1124 “The Noise of Time” and the Removal of History?

ESSAY: “The Noise of Time”[1] and the Removal of History?

by Robin Fisher

*

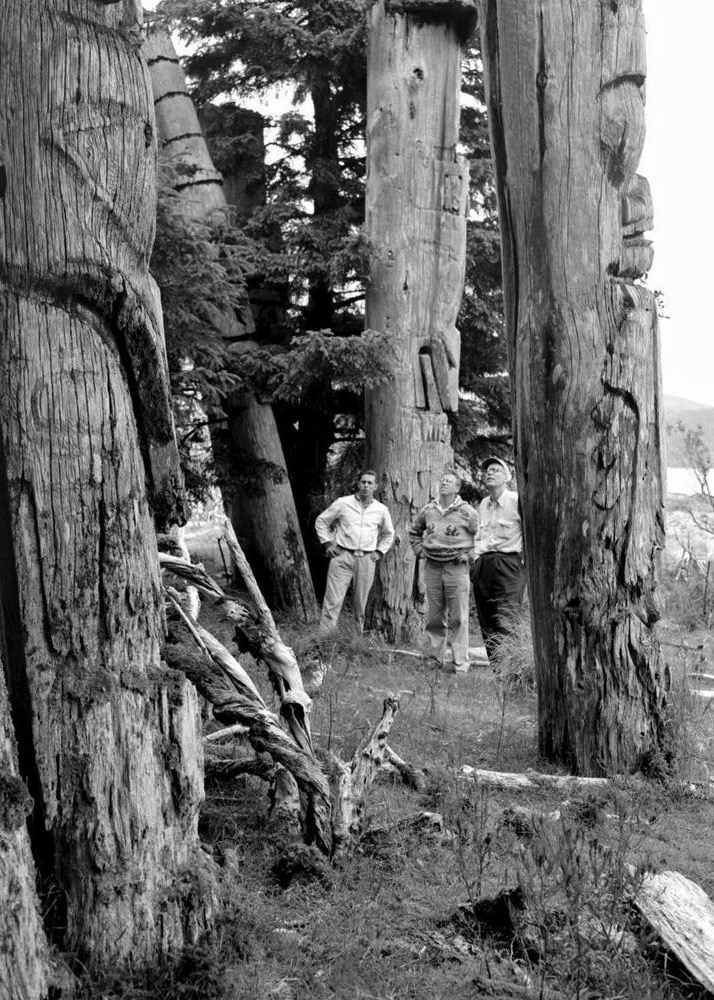

In 1957 a group of anthropologists went ashore at SG̱ang Gwaay, which they knew as Ninstints, the site of a long deserted Haida village on Anthony Island. With ropes, pulleys and crosscut saws they lowered a few of the surviving totem poles to the ground, crated them up and floated them out of the cove behind a seiner boat. They were then lifted on to a Canadian Navy vessel to be taken for restoration and display at the Provincial Museum and the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology. When the expedition left, many totem poles remained to be engulfed by the forest and decay into the ground. Sixty years later, in Victoria and New Westminster, city workers with cranes and jackhammers lowered statues of John A. Macdonald and Matthew Baillie Begbie and took them away on flatbed trucks. The statues were carted off to a storage facility. At least in New Westminster, they left behind a small pile of rubble. What do these two moments in the history of the province, separated by a couple of generations, tell us about myth and memory and the value of history?

I grew up with monuments to memory. New Zealand/Aeotearoa is, even more than Canada, a country of war memorials.[2] There is one in every town, big and small, and some even stand on rural crossroads where there is no town. My family built a few of them and we were raised in the knowledge of their complex meanings. One of my grandfathers referred all his life to “my brother who was killed in the war.” He was killed in the battle of the Somme in the First World War and he lies in a small cemetery, along with a few graves of German soldiers, in a farmer’s field in northern France. My other grandfather was severely injured on the Somme at about the same time as my great uncle was killed. He survived, and by the Second World War was a Lieutenant-Colonel in charge of the New Zealand troops on Norfolk Island. I have a childhood memory of the portrait of Winston Churchill with some lines from his “we shall never surrender” speech in my grandfather’s front hall. My father was part of another New Zealand tradition. He was a Christian pacifist who believed that there was no such thing as a just war. He really wondered about war memorials, particularly those on the walls of his church. Within my family there were divergent views, that were shared and debated, about what war and its memorials signified.

