far as Yake is concerned, and I concur, are entwined, are dependent on others; on all others. Flora, fauna. Mineral, water, fire and air.

Yake describes the writing process differently in the Preface to Waymaking by Moonlight: “A book is a trail the mind walks. A trail is a tale, a sequence the eye can read.” He continues elsewhere:

This was the collection — a trail. An indirect trail, a reticulated trail, maybe even a maze — but a trail none-the-less. Fifty years of chance and intention, inherited maps and apt suggestions. Random attention paid to visions half-seen out of the corner of one eye or the other. Temptations — forks in the trail — rejected or accepted.

In some places the trail was well-worn, in others a faint game trace, and some portions of the trail were marked with cairns or blazes. [You may have heard of chumstick? Chumstick Canyon, Creek and Mountain just outside of Leavenworth? Referring to a Chinook jargon dictionary, it says this: “painted/marked wood/tree.” A blazed-or-marked-tree. Signs marking the route, the true trail. This seems the likely reason the lean and hardy salmon, those whose males have red blazes marked on their flanks and who spawn near the mouths of west-side streams, are called chum.]

Blazes marked Howard McCord’s classes at WSU in the late 60s and his kind of poetry snared me. Words that resonated with something between my vision-dream-and-analytical attention, between forest openings and philosophical musings.

Howard quoted Ludwig Wittgenstein, “Is the fact that someone genuinely thinks he means something a guarantee that there is something that he means?”

To which he (Howard) had responded, “…the intelligence of deer trails is greater than that of the speech of man.”

The intelligence of deer trails. Perfect. That had been the inspiration and epigraph for a poem called Tending Trails that was in an invocation at the beginning of the collection.

Tending Trail

“…the intelligence of deer trails is greater than that

of the speech of man.” —Howard McCord

Through ravine and forest

we’re led by the mutual

intentions of foxes, racoons,

deer, and the predatory cats—

along the game-trails,

traces, and foot-paths

that track the phrenology

of the land: its stony skull and frame

and the direct, then winding, way

its creatures find from stream

to browse, from cover to clearing,

from safety to necessity.

We have joined that trek

—being curious and wanderers—

and scramble through the maze

at first, then place a stone

for a step where the way is steep

and set cedar rounds down

in swales where swamp lanterns

thrive, in the bottom-lands where

paw prints speak precisely of intent.

Later, we’ll return to brush out

sword ferns and the low cedar

fronds that crowd our tentative

human prowling; bring a mattock

to widen side-hill runs—to cut back

soil on the uphill slope, the sloughing

duff with its curled millipedes tucked

inside—the yellow-spotted, almond-

scented, cyanide-laced kind.

New fiddleheads and rich decay

will tumble from above. Then we

heap and smooth, widen and level,

rake and tamp the moist ground

down—retaining each substantial

root as foothold or intricate

step; leaving branch handles

intact to grasp—so when we come

this way, again, it will be only

a little less lightly

than the beasts.

Yake is comfortable with his perceptions and imagination no matter which trails he wanders, be they along the northwest coast of North America or more recently, taking exploratory trips to Papua New Guinea, Mongolia, Sicily or the illustrated caves of France. He observes and he listens. His poetry’s kin include Whitman, Gary Snyder, and Robert Bringhurst whose name Yake invokes in epigraphs to a couple of poems that register his passion and concern for the environment, and the peoples and cultures who understood their inseparable dependence on and connection to it.

One of my favourite poems is “The Hidden,” perhaps a song for SGang Gwaay, a UNESCO World Heritage Site on Haida Gwaii.

The Hidden

for the now-abandoned villages of Haida Gwaii

Begin with our present, tenuous foothold

by the sea. Walk inland and the green moss of forest

will swallow and hide you. Paddle seaward and the sky will swallow

you in cloud and the village in alder smoke. The sea drags

our long lines down. Our halibut hooks. We have seen

the Strait swallow whales whole. Walk backwards,

this time time will swallow you whole, tuck you

out of sight behind the house-skin, beneath

the earth-skin, turn you blue beneath the tricks played

by light on water, by water doing its dance of waves crossing

waves, by the flickering of candle fish. Nearby,

you hear a heart you cannot see;

six kin-Ravens gossip over food behind

a damp sheet of mist; their voices like trip-hammers

striking at small, wooden boxes. Specific pollens are falling

on water, years hence they’ll be keyed from layered sea muck

and bog varves: Cloud Berry and Calder’s Lovage.

Stories await decoding. All these slights

of hand, smearing winter tallow

and the char of shelf fungus

on our faces to face

the sea with all its death,

all death’s riffs and rifts, Survive this

and by the next turning you’ll hale midsummer’s

Fair-Weather-Woman with sweet-meats of blue mussel

when they catch, as they must, the scent

of this rich and wistful world.

