#939 The path to regeneration

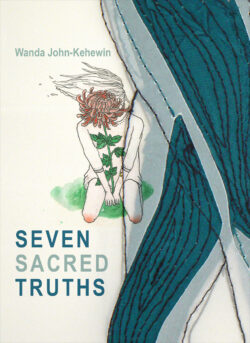

Seven Sacred Truths

by Wanda John-Kehewin

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2018

$18.95 / 9781772012132

Reviewed by Savana Alphonse with Rebecca Fredrickson

*

Seven Sacred Truths offers an unfettering of writing styles, including prayer, poetry, prose, and letters, that reflect Wanda John-Kehewin’s personal exploration of self through a healing journey. The title relates to what Indigenous people know as the “Teachings of the Seven Grandfathers,” “Seven Sacred Teachings,” or related versions. These teachings set out what is required to live a full and healthy life and guide our conduct towards others, Mother Earth, and ourselves. As she travels the trails of inner exploration, John-Kehewin shares with us her interpretation of the Seven Sacred Truths or Teachings, which (simply put) are: to know love is to know peace; to honour all of creation is to have respect; to have bravery is to face the foe with integrity; to practice honesty also means to practice righteousness; honesty must begin with yourself, in word and action; humility is to know yourself as a sacred part of the Creation; and Truth is to know all of these things. The writing in Wanda John-Kehewin’s latest poetry collection passes these teachings on to us so that we experience them in relation to contemporary Indigenous issues.

Seven Sacred Truths offers an unfettering of writing styles, including prayer, poetry, prose, and letters, that reflect Wanda John-Kehewin’s personal exploration of self through a healing journey. The title relates to what Indigenous people know as the “Teachings of the Seven Grandfathers,” “Seven Sacred Teachings,” or related versions. These teachings set out what is required to live a full and healthy life and guide our conduct towards others, Mother Earth, and ourselves. As she travels the trails of inner exploration, John-Kehewin shares with us her interpretation of the Seven Sacred Truths or Teachings, which (simply put) are: to know love is to know peace; to honour all of creation is to have respect; to have bravery is to face the foe with integrity; to practice honesty also means to practice righteousness; honesty must begin with yourself, in word and action; humility is to know yourself as a sacred part of the Creation; and Truth is to know all of these things. The writing in Wanda John-Kehewin’s latest poetry collection passes these teachings on to us so that we experience them in relation to contemporary Indigenous issues.

John-Kehewin is an Indigenous poet, of Cree and Métis ancestry, from Kehewin, Alberta. Her poetry has been widely published, and in 2018 she won the World Poetry Foundation’s Empowered Poet Award for her collection In the Dog House (Talonbooks, 2013), which she describes as a “healing journey.” Seven Sacred Truths is a follow-up to that journey. The very fact that John-Kehewin has written this book about her trauma demonstrates her bravery. The honesty in her writing requires great courage, humility and love — all sacred truths. She follows these truths in her writing, and these truths make her book a therapeutic medium, a zone of integrity and strength within which we might deal with the colonial traumas that have historically affected Indigenous people and continue to do so. John-Kehewin invites us into the volatile emotional experiences of trauma and allows us to share it with her while also guiding us on her healing journey.

As an Indigenous woman, I can relate to the colonial trauma that John-Kehewin demonstrates so powerfully throughout Seven Sacred Truths. I felt sad or frustrated after reading “BROTHER,” her poem that tells a story of family separation through the author’s distinctive interplay of story, lineation, and typography. This interplay casts a confluence of emotions from sorrowful nostalgia to troubled confusion, before ultimately coalescing into a highly charged and complex experience subject to the reader:

TRying TO mufflE puppy sOunds. yOuR THumb lEfT OuT.

By THE sidE Of yOuR small BERRy mOuTH.

yOuR pincHEd facE. wET wiTH salT. dRiEd snOt.

fROm yEsTERdaY. yOuR haiR sTanding Tall.

fREshly cuT By sTRangERs.

nO mOTHER tO cOmB it (pp. 59-60).

