1040 East Kootenay off-grid, old-style

ORMSBY REVIEW PRESS: Frederick Paget Norbury, Chapter One: The Historical Background: The East Kootenay in the late Nineteenth Century

by Brenda Callaghan

*

Editor’s note: we are pleased to present Chapter 1 of Brenda Callaghan’s hitherto unpublished biography, Frederick Paget Norbury, Remittance Man or Gentleman Immigrant? The Story of an Englishman in Canada, the introduction of which we published on January 11, 2021.

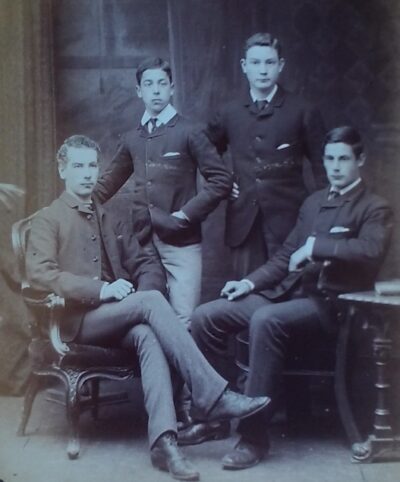

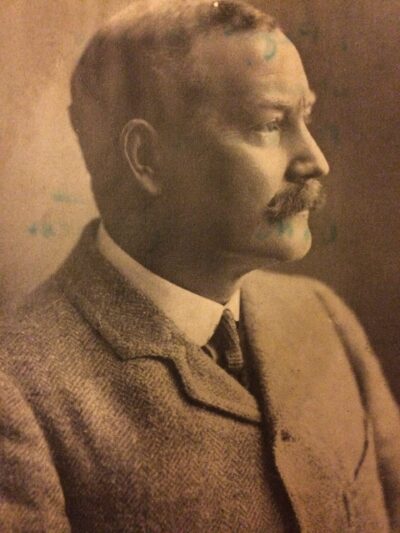

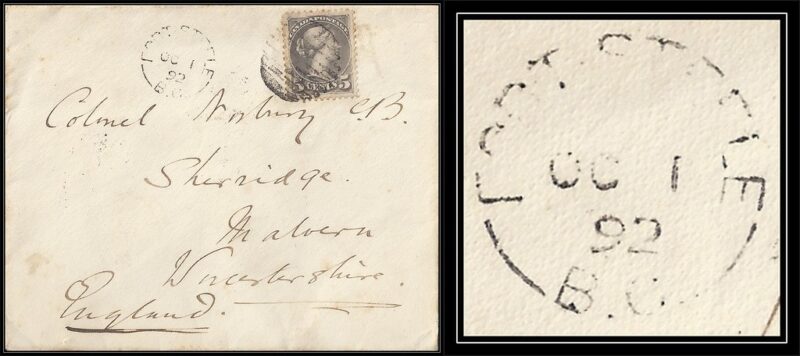

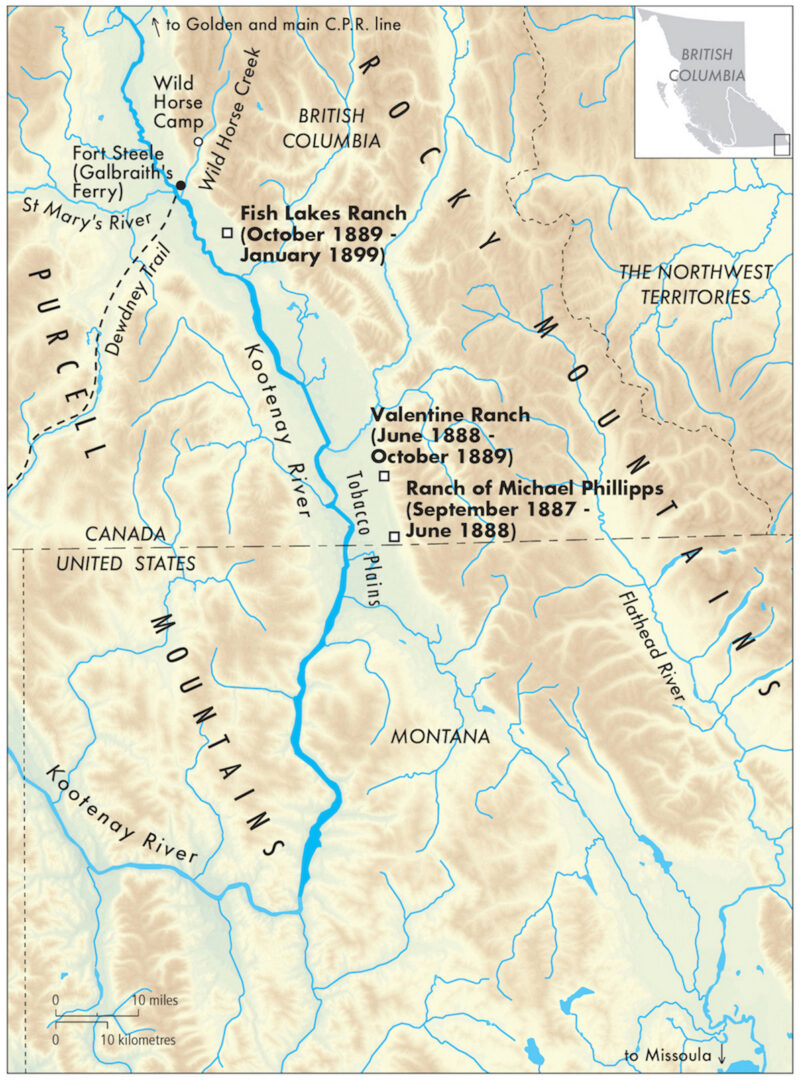

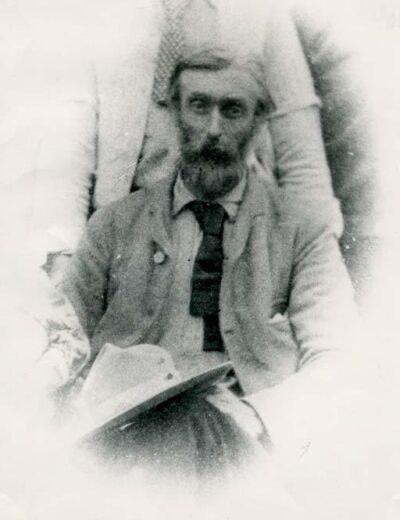

In 1887, Tommy (Frederick Paget) Norbury, who grew up on and eventually inherited an estate in England, was one of the first immigrants to travel west to British Columbia on the newly-completed Canadian Pacific Railway. Norbury (1867-1940) would stay in the East Kootenay as rancher, Justice of the Peace, Stipendiary Magistrate, and Special Constable.

In 1898, Norbury returned to Sherridge House near the village of Leigh, Worcestershire, having spent a most productive and fruitful 11 years in BC.

Sadly, Brenda Callaghan died in 2o18 before she could see the book published in The Ormsby Review Press. (Please see her biography at the foot of this chapter). Callaghan’s full 135,000-word manuscript of Frederick Paget Norbury, “Remittance Man” or Gentleman Immigrant? The Story of an Englishman in Canada, will be published in The Ormsby Review over the coming months.

We thank Brenda’s husband, Tim Gould, and her daughter, Natasha Schorb, for the opportunity to publish Frederick Paget Norbury online in The Ormsby Review Press. — Richard Mackie

*

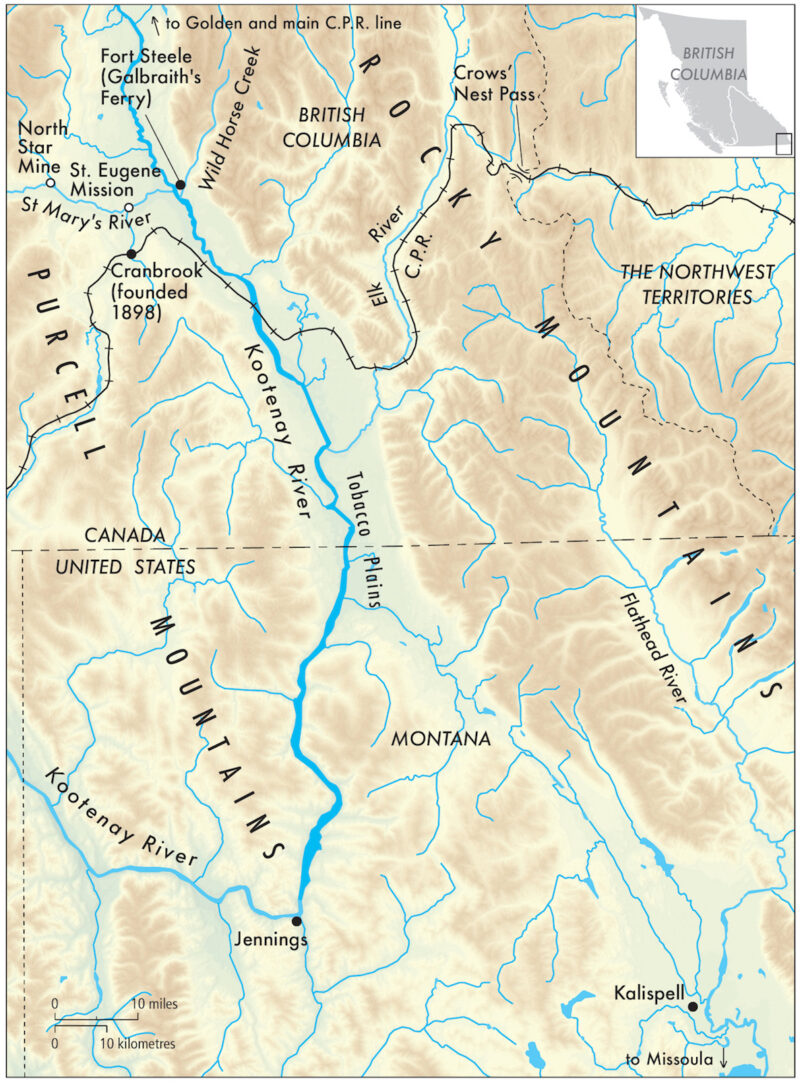

1. Early Mining and the Difficulties of Transportation

The area around what was originally known as Fish Lakes in the Upper Columbia Valley (“The Valley” as locals like to call it) where Tommy Norbury spent so much of his time years ago, gives little indication today of the tumultuous years which informed its history. On hot afternoons in August one can sit quietly by a serene pool edged by neat pastureland, below the glazed and lofty peaks of the Rocky Mountains, and the only noise one hears are the mosquitoes whining in the reeds. Likewise, Wild Horse Creek, close by to the east, epicentre of the “rush” which excited hordes of unruly miners and started the frenetic activity of the 1860s, is silent now. A few deserted ruins, a graveyard of sombre wooden crosses, and occasional holes in the earth where the bones of Chinese miners were exhumed for repatriation to China — this is all that remains. But a little to the west, Fort Steele, a re-invented “heritage town,” designed to attract and instruct visitors about the long-past mining-years, which drew so many fortune-hunters into the district, stands as testament to the economic and cultural importance of this once vibrant, now tranquil, rural area.

Although one of the province’s least accessible corners, the East Kootenay, which gives rise to the headwaters of the Columbia River, and which was the centre of the 1860s gold-rush, was fairly typical of nineteenth-century rural British Columbia. Like much of the province, it was wild, rugged, remote. Originally two separate entities comprising Vancouver Island and the mainland, the unified colony of British Columbia, which joined Canada in 1871, had only been created in 1866. This westernmost outpost of Empire, slow to join Canada, and tardy in attracting permanent settlers, was mountainous and had far less agricultural land than the other western provinces. Until 1886, when the railway finally linked the country, it could only be reached by the most adventurous — and determined. Poor transportation did not deter the men who arrived in the East Kootenay in 1864 in search of gold, however, as they had both these qualities in abundance. They were mainly Americans, and although it was a short-lived boom (within a year the easily-accessible ore had all been removed and prospectors left the area en masse) the sudden arrival of this type of transient population served to open up the area — albeit in ways that worried the Government based on the coast, 900 miles (1500 kms.) to the west. Anxiety over the influx of huge numbers of apparently lawless American miners who appeared to have made the territory their own, their casual attitude to the international border, and the distance of the gold-mines from the major population centres of the BC southern mainland, combined to cause the Government, somewhat reluctantly, to step-up its attempts to improve transportation between the more heavily-populated coast and the relatively empty areas of eastern BC bordering the United States.

Distance from the coast and the difficulties of crossing numerous north-south mountain ranges had always presented challenges to effective transportation and communication to and within this region, and was one of the main reasons why the East Kootenay, in particular, had long remained isolated and separate from the rest of British Columbia.In fact, links to the territory (and later state) of Montana were better developed than inter-provincial lines of transportation. North-south travel, that took advantage of the lie of the land, was far easier than east-west travel, and transportation improvements in East Kootenay generally took place in concert with developments south of the border.

River transport was particularly important in BC, where many communities were located in valleys and served by sternwheelers plying the waterways that linked them. The Kootenay River was of great significance here. Rising in the Canadian Rockies, it flows south into northern Montana, serving a huge catchment area to the north (as part of the Columbia River system) and helped to promote the growth of American towns such as Kalispell and Missoula, which, despite being “across the line” were often looked upon as regional service centres by Canadian miners and ranchers. Residents frequently went south into the United States for supplies of various kinds.

Concerns over the close relationship between this south-east corner of British Columbia, and the adjacent American territories to the south, prompted the Government in 1865 to commission the extension of an existing wagon road, the Dewdney Trail, from Rock Creek several hundreds of miles to the west, to the site of the gold rush at Wild Horse. One of the first travellers along this road was a judge, dispatched to maintain some sort of order in the district. Henceforth, the community of Wild Horse Creek served as the administrative centre for the region for many years. The area’s first Post Office was located there, and B. C. settlers from as far south as Tobacco Plains, a populated area many miles away which straddles the American border, had to make the arduous journey by pack-horse on primitive trails, up to Wild Horse to collect the mails.

Although it was hoped that the Dewdney Trail would eventually become one of the major roads in the area it was, at first, merely a rough, narrow track. Yet the difficulties of the terrain rendered the building of this trail an enormous task. Surveyed by the Royal Engineers, its construction was overseen by an English engineer, Edgar Dewdney (later to become Lieutenant Governor of BC, and a friend of Tommy Norbury). The Government hoped that greater ease of communication between this area and the more heavily-populated south coast, would encourage easier movement of goods and people within the colony, and would deter cross-border traffic whilst bolstering trade with coastal merchants, and improving local law and order. This did not really work, for connections with the American territories to the south remained strong. The gold rush at Wild Horse had generated a momentum of its own and American miners and prospectors would continue to infiltrate the area as later mineral discoveries were made. The border, officially agreed upon in 1846 as the 49th parallel, was largely ignored. Yet Wild Horse, as both mining town and administrative centre, had established a powerful presence, and it remained the leading community in the region until it was eventually surpassed by Galbraith’s Ferry, later Fort Steele, in 1885.

2. The Growth of Fort Steele

The community of Fort Steele, which, for a brief moment, became the principal town of the East Kootenay, and which provides the backdrop to Tommy Norbury’s story, started out life as a ferry-crossing. In the wake of the discovery of gold in 1864, 5000 people stampeded into the district to prospect for the precious metal, many of them coming from the south and west. Thus it was that an enterprising Celtic Canadian, John Galbraith, saw an opportunity to capitalise on the discovery, and in particular the difficulty of accessing the gold-fields, which lay on the eastern side of the rapidly-flowing Kootenay River. He therefore began to offer a ferry for miners, their animals and their effects. The site of the ferry-crossing would ultimately grow into a small town, known, until the arrival of the North West Mounted Police under the command of Sam Steele in 1887, as Galbraith’s Ferry. Ultimately, a bridge would be built over the river, but the ferry remained the principal method for crossing the Kootenay to Wild Horse until 1888.

For a year or so after the arrival of the NWMP, the small community of Galbraith’s Ferry served primarily as a barracks for the police detachment, and after its departure in 1888, was re-named in honour of the commander whose diplomacy had helped to ease tensions between whites and Indigenous people at a perceived moment of crisis. Immediately following the police departure, Fort Steele remained small and insignificant, but within a few years it had changed its character.20 From isolated and abandoned police outpost, Fort Steele transformed itself into a sophisticated western town. Although in 1882 there had been a mere eleven white settlers left in the area, the development of hydraulic mining and rumours about the existence of other rich mineral deposits in the East Kootenay, meant that more miners began to arrive.

Settlement of the area on a more permanent basis was also greatly facilitated by the completion of the cross-Canada Canadian Pacific Railway to Golden City, which now brought people with relative ease into the northern part of the district, many of them immigrants interested in establishing farms and ranches. In fact, the completion of the CPR In 1886 was the single most important factor in making more accessible the “far west” of Canada, and rendering it a feasible destination for intending immigrants, and even tourists, from England and Europe. Not only could immigrants now reach the far west with much greater ease, the closing of the American frontier to settlement at about the same time, ensured a good deal of interest in this area, particularly from young men looking to improve their fortunes and have fun while so doing. For as the eastern provinces became gradually more settled, the untamed nature of the far west of Canada became ever more appealing to many people drawn as much by a sense of adventure as by a need to make a living for themselves. In the years after the completion of the railway in 1886, Golden City served as an important transportation hub, as the railway brought in settlers, tourists and prospectors who all now had access to the remote East Kootenay district.

Many intending settlers ultimately found their way to the south and central part of the area, boosting the importance of Fort Steele. Indeed, Fort Steele’s potential to serve as a centre for the surrounding agricultural population, the suspected existence of yet more untapped mineral wealth in the vicinity, and anticipated improvements in river navigation on both the Columbia and the Kootenay (which served to link the community with its hinterland), held great promise for the town. In1892, discoveries of lead and silver were made in the area, and a new boom began. Fort Steele, having already surpassed Wild Horse, became a thriving business community as well as the administrative and service centre for the region. Rumours circulated that a major southern rail line would soon run through Fort Steele, and the mid-nineties witnessed the rapid growth of the town. From a small, frontier outpost, Fort Steele grew into a bustling community, which, in 1895, began to publish its own newspaper, The Prospector. The pages of this publication make it clear that at this point the town of Fort Steele saw itself as the centre of a rich mining area with limitless potential. It seemed bound for success and a long life. Indeed, between 1896 and 1898, close to 3000 people moved into Fort Steele. In August of 1896, the local newspaper could report that Fort Steele boasted two general merchandise stores, three good hotels, three bakeries, a blacksmith’s shop, two barbers, two butchers, three livery stables, two laundries, government offices, a swing-bridge, several large houses, a newspaper and the Indian Agency. By 1897 it also had a school with seventy-two pupils in attendance. A great deal of mining business was being carried on now, and that same year the Fort Steele Mining Association petitioned the legislature for a resident Gold Commissioner/Stipendiary Magistrate, and a new gaol and courthouse.

The ready availability of nearby ranch land was another important factor in the growth of Fort Steele. Land values in BC had fluctuated greatly in the decades before Norbury’s arrival in 1887, and numerous, frequent changes had been made both to the purchase price and to the conditions of sale of land in different areas of the province. The Colonial Government (which became the Provincial Government when BC joined Canada in 1871) claimed ownership of all land, which it allowed intending settlers to purchase (or pre-empt as it was called) if they fulfilled certain requirements. In the early years of colonization official policies had sometimes been unrealistic, and land expensive.

Policies were ultimately reconsidered and land in BC was eventually offered on fairly attractive terms. By 1860 it was reasonably priced, and one historian has written that in the Ashcroft area of interior, the amount usually allowed for one settler, a quarter section (160 acres), could be had for “about the same price as a good horse.” A British subject or anyone else who was willing to swear allegiance to the Queen, was permitted to take a rectangular parcel of unsurveyed land on condition that he lived on it and improved it and registered his claim with the district magistrate. A settler was also entitled to take adjoining unclaimed land for the same price per acre as his original claim. Land policies in the east of the province were particularly generous. The Land Ordinance of 1861 decreed that east of the Cascades the size of a piece of land which could be pre-empted be increased from 160 to 320 acres, doubling the size of the available parcel to each applicant. Consequently, land was quickly taken up and large ranches established. By the time of Norbury’s arrival, under the terms of the Land Act of 1884, adjacent land up to 160 acres could also be added to the original 320-acre parcel for no extra cost.

Most settlers who pre-empted land in this area, did so with the intention of raising cattle. As in much of the interior of the province, this proved to be the best use of agricultural land. Despite the misguided and often misleading claims made by some land speculators trying to lure wealthy English people seeking a “gentlemanly” means of livelihood, that fruit-growing was the most promising agricultural pursuit in British Columbia, there was very little land in BC suitable for arable farming of any kind. Cattle-raising, on the other hand, was suited to soil, vegetation and climate, and the demand created first by the fur trade, then the gold rush and railroad construction camps, and later by the logging camps as well as growing settlements, meant that cattle ranching was fairly lucrative. Indeed, ranching dominated the economy of the interior of BC in the twenty years prior to 1885, and by 1870 the province became self-sufficient in beef production, with animal products the chief agricultural export between 1872 and 1900.

Fort Steele, then, came to prominence amid a wave of settlement contingent upon the promise of profitable mining and the availability of agricultural land. From an isolated ferry crossing, it evolved into a police barracks and ultimately a busy community serving a broad catchment-area. It fulfilled the needs of miners and agriculturalists alike, providing a wide range of services to local inhabitants. The opening of the productive North Star Mine in 1892, underscored the importance of Fort Steele as a shipping point (see below) for the lead and silver mined there, in addition to the ore from the Sullivan and Eugene mines close by, and convinced residents of the strategic importance and future prosperity of their town.

3. Improvements in River Transportation

The heyday of Fort Steele coincided with the high point of river transport. The coming of the sternwheelers on the Kootenay River was responsible, in part, for the rise of the mining industry and the growth of the town. In the light of poor road transportation, it is hardly surprising that the area, like so many other remote parts of Canada’a interior, should be opened up initially by paddle wheelers. The rivers were the natural highways of this largely inaccessible country. The main difficulty with river transport, of course, was that the season could be quite short, and was entirely dependent upon the vagaries of the weather. An exceptionally cold winter and a late spring melt, could cause the ice to linger long into April, or even May, effectively blocking the rivers until warmer temperatures facilitated successful navigation. Much the same could be said about overland transport, however, which, by the same token, could be severely affected by excessive snowfall in winter, or deep mud in periods of heavy rainfall.

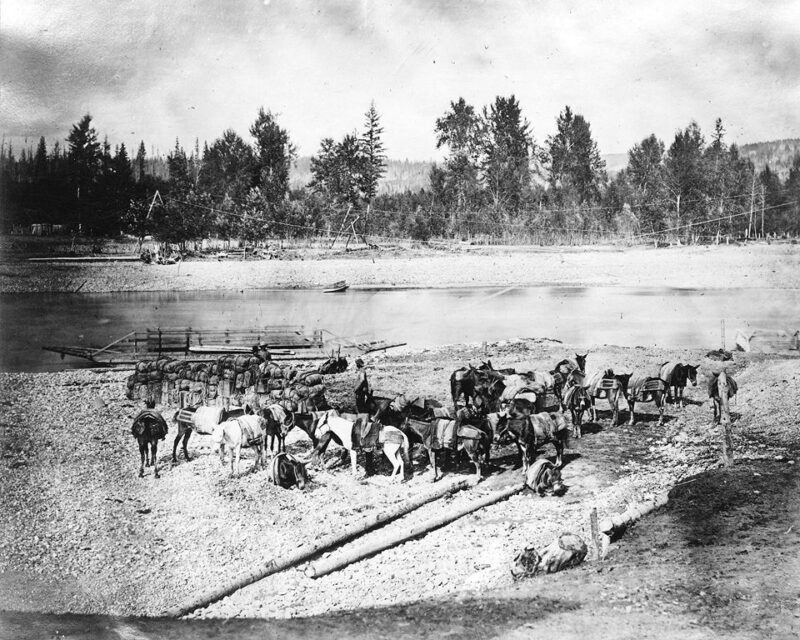

As previously mentioned, settlers had often arrived in the area from the north, arriving on the CPR main line from the east of Canada which deposited them at Golden City. From here, passengers would take the riverboat that plied between Golden City and Windermere, a lakeside community near the limit of commercially navigable water on the Columbia River system. This enterprise was begun by a local entrepreneur by the name of Armstrong. Frank Armstrong was one of the first white settlers in the East Kootenay. Originally from Quebec, he arrived in the area in 1881 as an employee of the CPR, and was involved in the exploration of the Rocky Mountains in the Kicking Horse Pass area, where a feasible route for the railway track was being sought. He left the employ of the railway in order to pre-empt 320 acres of land on the east side of Columbia Lake, where he later established a home and a farm, and grew potatoes from seed which he brought in from Montana by pack-train. An enterprising fellow, he constructed two flat-bottomed boats that he used to carry his crop across the lake and then down the Columbia River to Golden, where he sold his potatoes.

The journey he undertook by boat from his home on Columbia Lake to Golden City, convinced Armstrong that reliable river transportation was an essential service for settlers resident in the area. He thus made a decision to construct and operate a riverboat on the stretch of water between the community of Windermere on the Lake of the same name, and Golden, on the Columbia River. Thus began the long and successful career of Frank Armstong, ferry-builder and operator.

Armstrong’s decision did much not only to cement Golden City’s importance as a transportation centre, but also to stimulate population growth in the East Kootenay generally. But the ferry-link to and from the railroad at Golden City was far less convenient for those who were based — or wanted to be — in Fort Steele and the mines and communities of the south, than it was for settlers in the north. As mining became more important throughout the 1890s, and increasing numbers of settlers headed for the central and southern part of the region, it became clear that entering the area from the north just would not do. At Windermere, after leaving the sternwheeler, any travellers bound for Fort Steele, Wild Horse or Tobacco Plains, were forced to push on using a pack-route over very rough terrain. One might take the stagecoach, use one’s own horses, or even proceed on foot.

Arriving in the area in 1887, two English adventurers, J.A. Lees and W. J. Clutterbuck complained loud and long about their tortuous attempts to push south down the valley:

Stories of the difficulties of packing and the ludicrous mishaps caused by incompetency meet one at every turn in a country where practically all traffic is carried on by this means, for between Galbraith’s Ferry and the South, West and East, for 150 miles in every direction, there is nothing in the shape of a road, but only the narrow track on which one horse at a time can thread his way through the interminable forest.

This was clearly a difficult journey, and even after the opening of the wagon road which, after 1892, allowed travellers to traverse the length of the valley as far as Fort Steele by stage coach, water transport held the promise of a smoother, much more pleasant journey. What was needed was a southern water route giving access to the region, one comparable to that serving the north.

Thus it was that private enterprise, American as well as Canadian, stepped in to try to ameliorate the situation — and not simply for the benefit of passengers. During the 1890s the area was beginning to prosper, and the hauling of freight of various types held great pecuniary promise. The opening of the North Star Mine above Fort Steele in 1892, prompted the demand for an efficient means of moving the silver ore out of the area. Two American businessmen, Walter Jones and Harry DePew, were first to come up with a plan to establish a transportation route by means of the Kootenay River (much faster-flowing yet more hazardous than the Columbia) south from Fort Steele and “over the line” to the river-side railway town of Jennings, Montana. From here the ore could be efficiently dispatched by rail for processing at American smelters. The Americans formed a company, The Upper Kootenay Navigation Company, which built and put into service the first sternwheeler on the Kootenay, the Annerley. It made its maiden voyage in 1893, travelling upstream from Jennings to within fifteen miles of Fort Steele. This event was considered by locals to be very significant, as the cost of supplies of every type immediately plummeted. After this success, Annerley provided a regular service on the Kootenay, taking two and a half days to go from Jennings to Fort Steele, and eight hours to return.

Soon afterwards, a rival Canadian company was established: The Upper Columbia Navigation and Tramway Company, and this company built the second steamboat, Gwendoline. Frank Armstrong was instrumental in forming this company, and in fact he operated a great many different sternwheelers throughout his successful career. Although he had virtually no competition on the quieter Columbia, the Kootenay was a different proposition. In the years after Gwendoline was launched, several more boats were built and put into service on the Kootenay, new companies were formed, and a lucrative trade in hauling freight was established. Business was brisk during the mid-nineties’ mining boom, and initially railway-construction created a great demand for river-transported goods of all types.

River-transport was not without its risks. In fact, the Kootenay River presented some significant problems as far as navigation was concerned, chief among them the treacherous Jennings Canyon, which claimed several of the riverboats over the years, and sometimes involved hair-raising rescues. This is not to imply that accidents never happened on the more sedate Columbia. Armstrong’s first boat, Duchess, came to grief near Golden City in 1887, whereupon he constructed a second Duchess to succeed her. He would eventually build and operate over a dozen other boats on this river, carrying both passengers and freight.

The riverboat era was short-lived, however; and it is ironic that the development which stimulated a huge increase in river traffic — the construction of the railway in the southern part of the district — was ultimately a major factor leading to the decline of the business which had made it possible. The completion of the CPR line through the Crows’ Nest Pass in 1898, meant that now freight and passengers alike could be transported much more efficiently into and out of the southern part of the Columbia/Kootenay Valley river system. The railway was not as bound by the whims of weather, nor did it imperil its passengers and crew by attempting to negotiate dangerous natural hazards. And as far as the Canadian Government was concerned, it operated entirely within Canadian borders, and was thus completely under Canadian control. For all these reasons, it was altogether a much more satisfactory way of moving people and goods. The riverboats on the Kootenay were sold off, railway trains taking over their passengers and freight. Thus, a scant year from its heyday in 1897, came the end the age of the sternwheeler on the Kootenay.

Armstrong was able to prolong his operations for a slightly longer period on the northern river. Despite improved overland travel, his riverboat service between Golden City and Windermere remained the chief transportation route in the north of the area for a few more years. As immigrants poured into the northern part of the valley at the turn of the twentieth century, ore still needed to be freighted out. Armstrong continued to service this need, making his final river trip between Windermere and Golden City in 1914, just before river transport finally gave way to the railway train, which by this time had penetrated the whole length of the Upper Columbia.

4. The Decline of Fort Steele

The coming of the railway not only caused the demise of the riverboats, it was also instrumental in the death of Fort Steele. Despite all the predictions on the part of the local newspaper, and the hopes of its citizens, Fort Steele did not retain its position as the principal East Kootenay community in the long term. By the last years of the nineteenth century it had become clear that the neighbouring settlement of Cranbrook, and not Fort Steele, would become the divisional railway headquarters for the new Crows’ Nest Railway, now snaking its way west from the Rocky Mountains. The town would thus be by-passed, and the new railway would henceforth convey the ore previously transported south by river. When the CPR decision was announced, businesses and offices of all types lost no time in relocating to the new town of Cranbrook, which now became the chief service centre of the district. By 1904, Fort Steele, once the promise of the East Kootenay, had fallen into decline.

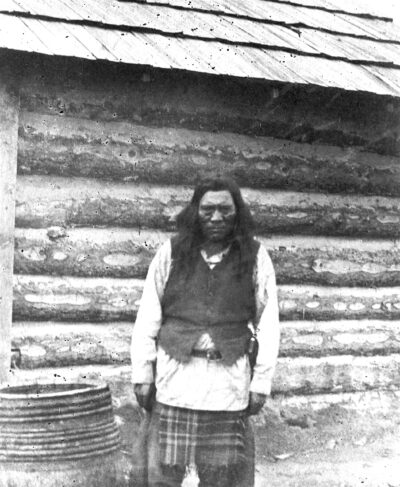

5. Indigenous Peoples and Immigrants

Settlers from Europe who attempted to make a new home for themselves here, typical of immigrants to North America more generally, had not encountered Indigenous peoples before, and many were frightened by what they considered the latter’s strange appearance and odd behaviour. Influenced by “scientific” theories of the superiority of the white races and the morally deficient “savages’” of North America (commonly-held attitudes in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century, of which we will hear more later). European immigrants, far from all that was familiar and understandable, felt insecure and vulnerable and were very fearful for their safety. For their part, many Indigenous people felt resentment over loss of their traditional hunting grounds because of the increasing intrusion of ranches and farms. The interracial violence in the western United States was too close for comfort. The spectre of the “Indian Wars” of the American Pacific Northwest was ever-present. Relations were thus strained between whites and Indigenous people throughout the province, and in North America more generally.

The policies of the government were ultimately decisive in determining the nature of white/Indigenous relations. In the very early years of BC’s development, thanks to a fairly sympathetic, cautious and conciliatory attitude on the part of the BC Government, the colony (and later province) managed to avoid the bloodshed so common south of the border. Under the governance of James Douglas, who took seriously the concerns of Indigenous people and tried to be fair in his land policies, the early years of development were marked by peaceful co-existence. Unfortunately, the successors of Douglas did not share his qualities or views, and the pressure brought to bear by the arrival of increasing numbers of European settlers served to exacerbate Indigenous-white relations.

Historically, the early fur-traders who had pre-dated the settlers, had sought to accommodate themselves to the Indigenous peoples whom they needed as allies and trading partners. Thus there had been a degree of compromise and “rubbing along” of sorts. Settlers, however, had no need to get along with the Indigenous people. Indeed, they saw them as an impediment to progress, a threat to their intended plans to develop the land and to re-create a “civilised” landscape out of “waste”. European attitudes toward the land and ways of relating to it were at odds with Indigenous ways. Whereas Indigenous people had been used to hunting and gathering on the land for centuries, and, in much of the interior and eastern part of the province, had moved over vast areas in nomadic groups, leaving little permanent imprint on the land, Europeans looked upon the land as a resource to be permanently settled and exploited. To European eyes hunting and gathering were inferior to cultivation, and the Indigenous people had no legal right to claim land they did not cultivate and permanently settle.

This attitude was reflected in the land policies of the Government after Douglas, which regarded the land of BC as unoccupied if uncultivated and unimproved, and made such land available to settlers, in so doing showing a blatant disregard for the claims of Indigenous peoples who may have been using such lands for hunting for centuries. Unlike other Canadian provinces, BC signed few land treaties with Indigenous peoples, and this neglect to address issues of tremendous magnitude has spawned a thorny legacy, which into the present time continues to present huge problems, leading to great animosity on both sides.

Another source of friction between white and Indigenous people was the method the whites chose to police the province. When British Columbia became a part of Canada in 1871, the federal government divided up the province into “Agencies” and appointed “Indian Agents” to oversee them. The latter had sweeping powers. They acted as Justices of the Peace and had the power to appoint Indigenous chiefs and to remove any they did not like. Some Agents were successful and well-liked, but the heavy-handedness of others, and their lack of understanding of Indigenous culture, was the cause of much ill-feeling. Likewise, the deliberate disregard of, and lack of respect for traditional ways, and misunderstanding of Indigenous values on the part of whites generally, often led to a build-up of tensions. An incident which led to the summoning of a detachment of the NWMP who based themselves at Galbraith’s Ferry for a prolonged period, has already been mentioned, but is worth recounting in some detail.

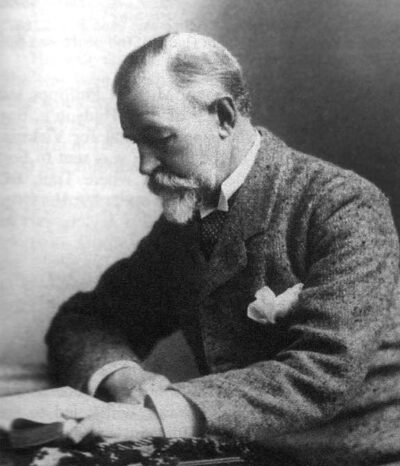

The name of Colonel James Baker has been closely linked to the development of the East Kootenay area. The son of a wealthy English family, he founded the town of Cranbrook, which succeeded Fort Steele as the largest and most prosperous town of the East Kootenay, and which he named for his home in Kent, England. He and his son, Hyde, became good friends with Tommy Norbury during his time in the province, and had a huge influence upon his life in BC Like so many other gentlemen immigrants, Baker had travelled widely before arriving in Canada. He settled in the Kootenay area in 1884, and in 1886 became politically active, serving as a Member of the Legislative Assembly as Provincial Secretary, Minister for Education and Immigration and Minister for Mines. He was also a successful businessman and rancher. He formed a company to develop the coal mines in the Fernie area, and to ship the coal out by rail, and he bought land from the Galbraith family which he initially used for ranching, but later developed as the townsite for Cranbrook.

The land he purchased with a view to ranching and which he later sold in the form of town lots, became the focus of much controversy. The area known as Joseph’s Prairie was an attractive, open piece of ground that had traditionally been used by the Kootenay Indians for hunting and camping, before being sold to the Galbraiths, on condition that it should not be fenced. For as long as the land was held by the Galbraiths, this promise was honoured, but when Baker later bought this same land, he disregarded the Indigenous desire to continue using it, and Galbraith had no way of enforcing the previous agreement. This angered Chief Isadore, a well-respected and influential Kootenay chief, and Baker felt compelled to call upon the services of a contingent of North West Mounted Police, based in Lethbridge and under the command of Sam Steele, to help diffuse escalating tensions. The situation grew more complex and potentially dangerous when an Indigenous person, charged with the murder of two whites, was imprisoned by white authorities, but then released, unlawfully, by Isadore. Fortunately, Steele was cut from different cloth than Baker. He was far more sympathetic to Indigenous points of view, and he and Isadore had a great deal of mutual respect. The dispute was resolved peaceably, tensions de-escalated, and the police presence in the area was short-lived.

Baker, however, succeeded in hanging on to the land he claimed as his own. Indeed, he appears to have been determined that Joseph’s Prairie should make him a wealthy man. In the late 1890s, it was rumoured that Colonel Baker stood to gain personally by the decision of the CPR to run the long-awaited railway-line through Cranbrook, formerly Joseph’s Prairie, to the detriment of Fort Steele. It was popularly believed that Baker had used his political influence to determine the route the railway would take, and stood to profit handsomely from the division of his land into town lots when the construction of the railway divisional centre began there. Whatever the factors influencing the CPR’s decision, there can by no doubt that the route selected had the effect of creating the new town of Cranbrook, thus enriching Baker and his family, at the expense of Fort Steele. Baker and his son eventually returned to live in England.

Baker’s attitude to Indigenous peoples and their concerns was fairly typical of those of immigrants, often English, who found their way to western Canada, and attempted to impose their own values on a culture and environment completely at odds with that of their homeland. Often motivated by a desire to “civilise” the wilderness and to introduce more “advanced” European ideas into areas they considered “backward,” while at the same time enriching themselves by involvement in various developmental schemes, men such as Baker played a huge role in the settlement of Canada.

It was by no means the case, however, that Colonel Baker’s involvement in this area’s growth and development was always and only informed by self-interest, although it should be noted that he does appear to have been much more concerned with the welfare of the white newcomers, than with the original inhabitants. As the area’s political representative, he worked hard to bring certain improvements to the Kootenay area, which, without a doubt, had important advantages for his white constituents. He drew public attention to the mining potential of the area, for example, and he also wanted to see greater opportunities for basic education for children. Concerned about the parlous state of the roads, he helped also to facilitate the development of transportation links generally.

6. Kootenay Englishmen and other gentlemen

Aside from Baker, many other high-profile English immigrants made their mark on this region. Two others are particularly deserving of mention because, as we shall see, not only did they play a role in the Norbury story, but they represent the two poles of English attitudes towards Indigenous peoples — on the one hand, the high-handed disregard for Indigenous interests typical of the “Baker” mentality, and on the other, a more sensitive accommodation to and appreciation for Indigenous ways which helped to ease racial tensions. Norbury would become very aware of both attitudes.

Into the first category falls a wealthy “gentleman immigrant” and avid sportsman, William Adolph Baillie-Grohman, who was of aristocratic lineage and of mixed Anglo-Irish and Austrian ancestry. He was also a friend of Henry Barneby, a travel-writer and personal friend of the Norbury family, of whom we will hear more. Baillie-Grohman was a prolific writer himself, and had travelled widely. Under the pen-name “Stalker,” he had documented many accounts of his numerous escapades in the great outdoors of western Canada and the United States. At the time of Tommy Norbury’s arrival in the Valley, Grohman was already a resident, living about twenty miles south of Windermere, where the two major river systems of the area, the Kootenay and the Columbia, come to within a few hundred yards of each other.

There was a good reason for his choice of location. Always on the lookout to make money and a name for himself, he came up with a scheme to divert water from the Kootenay into the Columbia river system, by means of a specially-constructed canal, where the two rivers came to within striking distance of one another. In Grohman’s view, the consequent reduction in the volume of water in the Kootenay River which this linkage of drainage areas would involve, would help to alleviate problems of flooding much further downstream at a place now named Creston, where Grohman hoped to establish an agricultural community. He thus formed a limited company, the Kootenay Syndicate, and set about raising money in England (where he was well-known) to finance his ambitious scheme. As we have previously heard, this was an era when Canadian land developers commonly came up with schemes to enrich themselves by attracting potential immigrants to areas where, allegedly, they could purchase good land cheaply, settle and make a living from promising agricultural pursuits.

Grohman’s plans were far-reaching, complex, and by no means guaranteed to work. The diversion of river-water was only one aspect of a complicated project that also required the attempted lowering of water levels in Kootenay Lake in the West Kootenay by excavation and strategic dredging. There were many delays and bureaucratic problems, as well as numerous objections raised by parties who felt threatened by any proposed changes to natural river-flow and lake levels. For example, concerned about the potential of the Columbia River to flood if extra water were diverted into it, the CPR anticipated a grave threat to its current operation at Golden, and raised loud objections, as did other owners of property bordering the Columbia River and Lakes. Indigenous peoples were also concerned about the potential for damage to their gardens along the edge of the Kootenay.

In order to have his project approved by the Government, Grohman was instructed to build a lock on his canal that would control water levels on the Columbia, and facilitate navigation. Grohman’s scheme dragged on for many years, and was not an overall success, although he did manage to construct his canal. In 1887, after many unforeseen problems, he established a sawmill at the site of his proposed canal that he used to prepare the timber for his project. The canal, when completed in 1889, did improve transportation in the Columbia Valley temporarily, as riverboats briefly provided a continuous transportation service between Golden and Fort Steele, transferring goods and passengers from the Columbia to the Kootenay Rivers. As a result of the construction of the canal, Grohman laid claim to large expanses of land on the Kootenay River and around the Creston area. Ultimately, however, the project did not change water levels sufficiently to prevent flooding at Creston, nor was the canal a long-term success, as sternwheelers experienced problems trying to navigate the lock on the canal. Ultimately Grohman pulled out of the scheme, and flood-control in the “Kootenay Bottom-lands” was subsequently undertaken by another company. Grohman’s dreams of making his fortune by creating an English enclave of immigrant farmers had proved unworkable.

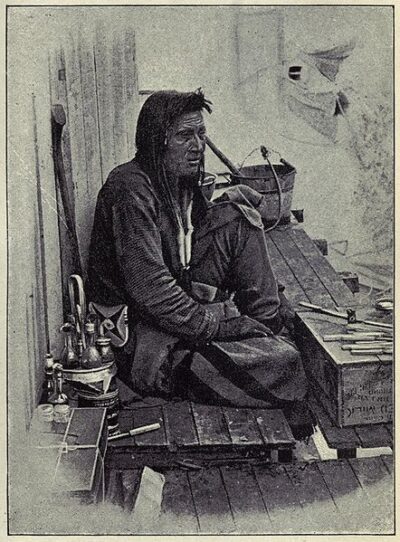

A completely different kind of immigrant, a far cry from either the hard-nosed Baker or Baillie-Grohman, but a person who played an extremely influential role in the Norbury story, was an Englishman by the name of Michael Phillipps. Michael Phillipps was an early resident of the East Kootenay and acted as Norbury’s host, mentor and companion when the young Englishman first arrived in the country. Over Tommy’s eleven or so years in the area the two established a firm friendship. Something of an enigma, Michael Phillipps left few records of his life in Canada, although he had a large family and many of his descendants live in the area today. Historians know little about this man’s life, although he undoubtedly played a leading role in the nascent East Kootenay pioneer society.

The son of a clergyman who had spent much of his time in Wales, Phillipps was born in Hereford, England, in 1840. He emigrated to Canada when he was twenty-four years old. Phillipps had lived in the East Kootenays for over twenty years prior to Norbury’s arrival, first working as a clerk at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s post established in Tobacco Plains (later relocated to Wild Horse), and then as a rancher working land in the vicinity of Tobacco Plains, south of Wild Horse. In fact, he was the first homesteader to take up land in the Kootenay district, and this he did in 1867. He built the first Customs House at Cranbrook, and worked as the first Customs official in the area. Concerned about the amount of cross-border trade, the government entrusted Phillipps with the task of overseeing the Customs service.

As an educated, highly literate man, Phillipps held, over the years, a variety of local government positions, and was well-known and respected in the area. An outdoorsman of formidable endurance and resourcefulness, he was the first white man to negotiate the Crows’ Nest Pass, and to draw attention to the coal deposits there. He was a man of diverse accomplishments. Like Tommy Norbury, he had “bookish” interests and a flair for writing, penning several well-crafted newspaper articles and keeping detailed meteorological journals. But he was also a very practical man, among other things, erecting a sawmill and building a riverboat. One of his major accomplishments was an engineering feat — the construction of a bridge over the dangerous Elk River.

An unconventional character, Phillipps lived the life of a somewhat reclusive “man of the soil,” having thrown off any social pretensions he might have inherited during his middle-class English upbringing. Indeed, his chosen way of life indicated that he had rejected the values and standards of English middle-class life. Phillipps maintained little contact with his family in England, and the only relative to take an interest in his life in Canada was his sister, Augusta Grasset, who endlessly pestered Tommy about the details of her brother’s marriage. Mrs. Grasset was particularly interested to know about Phillipps’ wife. His sister was extremely status-conscious, a fairly typical affliction in nineteenth-century England, and she seems to have been more concerned to know if Phillipps’ wife was “respectable” enough (i.e. from a suitably socially elevated family) to be brought back to visit England, than she was about her brother’s overall welfare.

Michael Phillipps kept the details of his marriage secret from his sister and other English family members, and not without good reason. In a world where social rank and family connections were everything, where marriage was regarded more as a business-arrangement than a romantic coupling — a means of cementing family alliances and safeguarding property and reputation — Phillipps’ choice of bride would have been regarded as a social disgrace. Phillipps did the unthinkable as far as English upper-class decorum was concerned. He married an Indigenous woman (albeit of the “royal family,” as Tommy phrased it in one of his letters home, for she was Rowena, daughter of Chief David of Tobacco Plains).

The marriage appears to have been successful. With her he raised a large mixed-race family, and adopted a lifestyle that incorporated many aspects of his Indigenous wife’s culture. His skills, knowledge and wisdom were much appreciated by the young Tommy Norbury, and they had an enormous impact on him during his years spent living in the region. Over the years Tommy regularly helped Phillipps on his ranch, and he obviously felt a fondness for and an obligation toward the man in whose household he resided for the first difficult months in the country. Phillipps had his faults, however; and, like many English settlers of the time, he was certainly not averse to dabbling in land speculation. He was involved, for example, in a scheme designed to lure English immigrants to the area with a view to growing apples commercially, a scam that, like so many others, proved unsuccessful. Yet his other qualities made him an effective counterweight to Baker, with whom Tommy also became very friendly, and he helped increase the latter’s sensitivity to Indigenous concerns. So influential was Michael Phillipps in the life of Tommy Norbury, that without him, one wonders if Tommy Norbury would have had much success at all.

The above brief overview of the history of this isolated, yet economically and culturally complex, part of British Columbia sets the stage for the tale of a particular young man who came to live here in 1887. While Tommy Norbury did not stay long, during his twelve-year adventure he did leave his mark. The ranch where he spent most of his time — and which has passed through many hands since it was first established — was popularly known as Fish Lakes, an idyllic place of great natural beauty, now designated a park named Norbury Lake in his honour.

*

Brenda Callaghan, 1951-2018. Brenda Callaghan was born in Barrow-in-Furness, a small industrial town in the English county of Cumbia, in 1951. In defiance of local convention, Brenda remained in high school to earn A-levels and subsequently entered teacher training college, at what is now Leeds Beckett University, in 1969. Brenda’s teaching skills allowed her to immigrate to Canada in 1975 and eventually to fill teaching posts in Prince Rupert and Kitimat. Shortly after her daughter Natasha’s birth, Brenda’s first husband fell ill and left Brenda widowed in 1981. Brenda returned to academic studies in 1984 and over the following years was awarded a BA (Hons), an MA, and a PhD from the University of Victoria’s Department of History. Strongly affected by the loss of Natasha’s father, Brenda’s graduate and post-graduate research explored the cultural significance of customs associated with birth, death, and marriage in England’s post-industrial north. It was while conducting this research that Brenda met her second husband, Tim Gould, in Cumbria in 1991. During and following the completion of her PhD in 2000, Brenda worked as a sessional instructor at UVic and England’s Open University. In Cumbria, Brenda’s research was of broad public appeal and in the 1990s she established a reputation as an engaging guest speaker at local history societies. After settling with Tim in the East Kootenay region of BC in 2002, Brenda followed her interest in local history to the nearby Fort Steele Museum and Archives. It was there that Brenda, with the help of the curatorial staff, unearthed the letters of Frederick Paget Norbury. Brenda was no stuffy academic. Widely travelled, she saw much of Europe, North America, and the South Pacific. She ran a successful Bed & Breakfast in the Canadian Rockies, enjoyed live music and the theatre, was a scuba diver, keen hiker, and skier, and to the surprise of many, an enthusiastic long distance wilderness paddler.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1040 East Kootenay off-grid, old-style”

Michael Phillipps is my great Grandfather! So cool to see his story in books!!