The particulars of a place are important in Bill Yake’s work, which perhaps explains the power and musical richness of his poems. They are his response to the ecology, its diversity, and our place in it. His poems are a sharing of the essences of rivers, mountains, fungi, ancient forests, prairie, desert and birds in the hope that they will be heard and judged worthy of our solicitude and humility. They are a singing out in honour of nature’s bounty, birth and death, and a decrying of the damage we have done and continue to do to the precious world we have inherited. His way of seeing the world — where instinct and careful observation unite — is one to celebrate.

His simple request is that we “find heart” in the miracles, beauty and generosity that surround us.

I’ve always been in awe of the abundance the best poets promise and Bill Yake is no exception.

Note: Kudos to Empty Bowl Press for their splendid production; and, for Ormsby readers, here is the publisher’s bio:

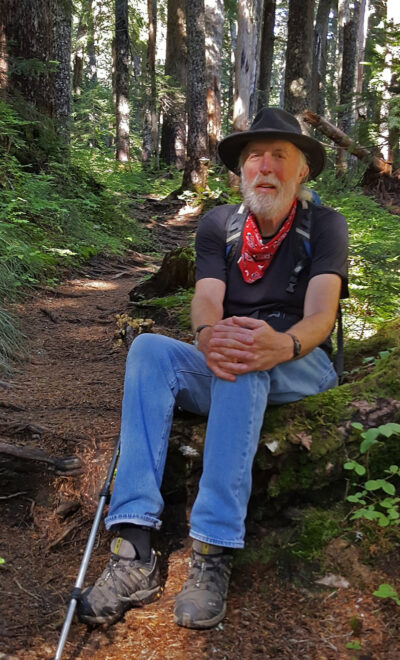

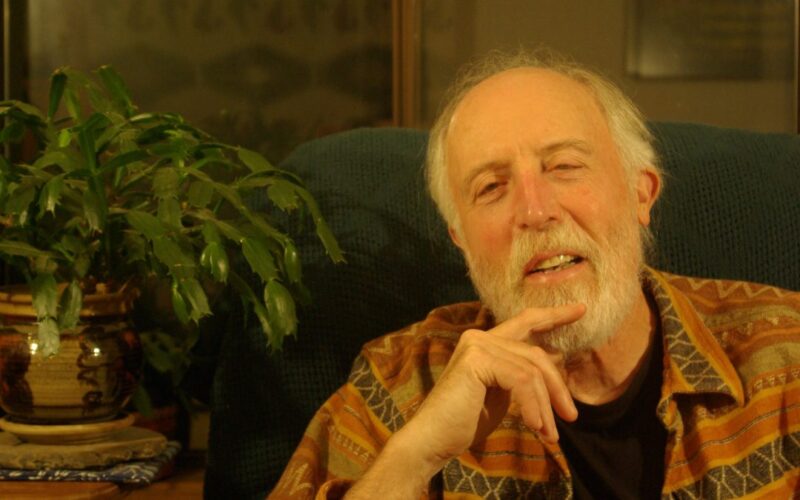

Long a resident of the Pacific Northwest, Bill Yake has made poems since the late 60s. There were years he worked lookouts, road construction, and cemeteries. He’s fought forest fires and run a sub-three-hour marathon. During his 25-year career with Washington State’s Department of Ecology as an environmental scientist and engineer, Bill diagnosed malfunctioning sewage treatment plants and tracked poisons in waters, fish, and sediments. He teamed with environmental trainees in Tunisia and authored the Washington State Dioxin Source Assessment…. Throughout, he has studied natural history, read abundantly, and thought hard about evolution and the place of humans in nature.

*

Ron Smith, born and raised in Vancouver, is the author and editor of numerous books, including the award-winning Elf the Eagle, The Defiant Mind: Living Inside a Stroke, and, most recently with Dr. Bernie Binns, Improbable Journeys: from Crossing the Himalayas on Horseback to a Career in Obstetrics and Gynaecology [editor’s note: reviewed here by May Q Wong and here by John Kenwright]. For close to forty years, Ron taught at universities in Canada, Italy, the US, and the UK. In 2002 he received an honorary doctorate from UBC and in 2005 he was the inaugural Fulbright Chair in Creative Writing at Arizona State University. In 2011 he was awarded the Gray Campbell Award for distinguished service to the BC publishing industry, primarily as the founder and publisher of Oolichan Books from 1974 to 2009. In 2021, Elf’s Family Tree, a sequel to his earlier illustrated children’s book, is forthcoming from Rock’s Mills Press. He lives with his wife, Patricia Jean Smith, also a writer, in Nanoose Bay on Vancouver Island.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1178 The intelligence of deer trails”

Yes. In awe. Read this book.

This is the kind of review this book of Bill Yake’s deserves.

What gets done with trails, in Yake’s poems, and in Ron Smith’s review, and bringing in of deer and Howard McCord intelligence, adds to what we take into the rest of our time here.