These short lines describe, with sensory images, a small child — a brother — who is alone and suffering. The lines are consistently end-stopped, creating a visual and sonic choppiness that reminds me of the heavy sobs of my childhood: the loud, deep breaths, followed by uncontrollable hiccups that made speech nearly impossible to perform. Additionally, each instance of the letters that comprise the word “BROTHER” is capitalized, and this typography adds to the embodied emotion I experience while reading this poem. At first, I found the capital letters confusing and frustrating, but as I spent more time with it, I understood that the uncomfortable effects of John-Kehewin’s typography connect me with the poem’s speaker and the confusion and frustration a child would feel under traumatic circumstances.

The poem’s typography also reflects the speaker’s inner world because, while it might not be immediately visible, the word “BROTHER” infuses every line of the poem. Even the “sTRangERs” who have cut the boy’s hair are, in the eyes of the speaker, overshadowed by the power of “BROTHER.” For me, then, the typography emphasizes the overwhelming personal toll that separation from her own brothers — through the foster care system — had on Wanda John-Kehewin. In this particularly moving piece, she has managed to show us how powerful love can be. Her love for her brother encompasses bravery and honesty. Her love can transcend time and institutions.

Seven Sacred Truths carries a variety of perspectives. While “BROTHER” conveys a sorrowful child’s point of view, “Letter to My Nine-Year Old Self” suggests a more mature outlook. Written in the style of a letter, it seems to be an apology to an inner child. Each time I return to this poem, I find that I am experiencing it rather than just reading it. This affective engagement makes me reflect on my relationship with my own inner child. The sorrow, confusion, and frustration I feel in relation to this poem remind me that honesty begins with the self. In Seven Sacred Truths, John-Kehewin explores her past, and even has conversations with her child-self, while confronting issues honestly. The act of taking responsibility for your own healing is a step towards self-governance. The path to healing is full of pain from wounds past, but John-Kehewin guides us through colonial traumas towards a present that is grounded in acceptance and love.

Within every Indigenous person is an Indigenous child who has had to face the traumatic fallout of colonialism. “Letter to My Nine Year Old Self” is an affirmation that provides the words that a child surviving amidst colonial trauma has a right to hear. Or rather, has a need to hear — for the first victims of this world are the children. The author concludes the letter with these words of endearment to her child-self: “I can tell you that every thought and experience you had has shaped you into an absolute empath. I can tell you I am sorry for humanity and that I love you” (p. 109). On the healing journey, we must work with our past so as to work with our future. “Letter to My Nine Year Old Self” is a poem of acknowledgement, acceptance, apology, and ultimately a profound expression of unconditional love. John-Kehewin’s honesty and humility with her younger self is a true display of respect that we should all hope to achieve.

Along with the chaotic tragedies that come with the storm clouds of colonialism, there is always a resilient silver lining. Wanda John-Kehewin is an exemplary Indigenous woman whose writing is an example of that resilient silver lining left behind by the tempest of colonial institutions.

*

Savana Alphonse writes: “I’m a 27 year old Indigenous academic with blood ties to the Tsilhqot’in and Nehiyawewin peoples. I am the youngest of my siblings and the only girl. My parents are Grant and Angela Alphonse, both of whom are survivors of colonial trauma, my father of a Residential School and my mother of the Sixties Scoop. My parents have degrees in education and law, and they draw from their formal educations (and from their experiences of growing up) as they teach their children to examine and discuss the effects of colonialism and the actions and processes of decolonization. As a university student I aim to explore the vast expanses of my creative knowledge and inheritance. I am steadily searching for ways to break the chains of colonialism that shackle my Indigeneity.” Rebecca Fredrickson teaches English and Creative Writing for Thompson Rivers University, at the Williams Lake campus, which is located on the unceded lands of the T’exelcemc and within the traditional territory of Secwepemcúl’ecw. Rebecca’s goal as an undergraduate mentor, and as a co-writer for The Ormsby Review, is to help students gain the skills they need to envision and create their own unique styles and writing practices.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster