1173 Dandelions through asphalt

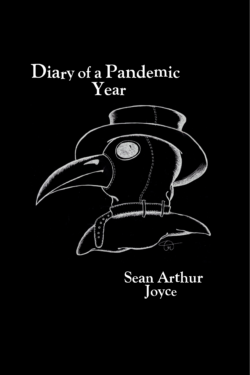

Diary of a Pandemic Year

by Art (Sean Arthur) Joyce

New Denver: Chameleon Fire Editions, 2021

$20.00 / 9780995240162

Reviewed by Roger C. Lewis

*

*

The day after Covid, surgical masks

lay dead in the gutters, so many leaves

riffled into history by the collective sighs

of billions – breathe O breathe free

at last!

So writes Joyce hopefully in poem No. 26 of this timely and topical book that does not disappoint. It alludes to experiences, emotions, thoughts and fears that all of us can identify with since the Covid horror befell us in March 2020. Watching with growing alarm as our friends grew distant and aggressive, we were warned by “experts” we could never shake hands again.

People cursed one another in public for not wearing masks or being too close. Police tackled women to the ground for letting their children play in the park. Men were fined thousands of dollars for walking their dogs. A pastor drove marauding “officials” out of his church when they tried to shut down an “illegal” service he was conducting. Drunkenness, suicides and drug overdoses went through the roof. Government made constant prophecies of new waves, worse viruses and total public health breakdowns. Nothing would ever be normal again. House arrest forever.

“Poetry,” declared the great poet Coleridge, “is the best words in the best order.” That challenging definition is one that poet Joyce would surely endorse and has illustrated in his latest work. While his title deliberately references Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, a prose account of London’s 1665 bubonic plague, Joyce has chosen to make his Diary out of what he calls “a poetic log of events” dating from March 2020. The poet goes behind and beyond mere descriptive narrative using a condensed and intensified language dominated by metaphor and other figurative expressions. Achieving universality of thought and broad appeal to the imagination by following prophetic, intuitive modes, these poems, as Joyce mentions in his Author’s Note, “render the spiritual essence of the scene depicted” (p. 1). Brilliant insights are sharpened by emotional intensity and vivid diction, underscored by the poet’s rich verbal music.

Consequently, these “diary entries” are not mundane mechanical prose but, truly, the best words in the best order.

The book has an interesting three-part structure. Part I, Diary of a Pandemic Year, consists of 26 titled poems, some with epigraphs, following a loosely-sketched chronology dating from March 2020 through various headline events such as the George Floyd riots, increasing lockdowns, crackdowns and restrictions, ending with “The Day After Covid.” Most poems in this section mention the terrors of isolation and confinement with recurring imagery of chains and prison. In sharp contrast are the 20 poems of Part II, Odes to Earth, that emphasize communion and celebrate our closeness to Nature including not only other humans but birds, animals and insects. A rufous hummingbird briefly hovering outside a window is “three grams of beaming welcome” (p. 57). Part III, Songs for the Lost, is a series of elegiac poems, mostly for family members, including the poet’s mother, whom he has recently lost (though not from Covid). But it is also intended to eulogize those killed by the pandemic, especially the very vulnerable elderly whose high casualty rate raises questions about our society’s evident loss of respect for seniors.

In literature, plague tends to appear as a metaphor of retribution: divine, extraterrestrial, environmental or political. Biblical plagues, particularly those sent against Egypt in Exodus, have inspired writers to compose variations on the theme of a proud empire brought to its knees by an angry Deity. Joyce strikes this note in the opening poems of Part 1: “slick prophets in silk suits” squeal about our sins into “God’s angry megaphone, ” (p. 7) fear making the streets in desolate cities as empty as they were in Defoe’s Journal. The Egyptian slavemasters were annihilated by plagues that passed over the Israelites but the Feast of the Passover is celebrated as a lesson not so much to the Pharaoh as to the Jews (Passover, April 2020). But against this imagery of apocalyptic punishment and a barren wasteland of sterility the poet sets over a mythical construct of what Northrop Frye called “the assumption of total coherence,” transcendence that banishes doom and gloom. There is a recurrent image in Part I of dandelions breaking through a fractured crust of concrete or asphalt, splitting open pavement meant to crush them, the human spirit rising to “carpet a dead field with new sunlight” (see poems No. 5 and 22). Cynicism and despair caused by the plague’s effects are counteracted by the hope in poem No. 21 (“to all the architects of lockdown”) that when Earth reawakens “all those/whose animal love for the world/remains alive will smash the locks,/dance on your forgotten ashes/and sing the songs/of Creation reborn.” If fertility is to be restored, rituals of purification must be enacted.

Deliverance from the squalor of the plague may come from a reconnection with Nature, as suggested in Part II, Odes To Earth. These poems display an Emily-Dickinson-like ability to capture the essence of wild creatures and natural organisms through appealing to our imaginations. There is a return to the tone of Part I in Dark Mountain (p. 75), an autumnal prayer to protect the poet against the terrors of the forbidding mountain environment. Part III is the most personal part of the book, although it is connected with the theme of the cruel and unusual ban on honouring the dead during the pandemic. Little Eyes, for his recently-deceased mother Diane, has an epigraph associating it with John Lennon’s primal, heart-wrenching song Mother, baring the painful memories of a small child pathetically expecting from his troubled mother “a future/ she can never provide,” while here trying to soften them in retrospect. Moth Fairy is a moving eulogy for a beloved village character:

How many candles must we light

To match the stars in her eyes? (p. 97).

Epidemic disease can symbolize our own deepest fears. A strong sense of evil and intense awe in the face of death leads us to what Susan Sontag has called an “imaginative complicity with disaster” in which, lacking religious or philosophical resources to talk intelligently about evil and death, we fall back on myth-making. We imagine some apocalyptic plague to deliver us from our failures. Thus, as Camus notes at the end of The Plague, the bacillus never dies or disappears for good:

Perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men,

it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.

The book itself is remarkably beautiful. Designed by the poet, it contains numerous illustrations by him, including a mediaeval plague doctor’s mask on the cover. Printed in fine letterpress on laid paper, it was flawlessly copy edited by Anne Champagne. It is available from the author at his website.

*

Roger C. Lewis is Professor of English Literature (Emeritus) at Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada. Dr. Lewis is the author of many books, articles and reviews. He was Co-Editor of the 10 Vol. Edition of The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (2002-2015), Editor of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The House of Life: A Variorum Edition, and Editor of The Collected Poems of Robert Louis Stevenson. He wrote Poems and Drawings of Elizabeth Siddal and Thomas James Wise and the Trial Book Fallacy. He also taught English Literature at the University of Toronto, Ryerson University, and Athabasca University. He specialized in research on and teaching of poetry and Comparative Literature. Recently he published a collection of short stories called Identity Matters: Canadian Stories. He lives with his wife Nancy and works in Silverton, where he visits frequently with his sons Scott and Cameron and their families. Editor’s note: previously Roger Lewis reviewed Dead Crow & the Spirit Engine (also by Art Joyce, 2020) for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1173 Dandelions through asphalt”