1030 Blacks in BC then and now

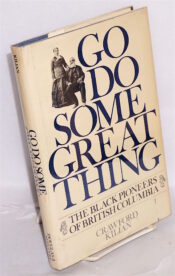

Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia

by Crawford Kilian, with a foreword by Adam Rudder

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2020 (3rd edition, first published 1978)

$26.95 / 9781550179484

*

“Where Are You From?” Growing Up African-Canadian in Vancouver

by Gillian Laura Creese

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019

$34.95 / 9781487524562

Both books reviewed by Jean Barman

*

Blacks in British Columbia then and now

Blacks in British Columbia then and now

Blacks, as the term is used by Crawford Killian in Do Some Great Thing, describe persons of visibly darker skin tones than those perceiving themselves as “white,” for which reason they have sometimes had, although not necessarily so, historically different life experiences in British Columbia than have their paler skinned counterparts. Blacks were among the earliest nineteenth-century arrivals, as explained by Kilian, and are part of British Columbia into the present day, as evoked by Gillian Creese in “Where Are You From?” Whether read together or separately, these two accessible and well written books give us pause as to how we treat those in our midst who we might perceive as different from ourselves and what we can learn on taking their experiences seriously.

Blacks were among the earliest non-Indigenous arrivals in British Columbia. It is over a century and a half ago, April 25, 1858, that as the gold rush that would bring today’s British Columbia into being was more rumoured than acted upon, an American steamship arrived at the then British colony on Vancouver Island “direct from San Francisco with 450 passengers on board, the chief part of whom were gold miners who have since left in boats and canoes for Frasers River.”

While note was taken at the time of the large numbers of American, British, and other white men on board who had come to mine gold, it is indicative of the past’s many understories that no one seemingly mentioned the 65 free Blacks also on board, one of whom had negotiated in advance with Vancouver Island’s governor James Douglas for their equitable treatment should they leave California. While we cannot know with certainty, we can speculate on the extent, if any, Douglas having a part Black mother played in his decision.

Slavery had been abolished in the British colonies in 1834, whereas the United States was characterized by a mixture of slave and free states and territories prior to slavery’s abolition in 1865 consequent on the American Civil War. The Vancouver Island arrivals had every reason to fear for their future, given the United States Supreme Court had a year earlier denied citizenship both to enslaved Blacks and to their descendants.

The April 1858 arrivals, whose stories Killian recreates almost as if they are living in the present day, would be the nucleus of several hundred free Blacks, many with families, who early on crossed the American border to make their homes very reputably in Victoria and on the nearby Gulf islands, including Salt Spring.

Blacks repeatedly took the initiative in ways that benefitted settlers generally. At a time when residents feared Vancouver Island’s takeover by nearby Americans, which was a real possibility, Blacks formed for defensive purposes the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps with its own uniforms and drill hall. All the same encountering racism fed by Victoria’s considerable American population, Blacks persevered both in Victoria and on some of them moving to Salt Spring Island on its becoming possible to take up land there.

Blacks would continue to arrive into the present day, among them Vancouver’s favourite life guard, Joe Fortes from Barbados who Killian aptly terms “the guardian of Vancouver’s children.” On a personal note, I still recall the very elegant elderly white woman who came up to me at the end of a talk I gave some years ago to share with me her pride in having been as a child “taught to swim by Joe.”

*

Moving from then to now, Gillian Creese puts perspective on a generation of offspring of more recent Black immigrants to Vancouver. Following up on her earlier The New African Diaspora in Vancouver: Migration, Exclusion and Belonging (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), which through interviews with arrivals from sub-Saharan Africa evoked the growth of a community identity, “Where Are You From? turns to that generation’s children. It probes the life experiences of their Growing Up African-Canadian in Vancouver, to quote the book’s subtitle.

Moving from then to now, Gillian Creese puts perspective on a generation of offspring of more recent Black immigrants to Vancouver. Following up on her earlier The New African Diaspora in Vancouver: Migration, Exclusion and Belonging (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), which through interviews with arrivals from sub-Saharan Africa evoked the growth of a community identity, “Where Are You From? turns to that generation’s children. It probes the life experiences of their Growing Up African-Canadian in Vancouver, to quote the book’s subtitle.

I found the second-generation’s stories fascinating. Due to family support, all the research participants graduated from high school and pursued some form of post-secondary education. As indicated by the book’s title, offspring felt they were living “under a microscope” owing to “popular discourses about Black masculinity and femininity.” Males tended to be popular by virtue of being able to play in adolescence “the ‘cool Black guy’ from hip hop and celebrity sports culture,” whereas “girls remained on the fringes…because of the lack of Black female role models in popular culture whom they can emulate.” Nonetheless, Creese concluded, “the sense of optimism and resilience among research participants should not be overlooked.”

These two engaging books reminded me time and again of the Black students from the Maldives, Kenya, and Jamaica who I supervised to the completion of their doctoral dissertations during my years at the University of British Columbia, each of whom similarly made me aware through our many conversations of the big and small differences that skin tones can make to individuals’ lives. On doing so I reflected once again on the powerful words with broader meaning that one of them, Yvonne Brown, included in her dissertation published as the very readable Dead Woman Pickney: A Memoir of Childhood in Jamaica (Waterloo Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2010) as to how:

All the components of globalization have had their antecedents in land appropriations and the extermination of indigenous peoples, the slave trade in African bodies, mercantilism, colonization, and empire building. In the contemporary discourses on globalization, Africa is assigned an inferior status or else excluded entirely…. Things have not changed for Africa in the so called “new world order.”… The brutal consequences of imperialist world domination are with us today, celebrated by the descendants of the founding fathers of empire but cursed by the descendants of the enslaved and colonized.

There is much to ponder.

*

Jean Barman’s books, co-edited volumes, articles, and book chapters on British Columbian, Canadian, and Indigenous history have won fifteen Canadian and American awards, most recently the Governor General’s Gold Medal for Scholarly Research. She is professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia, a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, recipient of the George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2016 was the proud recipient of an Honorary Doctor of Letters from Vancouver Island University. Editor’s note: Jean Barman’s four most recent books have been featured in The Ormsby Review. See Robert Hogg’s review of On the Cusp of Contact: Gender, Space, and Race in the Colonization of British Columbia (Harbour Publishing, 2020, edited by Margery Fee); Duff Sutherland’s of Invisible Generations: Living between Indigenous and White in the Fraser Valley (Caitlin Press, 2019); Jamie Morton’s of Iroquois in the West (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019); and Michel Bouchard’s of Abenaki Daring: The Life and Writings of Noel Annance, 1792-1869 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016) (after whom Annacis Island in the Fraser River is named). Jean Barman has also reviewed I Am a Métis: The Story of Gerry St. Germain, by Peter O’Neil (Harbour Publishing, 2016) for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster