#915 Shutting down parliament, 1970

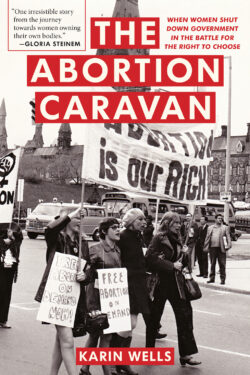

The Abortion Caravan

by Karin Wells

Toronto: Second Story Press, 2020

$24.95 / 9781772601251

Reviewed by Donalda Reid

*

Karin Wells has written an engaging book, The Abortion Caravan, about the 1970 national women’s march on Parliament aimed at forcing changes to Canada’s abortion laws. Her book takes us back fifty years into a period of heightened social change, of protests and marches against the Vietnam War in Canada and the US, and growing demands in Canada for equality and women’s rights. Wells documents the cross-country trek when a group of seventeen young women from British Columbia acted on the idea that to make any changes in a woman’s rights and access to individual freedom, they would have to get the attention of the government and force them to make changes. Abortions were the focus of the march, but the broader issue of women’s rights fuelled the Caravan’s momentum.

Karin Wells has written an engaging book, The Abortion Caravan, about the 1970 national women’s march on Parliament aimed at forcing changes to Canada’s abortion laws. Her book takes us back fifty years into a period of heightened social change, of protests and marches against the Vietnam War in Canada and the US, and growing demands in Canada for equality and women’s rights. Wells documents the cross-country trek when a group of seventeen young women from British Columbia acted on the idea that to make any changes in a woman’s rights and access to individual freedom, they would have to get the attention of the government and force them to make changes. Abortions were the focus of the march, but the broader issue of women’s rights fuelled the Caravan’s momentum.

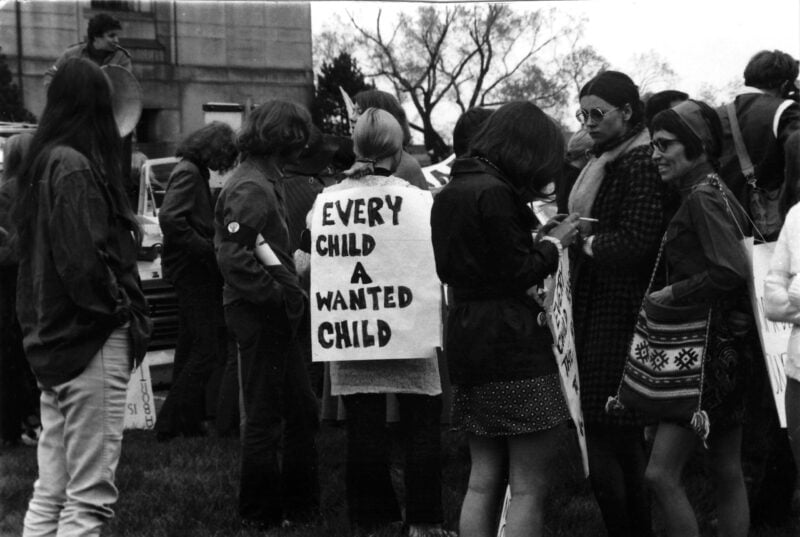

Their four main issues were access to child day care, workplace and pay equality, access to workplace education, and reproductive rights. Abortion was chosen as the issue most likely to have the broadest appeal, writes Wells: “It cut across party and class lines. It had a profound personal impact on women and indirectly men; it was an issue for young women with their lives in front of them; for middle-aged women with a passel of children and no money for more; for rural women, city women, and … for women of every race and ethnicity.” It was an issue for all Canadian women across all provinces, not just for the young women who made up the members of the caravan.

The first nine chapters follow the caravan’s progress from Vancouver to Ottawa. The text, however, is not a sequential travelogue. Using the who/what/where/when/why and how of good journalism, Wells weaves a richly written, personal history of the women through and around their route, their lives before they joined the caravan, the dynamics of their political interactions, their differing philosophies and how they came to hold them, and how they came to be part of the caravan. She details the political makeup of the governments of each province they passed through and how attitudes toward women affected the caravan’s hope of forcing the federal government to allow abortion on demand. The book is as much a history lesson as it is about the caravan itself – a lesson in Canadian politics, the main political characters who influenced attitudes affecting women, the growth of social awareness, the spread of feminism and female independence, and the contemporary and commonly held attitudes to pregnancies and abortions.

The caravan’s route forms the backbone of the book’s organization. Laid over its bare spatial framework is a detailed, informative, interesting, and almost encyclopaedic wealth of important information that solidly fleshes out the story. When Wells steps away from the travelling to give us essential information, she returns us to the same spot on the road, and from there the journey carries on again eastward. Descriptions of places through which they drove give us a sense of place and bring the country alive. Although we are reading about the caravan, we are being shown Canada in 1970, complete with all the barriers that women faced.

Wells begins on the morning the caravan set out from Vancouver to Ottawa in eye-catching vehicles. We learn the political history in British Columbia under the Social Credit (Socred) government, the establishment of SFU as BC’s second university, and the student radicalization that ensued. She describes the support network that provided and circulated information and assistance in accessing illegal abortions in Vancouver during the pre-caravan period. From the beginning of the journey, the women organized themselves collectively, alternating roles and cementing decision-making by consensus, something they maintained through the whole caravan.

For each section of the country on their eastward trip Wells provides the political history, socio-economic makeup of the cities, and how the difficult issue of access to abortion was dealt with in each place. Along the way they held rallies, meetings, lectures, guerrilla theatre, press conferences, and parades organized by local women’s liberation groups in each city they stopped. Everything was ready — meetings organized and advertised, places to stay provided. They most often slept in sleeping bags on church basements or on the living room floors of volunteers’ homes.

As they pulled into a city — Kamloops, Calgary, Edmonton, Regina, Saskatoon, Thunder Bay, Toronto, Ottawa — their Volkswagen van, convertible, and truck announced their purpose: abortion on demand. Constantly under the surveillance of the RCMP and Ontario Provincial Police, their group grew in size. By the time they reached Parliament Hill they were close to five hundred strong.

Many things we take for granted today, including Medicare and legal abortions, were enough in 1970 to brand you as a “leftist” or communist. Every move the women made was recorded by the RCMP in secret surveillance. The women of the Abortion Caravan were the domestic terrorists of the day. In Saskatchewan — where the party of the social democratic CCF (since 1961, the NDP) was instrumental in getting government-funded Medicare passed — the caravan had the strongest local support. The phrase “right to choose” was first used in Saskatoon.

Their invasion of the Houses of Parliament — and how they shut down Question Period, forcing the first and only closure of the Canadian Parliament, and their subsequent escape without any arrests — needs to be read to be believed. Though they weren’t able to meet Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, they shut down the seat of government in Canada.

Were they successful in changing access to abortion? In the short term, no. But their journey was not a failure. It represented a clear and pointed beginning toward more personal control for women. Though they weren’t able to get the Liberal government of the day to make abortion freely available, they did force the topic out in the open. As Jackie Larkin, one of the BC women, recalls, “Amazing — shutting down the Houses of Parliament. It’s no small feat, and we put the abortion issue smack in the middle of the debate.” The gruesome facts of women dead or maimed had become public: “…one woman died every four hours after an illegal abortion; twenty thousand annually required hospital care; and abortions affected one in four families in Canada” (p. 150).

It was only in 1988, eighteen years later, that the Supreme Court of Canada ruled the provisions regarding abortion were unconstitutional and removed them from the Criminal Code.

In her author’s note Karen Wells confesses she “missed” the Abortion Caravan on 1970. So did I. As a twenty-something woman, I had been on birth control pills during university. I worked in the Education Faculty at SFU in 1968/9 while student protests were taking place there, and I was unaware of the background details, drama, and import described in this book. I knew students had taken over areas of the campus, but in our little education huts tucked away from the main buildings, I was oblivious to the main events. I had minimal knowledge of what these remarkable women did. Perhaps it was the newspaper strike in BC at the time that limited general information about the caravan as it traversed Canada.

It’s been fifty years since they marched, but many issues the caravan women listed as concerns limiting women’s equality are still alive today. The pandemic has highlighted that women still do most of the low-paying jobs in the service sector, many of which have now vanished. Few women are in trades and technology, which are recovering more quickly. Women still do most of the personal healthcare jobs that put them at higher risk of contracting the disease. There are still insufficient Day Care places; women stay home with their children when schools close and are still unable to return to work. In the Saturday, 25 July 2020 edition of the Vancouver Sun (p. NP5) a full-page ad reads “BC’s economic recovery depends on childcare.” What’s changed?

A few years ago I researched the Abortion Caravan and found it difficult to locate much verifiable information. It isn’t a well-known event, but this book will change that. Karin Wells’ The Abortion Caravan will be essential reading for all Canadian women. It will teach them, or remind them, of how hard women in the past worked to overcome barriers. It is a reminder that complacency is not an option — and that we still have a long way to go.

*

Donalda Reid is a retired elementary school teacher and Principal. She spends her time writing, taking photographs, painting and travelling. She’s married and lives in Vancouver. She’s a member of Federation of Canadian Artists. Her first book, Captive: A Survival Story, told how she survived her 1998 capture by Rwandan Hutus while in Africa to see mountain gorillas. Her second, The Way It Is, is a story of interracial friendship between two socially isolated teens set in 1960s Salmon Arm. Published by Second Story Press, it was nominated for the White Pine Award by the Ontario Library Association (Festival of Trees, 2012). Her 2019 book, Decision Point: an Impossible Choice, follows the main characters in The Way It Is. Editor’s note: Decision Point was reviewed by Zoe McKenna in The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster