1023 On the Road to Damascus

Transatlantic Upper Canada: Portraits in Literature, Land, and British-Indigenous Relations

by Kevin Hutchings

Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020

$37.95 / 9780228001294

Reviewed by Graeme Wynn

*

Kevin Hutchings, the holder of a University Research Chair in the Department of English at the University of Northern British Columbia, begins this book with a very personal reflection. The decade and more that he spent working on it, he tells us on page one, “changed my understanding of who I am and what it means to be a member of Canada’s settler society.” This is no small thing, and Hutchings clearly hopes that others will be moved to experience a similar road to Damascus conversion by his series of “Portraits in Literature, Land, and British-Indigenous Relations” in Upper Canada.

Kevin Hutchings, the holder of a University Research Chair in the Department of English at the University of Northern British Columbia, begins this book with a very personal reflection. The decade and more that he spent working on it, he tells us on page one, “changed my understanding of who I am and what it means to be a member of Canada’s settler society.” This is no small thing, and Hutchings clearly hopes that others will be moved to experience a similar road to Damascus conversion by his series of “Portraits in Literature, Land, and British-Indigenous Relations” in Upper Canada.

Born in Montreal in 1960, raised in Burlington, Ontario, and educated at Guelph and McMaster universities after spending some time as a high-school drop-out, tree-planter, and itinerant musician in British Columbia in the 1980s, Hutchings became a student of the British Romantic movement. His doctoral dissertation and first book examined William Blake’s vision of Nature, and much of his early teaching focused on the works of leading Romantics, such as Lord Byron, William Wordsworth, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. With substantial numbers of Indigenous students in his classes in northern British Columbia, however, he recognized the importance of learning more about the Romantics’ views of Indigenous peoples and cultures, which were heavily influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s conception of people living in a pure state of nature. Through the first decade of the new millennium, he adopted the increasingly popular “transnational” perspective to examine transatlantic literary exchanges and to explore the role of “Romantic-era understandings of animality, climate, and habitat” in debates about “race, slavery, colonialism, and nature in the British Atlantic world.”[1]

Intrigued by the ways in which the Ojibwe author George Copway (Kahgegagahbowh) referred to Byron, Robert Burns, Walter Scott, and other leading Romantics in his 1850 autobiography, Recollections of a Forest Life, and alerted to the use of Romantic ideas in treaty-making efforts with Indigenous people by Sir Francis Bond Head, lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada in the 1830s, Hutchings began to notice connections and relationships among a significant number of prominent figures (Indigenous and newcomer) in Upper Canada and leading figures in the British Romantic movement. Believing that his previous scholarship might fruitfully be brought to bear on this little-discussed conjuncture of people, places, and ideas, Hutchings turned to interrogate the lives and literary works of large handful of British and Indigenous writers whose ideas intersected across the Atlantic. Hence this book – and its rich and interesting panoply of events and peoples.

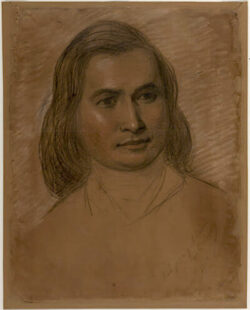

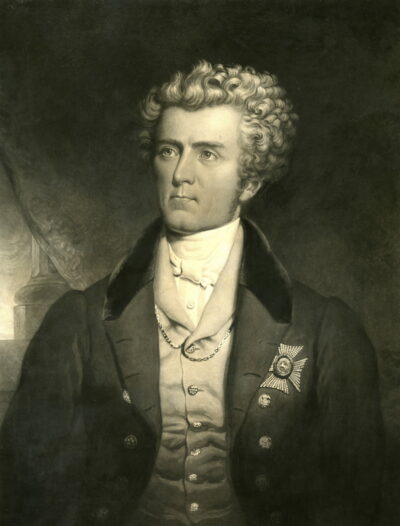

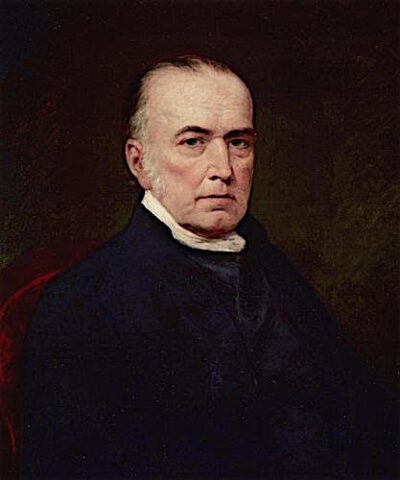

Hutchings builds his book around “key figures in Upper Canada’s transatlantic literary history,” focussing in the main on the “cross-cultural relationships, environmental philosophies and political activities” revealed in their writings (p. 27). The first three chapters portray British “settlers and sojourners” (p. 29). John Strachan and John Beverley Robinson, members of the Family Compact, are treated in separate chapters. Anna Brownell Jameson and Sir Francis Bond Head are dealt with together, characterised as Romantic memoirists, although they too were near the centre of colonial politics, one as the Crown’s representative, the other as the wife of Upper Canada’s attorney general and vice-chancellor. Four chapters are then given to “contemporary Aboriginal activists and their international diplomacy” (p. 29). Mohawk chiefs John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen) and John Brant (Ahyonwaeghs) — both of whom fought for Britain in the War of 1812 and advocated for the Haudenosaunee of Grand River in the colony and the UK – are the subjects of chapters 5 and 6. Ojibwe authors Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and George Copway fill out the portrait gallery. These depictions, inevitably somewhat dissimilar, are contextualized by a 28-page Introduction (“Literature, Land and Colonial Relations”) and a wide-ranging, not to say sprawling, 21-page reflection on “Romantic Ecology, Indigenous Culture, and the Ideology of ‘Improvement’” that forms chapter one.

None of those upon whom Hutchings turns his gaze are unfamiliar to historians of Upper Canada. Several have been the subject of full-length studies, all appear in the pages of The Dictionary of Canadian Biography, and many play significant roles in historical accounts of colonial development. But Hutchings is frank in acknowledging that his training is in literary studies, and this is where his contribution lies. By focusing on words rather than deeds – on what these figures wrote, on the literary influences that shaped the views they articulated, and on the ways in which their ideas intersected — Hutchings offers new and creative perspectives on the contributions of these reasonably well-known figures, even as he places aspects of the Upper Canadian story in a wider frame. In addition to turning up hitherto unknown or overlooked connections among otherwise familiar individuals, his exploration advances our understanding of how the intercultural milieu of Upper Canada fostered the hybridization of English Romantic and traditional Indigenous discourses in ways that attracted certain Indigenous writers to Romantic sentiments and underpinned a British Romantic fascination with Indigenous culture and beliefs.

Hutchings’ opening reflection tells us that he was moved to deeper reflection on the lives of his chosen subjects by the words of Justice Murray Sinclair and events surrounding the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report in Ottawa in 2015. That moment, he says (and few would disagree), “held glorious promise of how things might be.” Yet there was much “to learn from the past and even more work to do in the present.” He prayed for the “humility, strength and wisdom” to do his share (pp. xix-xxi). This I take as an honest assessment and an honorable commitment.

By my reckoning, Hutchings’ grasp of the complex continental, global, and imperial (as well as transatlantic) historical contexts of Upper Canadian development is somewhat under-cooked (perhaps understandably given the vastness of this field and his particular training). The “Native Question,” as it was sometimes known, was a topic of considerable concern in parliamentary and other circles in the United Kingdom. Many considered it the greatest moral question of their times. Several influential participants in the debate insisted on the imperative of “fair “exchange between colonizer and colonized: as one leading humanitarian had it, every effort should be made to ensure that Indigenous people receive, in return for their land and independence, “all the benefits of knowledge, civilization, education and Christianity that it is in our power to bestow.” They were outraged when Sir Francis Bond Head (newly-arrived – and over-promoted – as lieutenant governor) declared that Indigenous settlements in the southern parts of Upper Canada had failed to prosper, and recommended that people living in them should be relocated to Manitoulin Island where they could live free of the deleterious influence of white settlers. But in this, Bond Head was not a complete outlier. The situation was complex, rapidly evolving, and subject to many different interpretations. He essentially favoured the third of four alternatives that contemporaries envisaged as possible outcomes for Indigenous peoples: extermination; slavery; insulation; assimilation.[2]

In Upper Canada, Anna Jameson disapproved of the governor’s tendency (widely shared at the time) to regard Indigenous people as children of the Crown. There was little love lost between her and Francis Bond Head. Still, Jameson conceded that Bond Head was “sincerely interested in the welfare” of Indigenous people. Hutchings is less forgiving. In his assessment “good intentions cannot be allowed to excuse the damage perpetrated in the name of paternalism” (p. 136). In similar vein, Hutchings is loathe to concede that colonial officials’ early-nineteenth century dealings with indigenous people might have been “motivated by compassion rather than a desire for conquest” even as he quotes John Strachan to the effect that the Indians were brethren and that “humanity as well as religion requires something be done” for them (p. 61).[3] From his vantage in the third millennium, Hutchings may find Strachan’s views “arrogantly Eurocentric.” But it is the historian’s task to understand the past, not to indict those who lived then and there for failing to anticipate and comport themselves according to values that we, now, hold dear.

Hutchings also over-reaches, I think, in his effort to confer contemporary political relevance on his work. Writing in the shadow of the TRC, he is quick to find parallels between early- nineteenth and twentieth-century events. Discussing Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Bamewawagezhikaquay) in his first chapter, he notes that she delivered her two children to boarding schools in the eastern United States “to become Europeanized citizens (just as Canada’s residential schools would begin systematically doing to thousands of Indigenous children several decades later).” This is perhaps a little glib, especially against widespread perceptions of children torn from homes to enter the Canadian residential school system, as portrayed in Kent Monkman’s painting “The Scream.” Schoolcraft left her children reluctantly — “With a sober regret, and a bitter farewell” according to the free translation of a poem she wrote in Ojibwemowin – but she did so voluntarily. No doubt Jane Schoolcraft felt a mother’s emotional angst at leaving her young children behind, but (as Hutchings’ text makes clear) the heart-rending sentiment of the translation, published years after her death by her white American husband, the ethnographer and Indian agent Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, is substantially muted in the Ojibwemowin version (pp. 45-6).

Bethany Schneider, a student of nineteenth century American literatures, provides an interesting interpretation of this shift, with the argument that “Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s translation papers over the transition between Indian and white sovereignties” to produce “an uninterrupted, neatly teleological journey from Indianness to whiteness….” In her view, Henry’s version of the poem draws a clear line between a Native American past and a white future that Jane “born of a much more complicated world,” refused to countenance. Her version of the poem presented space and time as “synchronic, overlapped, [and] interpenetrating,” as she resisted the “streamlining and simplifying [of] people, land, gender, and nation” by the juggernaut of early nineteenth century change.[4]

As this comment suggests, Hutchings’ book engages with a fascinating, important and enormously complicated set of characters and circumstances. Jane Schoolcraft grew up in “a radically intercultural world” – “a métis world, ‘the middle ground,’ that was neither red nor white in the way those concepts later came to be understood.” She married a man who was a prominent agent of the changes that remade that very world. Born and raised in Scotland, Strachan was an educator, churchman and defender of tradition through tumultuous periods of change and reform in Upper Canada. Robinson the Quebec-born son of a Virginia Loyalist, a strong supporter of immigration and development, was a Tory Anglophile. Bond Head, a socially conservative English-born, military man, author, and “damned odd fellow” had “a romantic yearning for the hero’s role.” Peter Jones was the son of a Welsh-born land surveyor and the daughter of a Mississauga chief. He converted to Methodism at a camp revival in his early 20s and then married the intensely-religious daughter of an affluent English family. John Norton, the child of a Scottish mother and Cherokee father, was born and schooled in Scotland. He enlisted in the British army, came to Canada as a soldier, deserted, and served the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel as a schoolteacher at a Mohawk settlement before becoming a fur trader out of Detroit, an interpreter for the Indian department at Niagara, Upper Canada, and (after a visit to London early in the 1800s) a missionary for the British and Foreign Bible Society.[5] And so on.

Borrowing a phrase from the American historian Alan Taylor, Hutchings acknowledges that the subjects of his inquiry occupied “a porous borderline of shifting identities,” and indicates that he hopes to illuminate the “fullness of their lives and writings” by considering them through a transnational lens focused on transatlantic interactions and influences. For literary scholarship this means approaching texts as “complex manifestations of international or cosmopolitan dialogue,” being interested in “processes of intertextual negotiation and interchange,” and attending to the “various points of friction…where discourses intersect” (pp. 11-13). By these means, Hutchings aims to recognize European and Indigenous writers as “active agents negotiating complex sets of relations.”

By considering his chosen cast of characters alongside one another, and in this way, Hutchings does cast them in a fresh light. This is, indeed, a welcome achievement. But I am less sure about the distinction between British (settler) and Indigenous perspectives that threads through these pages. Yes, categorization is essential for the successful navigation of complexity: we need to be able to talk of “trees” and “grasses” rather than endlessly listing the names of species. But to categorize is, inevitably, to abstract, to bundle together somewhat different individual entities under a single label. People are complicated. Their ideas shift and their words and deeds are not always consistent one with another or over time. To my mind, those whom Hutchings “portrays” are not archetypes but intriguing individuals attempting to make their imperfect ways through a fast-changing world, the contours of which they only partly discerned. Their very diversity emphasizes the perils of streamlining and simplifying lives and arguments. The more we reduce complexity the greater the loss of detail and nuance. Categories essentialize. As they resolve toward binaries (Us-Them/ Ours-Theirs), they almost inevitably reduce the chances of identifying overlaps and the prospects of finding the common ground that we so desperately need.

*

Graeme Wynn is Professor Emeritus of Geography at UBC. As an historical geographer and environmental historian, he served that institution in various capacities including Associate Dean of Arts, twice as Head of Geography and, for six years, as editor of BC Studies. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, he served as President of the American Society for Environmental History (2017-2019) and he is Adjunct Professor (History) in the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Wynn currently serves on the Advisory Board of The Ormsby Review, on the Advisory Board of UBC’s Green College, and as Principal of UBC’s Emeritus College. Much of his work has focused on Canada, although his interests extend more broadly to encompass much of the so-called British world. He edits the Nature|History|Society series published by UBC Press, and in 2019, under the On Point imprint of UBC Press, published a collection of essays, co-edited with Colin Coates, The Nature of Canada, reviewed for The Ormsby Review by Jenny Clayton. Editor’s note: Graeme Wynn has also reviewed books by Alison Wearing, Robert William Sandford, Edward Burtynsky, Jennifer Baichwal, & Nicholas de Pencier, Alejandro Frid, Adam Shoalts, Alfred Siemens, and Robert Griffin & Richard Rajala for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Kevin Hutchings, Romantic Ecologies and Colonial Cultures in the British Atlantic World, 1770-1850 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009)

[2] See my “Strains of Liberalism,” Foreword to David Calverley, Who Controls the Hunt? First Nations, Treaty Rights and Wildlife Conservation in Ontario, 1783-1939 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018), pp. ix-xxiv for more on this.

[3] Kevin Hutchings, “Cultural Genocide and the First Nations of Upper Canada: Some Romantic-era Roots of Canada’s Residential School System,” European Romantic Review, 27, 3 (2016), pp. 301-08

[4] Bethany Schneider, “Not for Citation: Jane Johnston Schoolcraft’s Synchronic Strategies,” ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance, 54, 1-4 (2008), pp. 111-144

[5] See entries in Dictionary of Canadian Biography for each of those mentioned except Schoolcraft (quote is from Schneider, “Not for Citation,” p. 114 citing Robert D. Parker, ed., The Sound the Stars Make Rushing through the Sky: The Writings of Jane Johnston Schoolcraft, (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), p. 4

One comment on “1023 On the Road to Damascus”