1103 A graphic memoir of endurance

Dear Scarlet: The Story of My Postpartum Depression

by Teresa Wong

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019

$19.95 / 9781551527659

Reviewed by Claire Sicherman

*

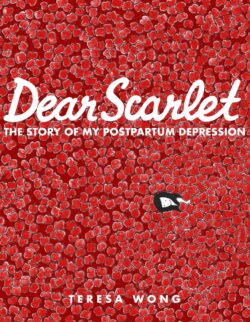

When I first held a copy of Teresa Wong’s Dear Scarlet: The Story of my Postpartum Depression, I fell in love with the cover. On it, an image of a woman’s face, the rest of her body buried deep in layers of what I first thought were hearts, but on closer inspection, are red apples. I was curious about the significance of the fruit, and would later learn, after reading the book, that Wong had a recurring dream which took place at a grocery store, where she’d climb into a bin and feel apples falling on her like rain. Wong says that with Postpartum Depression (PPD) she felt trapped, which explains her fantasies about wanting to disappear, to run away, to fall asleep and never wake up. Wong says she was ashamed for the way she felt and blamed herself for being weak and incapable. She viewed other mothers as more adept, maternal and with the ability to bounce back right after giving birth.

When I first held a copy of Teresa Wong’s Dear Scarlet: The Story of my Postpartum Depression, I fell in love with the cover. On it, an image of a woman’s face, the rest of her body buried deep in layers of what I first thought were hearts, but on closer inspection, are red apples. I was curious about the significance of the fruit, and would later learn, after reading the book, that Wong had a recurring dream which took place at a grocery store, where she’d climb into a bin and feel apples falling on her like rain. Wong says that with Postpartum Depression (PPD) she felt trapped, which explains her fantasies about wanting to disappear, to run away, to fall asleep and never wake up. Wong says she was ashamed for the way she felt and blamed herself for being weak and incapable. She viewed other mothers as more adept, maternal and with the ability to bounce back right after giving birth.

“Every other mom can do this. Why can’t I? I suck.” p. 50

Wong uses the epistolary form in her graphic memoir, her book a letter addressed to her daughter Scarlet. I am a big fan of the epistolary form and use it frequently in my own writing. I believe that writing letters to loved ones provides the opportunity for truth telling, allowing for an honesty and intimacy that might not happen otherwise. Wong’s images and minimal text are pleasing to the eye, making it hard for the reader to put the book down. She has a knack for taking a hard subject like mental illness, one that is often silenced, and using empathy and humour to address it directly.

Wong does not shy away from bodily functions either, which I also find refreshing. The fantasy of pregnancy and giving birth often conflicts with the reality of a long list of ailments that can come with it, including nausea, swelling, hemorrhoids, and back pain, to name just a few. I commend Wong for not ignoring these truths, and I appreciate how she uses humour to broach the changes in the body. A good example is the way she details a bout of morning sickness that involves the entire contents of her mixed berry breakfast smoothie.

After the birth of her daughter Scarlet, Wong loses over half of her blood for reasons that are unknown. She then draws a picture of her postpartum body, with an asterisk under the heading that reads, “*Not for the faint of heart*,” a refrain that she repeats throughout the book. When Wong attempts to breastfeed Scarlet, she is met with constant pain, including blisters full of blood on her nipples. She feels like a failure here too, especially after deciding not to breastfeed.

With guilt for all the ways she sees herself failing at motherhood, Wong describes feeling lost, overwhelmed, and sad. When loved ones ask how her days are going with the baby, she responds, “Boring. Yet hard.” She goes through the motions until her husband, Sunny, arrives home from work. Not being able to eat or sleep, Wong says she couldn’t remember her old life, the things she liked to do, and she felt like she was losing herself. She hated herself for feeling this way and felt like she was falling apart.

When Wong admits to Sunny that she needs help after nearly two months of what she describes as “secret shame and guilt,” things begin to shift. She is referred to a psychiatrist and a postpartum doula. She goes on medication and starts seeing a counsellor who specializes in PPD.

Along with Sunny’s support, she also has her mother, who helps with the baby, brings her Chinese postpartum food, but who is ultimately there, as Wong says, to take care of her. While Wong says she found some of the Chinese traditions annoying, like being confined to the home for a month, wearing a hat indoors, or drinking pork liver soup, she’s thankful that her mother was able to help her, and she felt supported. Wong says despite the annoyance of some of the traditions, ultimately she found them to be reassuring, a reminder “that becoming a mother was actually a big deal.”

Wong could have chosen to continue on in silence, not speaking about PPD, but she felt validated after her diagnosis and spoke about it to anyone who would listen. For Wong, this connection with others brought with it its own kind of healing: “As I shared my struggles, others began to share theirs with me, making me feel like part of a quiet sisterhood” (p. 92). When Wong begins to leave the house with Scarlet in tow, she says she starts to feel like herself again.

Toward the end of the book, Wong tells Scarlet that she didn’t write the book to make her feel guilty. She wrote it so Scarlet could understand what PPD is, and so she wouldn’t feel afraid of her own feelings. Wong says she wanted to die but is thankful that she didn’t. “I wanted to show you that you don’t always have to be strong. And that you can come back after losing yourself” (p. 105).

In her postscript, Wong introduces us to the Cantonese word, ngai, which loosely translates into the English word “endure.” But Wong says ngai goes further, acknowledging that life is full of difficulties that we all must learn to endure.

Wong not only endured, she began to experience joy after doing more therapy and learning how to be kinder to herself. After the birth of her second and third children she realized she didn’t need to make being a good mother her goal: she just needed to stay alive. That being alive, being present, was enough.

*

Claire Sicherman is the author of Imprint: A Memoir of Trauma in the Third Generation (Caitlin Press 2018), reviewed here by Mark Dwor. Her writing has appeared in publications including Entropy, The Rumpus, and the anthology Sustenance: Writers from BC and Beyond on the Subject of Food, reviewed here by Alan Belk. Claire speaks and writes about her experience as a third-generation Holocaust survivor and facilitates workshops supporting writers in bringing the stories they hold in their bodies out onto the page. Editor’s note: Claire Sicherman has reviewed books by Olga Campbell, Michelle van der Merwe and Erín Moure for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1103 A graphic memoir of endurance”

I appreciate the gripping somatic descriptions and raw emotional honesty that shine through this succinct and beautifully written review. The dream symbols, the poignant and honest diagrams, the details about maternal care and the subtleties of enduring reflect a deeply courageous heroine’s journey that is shared by many parents.

Thank you to both reviewer and author for revealing an aspect of womanhood that exposes the shame that many women and parents feel at being less than the perfect apple pie ideal. You will create hope and acceptance for many readers.

This review, and the book by Teresa Wong. offer the kind of personal and cultural education that makes Ormsby Review uniquely relevant to B.C.

Lee Reid, Nelson, B.C.