1073 Gossip, sagebrush, & injustice

Unravelling

by Josephine Boxwell

Montreal: Guernica Editions, 2020

$20.00 / 9781771835442

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy

*

As Vivian, the elder of two protagonists in Unravelling, says, “Small towns shrink to the size of fishbowls when it comes to gossip” (p. 53). Perhaps the fishbowl metaphor partly explains why, although the past several decades have seen a rise in cities as the setting of Canadian fiction, small towns still make their mark on both writers and readers. The convenient microcosm, with its defined boundaries, at once eases in the imagination and heightens intensity. Stephen Leacock, Margaret Laurence, Alice Munro, Miriam Toews, and Louise Penny — but a few Canadian masters of small town literature — provide cases in point. British-born Josephine Boxwell joins this impressive list of evokers of Canadian place. From the ubiquitous gossip, sagebrush, and dust to the cutting of the jade from the surrounding hills to the decrepit Chinese cemetery and the intricacies of salmon fishing, her time in Ashcroft is indelibly etched into Unravelling.

As Vivian, the elder of two protagonists in Unravelling, says, “Small towns shrink to the size of fishbowls when it comes to gossip” (p. 53). Perhaps the fishbowl metaphor partly explains why, although the past several decades have seen a rise in cities as the setting of Canadian fiction, small towns still make their mark on both writers and readers. The convenient microcosm, with its defined boundaries, at once eases in the imagination and heightens intensity. Stephen Leacock, Margaret Laurence, Alice Munro, Miriam Toews, and Louise Penny — but a few Canadian masters of small town literature — provide cases in point. British-born Josephine Boxwell joins this impressive list of evokers of Canadian place. From the ubiquitous gossip, sagebrush, and dust to the cutting of the jade from the surrounding hills to the decrepit Chinese cemetery and the intricacies of salmon fishing, her time in Ashcroft is indelibly etched into Unravelling.

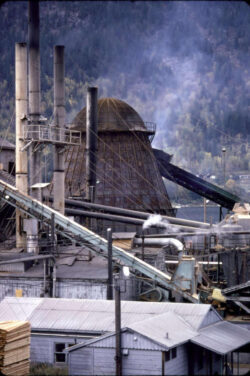

The third-person narrative consists of two intertwined threads — dual protagonists in 1994 and 2018 — connected by the fictitious town of Stapleton and, more specifically, the local sawmill. In the earlier story, Elena Reid is a ten-year old whose father disappears after the mill that employs him explodes. In the contemporary thread, Vivian Lennox, now in her eighties and fighting dementia, reckons with her role in demise of the town, the sawmill, and the Reid family. Although at disparate ends of generations, disposition, and social status, the two females share determination, independence, and conviction in the rightness of their actions. Gossip, along with injustice, leads Elena to a course of action that is ultimately self-destructive; in Vivian, largely because of her social status, the self-destruction is more gradual and internal.

Elena’s story is powerful; Boxwell impressively filters multiple traumas through the mind of an imaginative, determined child. Previous to the mill explosion, Elena lives a comfortable life — family relations and friendships are complemented by outdoor adventures. After exploring the decrepit Chinese graveyard, she impulsively camps out overnight in a barn. When she returns home the next day to find the family home vacant — and local retail outlets and streets abandoned on a Saturday morning – she believes hungry ghosts are punishing her for disobedience. However, when she finds the local school rife with military vehicles, she learns about the explosion that caused the evacuation. Elena also overhears gossip: her father disappeared after he escaped the sawmill.

The town’s initial pity for the Reid family quickly veers to scorn and shunning — a turn noticeable at a community memorial service: the remains of five men are found, but Curtis Reid is still missing. Elena and, initially, older brother Rob are determined to find their father. What they find, instead, is his abandoned truck, guarded by armed men. Elena’s detective instincts grip her, even as Rob gives up, and their mother takes a job at the local Inn, which is owned by Frank Buchanan, whom Elena has reason to be suspicious of regarding her father’s disappearance. When Audrey, her fraternal grandmother, shows up in town and is rejected by her mother, Elena, lonely and curious about family history, is manipulated into theorizing that the judgment about her father is a cover-up, a belief the girl later shares with Vivian.

The town is soon spiritually and economically gutted by the mill closure, and Curtis has become the town’s scapegoat. A rough family, the Petersons, blames Curtis for their father’s burns in the sawmill explosion and subsequent death. The police interrogate Mrs. Curtis (now jobless) threatening to take away her kids if she doesn’t tell them what they want to hear, and Vivian involves local media, spreading the rumour that Curtis was spotted near the school and demanding answers from “the main suspect in the investigation” (p. 229).

Both Frank and a second character bridge the two narratives. Mary Jones (nee Ishida), the museum curator, knowledge keeper, town conscience, and Elena’s source of local history is now her sole friend. She warns Elena, as Audrey had done, to lie low. Elena recognizes Mary’s wisdom, but is unable to stop herself. Although many indications point to his innocence – for example, a coworker provides a plausible alibi — Curtis Reid seems fated to be bearer of all blame.

Elena’s destiny is similarly sealed. Amidst a rising river, she eavesdrops on Frank, learning more to confirm he has knowledge of Curtis’s circumstances. Returning home, she discovers Rob is removing furniture, their only barricade being a pile of logs, as merchants refused to sell them sandbags. Concurrent with this emergency, police arrest her mother and a strange couple comes to the door to take Elena and Rob to separate foster homes. The siblings flee, returning only in the middle of the night to sleep. Elena awakens to find their house in flames, and her escape to the river proves an escape from this world.

In 2018, Vivian is grasping tenaciously at both her fading memory and past power. Stapleton is enduring mudslides — a consequence of the very real wildfires that wreaked havoc on the Ashcroft area in 2017 — and its commerce is reduced to the post office, Inn, and gas station. She and her husband Todd, the most senior and wealthy of the elderly town councillors, have a vision for revitalizing Stapleton. Learning of Frank Buchanan’s death, she flashes back to their uneasy alliance and her own role in the sawmill explosion. The narrative twists and turns between past and present not only mimic Vivian’s deteriorating memory; they also provide the reader with the backstory of how, in her prime, she became a hardhearted businesswoman. Despite a privileged economic upbringing, she was a victim of unbridled sexism and learned to give as good as she got.

Vancouverite Dean Masset returns to Stapleton upon learning that he has inherited the Inn and that Frank was his father. Mary and Dean become the present-day detectives, digging into the sawmill incident and uncovering Vivian’s plot. Vivian vividly recalls Mary’s opposition to the sawmill, which was constructed near a Japanese Canadian internment camp where Mary had been interred. Mary suspected – correctly — that, as the site of former secret military operations, it was contaminated. In the present, Vivian’s short-term memory is deteriorating, being replaced by the ghosts of her past, and she is institutionalized. Dean, with Mary’s help, reconstructs the ugly role Vivian played in Curtis’s disappearance, Audrey’s reappearance in the Reid family’s life, and the fire that led to Elena’s demise. While Vivian does not confess, and sticks by her current plan for Stapleton’s revival as a dumpsite for Vancouver’s waste, indications are she is getting her just desserts: being preyed upon by an equally corrupt, remote force of greater magnitude. Josephine Boxwell’s Unravelling makes gripping use of the small-town fishbowl to weave a narrative that is as much a study in societal inequities and the environmental impact of myopic capitalism as it is a mystery novel.

2020 was rich with the release of fiction set in the southern B.C. Interior. Unravelling joins Nick Tooke’s The Ballad of Samuel Hewitt, Theresa Kishkan’s The Weight of the Heart, Estella Kuchta’s Finding the Daydreamer, and David Bateman’s Dr Sad: A Month and a Day in seeing the light of day during these unprecedented times. This April, by Zoom, I will enjoy further exploring Boxwell’s fine debut with students in my Kamloops Adult Learners class – along with a classic of the region, Ethel Wilson’s 1954 Swamp Angel.

*

Ginny Ratsoy lives in Kamloops, where teaches, reads, writes, and rambles. Her latest academic publication is about a wonderful third-age learning organization, The Kamloops Adult Learners Society, (KALS) in No Straight Lines: Local Leadership and the Path from Government to Government in Small Cities, edited by Terry Kading (University of Calgary Press, 2018), reviewed by Michael Lait in The Ormsby Review. She is delighted to add that her recent retirement from academia has made it possible for her to join the board of directors of KALS, for whom she has instructed since 2007. Editor’s note: Her recent reviews include books by Caroline Adderson, Melanie Jackson, Estella Kuchta, Madeline Sonik, Mary MacDonald, Lauren Soloy, Nick Tooke, Alix Ohlin, Steven Price, and Sarah Louise Butler.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

3 comments on “1073 Gossip, sagebrush, & injustice”