Frederick Paget Norbury: Introduction

ORMSBY REVIEW PRESS: Introduction to Frederick Paget Norbury, Remittance Man or Gentleman Immigrant? The Story of an Englishman in Canada

by Brenda Callaghan

*

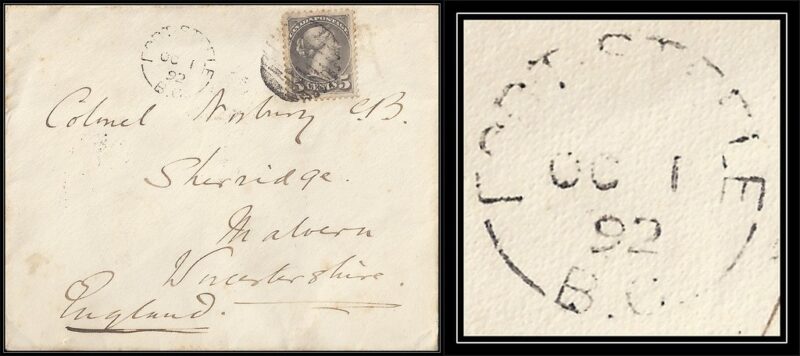

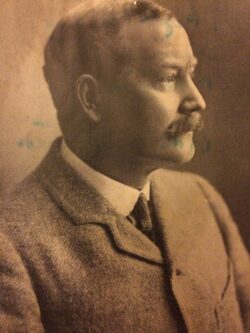

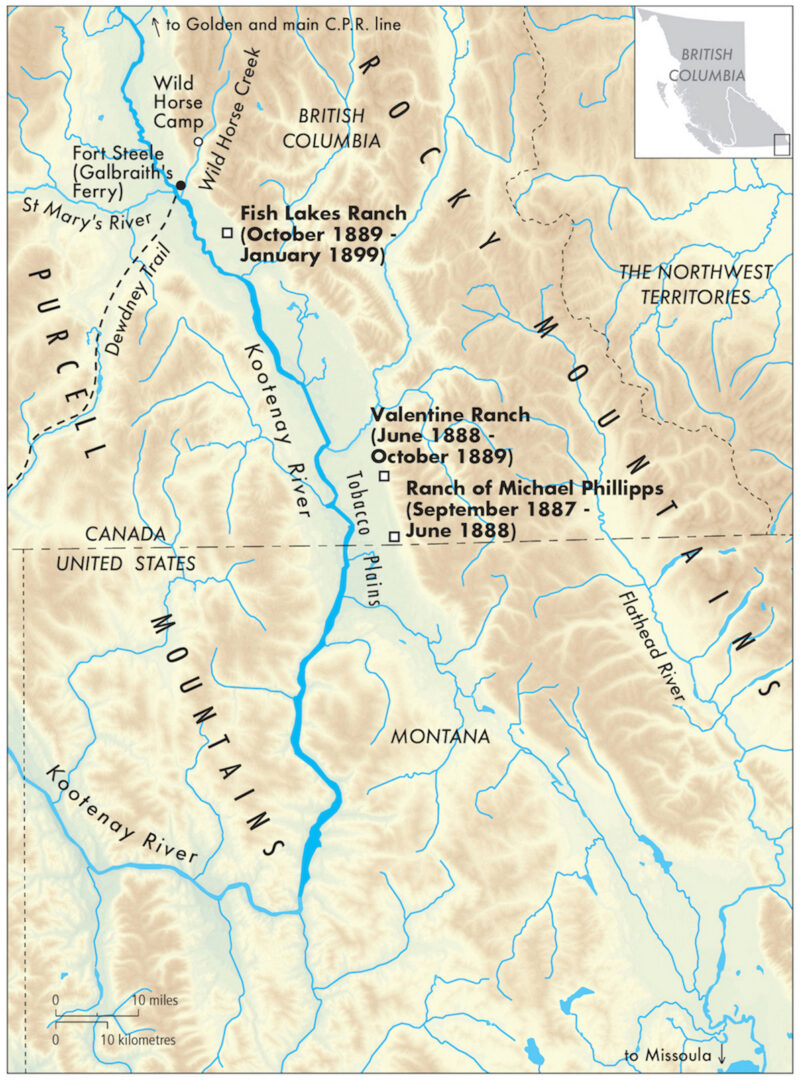

Editor’s note: We are pleased to present the first instalment of the late Brenda Callaghan’s biography and selected correspondence of East Kootenay settler Frederick Paget Norbury (1867-1940). In 1887, Norbury became one of the first immigrants to travel west to British Columbia on the newly-completed Canadian Pacific Railway, and he would stay in the Fort Steele area for ten years, acting as rancher, Justice of the Peace, Stipendiary Magistrate, and Special Constable.

In 1898, Tommy Norbury returned home to Sherridge House, his family’s country house just outside of the village of Leigh in Worcestershire, England, to help manage the family estate, which he would take over in 1914 on the death of his older brother.

Sadly, Brenda Callaghan died in 2o18 before she could see the book published in The Ormsby Review Press. Please see her biography at the foot of this page. Her full 135,000-word manuscript of Frederick Paget Norbury, “Remittance Man” or Gentleman Immigrant? The Story of an Englishman in Canada, will be published here in instalments over the coming months.

We thank Brenda’s husband, Tim Gould, and her daughter, Natasha Schorb, for the opportunity to publish Frederick Paget Norbury online in The Ormsby Review Press. — Richard Mackie

*

Introduction

The Norbury letters lie at the heart of this work. A selection of them is reproduced here with minimal alteration. The repository of family letters first came to my attention when I visited the Fort Steele Archives in the East Kootenay area of British Columbia, close to where I live. They had been loaned to BC Parks for copying some years earlier by the Norbury family, who live in England, and they had been handed on to the Archives. It seemed to me that they represented a very important contribution to the historiography, not only of the East Kootenay, but of the province of British Columbia as a whole, and I felt it was important, not only to tell the story of the letter-writer, but also to make at least some of his letters available to a wider audience.

Frederick Paget Norbury, the writer of the letters featured here, was known as “Tommy” to his family, probably because both his father and grandfather were named Thomas, and he invariably signed himself “Tommy” when writing to his nearest and dearest. In the following discussion I will refer to him both as “ Tommy” and “Norbury”. He was one of eight siblings, and was well-educated and highly literate. Like some of his close relatives, who distinguished themselves in the literary field, he had a flair for writing. The letters were sent regularly over an eleven-year period, and represent the main means of communication between Tommy and his family in England during his sojourn in BC. Most letters were addressed to Norbury’s parents, although he sent several to his elder brother Coni, and a few to his older sisters: Florence, Nell, Win and Betty. (We do not know if he ever wrote to Kitty, but she was married, so any letters surviving in England may have passed beyond the immediate Norbury family, and have been stored, if they were kept at all, at her husband’s home).

Being of English extraction myself, and familiar with certain English expressions, I occasionally found it necessary to correct inaccuracies in the transcriptionists’ interpretation of English idiom. This is certainly not intended as a criticism of the transcriptionists’ praiseworthy efforts, and all who use the Norbury letters in the original or as they are reproduced here, will be indebted to the staff at the Archives for making accessible this valuable record of a bygone age.

In their entirety, Tommy Norbury’s letters tell the story of a young immigrant who lived in the East Kootenay between 1887 and 1898. Most of them were penned by Norbury himself, although a handful were written by his brother Billy, and some are from related sources. The complete collection of transcriptions may be viewed either at the Fort Steele Archives, or at the Provincial Archives in Victoria, and the manuscript collection at the Provincial Archives only.

Tommy Norbury arrived in the East Kootenay with the intention of ranching. He was supported in this endeavour with funds or “remittances” that he received regularly from his parents back in England. This was not an uncommon practice in the nineteenth century, when many young men from upper-class backgrounds were sent out to New Zealand, Australia, Canada and other parts of the British Empire to make new lives for themselves. Unable to make a living in England, they were frequently the second sons of landowners, with little or no expectation of inheriting the family estate. Too often, desperate parents of wayward sons packed them off to “the colonies” in a last-ditch attempt to force them to shift for themselves and “turn over a new leaf” beyond the prying eyes of family friends and neighbours. The wilds of Canada could be a convenient solution to an embarrassing problem. And if this strategy failed, Canada could serve as a convenient “dumping ground” for the really hopeless cases. Sometimes.

Some of these young men did well. Some did not, and they were eventually ridiculed for their air of superiority, their lack of business acumen, their dearth of practical know-how, or their overall incompetence. There can be little doubt that many such young men who made their way to Canada were completely unsuited to their new environment. As these letters will reveal, Tommy’s own brother, Billy Norbury, was one such immigrant.

But it would be a gross misrepresentation to claim that all upper-class Englishmen were destined to make utter fools of themselves in their pioneering attempts; and it would be wholly inappropriate to suggest that Norbury fell into the typical “remittance man” category. These letters tell a very different story. Although the “remittance man” stereotype holds a great deal of popular (and populist) appeal, and certainly characterizes a goodly number of upper-class male immigrants who were unsuccessful in their attempts to settle in their new homeland, it can be misleading. It deflects attention from the long tradition of “gentlemen immigrants” who quietly distinguished themselves by their successful adaptation to Canada and who made valuable contributions to Canadian society. Tommy Norbury was one of these.

*

It is my hope that the letters presented here will impress the reader, not only with their wit and literary polish, which invites one into the world of the writer, and encourages one to linger and savour this forgotten world, but also their length, and the obvious commitment which the writing of such missives demanded. Norbury appears to have been a devoted, dutiful son, and considerate of his parents’ feelings and expectations. He wrote every few weeks, despite the busy-ness of a very full life, which didn’t appear to be an impediment to his literary exertions. One wonders how on earth he managed to find the time to turn out all these detailed accounts of his daily existence!

In our era of instantaneous electronic communication, the writing of letters may appear as a quaint, even a redundant pastime; yet it carried supreme importance in the nineteenth century, especially for families who were separated by distance. In fact, the writing of letters has been understood by some historians as one of the chief methods by which the vast British Empire was held together. It was very common for letters, with the inclusion of sketches or the odd photograph, where possible, to be written regularly and often between new immigrants to Canada and their families back in the “Old Country.” At a time when emigration was becoming popular, they were a vital means of keeping together the family unit, at least at the level of emotion. For the immigrant, far away from all that was known and familiar, not only could they provide a large degree of comfort and security, they helped bolster values imported from home, and guarded against loneliness. For the family back in the country of origin, they helped keep the loved-one close in imagination, they provided reassurance of their wellbeing, and allowed the family to participate, vicariously, in the experiences of the migrant. Letters might facilitate what has been called “chain migration;” that is, by making relatives more immediately aware of life overseas, letters written home by nearest and dearest might serve to encourage other members of the same family to also take the step to settle abroad. There was a great deal of security to be had from knowing that one’s own kin had gone before — and survived.

Letters could also be a conduit for the exchange of valuable information. Families back home worried about what they perceived as the “wild,” unsophisticated lives their family members were now leading in an alien part of the world, and the inherent dangers of this type of existence. Life was certainly different, and the magnitude of that difference was something that many families could find hard to comprehend.

A large majority of settlers in British Columbia were, like Norbury, single males. Often such young men were living outside of a family situation for the first time in their lives. Many would never return to England. If they were not entirely alone, they might find themselves sharing households with other single males. Lacking the comforts and conveniences of domestic life, such men often crossed gender boundaries to learn and perform household skills which, in their homeland, would have been the exclusive preserve of women. It was often necessary, for example, for bachelors to learn how to cook, and worried mothers sent much-appreciated advice on basic cookery and easy recipes. As we shall see, Norbury’s mother was no exception. She responded to her son’s enquiries with evident maternal concern, and offered him much valuable domestic advice. It is difficult, therefore, to over-emphasize the importance of letters to both immigrant and family. They were effectively a practical and emotional lifeline. Hence the concerns, which come out so clearly in the letters, about the tardiness and unreliability of the mail service.

These letters also have much to tell about the history of a particular region of Canada, and the importance of immigration in the settling of that specific area. We are able to learn a great deal about the development of the East Kootenay through the personal insights of someone who experienced that history firsthand. Norbury’s letters describe, often in close detail, the daily life of the pioneer rancher, and the challenges faced by settlers in a remote, sparsely populated part of the province. We learn of the difficulties of transportation and of obtaining basic commodities, of the unreliable mail service, and of the hard physical work required to build and maintain a home in the wilderness. Yet we are made constantly aware of the pristine beauty of the land, of the camaraderie between Norbury and his close friends, his sense of freedom, and over time we see life becoming less gruelling as the area develops and changes.

The chief value of the letters, however, has less to do with highlighting the personality and experiences of one particular individual, living in a particular area, at a particular time, than it has to do with helping to construct a far broader picture. What happened to Tommy Norbury was not unique. The challenges he encountered, the hardships he endured and the satisfactions he enjoyed, were typical of those experienced by many of the early settlers of late-nineteenth-century British Columbia. And if his privileged social position provided him with certain advantages over his Canadian counterparts, nevertheless, his East Kootenay sojourn also opens a window into the large-scale immigration to western Canada of educated and sometimes privileged British settlers of the late nineteenth century — settlers who played a particularly important role in the early development of British Columbia.

*

In order to more fully understand the Norbury letters, we need to know something of the context in which they were written. Chapter One, therefore, begins with an overview of the history of the East Kootenay, the area in which Norbury took up residence when he arrived in Canada. It looks at the nature of the region and its economic and social development, and discusses such things as mining, transportation and the growth of settlement prior to and at the time of Norbury’s arrival, as well as the attitudes of the original inhabitants and later arrivals. Chapter Two examines Tommy’s family background as well as the reasons for his migration in the first place, noting factors on either side of the Atlantic which served as motivators for his decision to migrate, and discussing immediate family reasons as well as broader trends in society at large. Chapter Three presents the letter themselves.The letters tell Norbury’s story of his journey to Canada in his own words, and document his arrival in BC, his time spent in the East Kootenay, and his eventual departure over eleven years later. His time in the area falls into four discrete periods: the brief time he spent “settling in” at the Phillipps ranch, familiarising himself with the area while he made plans for his future; his doomed attempt to run his own ranch with his younger brother, Billy; his more successful but ultimately short-lived partnership with Parker, which taught him a great deal about the ranching business; and finally the years from 1894 spent operating a cattle-ranch as his own boss before his return to England in 1899.

Although largely concerned with interpreting and analysing Nobury’s letters, the discussion following them (which constitutes Chapters Four, Five and Six) not only analyses his skills and the aspects of Norbury’s personality which caused him to succeed in his ranching endeavours, contrasting them with those of his less talented brother, but it contextualises the story by drawing heavily from the published work of the travel-writers Lees and Clutterbuck, who made the same journey as Norbury at about the same time, and later from newspaper articles which documented aspects of Norbury’s life at a time when he had become, to an extent, a public figure. The Conclusion draws together the main themes presented here, and the Epilogue uses family sources and newspaper articles to briefly sketch the remainder of Norbury’s life in England.

Acknowledgements

In preparing this work, I have been assisted by a number of people. I would like to thank the staff past and present, at the Fort Steele Archives, in particular Kristin Schachtel and Derryll White, also Naomi Miller for reading an early draft of one chapter, and showing me around Fort Steele and the Fort Steele Cemetery, Susan Campbell at the Worcester Record Office who went out of her way to be of assistance, and Peter and Tom Norbury, of Sherridge House, Worcestershire, England, who were invaluable in helping to fill in many gaps in my knowledge. I am also indebted to the staff of the Invermere library and the Victoria Archives, and many friends and neighbours who were so helpful and encouraging, notably Doreen Murray. Beverley Coulter, and Felicity and Mohsen Enayat. My daughter, Natasha Schorb, read an early version of the text and made some valuable and intelligent suggestions, and Richard Mackie lent his expertise and undertook the arduous task of critiquing an early draft and giving much valuable advice, editorial help and support. Most of all I would like to thank my husband, Tim Gould, whose understanding of modern technology far exceeds mine, and without whose help this work would never have appeared in print.

*

Brenda Callaghan, 1951-2018. Brenda Callaghan was born in Barrow-in-Furness, a small industrial town in the English county of Cumbia, in 1951. In defiance of local convention, Brenda remained in high school to earn A-levels and subsequently entered teacher training college, at what is now Leeds Beckett University, in 1969. Brenda’s teaching skills allowed her to immigrate to Canada in 1975 and eventually to fill teaching posts in Prince Rupert and Kitimat. Shortly after her daughter Natasha’s birth, Brenda’s first husband fell ill and left Brenda widowed in 1981.

Brenda returned to academic studies in 1984 and over the following years was awarded a BA (Hons), an MA, and a PhD from the University of Victoria’s Department of History. Strongly affected by the loss of Natasha’s father, Brenda’s graduate and post-graduate research explored the cultural significance of customs associated with birth, death, and marriage in England’s post-industrial north.

It was while conducting this research that Brenda met her second husband, Tim Gould, in Cumbria in 1991. During and following the completion of her PhD in 2000, Brenda worked as a sessional instructor at UVic and England’s Open University. In Cumbria, Brenda’s research was of broad public appeal and in the 1990s she established a reputation as an engaging guest speaker at local history societies. After settling with Tim in the East Kootenay region of BC in 2002, Brenda followed her interest in local history to the nearby Fort Steele Museum and Archives. It was there that Brenda, with the help of the curatorial staff, unearthed the letters of Frederick Paget Norbury.

Brenda was no stuffy academic. Widely travelled, she saw much of Europe, North America, and the South Pacific. She ran a successful Bed & Breakfast in the Canadian Rockies, enjoyed live music and the theatre, was a scuba diver, keen hiker, and skier, and to the surprise of many, an enthusiastic long distance wilderness paddler.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

8 comments on “Frederick Paget Norbury: Introduction”

It’s great to be able to share these pages with my children! I am encouraging them to explore their family history back in the old country. I also have letters to and from my great grandfather, Michael Phillipps.

Can’t wait to pour over this fascinating bit of history from my home region!

Hi Dan and other readers, I keep posting chapters of this story. So far in 2021 I’ve posted Chapter 1, Chapter 2, and Chapter 3. Enjoy! — Richard Mackie

This book emphasizes how important a collection of letters is to assist recording history.

However, since so many emails are soon deleted, what references can be used in future years?

I am so looking forward to reading this work.

Such a good question, Tom! I think local and BC historians should preserve their most important letters in hard copy — I mean print up their most important email and keep a file of it somewhere. It seems permanent, but this digital house of cards could possibly collapse one day.

I think local and BC historians should preserve their most important letters in hard copy — I mean print up their most important email and keep a file of it somewhere. It seems permanent, but this digital house of cards could possibly collapse one day.

Hi Peter Flynn and other readers, I keep posting chapters of this story. So far in 2021 I’ve posted Chapter 1, Chapter 2, and Chapter 3. Enjoy! — Richard Mackie