In the central square of my home town, as well as a cenotaph, there is a statue of the Maori leader Te Peeti Te Awe Awe sculptured of white Carrara marble in the European style. Maori and Pakeha alike remember Te Awe Awe for making alliances with the newcomers, mitigating their impact on his people and maintaining Maori traditions.[3] Whenever I return to my home town I stop by and say, in the few words of te reo (Māori) that I still remember, kei te pēhea koe, how are you? As a child, the town square in Palmerston North was a place of green, of trees and a pond surrounded by rushes where the mallards nested. More recently the city council renovates the square about every five years and now it a place of concrete and steel. The ducks sit forlornly on the concrete nib around the pond. As Joni Mitchell put it, “they paved paradise/ And put up a parking lot.” Yet Te Awe Awe endures as a symbol of what we might now call reconciliation. There was a proposal to relocate him during one of the renovations but a public outcry stopped it. So Te Awe Awe still stands, with a mere (war club) clutched to his heart, keeping an eye on the shoppers as they go in and out of the mall across the street.

One historian, who has written about memory, draws a distinction between representations of official, public memory and expressions of personal, or vernacular, memory.[4] They are different memorials to different historical memories. A few kilometres from the centre of my hometown, on what used to be the outskirts of the city, stands another, less celebrated but more personal, memorial. An obelisk of red granite, it is the tallest in the old cemetery. As you approach it you can see that it is emblazoned with one name — “Fisher.” Memorials, as the word indicates, are about memory. The Fisher monument is in memory of several generations of my family and to those forebears who worked on the cathedrals of Britain before immigrating to New Zealand and supplying three generations of monumental stonemasons. My father, the last of the line of masons, insisted that I could do anything with my life except come into the family business. He knew the importance of education and had a sense of wider possibilities. So I became a student of history, the meaning of the past and the importance of memory. One aspect of the historian’s discipline is to learn to distrust, or at least to question, memory. For memory, whether public or personal, is as much about forgetting as it is about remembering.

When I came to British Columbia, after learning and writing about Maori/pakeha history in New Zealand, I was stunned at the absence of Indigenous people from the historical writing on this province. There were exceptions like Wilson Duff’s Indian History of British Columbia, but the silence of historians was deafening. With the supervision of Wilson Duff and the help of others, I tried to make a contribution to changing the received view of British Columbia history and the role of First Nations people.[5] My second supervisor, Margaret Ormsby, was not always happy with my conclusions particularly about colonial figures like Joseph Trutch who led an assault on First Nations lands and cultures. Other colleagues thought better of my efforts when, to my amazement, my first book as an historian was awarded the John A. Macdonald prize in Canadian history. As a memory of that honour I have, as I write, a heavy bronze paperweight on my desk with an image of a rather spindly John A. Macdonald with his hand resting on a large volume. His head is cocked to one side and, in my imagination, he is looking quizzically at the country that he made and what we have made of him.

As a newcomer, I also found very few statues of First Nations people in British Columbia, at least of the European kind. There is at least one exception to prove that rule, in Nanaimo not far from the iconic bastion. It is a bust of Ki-et-sa-Kun who looks across a small plaza at the matching bust of Mark Bate, the first mayor of Nanaimo. An inscription below Ki-et-sa-Kun asks us to remember him because he showed the Hudson’s Bay Company where to find coal in the area. In Lytton there is a European style memorial to the Nlaka’pamux leader Cexpe’nthlEm, known to the newcomers as David Spintlum. It is a simple cross and not a likeness. It was originally erected by the Nlaka’pamux, but both the memorial and Cexpe’nthlEm have been increasingly recognised by non-Indigenous people over the years. The chief is remembered, particularly by the colonizers, for negotiating a peaceful settlement to conflict between miners and Indigenous people during the Fraser River gold rush of 1858. At both ends of the Pacific, in New Zealand and British Columbia, settler societies tend to erect statues and memorialise Indigenous leaders who co-operated with the newcomers.

Of course, most First Nations in British Columbia have no need of statues made of marble or granite because they have their own forms of memorial though, being carved in cedar, they are less durable than stone. While they are usually called totem poles, anthropologists came to refer to them as monumental sculptures. Like statues, totem poles are, at one level, markers of memory. Some were explicitly memorial poles with boxes at the top that contained the remains of high-ranking individuals. Totem poles also stood in place as statements of the peoples’ ownership of the land. They were testament to the wealth of the owner and expressions of the imagination and skill of the carver. By the 1950s there were precious few totem poles left in British Columbia: either in the villages because they had decayed away, or in the province’s museums, because most of the poles that had been salvaged were taken to museums in other countries.

Those who came to Ninstints in 1957 to recover totem poles were a who’s who of Northwest Coast Anthropology at the time. The group was organized and led by Wilson Duff who was Provincial Anthropologist at the Museum of Natural History and Anthropology in Victoria. He would later become a faculty member in Anthropology at the University of British Columbia. Harry Hawthorn was the founder and Head of Anthropology at UBC. Wayne Suttles, also at UBC, was a leading authority on the Coast Salish. Michael Kew, Wilson’s colleague at the Provincial Museum, was at the beginning of a long academic career studying Northwest Coast Indigenous cultures. None of these were First Nations people, but they were all deeply committed to learning about the cultures of the Indigenous people of the province and to developing a conversation based on understanding between Indians and newcomers at a time when that conversation was falling on deaf ears. They were accompanied on the trip to SG̱ang Gwaay by Bill Reid, who was yet to become the preeminent Haida artist of his generation, and at that point was working for the CBC. He was there to record the poles and the work to recover some of them. The group travelled from Skidegate to SG̱ang Gwaay on a seiner boat with a skipper, Roy Jones, and crew who were all Haida.

Wilson Duff was well aware of the history of collectors removing totem poles from Northwest Coast villages without the permission of the owners, a.k.a. theft. He was determined not to repeat that history. The few remaining inhabitants of SG̱ang Gwaay had moved to Skidegate seventy years earlier and so establishing ownership of the totem poles at the deserted village was difficult both for Wilson Duff and the Haida descendants. Duff held a series of meetings over a couple of years with the Skidegate Band Council to get approval to remove some poles and try to establish who owned them. At one point a Victoria newspaper jumped the gun and, in a report on the effort to salvage a few SG̱ang Gwaay poles, gave the impression that some had already been removed. Duff immediately wrote to the Band Council members to reassure them that no poles would be taken without permission and to arrange further meetings to discuss the issue. He wrote sensitive replies to Haida people who claimed ownership of poles and asked for their help and advice with the process. He had Peter Kelly, the Haida political leader, join him in the discussions with the community. Peter Kelly’s mother had been married to Tom Price, the last individual to bear the Ninstints name as the chief of the village. Duff wrote a letter in the Native Voice, the newspaper that served First Nations communities and interests, to explain the importance of preserving some examples of totem pole art and seeking any advice that anyone could offer on how to legitimately carry out the salvage.[6]

Another complication was that Ninstints had never been designated as an Indian Reserve. Federal law required the permission of the Department of Indian Affairs before a totem pole was removed from an Indian reserve. But because Ninstints was not a reserve Indian Affairs officials argued that Duff did not have to have the permission of the Haida. He responded instantly that while there may not be a legal obligation, there absolutely was a moral one. He then used his influence in Victoria to have Ninstinsts declared a Provincial Park to give it a measure of protection. Years later SG̱ang Gwaay would be declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

When all was said and done, neither Wilson Duff nor the Skidegate Band Council could firmly establish who were the owners of specific poles at Ninstints. The Band Council gave permission to salvage some poles while they continued to discuss who might own them. Payment for the poles was made to the Band Council rather than individual Band members. In the meantime, the anthropologists, accompanied by Bill Reid and some members of the Skidegate Band, went to Anthony Island to recover a few of the totem poles.

Landing at Ninstints in 1957, Wilson Duff and his colleagues were deeply affected by what they saw and felt. The village site of SG̱ang Gwaay is located on a sheltered reach of water protected by a rocky islet in front of it. As they rounded the corner and landed on the stony beach there were the totem poles standing or leaning, silver grey against the dark green of the forest that was growing to engulf them. Most were too far gone with decay to be salvaged. Wilson Duff was moved by the spirits of those that had once lived there and the vibrant culture that was now lost. He and Bill Reid connected with, and reflected on, the imaginations of the artists who had carved the poles. The echo of the past, of history and memory, was real. Wilson Duff would reflect on that experience for the rest of his life and later wrote that: “What was destroyed was one more bright tile in the complicated and wonderful mosaic of man’s achievement on earth. Mankind is the loser. We are the losers.”[7] It was, therefore, important to preserve at least a vestige of what remained and time was of the essence.

While they were moved by the place and its past, the process that they followed to recover some of the totem poles was not elegant. The totem poles were secured with ropes and pulleys so that when they were cut through at the base they could be lowered to the ground with a minimum of damage. Some had to be disentangled from the tress that were growing around and sometimes through them. Once lowered to a bed of cedar boughs they were crated up, sometimes in sections, floated out to waiting boats and shipped to museums in the south. Half went to the Provincial Museum in Victoria and half to the UBC Museum of Anthropology. Both institutions put them in storage facilities while they planned new buildings. Wilson Duff was so unimpressed with the storage shed at UBC that he dubbed it “the pole vault.” In a few years, though, the recovered poles would have pride of place in new museum buildings when they were completed in 1968 in Victoria and 1976 at UBC.

The removal of the SG̱ang Gwaay totem poles only became controversial in some quarters after the fact. As views of the past changed, different judgements were made. There were false reconstructions of the past process of removal by scholars who were selective in their use of evidence.[8] More valid points were made by both First Nations people and newcomers. They reminded us that totem poles were supposed be left to decay into the ground from whence they came. Some members of the 1957 expedition to SG̱ang Gwaay had second thoughts many years later about taking the poles. Wilson Duff and Bill Reid never did have regrets.[9] They recognised that most totem poles would fall to the earth but believed that a few examples of the ancient art should be preserved. That the record of the artistic imagination of a once vibrant culture should not be obliterated, but stand for all to see. Surely there is value in preserving that memory. Certainly, some Haida artists think so. Robert Davidson has told us that, as well as being able to study the lines and the forms created by earlier generations of carvers, the ancient poles enabled him to appreciate the effects of weathering and take it into account when he carved new totem poles. In 1969 he used that old knowledge to carve and raise a totem pole in Masset. It was the first new pole to be raised on Haida Gwaii in more than a generation.[10] One could say that the ancient poles were lowered so that new ones could rise.

When Wilson Duff and his colleagues left there were still totem poles standing along the shore facing the water at SG̱ang Gwaay. A few, leaning and falling, remain today: silent reminders of a world that is lost. But soon even they will be gone while only the spirits of the people who lived there remain. Then the only physical monuments to a generation of Haida artists will be those in the museums.

*

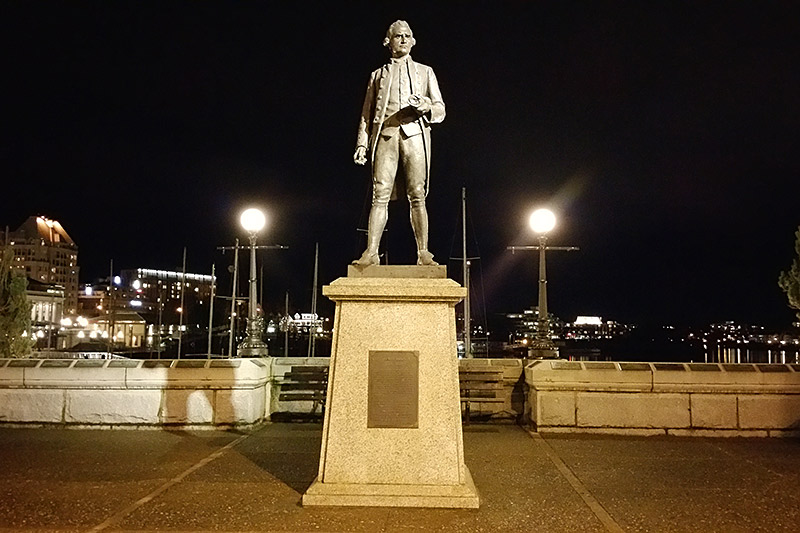

More recently, in 2018 and 2019, we saw the removal of another kind of memorial: of Macdonald and Begbie who played founding roles in the establishment of the nation of Canada and the Province of British Columbia. Statues are made of stone and, unlike totem poles, are meant to last. The interpretation of them, however, seldom endures without re-evaluation. Macdonald, Begbie, and their statues have also come to represent some of the worst aspects of the history of settler impact on Indigenous people. These statues were removed with much less consultation than by the anthropologists sixty years earlier. Both statues were removed at the behest of First Nations groups, the Lekwungen and the Tsilhqot’in, for whom Macdonald and Begbie represented tragic experiences in the history of colonization. The cities of Victoria and New Westminster seemed to make every effort to avoid discussion with those for whom the statues represented a different history. Discussion was largely limited to the Council chamber. If the decision in Victoria were predetermined in the interests of reconciliation, then the city authorities were wise not to throw the issue open to public discussion since polls showed that a majority opposed the removal of Macdonald. The mayor later apologised for not consulting more widely.[11] After the City Council vote in New Westminster, Begbie was taken down before a small group supporting the move on a Saturday morning so that the proponents would not have to face the response of those who objected to the removal. Now that the deed is done, when hindsight is perhaps an advantage, these removals deserve some more thought.

One perspective on the removal of statues and totem poles is to think about the distinction between history and historical memory. History as practiced by historians is, of course, a conversation between past and present. Therefore, interpretations change with time and generations. At the same time, history is about understanding the past based on listening to the voices of those who went before. It is about exploring the complexity of individual lives and the nature of social change. And it is about description and interpretation based on the evaluation of the evidence and counter evidence surviving from the past. So trying to understand history, in my experience, requires sheer hard work. For it demands that some deference be paid to the past and the need to understand it as it was. Without history, as the post-colonial theorist Homi Bhabba reminds us, “Nations,” and I daresay provinces, “like narratives, lose their origins in the myths of time and only fully realise their horizons in the mind’s eye.”[12] Knowing the past calls for imagination but it is grounded in evidence. And for the historian, history is more than just going into the shopping mall of the past and selecting items off the shelves that are suitable to serve the present.

Historical memory, on the other hand, is a public commodity that is more attuned to the present than the past. Historical memory calls upon the past to serve the needs and interests of various individuals and groups in the present. It is an individual or, more likely, a social construct. The evidence of history exists. Historical memory is created.

History interrogates the past in an effort to understand patterns, cause and effect and mixed motives. Historical memory captures events and individuals from the past ahistorically, reconfigures them based on partial evidence and puts them on public display in the present. It often relies on the historical fallacy of presentism, that is judging the past and people of the past by today’s standards. Nothing is easier than to find a person from the past wanting according to values that were not current, or only held by very few, when they were alive. Thus, if, as one historian has observed, “history is the enemy of memory,” then the reverse is also true and memory is the enemy of history.[13]

The statue of John A. Macdonald was removed from the entrance to City Hall in Victoria because some people remembered that he was an advocate of residential schools in Canada. Schools that were traumatic, damaging and fatal for so many young First Nations people. A year earlier, in another context, residential schools were remembered with the raising of the Haida artist, James Hart’s reconciliation totem pole on the University of British Columbia campus. It included thousands of nails hammered in by people who survived residential schools in memory of those who did not. At the top of the totem pole is an eagle representing power and a direction forward. Public reminders of terrible episodes in our history are important “lest we forget.”

In Victoria it was painful for Indigenous people, remembering a history that is ugly and real in their lives, to pass by the statue of Macdonald as they entered the hall of city government. City officials, including the Mayor, repeatedly stated that Macdonald was the “key architect” of residential schools. In Montreal, when demonstrators cut down and decapitated a Macdonald statue, he was described as the “creator” of residential schools in Canada.[14] The first Residential School in what became Canada was established by the Recollect Order in New France in 1620, more than 200 years before Macdonald entered politics.[15] Still, there is no doubt that Macdonald was a proponent of residential schools as a way of dismantling First Nations cultures in the interest of absorbing those who survived into settler society.

An accomplished historian, who has spent a lifetime learning, thinking and writing about the relations between Indigenous people and newcomers, has recently published an account of “John A. Macdonald and the Indians” that describes the good, the bad and the ugly. Macdonald was the most important figure in the making of Indian policy from 1867 to 1891 and his legacy “is both very complex and very large.” In addition to residential schools, he oversaw the egregious pass system to restrict movement of Indian people and deliberately used starvation as a means of convincing them to locate on reserves. The rigorous repression of Prairie Indians after the conflict in the North West in 1885 was “totally reprehensible” and the execution of Louis Riel a “colossal error.” At the same time, Macdonald did understand First Nations’ prior ownership of the land and the need for treaties with governments, a principle largely ignored in British Columbia. He also gave the right to vote to adult male Indians who owned property in central Canada, seventy-five years before all First Nations got the franchise in 1960.[16]

For all Macdonald’s influence, Indians and Indian policy was not often at the top of his mind throughout his long political career. So it would be more accurate to describe Macdonald as the architect of Canada. He was a leader in the politics of unification and federation that first brought Upper and Lower Canada (Quebec and Ontario) together and then led to the establishment of the Canadian Confederation in 1867. Macdonald was Canada’s first Prime Minister and was successful in shepherding other parts of Canada, including British Columbia, into the fold and taking steps to secure the nation against the threat of American encroachment. These were not small achievements.

The Matthew Baillie Begbie statue was removed from outside the New Westminster Court house because some people remembered the role that he played in the hanging of five Tsilhqot’in leaders following a burst of violence against settlers encroaching on their territory in 1864. The attacks on a road building party and then a group of settlers are now called warfare by the Tsilhqot’in. At the time, the settlers called it an insurrection and the action drove the colonists into a frenzy of rage. The alleged leaders of the attacks were misled into surrendering to colonial officials, tried in Begbie’s court, convicted of murder and, after the sentences were confirmed by the Legislative Council, five were hanged in Quesnel. Later two more Tsilhqot’in were tried, though not by Begbie, and one hanged in New Westminster.

It could be argued that these Tsilhqot’in were the victims of British law rather than Matthew Begbie, though Begbie was the representative of that law. Begbie was the first Chief Justice of British Columbia and, along with Governor James Douglas, played a major role in preventing an American takeover of the Colony during the Fraser River gold rush in 1858. It is hard to imagine that First Nations people would have been better off if British Columbia had become a part of the United States given the genocidal wars that were being waged against them in Washington Territory. Begbie, unlike most colonists, took an interest in First Nations cultures and was sympathetic to their plight. He learned the polyglot trade language, Chinook Wawa, and some other Indigenous languages in an effort to communicate. He advocated for their land claims. When First Nations people appeared in his court he often gave them the benefit of the doubt. He allowed their testimony even though they could not swear on the bible and he convicted newcomers of crimes against First Nations people on the basis of that testimony. When the Federal Government passed a law banning the Potlatch in 1885 and accused were brought before him, he refused to convict them on the grounds that the law was not written with sufficient clarity. The statues of Macdonald and Begbie were removed because the historical memory of some aspects of their life’s work overrides the history of their overall contribution.

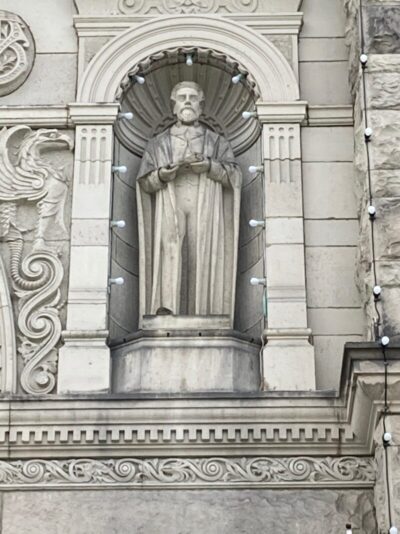

Historical memory is selective about those that it decides to remove from our sight. So who is next? One wonders about James Cook, the most brilliant navigator of all time, who still stands, inappropriately with his back to the sea, in Victoria. Some of his statues have been removed in New Zealand as Aeotearoa approached the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of his arrival on its shores. George Vancouver, who put British Columbia on the map and laid it open to exploitation, still stands in front of Vancouver City Hall but not unscathed as his statue was recently vandalised. He is presumably more secure atop the Legislative Assembly in Victoria. The Spanish navigator, Bodega y Quadra, who shared the circumnavigation of Vancouver Island with Vancouver, is not so well remembered. He is tucked away in a leafy garden a couple of blocks down from the Legislature where out of sight is out of mind. But are Matthew Begbie and James Douglas, the colonial founders of British Columbia, unassailable as they stand in their niches on either side of the entrance to the legislative building? Or Simon Fraser on the boardwalk in New Westminster? The list could go on. And statue removal is easy when groups rely on historical memory and do not feel the need to discuss the matter with those who place more value on history.

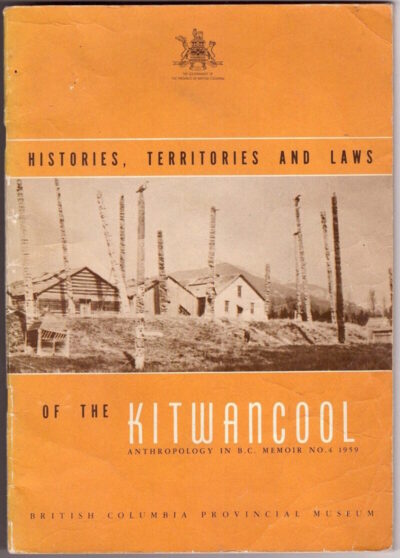

In 1957 Wilson Duff wanted to save and restore the totem poles of SG̱ang Gwaay as a way of preserving the history and the art of the people who made them. The poles in the museums, the stories that the anthropologists heard from the Haida elders, and the written accounts of the culture and life at of SG̱ang Gwaay when it was a living community record that history for us all.[17] Wilson Duff learned from the experience at SG̱ang Gwaay and refined his approach in other Indigenous communities. A few years later, when he recovered four poles from the Gitksan village of Kitwancool (Gitanyow), he first negotiated a signed contract with the elders of the community that not only provided for replicas to be made of the poles and returned to be raised in the community, but also for the history of the Kitwancool, as told by the elders, to be recorded, published and used in university classrooms. That history endures to today in Histories, Territories and Laws of the Kitwancool.[18]

Removing the statues does not, in itself, preserve any history, either Indigenous or newcomer. The History Department at the University of Victoria made a valiant effort to introduce history into the debate by running a series of public presentations on the lives of colonial figures like Macdonald and Begbie. But the statue removers were not particularly interested. They frequently told us that they were not removing history. But if history teaches us one thing, it is that people and the past are seldom understood through simple, one-dimensional explanations. One life, and all the lives that make up history, are full of complexity. To reduce them to a simplification denies our humanity and the history that lives make. Simplification is the removal of history.

The removal of history is confirmed if there is no follow up to the removal of totem poles or statues. After he recovered some totem poles from SG̱ang Gwaay and Gitanyow, Wilson Duff spent the next twenty years of his life striving to understand the First Nations cultures of British Columbia and communicate what he learned to a largely tone-deaf settler population. He curated ground breaking exhibitions of First Nations art, he gave testimony as an expert witness in two land claims cases that turned British Columbia history on its head and, at UBC, he taught a very popular course giving hundreds of students lessons in the cultures, and the predicament, of First Nations people in this province.

Following the removal of Macdonald’s statue the city of Victoria has held dialogues on reconciliation which is an important first step down that long road. The “dialogue” on John A. Macdonald, however, presented only one view of him: as a villain. The heartfelt anguish about his terrible record on First Nations matters was important to hear. But no one spoke to his record as a nation builder.[19] Captured by certainty, those who seek to set the historical record straight seldom face up to their own biases. The mayor of Victoria frequently calls on us to understand the complexity of history, but replacing one one-sided view of an historical figure with another is just flipping the coin, not appreciating complexity. And it is compounded by the historical error of judging the past only by the standards of the present. Mind you, what can one say when even Canada’s historians preferred historical memory over history when, as a group, they removed John A. Macdonald’s name from the Canadian Historical Association’s annual book prize.

Along with removing the Begbie statue, the New Westminster City Council included a section on reconciliation in its strategic plan and hired a consultant to map out a process to move the reconciliation agenda forward. It will take time to make progress. At the same time, a Council member presented a motion to take a “deep dive” into New Westminster history so that City Councillors and staff could better understand colonialism and the history of residential schools. There was no mention of any historians being involved or of perhaps taking another look at Begbie’s overall record of dealings with First Nations people. Apparently unmoved by hired consultants or City Councillors performing deep dives, the First Nations man still stands at the entrance to the New Westminster Skytrain station offering perceptive insights in the hope of remuneration. I wonder if anyone from the City has spoken to him about the meaning of truth and reconciliation.

Beyond a moment of controversy and removal there is no enduring educational or awareness value in taking down these statues unless there is follow up to make real change. What have the City Councils of Victoria and New Westminster done since they removed the statues to improve the lives of the Indigenous people that live in and around their community? Or is statue removal merely a moment of acknowledgement to historical memory followed by more neglect? As a society we have got better at the easier stuff of reconciliation such as statue removal and apologies. The hard work of improving people’s lives has a long way to go. And how will we be remembered in a hundred years if we engaged in the superficiality of statue removal but did little to change the conditions that, for many, they had come to represent?

Wilson Duff and the anthropologists recovered totem poles only after careful consultation with Haida people in Skidegate, in the case of SG̱ang Gwaay, and the owners of the poles at Gitanyow. Salvaging the totem poles was part of an effort to record and preserve the history and culture that they represented. Their example was not followed by the more recent statue removers who chose to have a wider discussion only after the statues were lowered. That may be partly because the history of consultation and then recovery of the totem poles has been turned, in historical memory, into a colonialist outrage carried out with little or no consultation with the owners. We might well ask who owns the statues of Macdonald and Begbie, whose history do they represent, and who was consulted? Beyond noting that the statues are owned by the two cities, though in New Westminster there is some doubt about even that, the answer is that they have come to represent different histories. For First Nations people they personify colonial oppression and for many of the newcomers they were builders of a new nation and its Pacific province. The statues were removed after consultation with the first group, but not the second group of “owners.” Historical memory has been served but has history been done a disservice? Are we going down a road that ends with history, what actually happened in the past, being irrelevant? All that matters is what we think of it today.

We can safely say that interpretations of both history and historical memories will continue to change through the noise of time. As totem poles return to the earth and statues come and go, it is important that we do not lose sight of the distinction between history and historical memory. For if we do the past will become, not just a foreign country as one historian has put it, but another planet.[20] In the short term at least, there have been some aspects of history and memory, such as Canadian involvement in two world wars, that, in spite some wavering, have not disappeared.[21] For all of the changes in historical memory, I have seldom heard a call, even from my pacifist father, for the removal of a war memorial. That is partly because history and historical memory have one thing in common: a good understanding of each requires real effort to appreciate the views of others. It is also a prerequisite for reconciliation.

*

Robin Fisher returned to the coast after holding administrative positions and teaching in universities north and east. Earlier in his career as an historian at Simon Fraser University he published on the history of British Columbia, the Pacific, and New Zealand. His books include Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890 (UBC Press, 1977; second edition, 1992) and Duff Pattullo of British Columbia (University of Toronto Press, 1991). He has now written a biography, Wilson Duff: Coming Back, that is forthcoming with Harbour Publishing. Editor’s note: Robin Fisher has reviewed books by William Frame & Laura Walker and Michael Layland for The Ormsby Review.

*

Endnotes:

[1] The phrase is taken from Julian Barnes, The Noise of Time (Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada [Vintage Canada], 2017), in which the author writes about a time when art was determined by politics.

[2] See Jock Phillips, To the Memory: New Zealand War Memorials (Nelson: Potton & Burton, 2016).

[3] Mason Durie and Meihana Durie, “Rangitane – 19th century: war, settlement and leadership,” Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/rangitane/page-2.

[4] John Bodnar, Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), pp. 14-15.

[5] Wilson Duff, The Indian History of British Columbia; Volume 1 The Impact of the White Man, Anthropology in British Columbia Memoir no. 5 (Victoria: Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology); Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1980 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1977).

[6] The Native Voice, February 1954.

[7] Wilson Duff and Michael Kew, “Anthony Island, A Home of the Haidas,” Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology Report for the Year 1957 (Victoria: Provincial Museum, 1957), p. 63.

[8] Ronald W. Hawker, Tales of Ghosts: First Nations Art in British Columbia, 1922-61 (Vancouver and Toronto: UBC Press, 2003) pp. 152-154.

[9] Kew, Michael, “Reflections on Anthropology at the University of British Columbia,” BC Studies, no.193, Spring 2017, pp. 163-185; interview with Martine Reid, 16 December 2014.

[10] Robert Davidson, Four Decades: An Innocent Gesture (Vancouver: Robert Davidson, 2009); interview with Robert Davidson, 14 January 2014.

[11] City News 1130, 6 September 2018, https://www.citynews1130.com/2018/09/06/john-a-macdonald-statue-removal/; Victoria Times Colonist, 29 August 2018.

[12] Homi K. Bhabba (ed.), Nation and Narration (London and New York: Routledge, 1990), p. 1.

[13] Richard White, Remembering Ahanagran: Storytelling in a Family’s Past (New York: Hill & Wang, 1998), p. 4.

[14] Vancouver Sun, 9 August 2019.

[15] J.R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 1996), p. 39.

[16] Donald B. Smith, Seen But Not Seen: Influential Canadians and the First Nations from the 1840s to Today (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 2021), pp. 3-38.

[17] See for example, Wilson Duff and Michael Kew, “Anthony Island, A Home of the Haidas,” Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology Report for the Year 1957 (Victoria: Provincial Museum, 1957).

[18] Wilson Duff (ed.), Histories, Territories and Laws of the Kitwancool, Anthropology in British Columbia Memoir no. 4 (Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Museum, 1959).

[19] https://www.victoria.ca/EN/main/city/witness-reconciliation-program/victoria-reconciliation-dialogues.html

[20] David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

[21] For an account of Canada’s changing memory and history of the Second World War see Tim Cook, The Fight for History: 75 Years of Forgetting, Remembering, and Remaking Canada’s Second World War (Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada [Allen Lane], 2020).

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

11 comments on “1124 “The Noise of Time” and the Removal of History?”

Wow! What a thorough article. You pose good hard questions about society, and fairness. I hope we can learn from this.

Thank you.

Why do I feel that there is a conflation here — of monuments and of history? Do white people have ‘history,’ while Indigenous peoples only have ‘historical memory’?

Perhaps the current critique of John A can balance out the century of glorification? He was the architect of the Residential School *system* — as in the systematic effort to assimilation Indigenous peoples…

I see I bought my own copy of Contact and Conflict in 1979 (because I wrote that in pencil) at the UBC book store (because the price tag is still on the taped-up dust jacket). I have returned to the book many times over the years. It created a stir among my profs in the Anthropology Department at the time. Wendy Wickwire’s At the Bridge is likewise a powerful book about unfair, unequal relations between settlers and first nations.

Thank you Robin for your deeply thoughtful, and wise, reflection. If any single piece stands to refute the claim of The Ormsby Review’s irrelevance (see TOR #1102) this is it.

Along with the rush to judgement, there’s the rush to erase — as if that will create truth and understanding. Instead, it creates a collective amnesia. Add artwork or interpretation to monuments, don’t remove them.

You give us much to ponder and question, within our cultures and within ourselves.

Thank you for writing this balanced and wise article on history and historical memory.